Network structure of money markets and firms affects policy transmission

Most advanced economy central banks before the Global Financial Crisis (2007–08) used scarce reserves frameworks under which policy rates were highly sensitive to reserve supply. A central bank could achieve a specific target rate by adjusting the reserve supply.

In the ample reserves framework now used in the United States, interest rate sensitivity to reserve supply is moderate, limiting the practicality of rate control via reserve supply. Instead, target rates are primarily controlled through administered rates, which offer outside lending and borrowing options to certain market participants.

Banks provide liquidity and maturity transformation, an essential function of the financial system. Central to this function is the management of liquidity balances, most importantly reserves. They are claims on the central bank that allow banks to settle interbank obligations. Money markets, which allow both banks and their nonbank clients to rebalance their liquidity, are essential to liquidity management. Money markets and the types of firms that participate in them are heterogeneous and form a complex network. Changes in policy instruments—such as the supply of reserves or administered rates that touch on one part of the network—ripple outward through the rest of the network.

While reserves can be traded directly (as in the federal funds market), most liquidity management transactions that give rise to reserve reallocation between banks occur in other money markets. Liquidity management can be highly complex, depending on the structure of a bank’s liabilities, the transaction flow of its deposit customers and the liquidity of its assets.

Bank treasurers rely on a variety of money markets for short-term liquidity management, including brokered deposits, commercial paper, Federal Home Loan Bank advances, federal funds, Eurodollars and selected deposits, and repurchase agreements (repo). Banks may also choose to rely on liquidity provided by the official sector, such as primary credit at the Fed discount window, which can be priced competitively with certain market segments and is intended to provide healthy banks with adequate liquidity in support of monetary policy transmission. Additionally, banks manage their liquid assets to adjust their liquidity positions, implicitly relying on market provision of liquidity, though this is outside the scope of this discussion.

It is instructive to view the various money markets from the perspective of a bank treasurer. Domestic banks generally rely on long-lived, stable deposits from households and nonfinancial businesses. But it is often not optimal to hold a liquidity buffer against all possible demands, and customer deposits are impractical and expensive to source on short notice.

A treasurer’s choice of liquidity source is determined by price, tenor (or term), settlement timing, market access and operational capacity. Differences in market access and operational capacity between large and small banks drive significant differences in the sources banks tap. Among foreign banks, restrictions on their ability to hold retail deposits in the U.S. (and elsewhere) steer them toward a different mix of liquidity sources than their domestic counterparts.

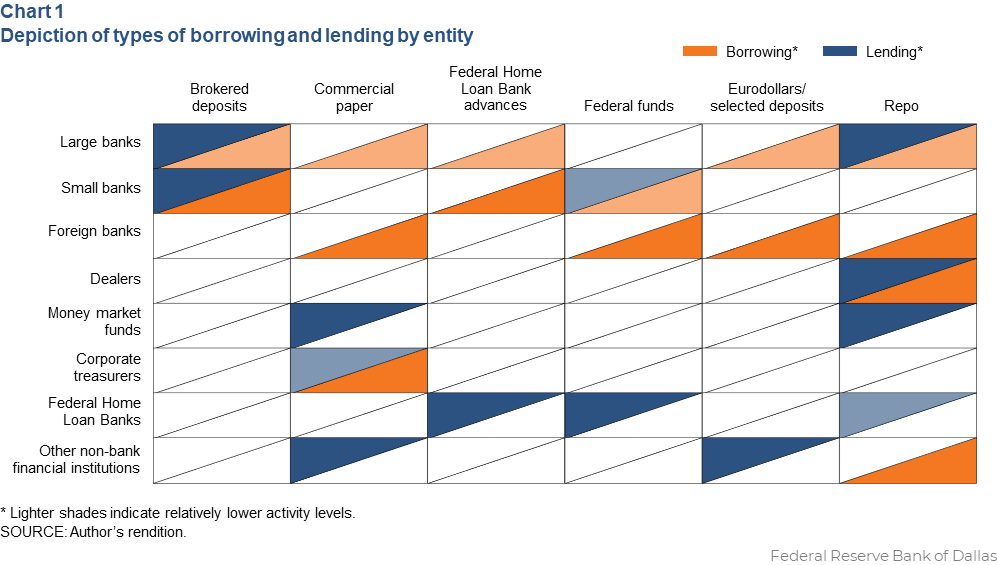

As a result, different types of financial institutions are active in different money markets. Entities include U.S. and foreign depositories of various sizes, dealers, money market funds, corporate treasurers, Federal Home Loan Banks and other nonbank financial institutions. The relationship between rates in different markets is thus determined by cross-product elasticities, a result of firms substituting between the various markets in which they borrow or lend, and arbitrage (firms simultaneously borrowing in one market and lending in another). One can think of the activity of different types of entities in different markets as a bipartite, directional graph, with this network represented as a matrix (Chart 1).

The relationships between these money markets are both complex and important to monetary policy transmission. The links between various money markets are frequently indirect. As a result, when outside factors lead to increased supply or demand for borrowing in one market, the effects can cascade through the network unevenly, changing the relative borrowing costs between other pairs of markets. The relationships between markets also change as market structure evolves. Thus, the strength of the relationship between funding rates in different markets can vary significantly over time.

Depositories use a variety of markets for liquidity management

Banks turn to several sources to obtain marginal liquidity. The use of each depends on the institution’s requirements and the characteristics unique to the source.

Brokered deposits

The brokered deposit market allows banks, with the permission of their customers, to lend such deposits to other insured depository institutions via third-party brokers. This market is a small subset of the overall deposit liabilities of domestic banks. However, it is of outsized importance for banks’ marginal liquidity needs. Banks of all sizes, especially community banks, rely on brokered deposits for this purpose. While this market is less well-documented than other money markets because it is relatively opaque, the outstanding volumes are typically around $1 trillion (excluding reciprocal deposits), making it one of the largest sources of wholesale funding for domestic banks.

Brokered deposit tenors tend to be longer than overnight for operational simplicity. While public pricing data aren’t available, anecdotally, commercial paper (CP) is considered a reasonable proxy for brokered deposit rates, reflecting links between commercial paper, certificates of deposits (CDs) and brokered CDs.

Commercial paper

CP is one of the oldest money markets and plays an important role financing some large financial institutions, though the market became smaller following the Global Financial Crisis and the ensuing money market fund reforms. Financial institution CP outstanding totals about $670 billion.

The CP market is only a practical source of financing for relatively large issuers, who frequently issue directly to the market. Foreign banks frequently play a large role in issuance due to their dollar funding needs and lack of access to retail deposits. Lenders in this market are often prime money market funds, corporate treasurers and nonbank financial institutions. CP maturities are as short as one day but more frequently are around one month.

Federal Home Loan Bank advances

Like brokered deposits, Federal Home Loan Bank advances are a significant source of marginal liquidity for primarily small institutions, though banks of all sizes use these advances to optimize their liability structures. Advances owed by commercial banks vary significantly over time. They were around $500 billion as of first quarter 2025. While most advances are for a year or less, longer-tenor borrowing is available.

The headline cost of Federal Home Loan Bank borrowing may appear more expensive than other channels for institutions with direct access to instruments such as repo. However, the all-in pricing is lower than the headline rate because Federal Home Loan Bank profits are distributed to members based on advance usage (much like the member dividends paid by recreational equipment cooperative REI). While information on FHLB transactions is somewhat limited, the Federal Reserve Board’s FR 2420 Report of Selected Money Market Rates is expected to begin including advances to and interest-bearing deposits at member banks beginning in 2026.

Federal funds

The federal funds market, often referred to as fed funds, is a primarily overnight market for liquidity between institutions that can hold reserve balances, including banks and government-sponsored enterprises. While it is a historically important money market—it is the market that informs the effective federal funds rate, the Federal Open Markets Committee’s policy target—volumes in this market declined following the Global Financial Crisis. Activity now mostly reflects Federal Home Loan Bank lending to foreign banks. Federal Home Loan Banks need to hold liquidity balances intraday to meet client demand for advances. Thus, they value the early morning return of cash that occurs when lending overnight in fed funds. Because foreign banks are unable to hold retail deposits, this wholesale channel is especially valuable to them as a source of liquidity.

Some domestic banks use fed funds as a marginal source of liquidity, though fewer banks do so than rely on brokered deposits, and the amounts borrowed are much lower. The primarily overnight tenor can be unattractive as a source of liquidity to small institutions that would prefer to avoid the operational burden and risk of rolling their borrowing, and large domestic institutions are more likely to be net lenders. However, many domestic banks, especially certain small ones, lend typically small amounts into fed funds to earn returns on their liquidity holdings.

Given the other lending options available to banks and Federal Home Loan Banks, rates in this market are connected to those in other money markets through arbitrage relationships. However, because of its relatively small size and unusual composition, fed funds activity can be subject to paradoxical effects. Such was the case in March 2023, when bank demand for precautionary liquidity rose, but the fed funds rate remained stable, and volumes dropped.

Eurodollars and selected deposits

Eurodollars refer generally to U.S. dollar deposits held at banks outside the United States. This broader market has played a central role in the history of global finance since World War II. A portion of this market is captured in regulatory reports when banks borrow funds via a non-U.S. branch that are then transferred back onshore within the borrowing institution. “Selected deposits” refer to uncollateralized interest-bearing domestic deposit liabilities with short and fixed terms. These are very similar to Eurodollars but are booked in domestic bank offices. Both Eurodollars and selected deposits are used similarly to fed funds; the main borrowers in these markets are foreign banks. However, unlike fed funds, the primary lenders in these markets are nonbank financial institutions.

Repo

The repo market is the largest market for overnight liquidity. It is a critical source of financing for dealers, hedge funds and other non-depositories. Asset managers (including money market funds) and large depositories do most of the net lending in this market.

Repo transactions take place across multiple segments, typically identified by whether they are centrally cleared and whether they occur on the books of custodial banks. In triparty repo, which occurs on the books of a custodial bank, most of the borrowing activity can be attributed to dealers and foreign banks.

The Fixed Income Clearing Corp. DVP Service is a centrally cleared portion of the market that does not remain on the books of a custodial bank. Transactions in this portion of the market largely occur between dealers, though the composition of this segment has been changing as dealers optimize their portfolios in response to regulation and in anticipation of the adoption of a central clearing mandate for Treasuries.

The repo market famously reacted more strongly than others to the scarcity of reserves that emerged in September 2019. This may seem puzzling, as firms unable to hold reserve balances do much of the lending and borrowing in this market. The outsized repo market reaction is often attributed to the fact that large banks lent less liquidity into this market than usual.

This explanation is true but incomplete for two reasons. First, since delivery-versus-payment repos are settled in reserves, and because repo markets are core to the sourcing of funding for the settlement of Treasury auctions (which also occur in reserves), some repo market transactions generate large flows of reserves. Second, many net borrowers in repo cannot hold reserves themselves, so any reserves shortfall limiting intermediation binds first on them and is reflected in repo market pricing. Recent work has suggested that the supply of money held by non-banks may play an important role in determining what level of reserves is ample.

Though repo is important, like other markets, it reflects idiosyncrasies associated with the purposes for which it is used. For example, it displays monthly seasonality associated with government-sponsored enterprises lending in repo, as their cash holdings increase prior to mortgage-backed securities payment dates. Similarly, around regulatory reporting dates, some banks, especially foreign banks, withdraw from intermediation in repo.

Relationships between money market rates

Individual money markets involve different types of participants, and the borrowing and lending sides in most of these markets tend to involve different types of institutions. Apart from brokered deposits and DVP repo, very little trading of liquidity occurs between financial institutions of the same type.

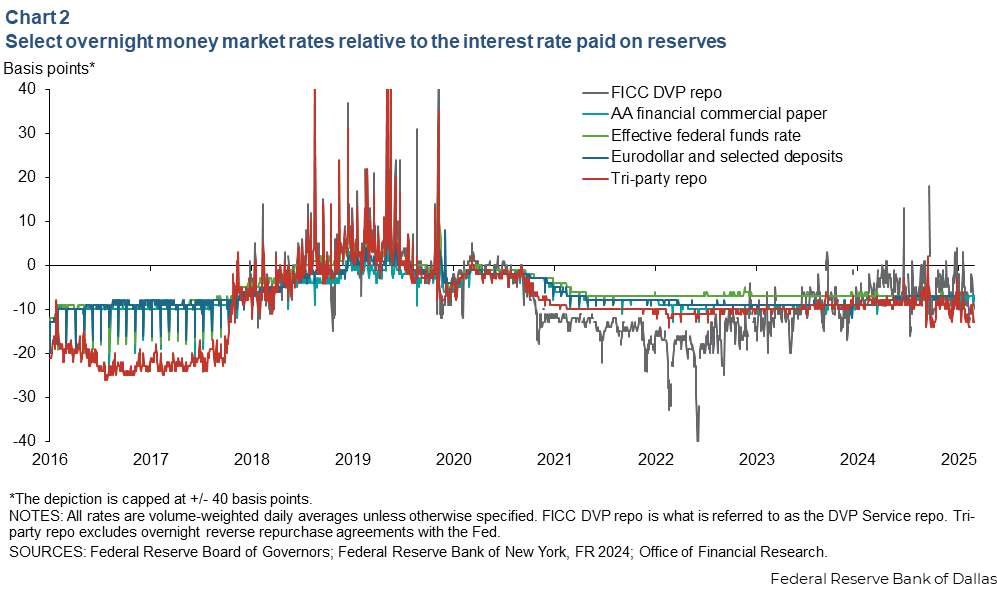

Further, the shortest links between various markets can often run through a single type of entity and at times even a small number of firms. This can at times mean that, due to idiosyncrasies of specific entities and markets, rates in one market may not represent conditions in others (Chart 2).

The effective transmission of policy rates to different corners of money markets is known as pass-through efficiency. Work by Duffie and Krishnamurthy (2016) measured dispersion across money market rates as a primary indicator of pass-through inefficiency, which they showed arises from the various forces that drive the segmentation described here.

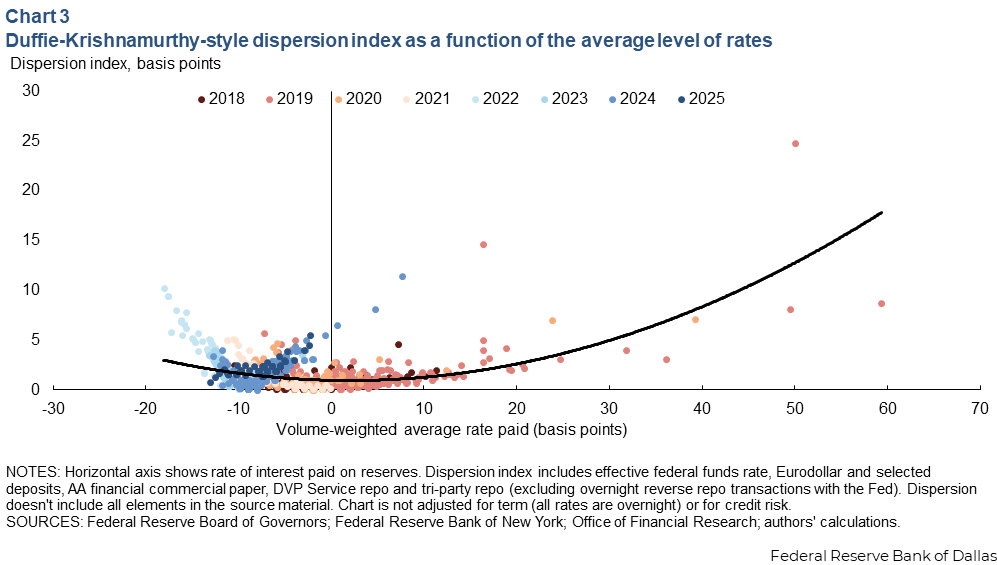

In the vein of this earlier work, we produced a similar index of dispersion using publicly available data for the markets described here. Unlike the earlier authors, we do not apply a credit adjustment, as we find unsecured rates are less responsive than secured rates to market liquidity shocks due to the idiosyncrasies in unsecured interbank markets. Additionally, we do not adjust for term, as only overnight rates are used.

Pass-through efficiency is highest when money market rates broadly remain near the rate of interest on reserves, which appears broadly consistent with how the outside option provided by policy rates functions in the model in the original paper.

Dispersion tends to be lowest when the level of reserves is consistent with the average level of money market rates being close to the rate of interest the Fed pays on reserves (Chart 3).

The basic intuition about this result is straightforward and arises from two basic facts. First, when rates in money markets fall below the interest rate on reserves (IOR), banks have an incentive to borrow in those markets and earn the spread; similarly, when rates in money markets rise above IOR, banks have an incentive to economize on their reserve holdings and lend into those markets. Second, banks have regulatory and other limitations on the degree to which this intermediation activity is economical for them. It follows that intermediation capacity is less binding when money market rates are closer to IOR, maximizing the pass-through of policy rates and, thus, minimizing dispersion.

Network structure affects policy rate pass-through

The structure of the network of entities and markets varies over time and is a critical determinant of rates across markets. Some of the markets bank treasurers typically rely on to manage liquidity also generate significant client flows that impact bank reserves. The pass-through efficiency of policy rates as measured by dispersion is highest when reserves are at a level consistent with money market rates typically remaining close to IOR. This arises from both bank incentives and limits on intermediation capacity.

One example of the impact of intermediation capacity on rate dispersion follows from the effects of foreign banks withdrawing from repo intermediation around quarter-ends. It can dramatically affect pricing, as intermediation demands on domestic banks increase in response to the temporary shift in the network structure away from its natural optimum.

The intuition that arises from understanding the relationship between the network structure of money markets, intermediation capacity and rate dispersion has useful applications when monitoring reserve scarcity and understanding how it evolves in response to changes in regulation, market structure and other factors.

About the authors