Individuals, married couples respond differently to U.S. income tax changes

While income taxes have been around for a long time—the federal income tax since 1913—their structure has frequently changed. Tax law changes can significantly affect labor supply, income and savings, we show in our recent paper. The paper evaluates how federal effective income taxes—taxes that people actually paid—have evolved for American couples and singles.

We also provide an overview of income tax law reform from the 1960s to better understand the rationale for the changes, the economic environment in which they took place and how they translate into effective taxation. We found that changes in effective income taxes can impact labor supply with different outcomes for married couples and singles, and changes can have a particularly notable impact on married women.

Effective taxation varies with household type

Differential taxation by marital status became a feature of the federal income tax system after the Tax Reform Act of 1969. It established that beginning in 1971, unmarried individuals would be taxed under a different tax schedule than married people.

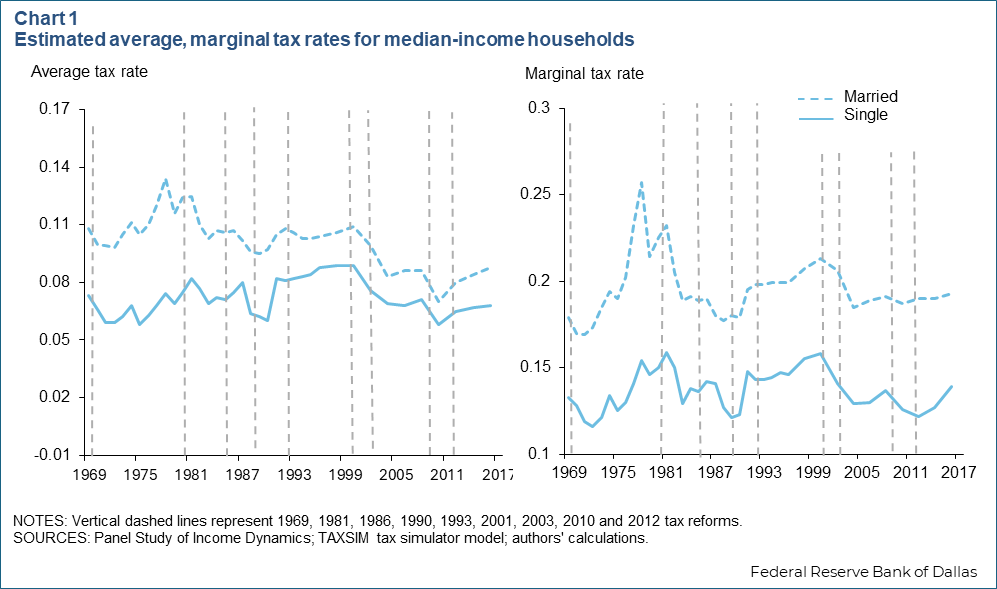

The average tax rate is always higher for a median-income married couple than for a median-income single (Chart 1). Over the period we consider, the average tax rates for each were at their lows in 2010, at 5.8 percent for singles and 7.0 percent for married couples. Their maximum values were 8.9 percent in 1998 for singles and 13.4 percent in 1978 for married couples.

The U.S. income tax is progressive. Thus, the marginal tax rate, the tax rate paid on the last dollar earned, is larger than the average tax rate. The marginal tax rate for median-income singles varied between a low of 11.6 percent in 1972 and a high of 15.9 percent in 1981. The marginal tax rate has been substantially greater for median-income married couples, from a low of 16.9 percent in 1971 to a high of 25.7 percent in 1978.

Reforms have been frequent

The average tax rate for married and single households trended higher in the 1970s. The Tax Reform Act of 1969, under President Richard Nixon, temporarily reduced taxes, though effective taxes rose throughout the decade.

For example, the average tax rate for median-income singles rose from 6.6 percent under Nixon in 1970 to 6.9 percent under President Jimmy Carter in 1979. For married couples during the period, the average rate rose from 10 percent to 11.6 percent.

Meanwhile, the marginal tax rate increased substantially from 1972 through 1978, by 8 percentage points for married couples and by 4 percentage points for median-income singles.

The eight-year Ronald Reagan presidency and the start of the George H.W. Bush administration spanned the 1980s. The average tax rates for median-income couples and singles decreased by at least 3 percentage points following the Reagan administration’s Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 and the Tax Reform Act of 1986.

However, in the 1990s under President Bush, taxes rose. In a bid to reduce the federal budget deficit, effective taxes increased under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990. President Bill Clinton attempted to further boost taxes under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993. However, effective taxes changed little between 1992 and 1993.

Income tax rates decreased in the first decade of the 21st century during the George W. Bush administration. After 2001 and 2003 reforms, the average tax rate for the median-income married couple decreased from 10.9 percent in 2000 to 8.6 percent in 2008, and for singles from 8.9 percent to 7.1 percent.

Between 2010 and 2016, because rising incomes following the Great Recession pushed people into higher tax backets, average effective tax rates increased despite reforms under President Barack Obama in 2010 and 2012. The average tax rate for median-income couples grew 1.8 percentage points from 2010 to 2016 and rose for median-income singles 1 percentage point.

Changing tax regimes affect behaviors

We use an estimated dynamic quantitative model of the labor supply, consumption and savings decisions of couples and singles over their life cycles, from youth to elder years, to evaluate the extent these tax regimes affected key economic behaviors. Our focus was on individual and household outcomes; we take no stand on the effects of tax reforms on government tax revenue or deficits.

Our results show that changes in effective income taxes can spur or depress labor supply (and consequently income and savings), with especially large effects on the outcomes for married women.

Our results for the major tax reforms since the 1970s illustrate these effects.

The increase in effective taxation during the 1973–78 high-inflation tax period significantly and negatively affected the labor supply of couples and singles. Under the 1978 tax regime, the labor force participation rate for young married women was 9.4 percentage points lower than under the 1973 regime. Hours worked were 5.1 percent lower for married women, 2.4 percent lower for married men, 4.5 percent lower for single women and 1.7 percent lower for single men over the first 10 years members of each group worked.

Meanwhile, labor income declined 20.2 percent for young married women, 3.1 percent for married men, 6.2 percent for single women and 2.1 percent for men. Savings dipped 6.3 percent for couples, 4.5 percent for single women and 6.0 percent for single men.

The 1981 Reagan tax cut also affected behaviors, although in an opposite direction and to a slightly smaller extent. Notable also are the 1986 Reagan tax cut, the 1990 Bush tax increase, and the 2001 and 2003 George W. Bush tax cuts, which especially affected the participation of married women, who typically were more responsive to the changes than their spouses. The 2010 Obama tax cut extensions increased hours worked over the first 10 years of work 1.4 percent for single women and 0.7 percent for single men.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, the Federal Reserve System or National Economic Research Associates Inc.