How sensitive is the Treasury cash-futures basis trade to funding condition shifts?

Asset managers’ widespread use of Treasury futures to gain synthetic duration exposure is a well-known feature of the U.S. fixed income market. This structural long positioning requires an offset, typically found in leveraged funds that take the short side of the trade.

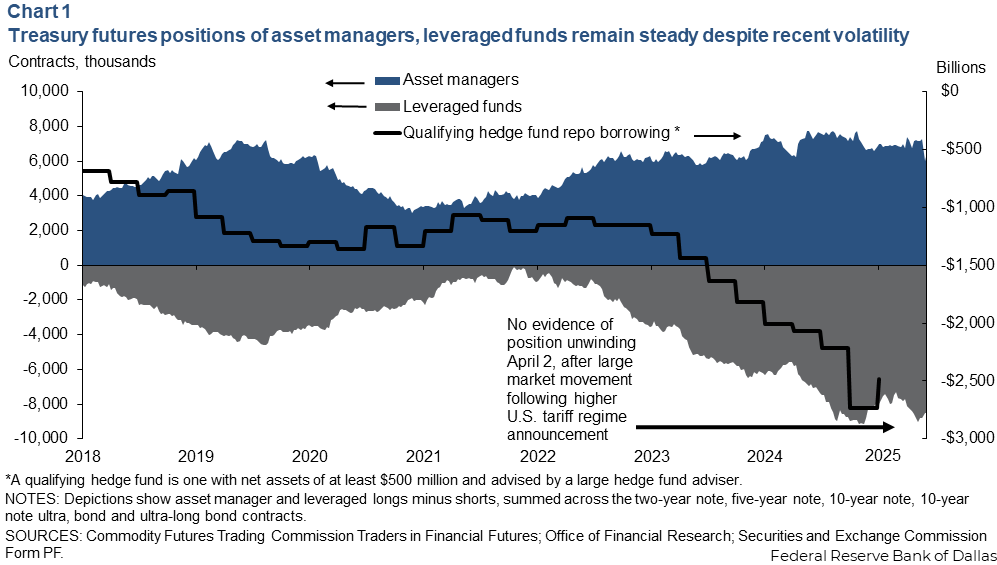

Importantly, the growth in net short futures positions among leveraged funds has accompanied a notable increase in hedge funds’ Treasury repurchase (repo) market borrowing, pointing to the prevalence of Treasury cash-futures basis trades (Chart 1).

A Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee presentation in January 2024 documented the incentives behind asset managers’ preference for Treasury futures. But regardless of the underlying drivers, this trend has raised financial stability concerns among policymakers about potential vulnerabilities in the Treasury market. These concerns are not merely theoretical: The rapid unwinding of basis positions amplified Treasury market stress as the pandemic took hold in March 2020.

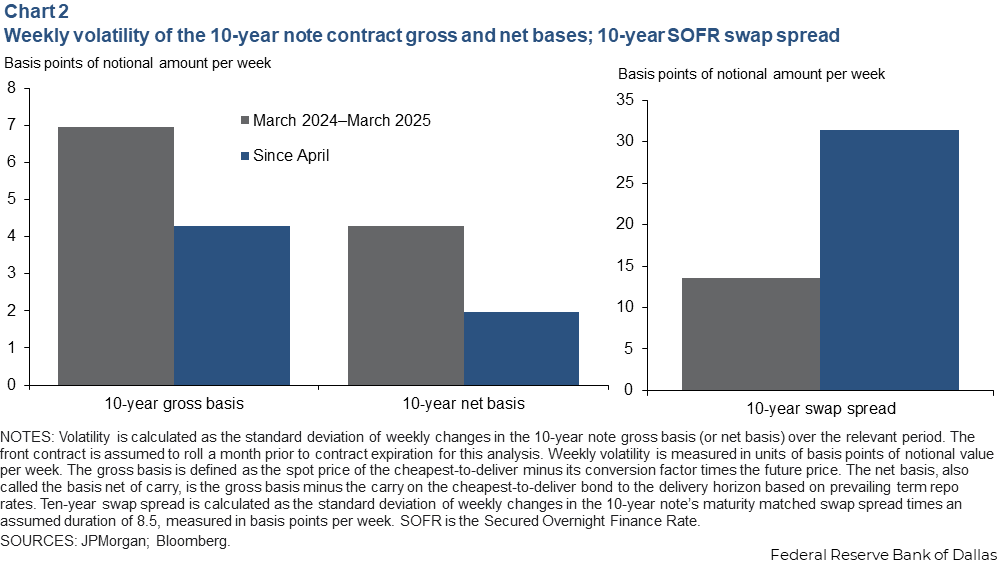

In contrast, basis positions were notably stable during the market turbulence in April 2025 following the announcement of higher U.S. tariffs. Despite a sharp rise in Treasury market volatility, Treasury futures positioning was little changed, and cash-futures bases were largely unaffected. This compared with other Treasury market differentials such as swap spreads, where volatility surged (Chart 2).

We examine some key risk exposures embedded in the basis trade (excluding margin-related risks), especially the sensitivity to funding conditions. We conclude by exploring other risk factors that may help explain the resilience of basis positions given recent market volatility.

Risk factors in a Treasury cash-futures basis trade

Treasury futures are physically settled, meaning the short is obligated to make delivery of one of a predetermined set of eligible bonds (the basket) within a specified delivery window. As a result, Treasury futures can be thought of as essentially forward purchase contracts on the current cheapest-to-deliver (CTD) bond, with an additional adjustment for embedded optionality (since the short has the right to switch either the bond to be delivered or the timing of delivery or both, should that become advantageous).

The optimal bond to deliver and the optimal delivery time within the window are determined by market factors such as yield levels, slope of the yield curve and volatility, as well as financing rates. As such, the short also possesses an option on yield levels and the yield curve, whose economics are reflected in a downward adjustment to the futures price. In essence, the short gains flexibility and pays for it in the form of selling futures at a discount. The valuation of this option is beyond the scope of this discussion but is discussed elsewhere (see G. Burghardt & T. Belton, 2005).

A conversion factor is also involved. It is a mechanism designed to normalize the pricing of bonds in a basket with various coupons and durations by assigning scale factors to each bond (see CME methodology on conversion factors). While conversion factors affect basis trade hedge ratios and introduce algebraic complexity in basis calculations, they are not central to our discussion. For the purposes of our discussion here, readers unfamiliar with Treasury futures will likely benefit from assigning all conversion factors a value of one.

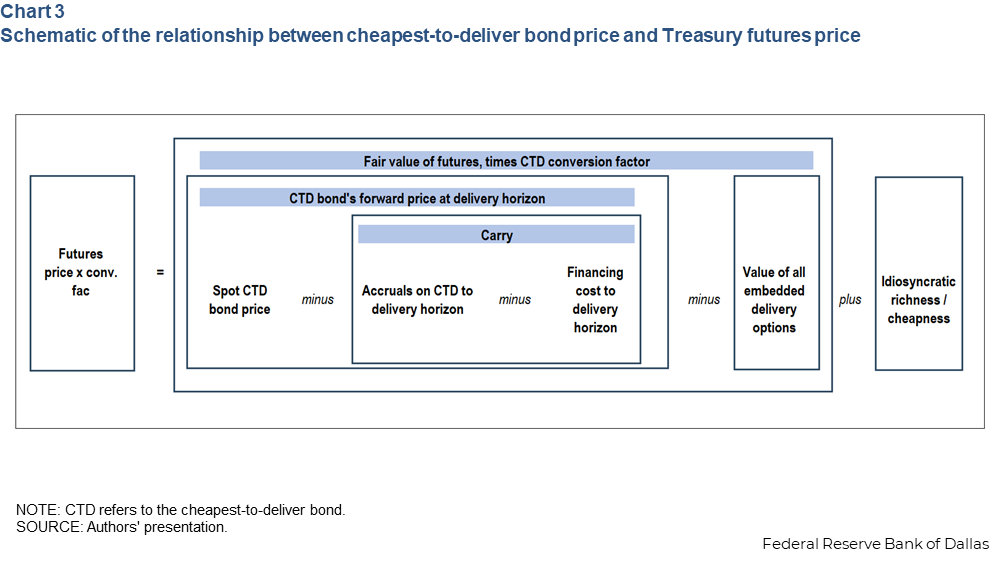

The relationship between the cheapest-to-deliver bond price and the futures price provides a useful lens to understand the terminology, mechanics and motivations behind basis trades.

First, there is the gross basis, defined as the cheapest-to-deliver bond’s spot clean price, minus the conversion factor times the futures price. (The clean price excludes accrued interest.) The gross basis is merely the sum of carry, delivery option value and any idiosyncratic mispricing in futures relative to fair value.

It is important to note that carry does not contribute to returns in a basis trade (although changes in carry can). This is because the pricing relationship illustrated in Chart 3 holds at all times before delivery. Thus, over time, positive carry earned on the bond leg of the trade decreases the remaining carry, producing a corresponding increase in the futures price, leaving net returns from carry effectively neutral. When carry on the cheapest-to-deliver bond is negative, the carry cost incurred on the bond leg is offset by a downward drift in the futures price, again resulting in zero net impact on profitability.

Given this, an investor’s motivation for entering a long basis trade—for example, buying the cheapest-to-deliver bond and selling the futures—must fall into one of three categories.

- Relative value: The futures contract is idiosyncratically rich relative to the cheapest-to-deliver bond, implying the basis is too narrow, and the delivery options are underpriced.

- Option value: The delivery options embedded in the contract are undervalued or there is a desire to own the embedded delivery option. For example, this could reflect anticipation that yield levels will rise, with larger increases in longer maturities that would likely produce increases in delivery option value in some contracts under current market conditions.

- Financing rates: Financing rates will not remain constant. For example, a decline in financing rates to delivery would increase carry, cheapen futures and widen the basis.

Notably, although holding a view on changes in financing rates is a plausible reason to enter a long-basis trade, it is unlikely in practice. Acting on anticipated short-term rates is simpler and more efficiently done through fed funds or Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) futures, which offer off-balance-sheet exposure without the operational complexity of a basis trade.

Thus, it is reasonable to assume that most long-basis positions held by sophisticated investors are likely hedged against moves in short-term rates and are, instead, motivated by relative value considerations or desire to own delivery optionality. For such investors, financing rate moves are not a risk factor in their basis trades.

But even for investors holding basis positions unhedged for financing rate risk, moves in financing rates are not especially likely to trigger large-scale deleveraging. This is because the remaining time to delivery is never more than three months, limiting the carry consequences of any moves.

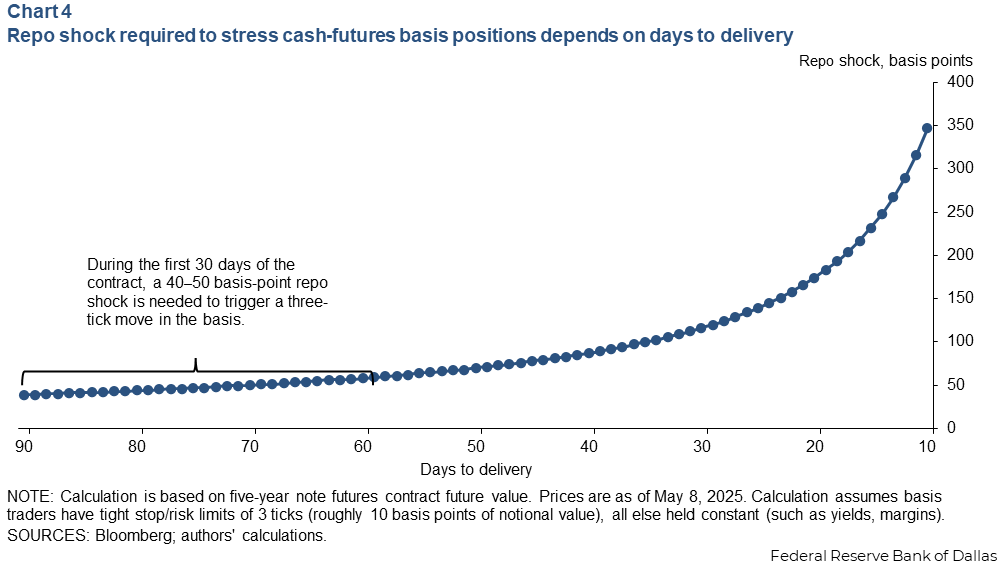

There is an inverse relationship between the size of a funding rate shock and the basis response (Chart 4). Even with a full three-month horizon, it would take a 40- to 50-basis-point increase in repo rates to induce a roughly 3-tick move in the basis (futures market convention is to measure price changes in ticks or 1/32nds of a point, making 3 ticks the equivalent of approximately 10 basis points of the notional amount).

This is significant because a 3-tick move is likely at the lower end of the range of moves that could trigger some de-risking of basis positions by participants unhedged against financing risk. Across the six major Treasury futures contracts, the monthly volatility of the net basis (calculated as the standard deviation of daily changes in the net basis over five years, scaled up to a one-month horizon) has been about 3 ticks.

Thus, an investor holding a long basis position for a month should expect an adverse move of this size (or greater) about one-third of the time. Since the natural holding period for basis trades tends to be a month or longer, it is unlikely that moves smaller than 3 ticks would lead to much deleveraging.

Intermediation capacity matters more than financing rates

The discussion thus far suggests that unexpected shocks to financing rates are an unlikely major threat to basis positions. This is partly because large basis investors typically hedge against such risk and partly because the magnitude of rate moves required to prompt de-risking among unhedged investors is relatively high. However, the availability of adequate intermediation capacity among both hedge funds and dealers is critical for basis positions.

Dealer intermediation capacity affects the basis trade directly. Dealers’ inability to absorb additional sales of cash Treasuries cheapens them relative to futures when dealers are the marginal buyers. Dealer intermediation capacity also affects the basis trade indirectly through a contraction in the supply of repo funding to hedge funds, reducing the hedge funds’ balance-sheet capacity. Because of this reliance on dealer-intermediated repo, basis trades remain vulnerable to forced unwinds in the event of sudden reduction in the ability or willingness of dealers to intermediate Treasury repo funding.

One likely manifestation of such constraints on balance-sheet capacity would be a large divergence between implied and actual term repo rates. The implied repo rate represents the rate at which the following arbitrage relationship holds:

Futures Price x Conv. Fac. = Spot CTD Price – (Accruals – Financing Cost using Imp. Repo)

Thus, the implied repo rate effectively represents a breakeven financing cost of holding the basis trade, incorporating not just expected funding rates but also the value of embedded delivery options and any idiosyncratic mispricing between the futures and the underlying bond. As such, comparing implied repo rates to actual cheapest-to-deliver (CTD) bond financing rates provides a useful way to detect mispricings, especially in sectors with minimal delivery optionality.

As might be expected, such mispricings can become more pronounced during episodes when dealer intermediation capacity becomes scarce relative to the supply of Treasuries, causing implied repo rates to diverge significantly from actual repo rates.

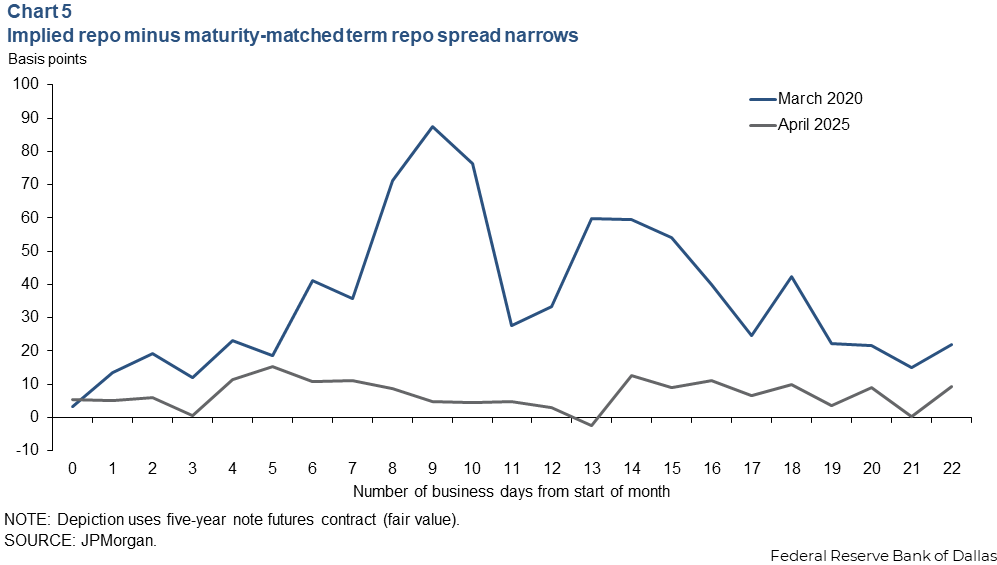

For example, a sharp unwinding of long basis positions would typically lead to a cheapening of the basis and, consequently, an increase in implied repo rates relative to term repo rates. This dynamic was observed in March 2020, when the spread between implied and actual term repo for the June five-year note contract widened by 50 basis points before policy intervention helped restore market functioning (Chart 5).

In contrast, despite significant volatility across markets, no such rise in implied repo rates was observed in April 2025. This suggests that even as shifting macroeconomic expectations sparked volatility in asset prices, availability of repo funding and intermediation capacity more broadly remained stable, likely explaining the resilience of basis positions in recent months.

Right-way versus wrong-way risk

The stability of basis positions in April may also have been supported by right-way exposure to recent developments on three fronts. First, long basis positions gain from higher volatility (which increases delivery option value) if the rise in volatility stops before triggering higher margin requirements. Second, these positions benefit from rising expectations of policy easing (which decrease financing rates and help long basis positions unhedged against short-term rate moves). Third, the recent trend of higher yield levels (with longer maturity yields rising more than shorter maturities) also likely favored long basis positions.

In recent quarters, cheapest-to-deliver bonds have tended to be near the short-duration end of the deliverable basket. From that starting point, a rise in long-end yields or a steepening of the yield curve cheapen the longer-duration bonds relative to shorter ones, increasing the likelihood of a cheapest-to-deliver switch and widening the current basis.

Long basis positions have recently benefited from a confluence of favorable conditions: sustained availability of dealer intermediation capacity, higher volatility, rising yields, curve steepening and, in some cases, falling short-term rates. All were notable following the announcement of plans for sharply higher U.S. tariffs on April 2, 2025.

However, this alignment of risks may not always be favorable. In a future episode, economic or policy developments could shift these dynamics and prompt sudden de-risking, even in the absence of direct funding stress.

About the authors