Monetary policy in time of pandemic

What role, if any, is there for monetary policy in addressing the coronavirus (COVID-19) threat? The monetary policy discussion is narrower than a discussion of the role of the Federal Reserve during pandemics because the Fed has important responsibilities besides monetary policy.

Notably, the Fed is charged with promoting the safety, soundness and smooth functioning of the nation’s financial system. In current circumstances, however, the Fed’s monetary policy and financial stability roles overlap. Some monetary policy strategies have greater potential than others to mitigate pandemic-related financial strains.

COVID-19 threat

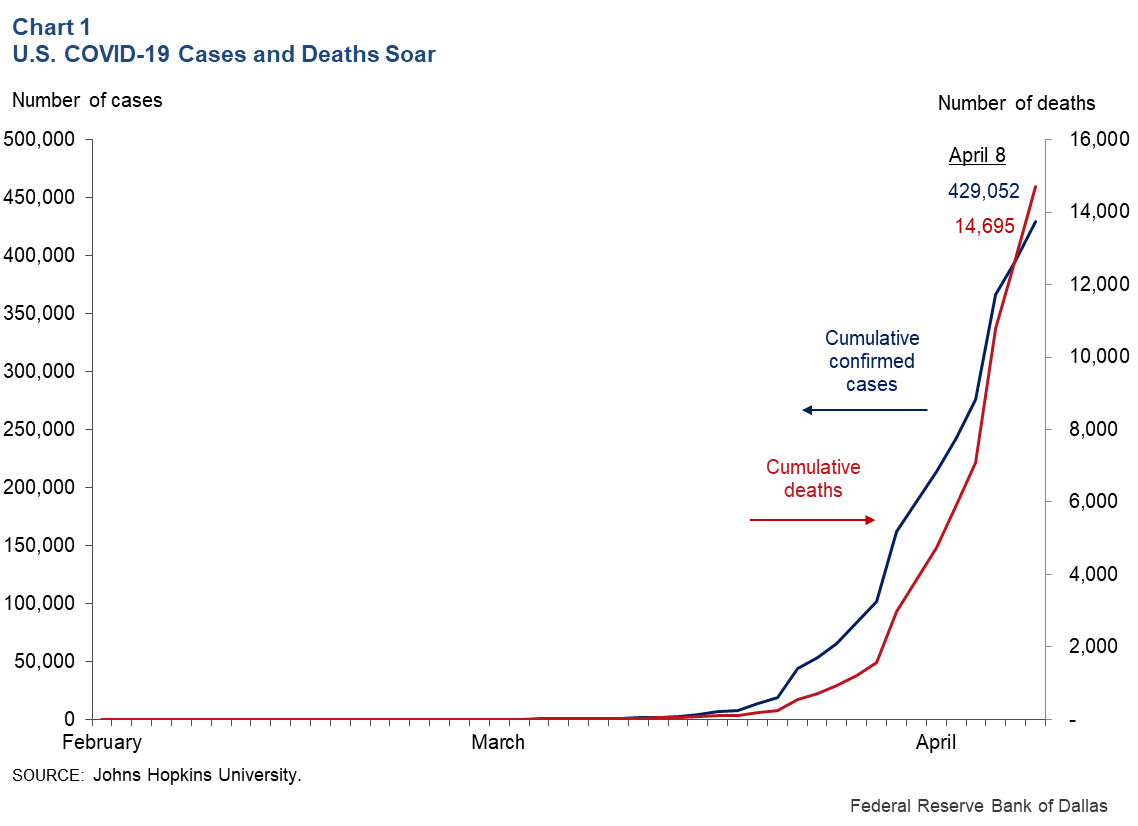

As of April 8, there were more than 429,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the United States and nearly 14,700 deaths (Chart 1). The threat is enormous and frightening. COVID-19 is reported to be more infectious than the common flu, and an order of magnitude more deadly.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that the flu infected 35.5 million U.S. residents in the 2018 season, accounting for 34,200 deaths. Those figures suggest that without strong action, COVID-19 cases might easily have risen into the tens of millions, with deaths exceeding the number of U.S. soldiers killed in action during World War II (292,131).

COVID-19 and restrictions designed to limit its spread have effects on the economy similar to those of a severe winter snowstorm. Workers can’t get to their jobs and consumers can’t get to stores, restaurants and other retail outlets, but there is little or no damage to equipment and facilities. Both supply and demand are adversely affected.

Differences in scale and in kind

Most weather-related disruptions, though, are localized and transitory, and the resultant hardships are relatively easily addressed using targeted, temporary aid programs. The finances of some businesses and households take a hit, but there is no threat to the financial system as a whole.

Moreover, weather-related disruptions are largely outside of anyone’s control. In contrast, a significant fraction of the economic damage associated with COVID-19 is the result of government restrictions designed to limit the disease’s spread. Government action is essential to offset our tendency as individuals not to fully take into account the risks that our behaviors pose to others.

Consciously or not, political leaders weigh the costs of disease against the costs of disease prevention. A monetary policy strategy that mitigates the economic damage caused by preventive measures might tilt this balance toward saving lives.

Pandemic-related financial strains

COVID-19 incapacitates a portion of the potential labor force and reduces the productivity of those who continue to work. If retailers are in the business of making goods and services conveniently and safely available to the public, then communicable diseases such as COVID-19 amount to an unmeasured deterioration in the quality of retail services—an adverse supply shock.

In an office or factory setting, the possibility that co-workers are infected discourages face-to-face collaboration. Government-mandated event cancellations, business closures and shelter-in-place orders further reduce real economic activity. Absent any increase in wages and prices, therefore, the dollar values of workers’ incomes, business revenues and government tax receipts all sharply decline.

The threat to the financial system comes from the fact that nearly every household, business and government has obligations that are fixed in nominal terms: home and car payments, office and equipment leases and pension obligations, for example.

With less money coming in, households, businesses and governments quickly find it difficult—and in some cases impossible—to meet their obligations. This cash-flow squeeze can potentially lead to a wave of loan defaults, business failures and personal bankruptcies. Those events, in turn, can have profound, persistently negative implications for the economy.

How can monetary policy help?

An article I published in the International Journal of Central Banking in 2013 looks at optimal monetary policy strategy in an economy where people have fixed nominal debt obligations amid fluctuations in real activity. The article points out that absent an increase in the price level, the entire burden of declines in real output falls on those with fixed nominal debt obligations. Creditors are completely protected (unless debtors default).

In contrast, a monetary policy that allows the price level to increase in response to unexpected declines in output so that nominal gross domestic product (GDP) holds steady achieves exactly the same risk-sharing outcome as an economy with a complete insurance market. Specifically, the increase in the price level reduces the real (inflation-adjusted) value of debt-service payments by just enough that the real incomes of debtors and creditors fall by equal percentages.

The key takeaway is that an economy in which people have fixed dollar obligations functions best when aggregate dollar income follows a predictable path. To the extent that monetary policy can provide that predictability, it spreads recession risk, reducing financial-system stress. In the present context, the Fed’s monetary policy goal should be to limit the fall in nominal GDP due to COVID-19 and COVID-19 control efforts.

Monetary policy’s limitations

Monetary policy is far from being a panacea. It certainly cannot eliminate the disruptions to production and employment caused by COVID-19 and efforts to limit its spread. Its control of nominal GDP is also imperfect.

Moreover, monetary policy is a blunt instrument. It is incapable of targeting assistance to especially hard-hit sectors of the economy or specific geographic regions. For that purpose, fiscal policy, or fiscal policy coordinated with Federal Reserve intervention in credit markets, may be the better option. As observed by former Fed Governor Jeremy Stein, though, there is considerable value to a tool like monetary policy that “gets in all of the cracks.”

Currently, maintaining nominal GDP growth is especially difficult because, with interest rates across the maturity spectrum already at very low levels, central bank purchases of Treasuries (pure monetary policy) are, by themselves, unlikely to provide much stimulus to spending. What the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) still can do is commit to offsetting near-term spending shortfalls so that when averaged over several years, nominal GDP growth does not disappoint.

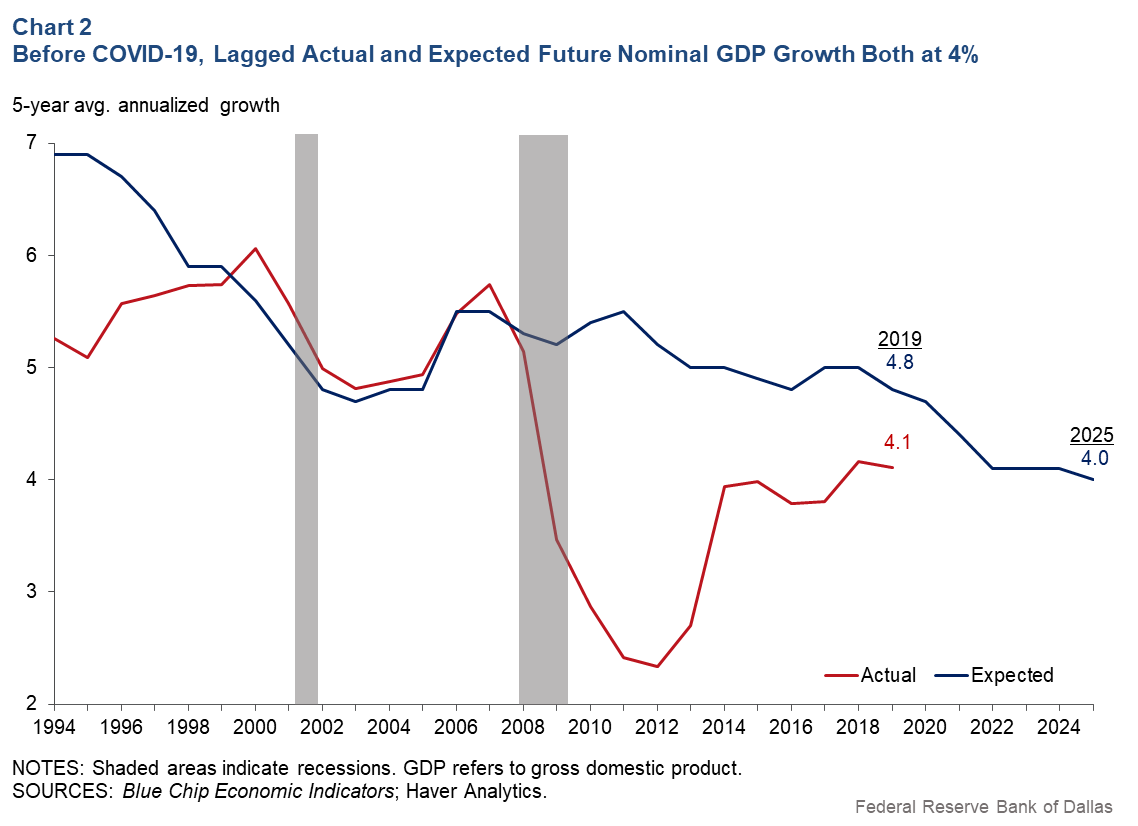

A recent survey of forecasters suggests that the FOMC should shoot for 4 percent nominal growth, on average, over the next five years—roughly matching actual growth over the past five years (Chart 2). Nominal GDP growth of 4 percent is fully consistent with the FOMC’s 2 percent longer-run inflation objective, provided that five-year average real growth matches the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of the U.S. economy’s growth potential (2 percent).

If households and businesses are confident that near-term shortfalls in income and revenue growth will be made up, they (and their creditors) will be reassured that today’s cash-flow problems are temporary. That reassurance—coupled with unemployment insurance, emergency bridge loans and targeted fiscal assistance—will go a long way toward keeping the financial sector in good health, setting the stage for a rapid economic recovery once COVID-19 has been brought under control.

A supporting role

The Fed’s monetary policy actions did not cause this recession, and they aren’t likely to be the main driver of the expansion that follows. But monetary policy can play a role in limiting the economic and financial damage caused by efforts to contain COVID-19 and, in that way, can help support the strict public-health measures that are needed to save lives and set the stage for economic recovery.

A supportive monetary policy is one that is oriented toward maintaining growth in nominal GDP, with a commitment to make up for any near-term nominal-growth shortfalls.

About the Author

Evan F. Koenig

Koenig is a senior vice president in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.