U.S. likely didn’t slip into recession in early 2022 despite negative GDP growth

Has the U.S. economy entered a recession?

Recession is often defined as two consecutive quarters of economic contraction—declining real GDP. The nation’s GDP fell 1.6 percent on an annualized basis in first quarter 2022 and was followed by a 0.9 percent drop in the second quarter.

However, we find that most indicators—particularly those measuring labor markets—provide strong evidence that the U.S. economy did not fall into a recession in the first quarter.

The two quarters of declining GDP definition is a rule of thumb that does not officially define a recession. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Business-Cycle Dating Committee, which certifies and dates U.S. business cycles, defines a recession as “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months.” A range of monthly indicators has been used by the committee to determine the peaks and subsequent troughs in economic activity. The period between the peak and the bottom of a subsequent downturn is called a recession.

There is no fixed rule for weighting these indicators, and it often takes the committee several months or years to determine a business-cycle peak or trough. To answer whether the U.S. economy fell into recession, our analysis compares the movements of the indicators cited by the NBER committee in 2022 with those in previous recessions.

Inspecting individual recession indicators

The NBER committee’s indicators used to date business cycles include real (inflation-adjusted) personal income minus transfers, nonfarm payroll employment, employment as measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics household survey, real personal consumption expenditures, wholesale-retail sales adjusted for price changes and industrial production.

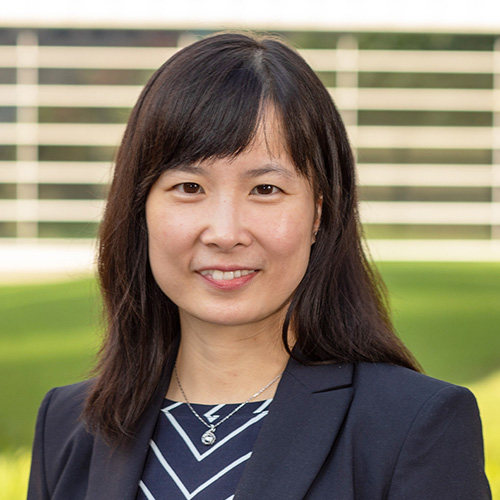

The gray lines in Chart 1 show the movements of nonfarm payrolls and industrial production in each previous business cycle relative to the peak of that cycle (month 0 = 100); the average across all previous cycles is the black line. The 2020 COVID-19-induced recession is excluded because its cause, scale and timing were extremely atypical. The red line is the indicator’s movement between June 2021 and June 2022 relative to the level in December 2021.

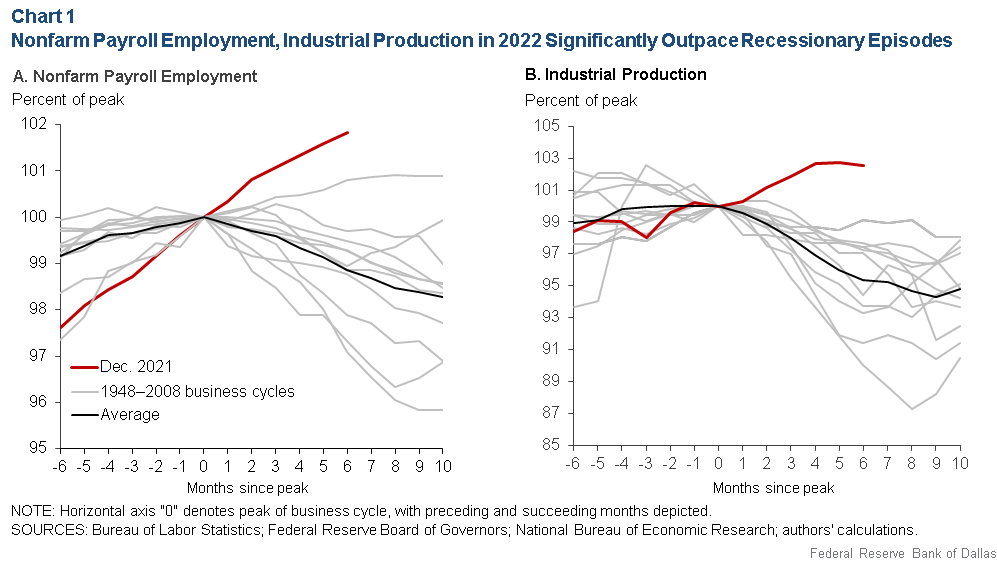

The data show that employment in the overall economy and output of the industrial sector in 2022 have significantly outperformed what occurred during every previous recession at a similar point. Chart 2 repeats this exercise for an alternate source of employment (surveying households rather than businesses) and for manufacturing and trade sales.

While these indicators in 2022 (red line) are not as starkly above the gray recession lines as the indicators in Chart 1, their paths remained at the higher end of the distribution and were notably higher than the corresponding average recession paths. These indicators are also more volatile than their counterparts in Chart 1, with a wider range of recessionary outcomes.

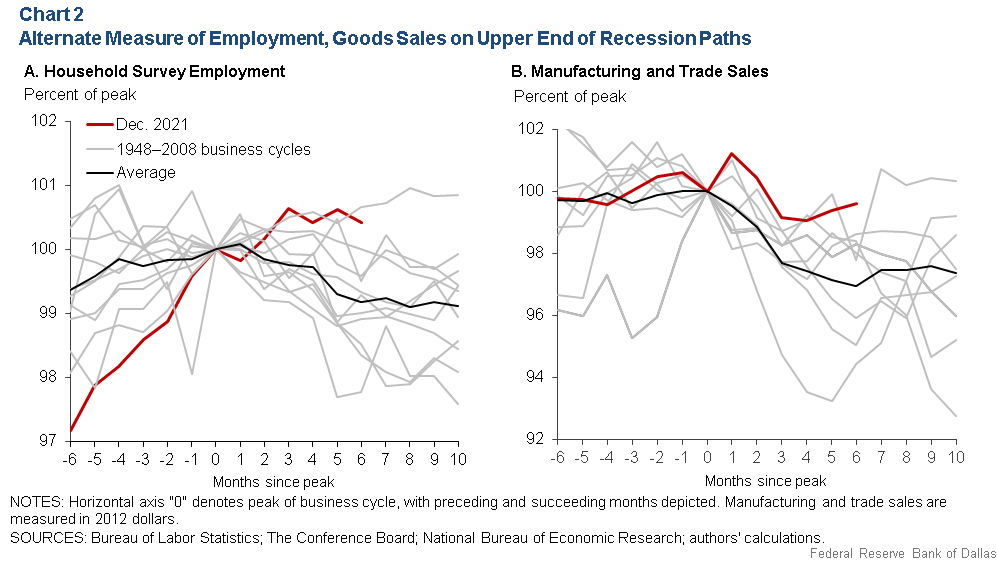

Finally, Chart 3 shows a similar pattern as Chart 2 for real consumption and real personal income excluding transfers.

A composite index of recession indicators

To visually summarize the indicators considered by the NBER committee, we construct a composite index of recession indicators. We use a similar methodology to the Conference Board’s composite index of coincidence indicators but add household survey employment and real consumption to the four included in the Conference Board index.

The growth rate of our index is the weighted average of the six indicators, with weights inversely proportional to the standard deviation of the monthly growth rate of a given indicator. This emphasizes the more stable indicators, such as employment and income, and underweights volatile components such as manufacturing and wholesale-retail sales.

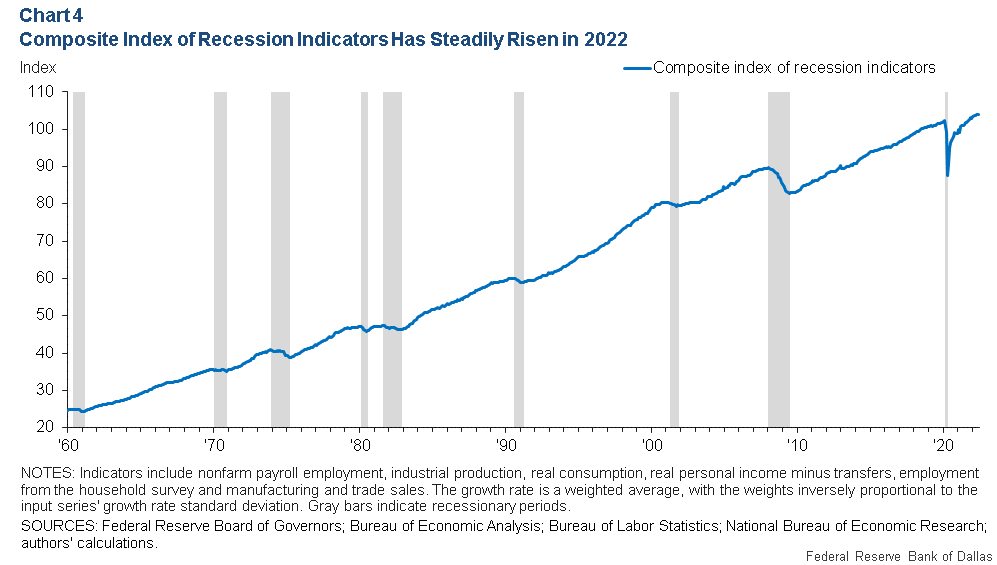

Our index, which begins in 1959, declined from the peak point in every previous recession; by comparison, the index steadily rose from December 2021 to May 2022 and was unchanged from May to June (Chart 4).

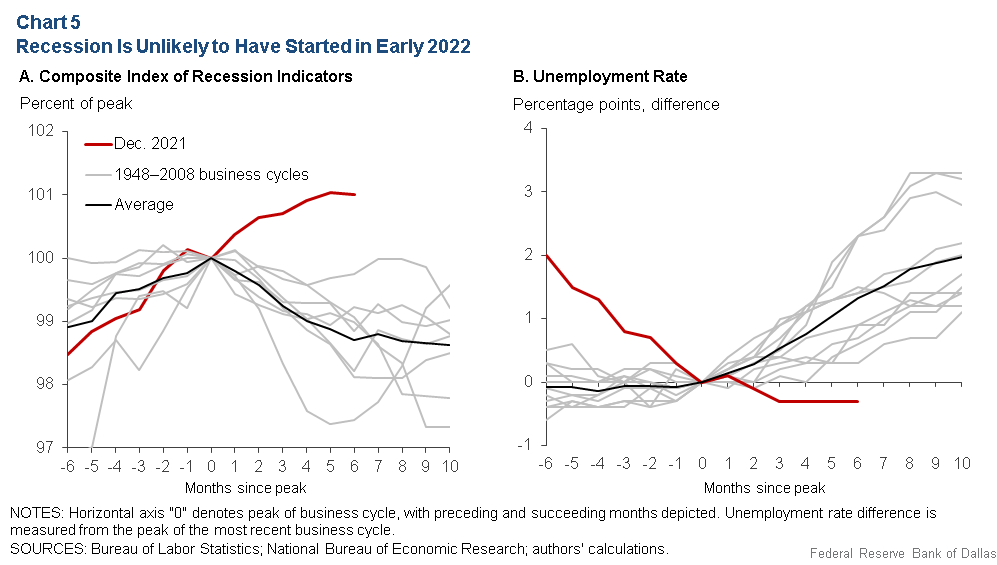

Chart 5, Panel A shows the paths of our index in previous recessions and in 2022. It dipped below 100 within two months of the peak in every previous recession. By the sixth month, the average recession had a value of 98.7. By comparison, six months into 2022, the June index was 101.0, significantly above the path of a typical recessionary period.

The sharp contrast between the index’s average recession path and the six-month path in 2022 suggests that a recession is unlikely to have started in first quarter 2022, despite two consecutive quarters of declining GDP in the first half of 2022. If we were to assign a higher weight to labor market indicators, this contrast would be even more stark.

The U.S. labor market as measured by the employment count has held up especially strongly in 2022 relative to past recessions, and a broad set of indicators suggests continued labor market tightness through the first half of the year.

Low unemployment rate is also argument against recession

While not listed among the indicators considered by the NBER committee, the unemployment rate is also among the indicators pointing to labor market strength through the first half of 2022 (Chart 5, Panel B). It has declined from 3.9 percent in December 2021 to 3.6 percent in March 2022, where it has held steady through June. By month six, every other recession incurred an unemployment rate increase of at least 0.3 percentage points.

Increases in unemployment may also better match conceptually what is generally understood to mean a recession—an increase in slack or underutilization of resources rather than a decline in economic activity. As trend GDP growth slows due to aging demographics and slower productivity gains, there may be more frequent periods of negative GDP growth without an increase in unemployment, making the distinction between increasing slack and declining activity more relevant than in the past.About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.