Residential solar power shines on, backed by securitized lending

Residential solar is a small and rapidly expanding sector, with homeowners increasingly seeking cleaner energy sources and the ability to manage electric costs.

Residential solar is also in a sweet spot of sorts—offering generally high-performing solar systems with low environmental, social and corporate governance risk, and attracting high-credit-quality borrowers with little incentive to default.

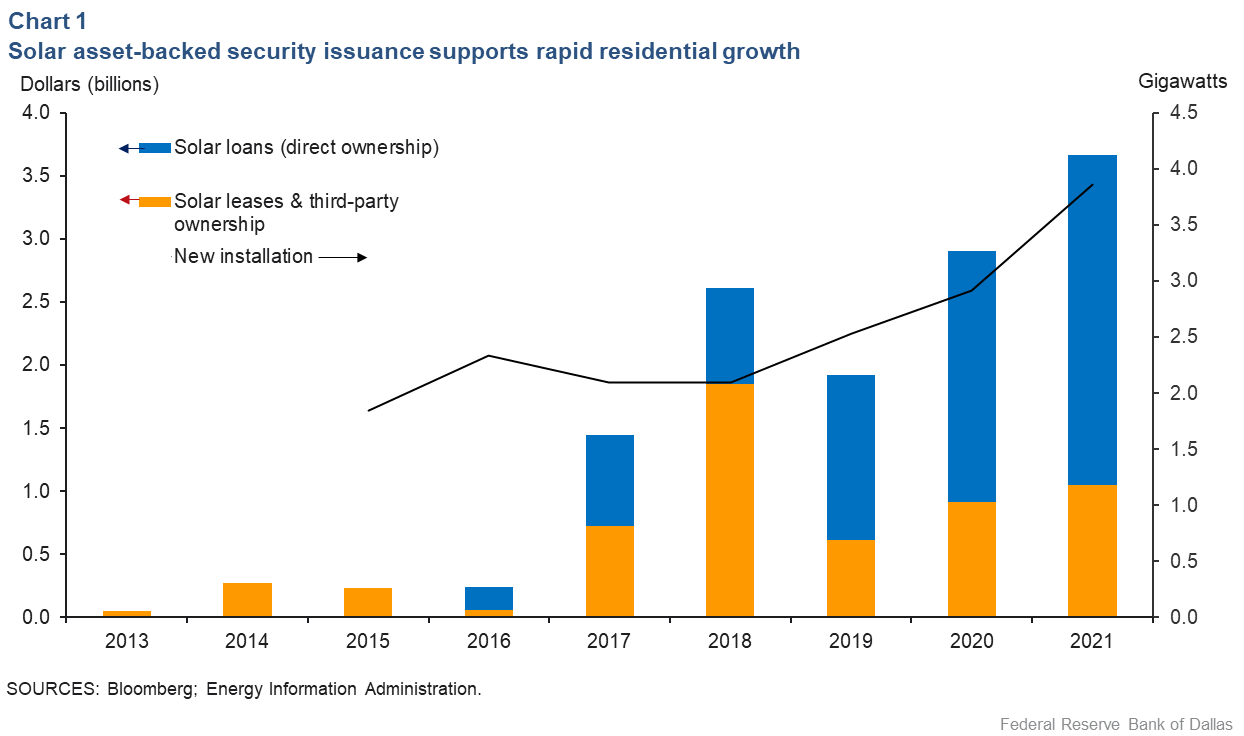

The securitization market—the packaging of loans to investors—has been one of the most popular sources of funding for new solar installations (Chart 1). Equipment lease payments, cash flow from power purchase agreements and loan repayment from home system owners stand behind solar-asset-backed securities, contributing to their rising popularity.

For example, Sunrun, a home solar, battery storage and energy services company, has installed 5 gigawatts of rooftop solar since its founding in 2007. The company has issued $2.6 billion of asset-backed securities, collateralizing about 1.8 gigawatts of aggregate generation capacity, according to Kroll Bond Rating Agency, which evaluates solar-backed securities at issuance. Approximately 41 percent of installations by Sunrun and its subsidiary, Vivint Solar, were securitized through solar-backed securities as of December 2021.

More direct ownership creates opportunities for banks

Before 2019, the residential solar market focused on third-party ownership. Retail customers obtained electricity generated from solar photovoltaic technology through a lease or power purchase agreement with third parties, usually developers. Banks largely provided credit to developers and their affiliates through a direct loan or via a syndicated loan, which spread the risk among a group of lenders or investors.

More recently, the residential solar market has shifted from third-party ownership to a direct-ownership model. Retail customers often install and own their solar systems, and loans cover equipment and installation costs.

Banks participate via loan-origination partnerships and whole loan purchases. For example, SunTrust Bank (now part of Truist Financial Corp.) entered a loan-origination partnership with solar power financier Solar Mosaic in November 2019. And Fifth Third Bancorp acquired Dividend Finance, which before the 2022 acquisition was in a strategic loan-origination partnership with KeyBank.

Residential solar loans pose unique credit-risk considerations

Banks carrying solar loans or solar loan securities on their balance sheet assume unique risks. For example, solar module manufacturing is concentrated among a handful of suppliers—the top 10 account for 77 percent of global solar panel production, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, an affiliate of the Energy Department. As a result, lenders may have concentrated exposure within their solar portfolios to warranties for equipment and workmanship defects from a handful of companies.

State regulatory changes can also affect the credit profile of a solar loan. For example, a California Public Utilities Commission plan recently reduced the value of future residential solar systems by limiting net metering, under which residential solar system owners can sell unused electricity to operators of the power grid.

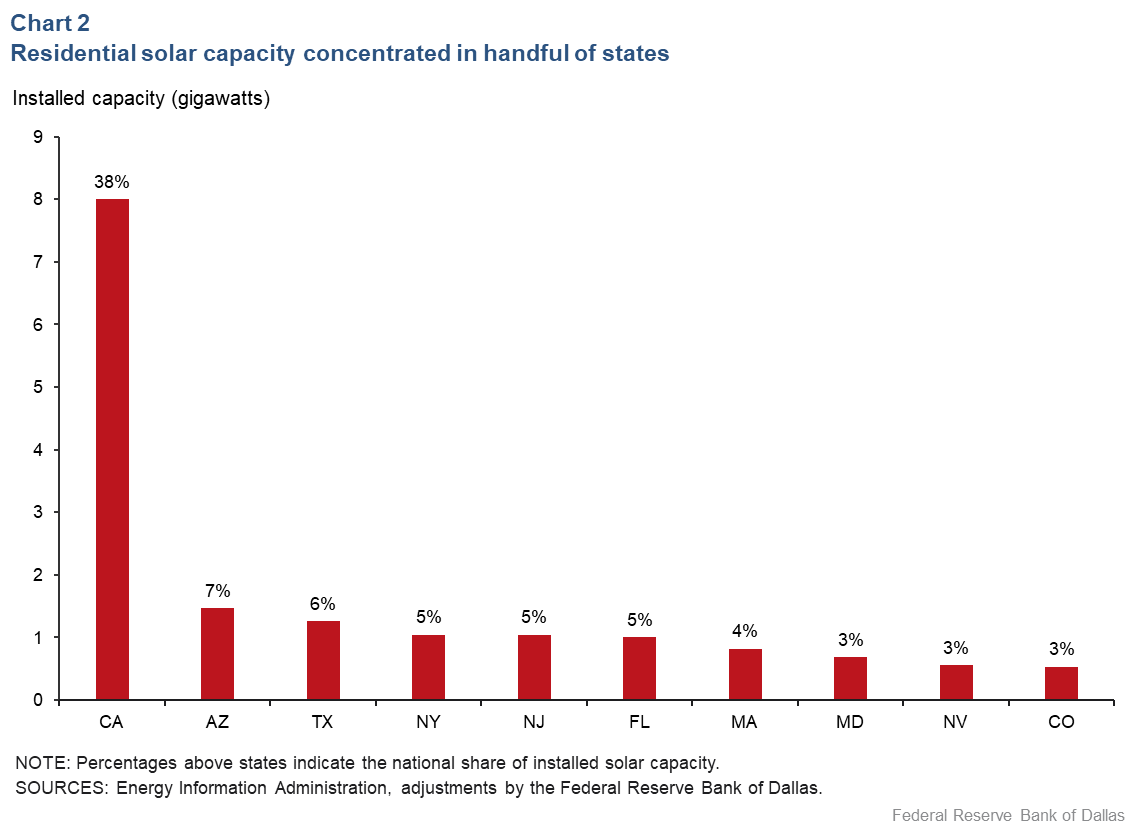

Geographic concentration of loans among a relative handful of states is another major risk consideration for residential solar financiers (Chart 2).

Weak geographic diversification increases risk exposure resulting from a sudden change in state regulation—for example, involving net metering—and from a regionalized economic downturn or natural disaster. Hannon Armstrong, an investment firm active in climate-related enterprises, acknowledged in its 2021 filing to shareholders that it faces potential resource risk due to climate change and regulation risk for its investments in residential solar.

Historically strong credit performance

The residential solar sector’s performance is stable, with low delinquency rates. Based on historical cumulative loss data, residential solar asset-backed securities show relatively strong credit performance during periods of heightened macroeconomic stress. However, more recently established companies have not experienced a full credit cycle.

Most residential solar systems were installed over the past decade—the first solar-based securities were issued in 2013. Risks to financiers continue to evolve as both the product and financing arrangements change.

Today, auxiliary products (power storage, electric vehicle connections) along with some nonsolar products (storm windows, heating and air conditioning) are bundled into residential solar loan packages or are part of home-improvement financing arrangements.

The added features, combined with higher equipment and labor costs for installation, have increased solar loan amounts on average and contributed to lengthening loan maturities. Furthermore, these added features could affect the collateralization of solar loans because some of the added features— especially those for home-energy-efficiency purposes—may not be “detachable,” leaving a lender without a way to reclaim assets due to loan default under the federal Uniform Commercial Code.

While posing new financial challenges, residential solar remains a small, yet rapidly expanding sector. The recent shift toward direct ownership of residential solar provides opportunities for financial institutions to enter the marketplace and extend credit. While historical credit data indicate strong sector performance, financial institutions must acknowledge and address potential risks associated with evolving financing terms and unique sector characteristics.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System.