I. A unique balance of college autonomy and statewide coordination

Oversight of higher education varies from state to state, and the Texas community college system is unique. The state’s two-year institutions are at once highly decentralized and coordinated by a central authority, an unusual federalist balance that has consequences for funding, quality control and how colleges engage with business and industry to shape workforce education.

This distinctive mix of local autonomy and statewide coordination has roots in the diversity of the state economy. Texas community colleges are funded largely by local property taxes and have wide discretion to chart their own course, offering programs and building local relationships to meet the needs of their communities (See map ). But the statewide higher education agency also wields considerable influence, providing support and making recommendations to the Legislature, including about funding.

Like all federalist power sharing, this balance comes with challenges and opportunities for leadership seeking to encourage colleges to rethink priorities.

What makes each college different starts, but does not end, with size. A tiny school with 1,400 students is not just a smaller version of a vast, multicampus college serving nearly 100,000 learners. It is a different type of institution, with different ambitions and needs.

Adding to this diversity is the huge variation in the taxing districts that support Texas community colleges. The economy is expanding much faster in some parts of the state than in others. The population is growing rapidly in some places and shrinking in others. Even as the state population skyrocketed between 2010 and 2020, more than half of Texas counties lost people.[16]

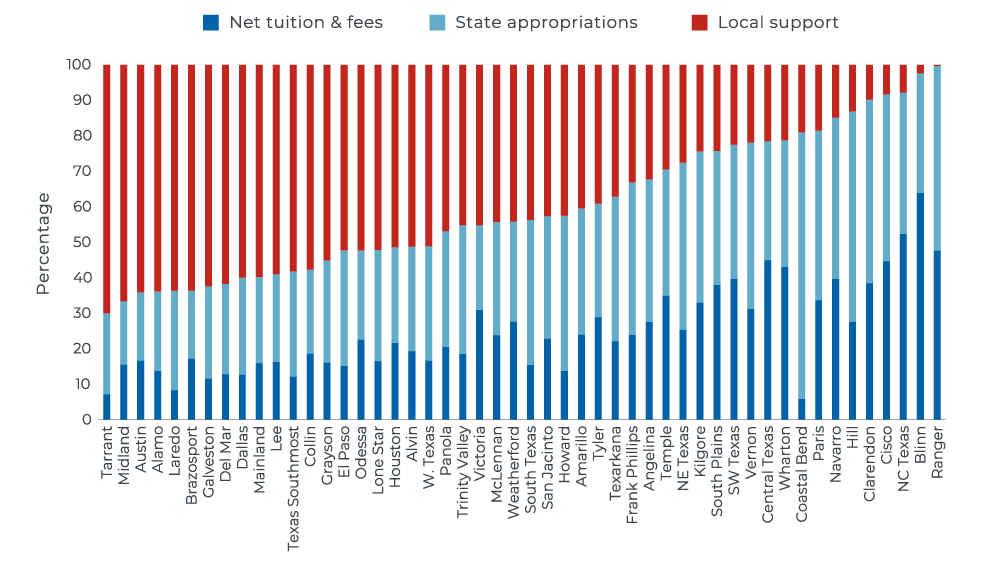

Unlike with K–12 education, where Texas law compensates for the discrepant property values that drive school funding, there have been few efforts to level the playing field for community colleges, leaving some schools amply endowed and others struggling to balance their budgets by raising the prices they charge students (Figure 1).[17] Adding to the problem, one-third of Texans live outside a community college taxing district—they don’t pay taxes to support the school expected to serve them—putting these colleges even further behind.[18]

SOURCE: Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

Locally elected boards that govern Texas community colleges also vary widely, exercising considerable discretion, including, at most schools, over the hiring and firing of faculty and administrators. “Each of these institutions is truly a creature of its region,” explains Sheri Ranis, THECB director of workforce education. “The towns or counties they’re serving, the political leadership that drives them, the predominant industries in their part of the state and, most important, labor market trends—all of that is different in every service area.”[19]

The payoff for colleges that make this decentralization work is unusually close relationships with regional employers. Employers play a critical role in workforce education, partnering with colleges to ensure students are learning skills in demand in the workplace. But many community colleges nationwide struggle to form relationships with local firms, or they maintain only casual, perfunctory ties, often by means of an advisory committee that meets just once or twice a year.

Texas colleges stand out for the depth and strength of their employer partnerships, and educators across the system attribute this success to local control.[20] “It’s in the DNA,” says Jacob Fraire, former president of the Texas Association of Community Colleges. “Most of the members of the local governing boards are either employers or workplace managers or leaders of a local employer group. That’s who selects and appoints the presidents who run the colleges.”[21]

But in this realm too, many Texas schools lag behind. Colleges with more ample resources are better positioned to build relationships with local companies. They can hire staff for that purpose and devote funds to outreach. As a result, a handful of Texas community colleges lead the nation in high-touch collaboration with employers, while others struggle to keep up.[22]

On the other side of Texas’ unique federalist balance is the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board—a group appointed by the governor that sits atop a large, relatively well-staffed state agency. The board provides guidance on higher education strategy, community college academic standards and higher education data collection. It also makes recommendations to the Legislature about higher education funding—both institutional funding and student financial aid.

Staff emphasize that the agency’s role is “coordination,” not governance. Campus-level administrators sometimes grumble about the relationship, with some arguing that the board is too controlling and others noting that they don’t get enough support. THECB leadership says it sees its role as supporting the colleges, and the board makes every effort to ensure its recommendations are consensual.

Some of the tools at the board’s disposal deliver more leverage than others. State formula funding has shrunk in recent years and now accounts for just one-quarter of college revenue, diminishing the state’s influence at the local level.[23]

But the coordinating board strives to support colleges in other ways, including with data and data sharing. Among its goals, according to board leadership, is leveraging the state’s higher education data collection and analysis to help individual schools make better decisions, including about workforce issues. Educators can ask and answer questions about which jobs are in high demand in which regions, and which college programs are most effective in best preparing students for the labor market.

“Our aim is to get behind the innovators and help move the others along,” higher education commissioner Keller explains, “and one of the best ways to do this is with data—helping colleges track and improve the outcomes of their programs.”[24]

Yet another influential tool is a common course numbering system—a statewide course catalog standardizing the programs offered across all 54 community colleges. Courses fall into one of two buckets, academic courses and technical courses, each with a separate online catalog, or “manual.” Each of the 3,651 listings in the Workforce Education Course Manual (WECM) includes a course description, a prescribed set of learning outcomes, guidance on how many hours instruction should take and a funding code. Only courses listed in the manual receive state funding.

This allows the board to set guidelines for content and quality without imposing a straitjacket. Schools are free to offer programs not included in the manual, but those courses receive no state funding. A dedicated statewide advisory committee regularly scrubs the list to ensure job-focused programs are aligned with local labor needs. Importantly for colleges that rely heavily on nondegree programs—generally shorter and more flexible than traditional courses—to prepare students for the workforce, the WECM opens the door to recognition andfunding for job-focused noncredit learning.