Texas economy mends in fits and starts from pandemic’s onslaught

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about the steepest and fastest drop in Texas economic activity in modern history. Measuring this decline in real time proved very difficult, as the pace of change in response to the pandemic shifted on a weekly and sometimes daily basis.

Real-time data from the Texas Business Outlook Surveys (TBOS), combined with other high-frequency measurements, have helped provide a timely and comprehensive look at the scale of impacts to the state economy during the first half of the year. In light of the surge in COVID-19 cases in June and July, these indicators have helped inform an outlook for the second half of the year; they suggest the state likely won’t regain its prepandemic strength by year-end.

Eclipsing the Great Recession

Heading into 2020, Texas employment expanded slightly below its long-term pace of 2.0 percent, in part due to softness in the energy and manufacturing sectors. Nevertheless, the state faced its tightest labor market in decades, with unemployment rates bottoming out at a historically low 3.5 percent. Business activity remained steady in the service sector and was beginning to improve in manufacturing at the start of 2020.

There was little sense that a decline of the scale and speed brought on by COVID-19 was about to hit.

As the virus took hold in Texas in early March, businesses rapidly pulled back to slow its spread. Many municipalities issued shelter-in-place orders, and these were subsequently extended statewide April 2. Economic activity plunged in the second half of March and into April, and businesses designated as nonessential closed or reduced operations. Others experienced evaporating demand as customers stayed at home.

Adding to the impact in Texas, energy exploration and production collapsed, diminishing significant shares of state exports and output. Notably, near-term West Texas Intermediate futures briefly traded at negative prices on April 20; producers paid buyers to take their oil amid concerns that a glut would leave no place to store supplies.

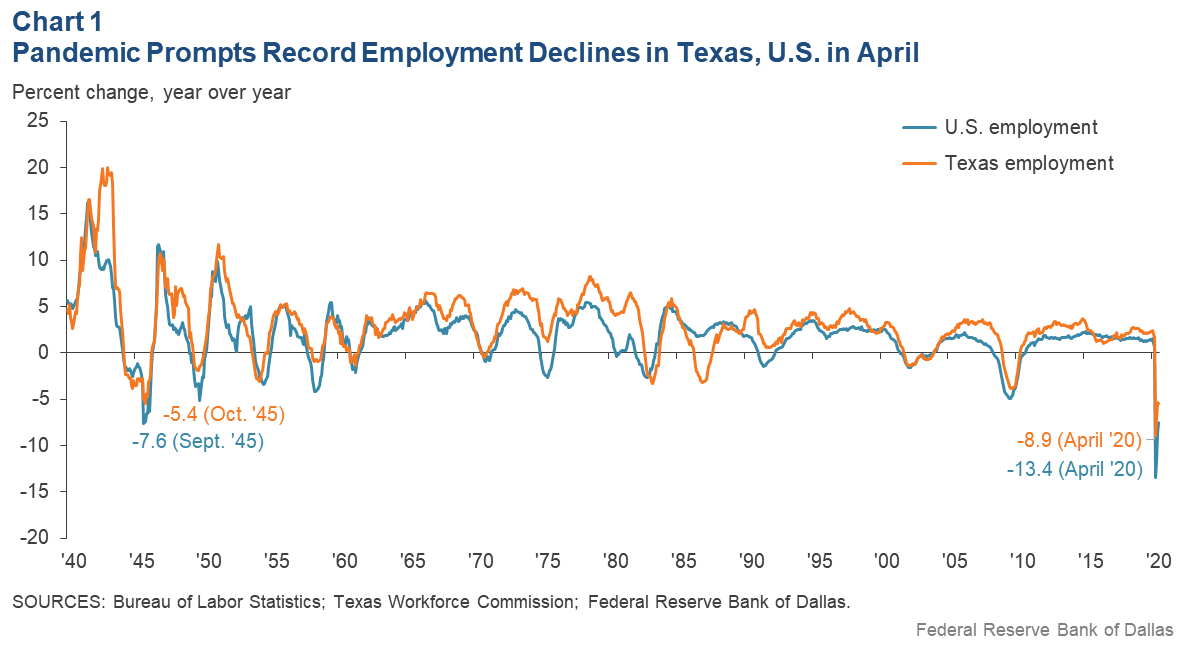

The wide-ranging economic collapse in Texas came as the nation experienced an even broader and steeper decline. The state and the U.S. observed the greatest economic fall-off since as far back as data are available (Chart 1). On a year-over-year basis, employment in Texas fell almost 9.0 percent in April, with the previous steepest monthly drop being a 5.4 percent decline following the end of World War II. The nationwide employment decline was even more pronounced, -13.4 percent in April.

As a result, the Texas jobless rate surged to a record high of 13.5 percent in April.

Confounding Typical Forecasting

In the midst of the pandemic, tracking the Texas economy’s decline in real time, along with estimating a recovery, became even more difficult due to the lagged timing of the indicators typically used to monitor regional growth. The full depth of the decline in April was unknown until late May. By then, some businesses had begun reopening, and a nascent recovery had begun.

The Texas Leading Index (TXLI), an indicator the Dallas Fed uses to forecast job growth over the upcoming 12 months, proved too slow to catch the rapid shut-in of activity from February to April.

Previously, during the Great Recession, the TXLI peaked a full year before the beginning of the economic downturn in Texas, while in the prior three recessions, the TXLI peaked five to 15 months before the onset of a recession.

However, the TXLI provided no forewarning of the 2020 downturn, and by the time it registered a drop of any significance, the economy was already in freefall. Similarly, as the index began to increase in May—with data released in June—a recovery was already underway.

TBOS Captures the Decline

As the impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak spread across the state economy, TBOS not only provided a more rapid, real-time picture of the decline but also helped capture its scope. The service sector survey, along with its subcomponent retail outlook survey, reported unprecedented declines across almost all indicators in March and April, plunging to levels well below those experienced during the depths of the Great Recession.

The manufacturing survey, while also registering steep declines, did not weaken to the same extent. Typically, downturns in the business cycle are led by cyclically sensitive industries in manufacturing, but the relative performance of this sector provided an early sign that the compositional impact of the COVID-19 recession would be unlike past downturns. Declines steepened in April across the surveys—particularly in manufacturing—pointing to a widening negative impact that would ultimately touch every industry.

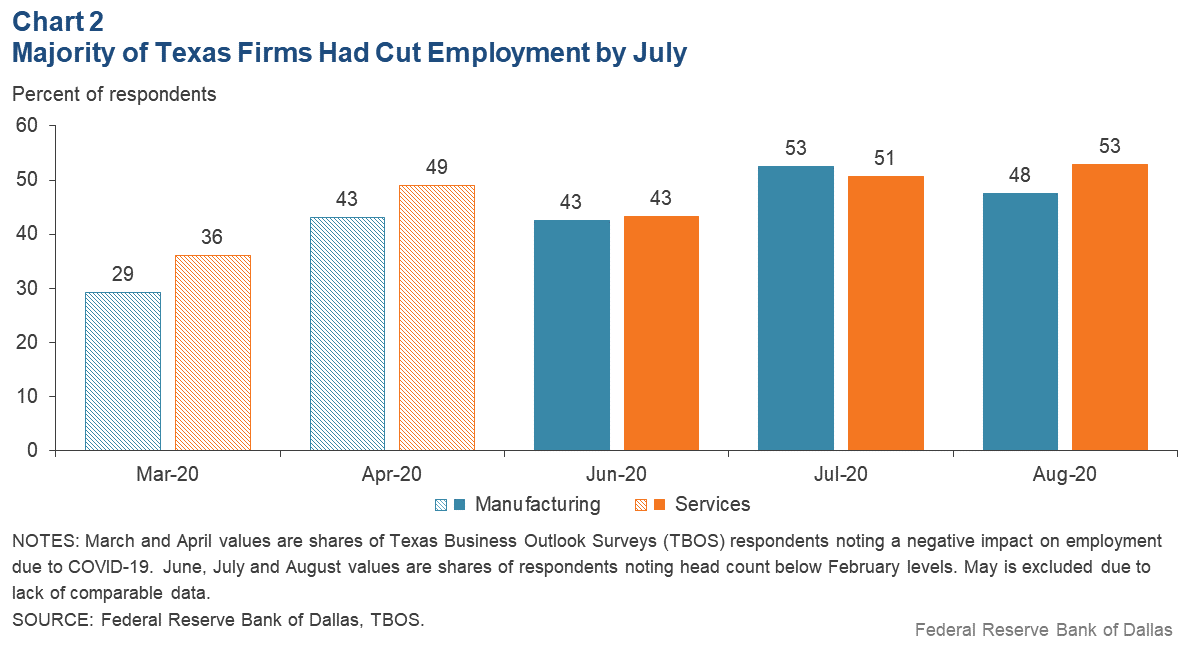

TBOS special questions also provided an early sense of how many firms were furloughing and laying off workers. Between March and April, the share of firms noting falling employment due to COVID-19 rose nearly 15 percentage points in manufacturing and services, with about half of services firms reporting employment reductions by April (Chart 2).

Further highlighting the disparity among industries, only 24 percent of manufacturers expected not to rehire those employees taken off payrolls; for services, the share exceeded 50 percent.

By May, signals emerged that the economy had hit a bottom. While the TBOS survey headline indexes of production and revenue remained in contractionary territory, they pointed to a much slower pace of decline than the prior two months. An unambiguous resumption of growth appeared in June, as both the manufacturing and service sector survey headline indexes rebounded to positive territory. Similarly, the shares of firms reporting layoffs had plateaued, suggesting that the worst of the economic impacts from the crisis had likely passed.

Unprecedented Policy Response

Quick and broad fiscal support to firms and individuals during the depths of the crisis contributed to the economic upturn after the initial plunge. The federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), which targeted firms with fewer than 500 employees, figured prominently. The program distributed loans of up to 2.5 times a firm’s average monthly payroll costs. The loans were forgivable if the recipient maintained or restored its February-level head count and did not cut employee salaries by more than 25 percent.[1]

Individuals benefited from government stimulus checks distributed in April. Additionally, pandemic unemployment benefits that supplemented state benefits with an additional $600 weekly federal payment provided support to a broad base of recipients. This included many self-employed and “gig economy” workers not typically covered by state unemployment programs.

Data from the May TBOS surveys show widespread PPP participation among Texas firms, with about 60 percent reporting seeking a loan and more than 90 percent of those applicants receiving funding.

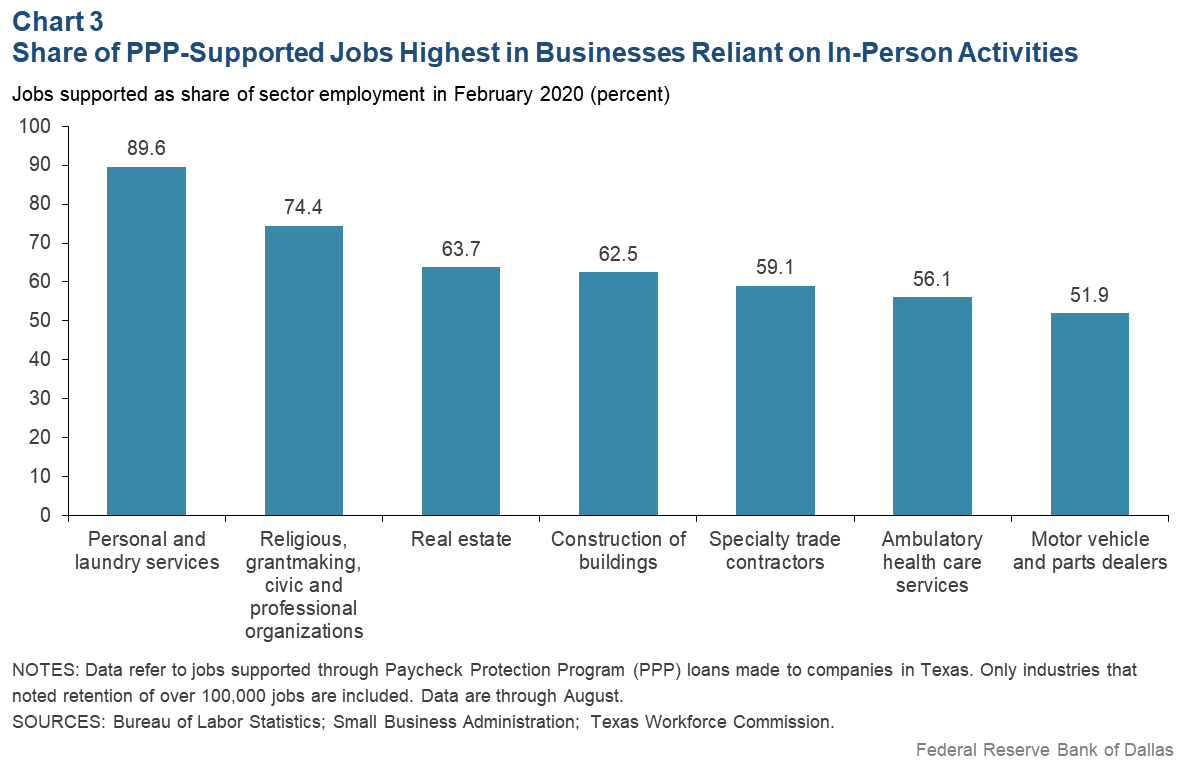

More than 75 percent of firms that obtained a loan said the funds helped them prevent furloughs and layoffs, and two-thirds reported that it helped prevent wage reductions. Broader data from the Small Business Administration confirmed the PPP loans’ usefulness, as over 400,000 firms—nearly 60 percent of all private establishments in Texas—received a loan of some kind. These firms, taken together, account for about 34 percent of state employment.

PPP uptake was not uniform across industries, however. Looking at employment among firms supported by PPP loans as of early August, lending was particularly notable in seven industries in which at least half of employment was supported by PPP. Recipient firms largely operated in personal-care services, civic and religious work, real estate and construction (Chart 3).

Industries requiring a high degree of human contact or with a low share of employee ability to work from home were more likely to have taken PPP funds. Recipients were most prevalent in the restaurant and bar industry, accounting for more than 560,000 Texas jobs. While it is unclear how many layoffs would have occurred absent PPP, additional comments from TBOS suggest that a great many firms retained employees that they otherwise may have dismissed.

At the same time, a number of firms suggested that they could not stay afloat without rapidly improving demand because PPP loans offered only short-term relief. These companies indicated they would be forced to implement layoffs once the PPP forgiveness period expired.

Thus, the support from the PPP appears somewhat fragile among some sectors—such as the hard-hit restaurants and personal-care services—which are less likely to maintain staffing beyond the forgiveness period. Others, such as construction, real estate and professional services have largely regained their footing and retained employees.

Recovery Wanes in July

The apparent turnaround in June gave way to a more mixed economic picture in July, as COVID-19 cases surged across the state. TBOS data indicated manufacturing gains continued, as production and forward-looking indicators, such as new orders, accelerated.

The service sector, on the other hand, experienced renewed contraction in July. Authorities ordered some businesses to close, such as bars, though there wasn’t a repeat of the broader lockdowns instituted in March and April. A mask mandate implemented to slow viral spread helped lower the rate of infection from its peak in July. Consumers appeared to retrench somewhat as the Dallas Fed’s Mobility and Engagement Index declined from a relative high in late June. COVID-19 deaths, which had been largely steady between April to June, began rising sharply in mid-July.

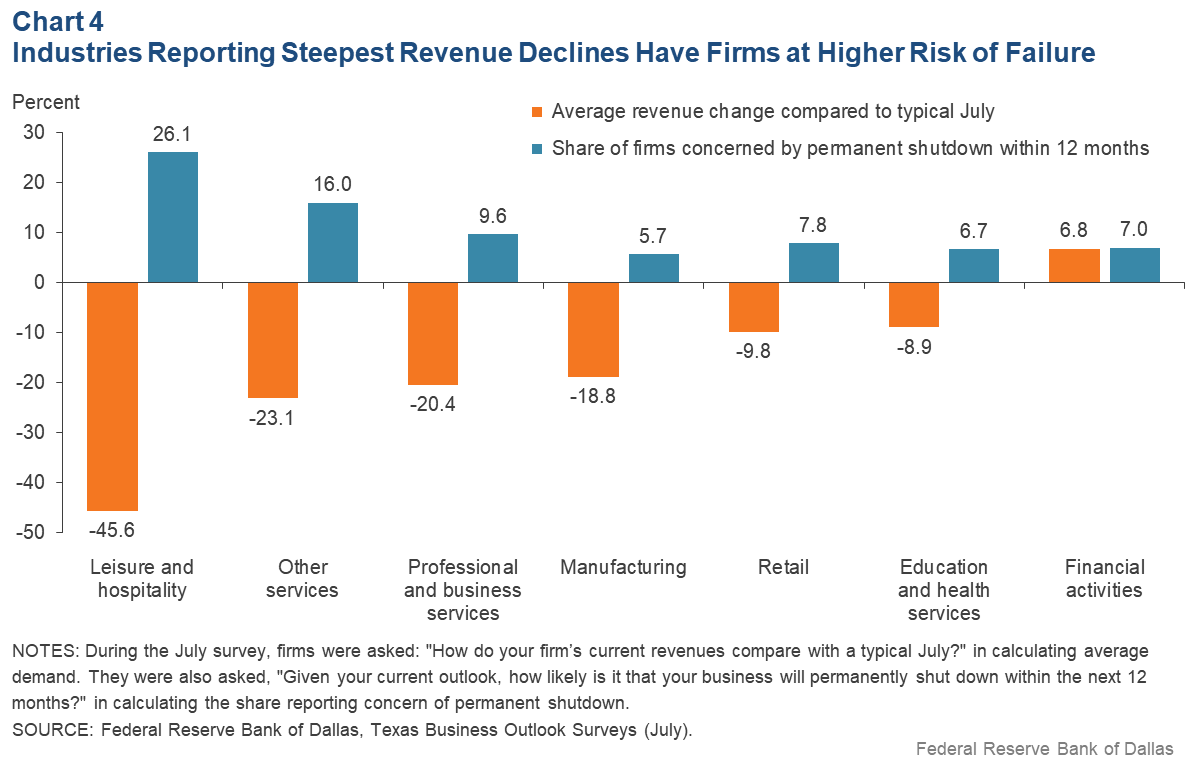

TBOS special questions in July highlighted particular weakness in sectors relying on face-to-face contact. These same sectors previously signaled recovery as consumer mobility had started increasing. Most notable were respondents engaged in leisure and hospitality, which includes restaurants and hotels, as well as other labor-intensive industries. They reported revenue declined almost 50 percent during July relative to a typical July (Chart 4). Other services, such as personal care and civic organizations, noted a nearly 25 percent revenue decline.

These highly impacted industries were similarly pessimistic when asked to gauge their likelihood of permanently shutting down over the coming year. More than one-quarter of leisure and hospitality firms reported a “somewhat” or “very” likely possibility of permanently closing within the next 12 months given their current outlook.[2]

That could change with an improvement in the public health situation and a broad-based state-sanctioned reopening of businesses such as restaurants, bars and other high-contact services. However, with the unpredictability of the virus’ spread, it is unclear whether a resumption in activity will occur soon enough to keep firms from failing.

Economic uncertainty in the second half of the year remains heightened due to a number of factors beyond the direct effects of the virus. A reduction or elimination of many of the largest federal stimulus programs looms as a potential short-term headwind.

High-Frequency Measures

With the myriad changes buffeting the regional economy since January, traditional measures of activity provide little clarity on how things will look at year-end. However, high-frequency indicators provide clues regarding what is in store in the near term and help guide forecasting.

The Dallas Fed’s Texas Weekly Employment Estimate (TWEE) is an aggregation of six data sources shown to be reliable indicators of economic activity, particularly during the recent downturn.[3]

In line with TBOS indicators and official employment data, the TWEE signaled a decline in July as mobility decreased and business reopenings were rolled back. By August, the weekly measure along with other high-frequency indicators suggested that while COVID-19 case growth remained elevated, its impact had slowed notably from the July peak, helping provide some economic momentum heading into the fall (see Snapshot in this issue).

Incorporating the recent improvements in TWEE readings into a modified employment forecast suggests that growth through the end of the year will be over 3 percent—well above the state’s long-term average of 2 percent. Nevertheless, given the earlier slump, this would leave the level of employment at year-end nearly 5 percent below the December 2019 reading and more than 600,000 jobs short of the pre-COVID-19 peak.

Risks to the Outlook

Economic uncertainty in the second half of the year remains heightened due to a number of factors beyond the direct effects of the virus. A reduction or elimination of many of the largest federal stimulus programs looms as a potential short-term headwind. On the consumer side, mixed prospects for the federal unemployment subsidy threaten to curtail otherwise robust spending that has continued to sustain revenues for many firms during the pandemic.

For businesses, the winding down of the spring PPP effort is likely to force many to look more closely at cutting expenditures, particularly those related to labor costs and real estate leases.

An additional issue that remains very fluid is the state of schools, particularly elementary schools, in the coming academic year.

Many large school districts started predominantly online. With the infection rate still elevated in Texas, lack of full in-person learning is likely to hamper a return to work for some of the 33 percent of households participating in the labor force and that have a grade-school child at home.

Longer term, the impacts of reduced collections of sales taxes, oil and gas severance taxes, hotel occupancy taxes and other revenue sources have left significant gaps in state and many municipal budgets. Already, the number of state and local government jobs has declined more than 5 percent since February. This shortfall is likely to continue to be a drag on growth in many large cities and the state as a whole.

Notes

- For more information, see “Small Business Hardships Highlight Relationship with Lenders in COVID-19 Era” by Wenhua Di, Nathaniel Pattison and Chloe Smith, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Second Quarter 2020.

- For more information, see “Insights from Dallas Fed Surveys: Uneven Economic Recovery Likely in Texas,” by Emily Kerr and Christopher Slijk, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Dallas Fed Economics, Aug. 11, 2020.

- For more information, see “Texas Weekly Employment Estimate Provides New, Early Economic Insights,” by Jesus Cañas, Keith R. Phillips and Carlee Crocker, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Dallas Fed Economics, Aug. 18, 2020.

About the Author

Christopher Slijk

Slijk is an associate economist in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2020/swe2003.