Innovation promises efficiencies in remittances, if regulation can keep up

Remittances, or personal money transfers by individuals abroad, are vital to the Mexican economy. In 2024, Mexico received $64.7 billion in total remittances (roughly 3.7 percent of Mexico’s GDP), most of which came from the United States. These remittances are a valuable lifeline for millions of households in Mexico, especially in the poorest states.

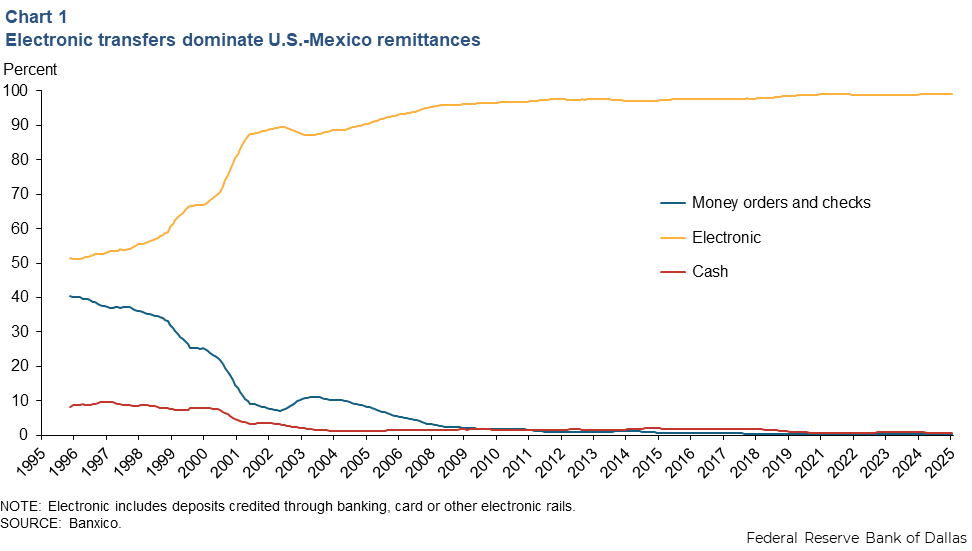

Today nearly all remittances travel over electronic payment rails rather than via the physical transportation of cash (Chart 1). Yet the business models underlying these payments differ sharply in cost, speed, accessibility and compliance overhead. Costs, access to financial services and advancements in payments technologies have led to shifts from once-dominant banks and money transfer operators (MTOs) to digital platforms and crypto exchanges. As payments technologies evolve faster than the rules governing them, understanding both the mechanics and policy trade-offs of cross-border transfers is increasingly important.

International remittance transfer cost varies widely

The traditional process of transferring money internationally is complicated, often involving payment card networks, such as Visa or MasterCard, or a chain of bank-to-bank transactions. And every cross-border transfer straddles at least two rulebooks, with the gaps between those systems creating operational frictions.

The sending and receiving pair of countries in a remittance transaction is called a “corridor.” Each intermediary in a corridor must meet requirements for data security, consumer protection and financial crime prevention, and the associated costs are embedded in the overall transfer fees.

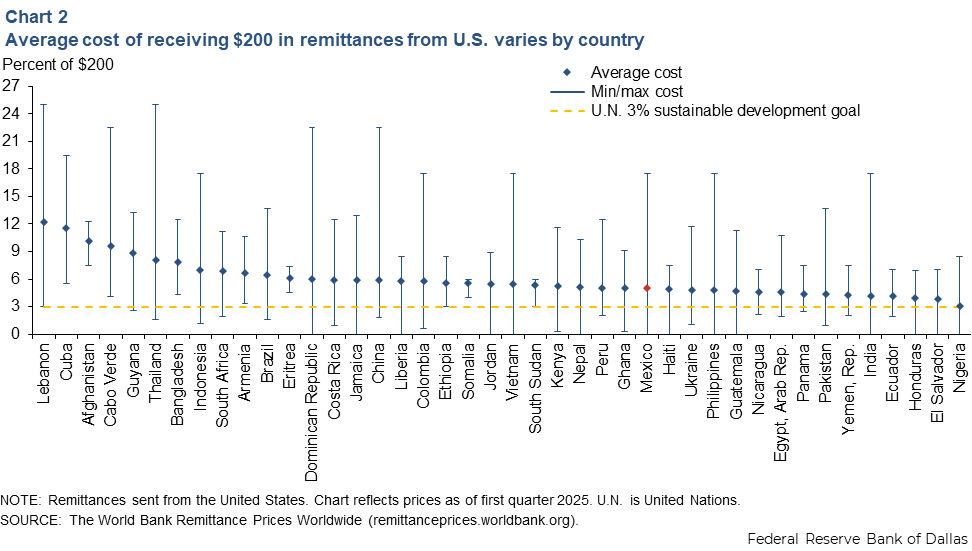

In the U.S.-Mexico corridor, the average fee is slightly below 5 percent of the value of the remittance for a $200 transfer, based on our analysis of first quarter 2025 World Bank data. While this cost is lower than in other equivalent corridors, it is still somewhat above the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal of average remittance fees below 3 percent by 2030. The U. N. has recommended a series of actions to help meet that goal, including:

- Encouraging remittance service providers to adopt competitive business models and invest in more cost-effective distribution channels; and

- Urging governments to support predictable enabling environments for innovators such as fintech, mobile network operators and nonbank financial institutions.

Research suggests remittance flows are sensitive to transaction costs; remitters tend to send less money when transaction fees are high. The U.N. and the World Bank estimate that a reduction to 3 percent in average transaction costs would result in $20 billion in annual savings for consumers.

The cost of sending remittances varies widely due to a host of factors such as the local regulatory environment; the degree of competition among providers serving the corridor; and the availability of financial infrastructure. Costs can also vary widely within countries. Fees are usually paid by senders, but receivers may also pay additional fees in some cases. Individual providers’ fees in Mexico range from zero to well above 10 percent (Chart 2).

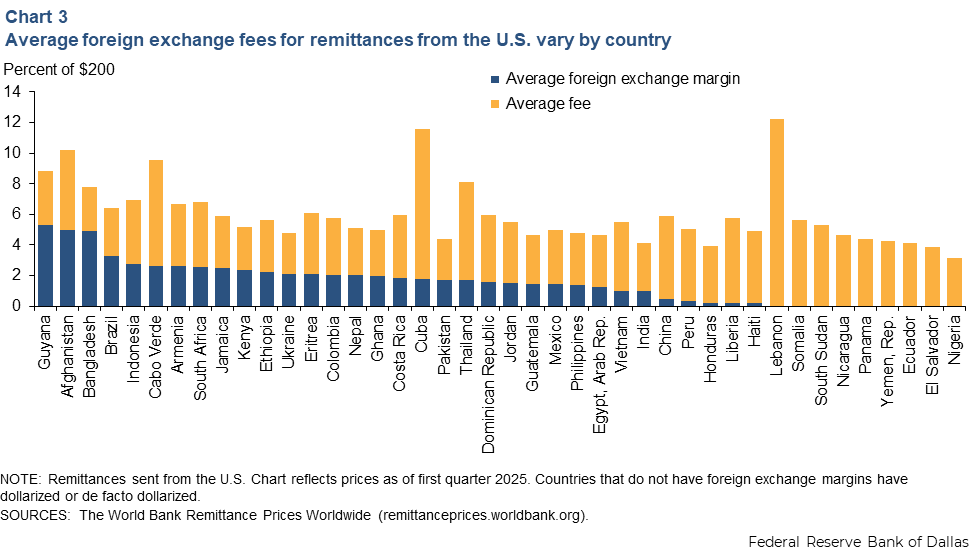

That wide range reflects both explicit and hidden fees, which make it difficult for consumers to compare service providers’ pricing. The biggest driver of hidden costs appears to be exchange rate conversions, according Washington-based think tank Inter-American Dialogue (Chart 3).

In addition, outbound remittance taxes imposed by some countries, while rare, could also add meaningful costs. For example, beginning next year, the U.S. will charge a 1 percent federal excise tax on certain outbound remittance transfers as part of the newly enacted One Big Beautiful Bill Act. The tax applies primarily to cash-based transactions using money orders or similar instruments.

Remittance models shift

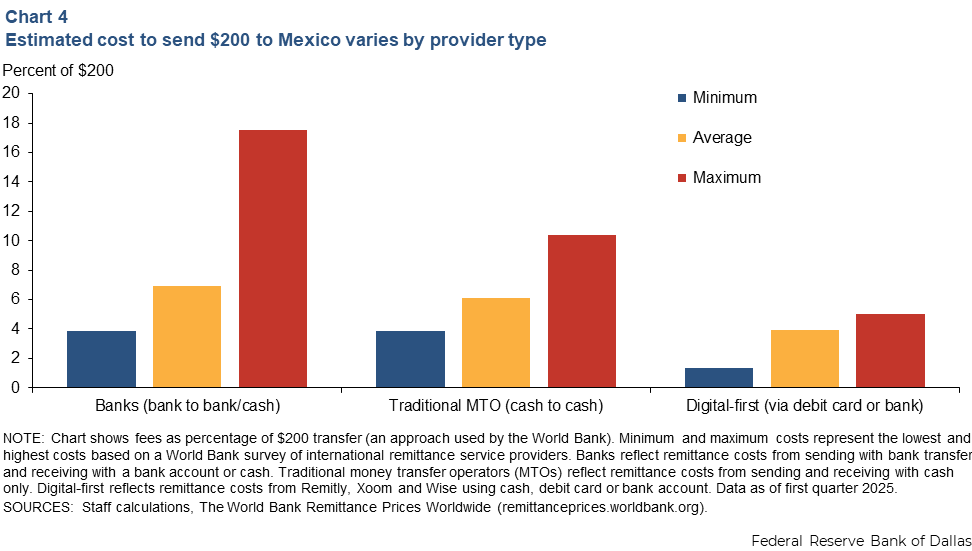

Traditionally, money transfer operators (MTOs) and banks have dominated the remittances business in the U.S. Cash-oriented MTOs rely on extensive brick-and-mortar agent networks. They remain popular among senders or receivers who are unbanked or prefer cash despite high total charges that average 4 percent to 10 percent of a $200 transfer (Chart 4). Traditional MTO prefunded bank accounts in destination countries enable quick transfers. Even without bank accounts, recipients can collect funds on the same day, but at the cost of potentially high fees.

Banks offer international transfers (typically wire transfers) and charge high flat fees, plus foreign exchange conversion spreads. These transfers rely on correspondent banking networks, with several intermediaries often involved in transfers. Bank transfers are often the most expensive option, typically costing 4 percent to 18 percent of a $200 transfer. Despite being slower (usually one to five business days), banks remain an important channel for business-to-business payments and large transfers due to built-in regulatory compliance and capacity to handle higher volumes securely.

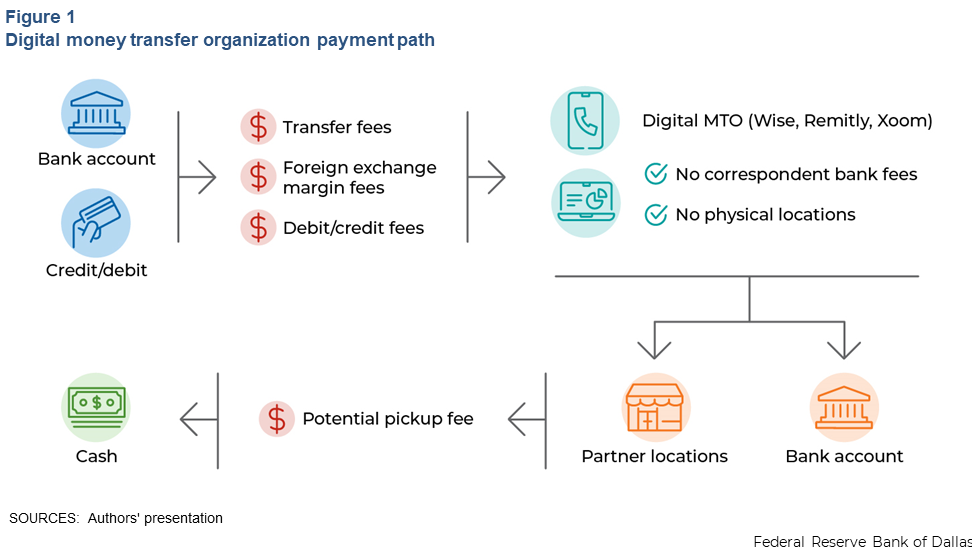

Over the past decade, digital-first MTOs such as Remitly and Xoom have created a lower-cost model as they bypass much of the traditional remittance infrastructure. They operate predominantly through internet or mobile channels instead of brick-and-mortar agents, although many also offer cash pickups via partners at higher fees. While traditional MTOs and banks typically rely on correspondent banking networks to move money, digital MTOs often have prefunded accounts in senders’ and recipients’ countries. The MTO nets out cross-border payments traveling through these accounts. Digital MTOs avoid correspondent banking fees and deliver funds in seconds when payment card networks are used, or on the same day using the Automated Clearing House, an electronic retail payment system (Figure 1).

Push-payment services, namely Visa Direct and Mastercard Move, provide the backbone for many digital-first MTO apps. These services typically send funds by pushing payments through the card networks to end customers, often reducing processing time. Card network fees can serve as minimum prices for transfers, and the networks often include features that can help companies more easily meet compliance requirements.

Digital-first MTO transfers cost less than bank wires and traditional MTO transfers, around 2 percent to 5 percent of a $200 transfer. The trade-off is access. Digital access or mobile banking is often required to take advantage of some of digital MTO services’ accessibility and cost-saving features. Research shows that in Mexico, only 27.5 million adults—roughly 30 percent of the adult population—have used mobile banking.

Even so, market-share data estimated by Inter-American Dialogue underscore just how quickly competitive dynamics are shifting in the U.S.-Latin America corridor. Remitly, a digital-first app that launched just a decade ago, has vaulted from 14 percent of the U.S.-Latin America and the Caribbean volume in 2020 to almost 23 percent in 2024, overtaking Western Union for the top spot (Table 1). Over the same period, Western Union’s share has fallen by half as more senders migrate from cash agents to digital channels. The biggest contraction is in the fragmented “other” category, which suggests volume is concentrating in a handful of larger platforms. Taken together, the figures suggest a tilt toward digital services even as traditional MTOs continue to move a significant share of the corridor’s flows.

| Money transfer operators | Firm type | 2020 (percent) |

2023 (percent) |

2024 (percent) |

| Remitly | Digital | 14.0 | 18.9 | 22.7 |

| Western Union | Traditional | 29.0 | 17.9 | 16.8 |

| Intermex | Traditional | 13.0 | 15.9 | 15.7 |

| RIA | Traditional | 7.0 | 12.0 | 11.6 |

| MoneyGram | Traditional | 7.0 | 11.4 | 9.9 |

| Viamericas | Traditional | 5.0 | 8.6 | 9.7 |

| Paypal/Xoom | Digital | 6.0 | 6.0 | |

| Dolfintech | Traditional | 5.6 | 5.7 | |

| Others (Worldremit, FelixPago, MaxiTransfers, etc.) | 24.0 | 10.6 | 11.0 | |

| SOURCE: The Inter-American Dialogue | ||||

Crypto disruptors offer promise but have limitations

More recently, crypto-based services have emerged, promising even lower costs by converting dollars to cryptocurrency and transmitting the token via borderless public blockchains. The funds remain in cryptocurrency in the recipient’s wallet until the token is sold on the corresponding exchange or cashed out for local currency at a partner outlet. Blockchain transfers appear to be gaining adoption due to cost- and time-saving advantages. Bitso, a large crypto exchange in the U.S.-Mexico corridor, claims it processed over $6.5 billion in remittances in 2024—more than 10 percent of the total volume between the two countries.

Estimating the cost of sending money abroad via blockchain is difficult. The cost can vary significantly depending on several factors, chiefly the on-chain transfer or gas fees charged by blockchain networks and the on- and off-ramp fees charged by these networks and other intermediaries.

While the on-chain transfer fee is usually minimal, it depends on the network and can fluctuate based on network activity. On- and off-ramping refers to the transfer of currency into and out of the crypto ecosystem, which occurs over traditional payment infrastructures. In addition, the total cost of blockchain transfers is influenced by market volatility related to exchange rates and cryptocurrency prices, which fluctuate wildly. Stablecoins, cryptocurrencies with values pegged to real-world assets (often the U.S. dollar) can help mitigate price volatility associated with cryptocurrency conversion. But the transfer remains subject to the other fees.

With blockchain transfers, an important structural change in remittance payments emerges: such transfers unbundle currency conversion from the cross-border transfers themselves. In traditional models, the transfer and the currency conversion happen at the same point, usually controlled by a single intermediary such as a global bank or a card network. With blockchain transfers, senders can choose where to exchange U.S. dollars to cryptocurrency and which network to transfer on. Recipients can choose when and where to convert their digital assets to local currency. That flexibility introduces competition in all layers, potentially driving down overall costs.

Sending money via blockchain requires a certain amount of digital and financial literacy. But services offered by crypto-native platforms may increase accessibility by simplifying this process into a single, app-based smart phone flow.

Estimating the adoption scale of crypto-based transfers is challenging due to the blurring of lines between traditional, digital-first and crypto-native MTOs. Many traditional players have explored or adopted blockchain technologies. For example, PayPal, the parent company of Xoom, has launched a dollar-denominated stablecoin called PYUSD, and MoneyGram offers digital wallets for sending and receiving cryptocurrency.

Compliance is crucial in digital corridors

Payment technology is racing ahead of the rules that keep remittances safe. Banks and cash-based MTOs and most app-driven MTOs already operate inside well-tested U.S. and Mexican Anti-Money Laundering/Know Your Customer regulatory regimes. Crypto-native services, by contrast, sit at the regulatory frontier. But the gap appears to be closing.

One catalyst is the June 2025 expansion of the Travel Rule. The rule, administered by the Financial Action Task Force, requires companies to collect originator and beneficiary data (addresses, dates of birth and account identifiers) for all cross-border payments, including virtual-asset transfers. To be compliant, blockchain-based remittance firms must now build secure messaging layers onto publicly visible networks originally designed to move codes and values, not private, personally identifiable information.

Domestic legislation is also catching up. The GENIUS Act, signed into law in July, brings U.S. issuers of dollar-backed stablecoin under the purview of federal regulators, requiring monthly reserve attestations and government oversight. Wallets that rely on regulated stablecoins will become the issuers’ critical front end that onboards customers and collects relevant data for compliance screening, narrowing the regulatory gap that once enabled lower operational costs.

A payment that clears U.S. anti-money-laundering screens must still satisfy Mexico’s identity and record-keeping rules, which may rely on different documents and data formats. Real-time rails make those rulebook gaps more visible—and more expensive—because screening now happens in real time with near-instant transfers. Each new data field, audit requirement and account review may add operational cost and delay. The open question is whether crypto-based remittances, celebrated today for speed and cost, will retain those advantages once they fully absorb the same compliance architecture that governs banks and MTOs.

About the authors