II. How Texas colleges compare with those in other states

As different as the state context may be, in many ways, Texas community colleges resemble community colleges everywhere—with the same potential to emerge as a premier provider of job-focused education, but also the same challenges, internal and external.

A recent survey of community colleges by the nonprofit Opportunity America provides a body of evidence to draw upon when comparing Texas community colleges with those in other states, assessing the strengths and challenges Texas faces as it attempts to elevate career education.[25]

The many missions of community colleges

Community colleges are many things to many kinds of learners; there is no such thing as a typical two-year college student.

A first, important divide separates students focused on workforce skills from those seeking a traditional academic education. Many students, particularly conventional college-age students, see community college as a stepping stone to a bachelor’s degree, a relatively accessible, low-cost way to acquire the first half of a four-year education. Other learners, sometimes but not always older, are looking to learn new skills that will enhance their position in the labor market.

This isn’t always a bright line. Some academic credentials are technical—degrees in health care or IT, for example—and they may lead directly to a job or to additional higher education. Clouding the picture further are students with no interest in academic credentials who enroll in nondegree-granting noncredit or continuing education programs, some of them job-focused.

Financed and administered separately from the rest of the college, noncredit programs are often shorter than a semester and come with no additional academic requirements—no English, math or electives. Learners don’t enroll in the college, only in the courses that interest them. Programs are often offered on a compressed schedule designed for older learners and those seeking to return quickly to the labor market.

Both the credit and noncredit sides of the college generally offer workforce education. What’s different in many states is the length and depth of courses. In Texas, the WECM helps ensure parity. Credit and noncredit educators seeking to align with the manual aim to produce the same learning outcomes—the content specified in WECM course descriptions. The manual also ensures equal funding for comparable credit and noncredit offerings, something rarely seen in other states.

Noncredit programs hold a distinct advantage when providing workforce education. Unlike slow-moving academic departments, which often need up to two years to obtain approval for a new course, noncredit departments can launch programs without consulting accreditors or academic faculty committees. This more relaxed oversight leaves room for variation in program quality. But it also allows noncredit educators to respond in real time to the changing needs of employers and job seekers, a unique flexibility that makes continuing education ideally suited to deliver fast, job-focused upskilling and reskilling.[26]

Not all noncredit programs are job centered. Some focus on remedial education, adult literacy, English as second language and learners’ personal interests, such as French cooking and photography. But the changing economy is driving a new emphasis nationwide on noncredit workforce education—short, streamlined, skills-centered programs intended for students in a hurry to switch jobs or land a quick promotion.

Noncredit education is sometimes called the “hidden college,” and with good reason. As a practical matter, the federal government provides no funding for noncredit education and collects no data on noncredit programs or students. And even states such as Texas that make a priority of data collection rarely track noncredit courses as thoroughly as credit offerings.

Yet according to Opportunity America’s national scan of community college workforce education, noncredit programs generate roughly one-third of the nation’s 10.5 million two-year enrollments, some 3.7 million learners who attend college under the national radar.

What’s the mix of missions at Texas community colleges?

In Texas, as in many states, community colleges struggle to balance their two principal missions, preparing students for the workplace and for future higher education.

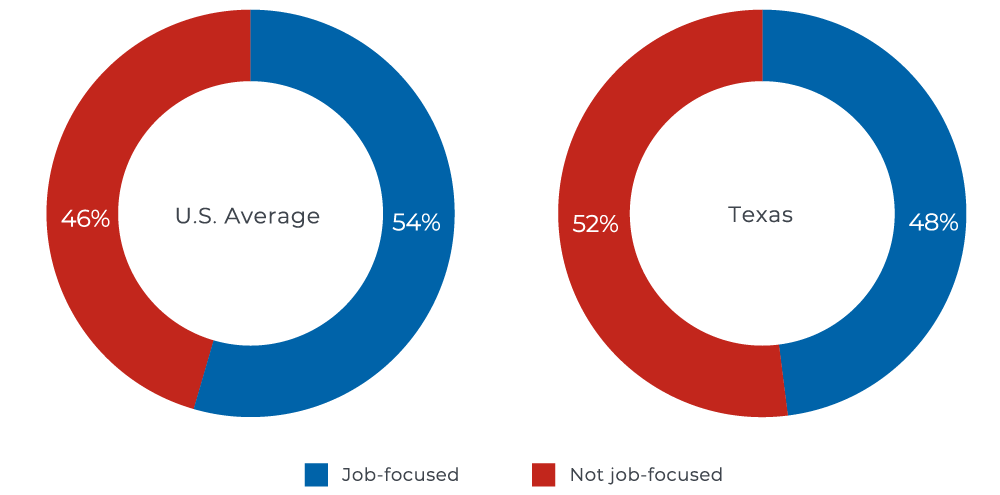

Change-minded Texans seeking to enhance workforce education inherit a system slightly tilted toward academic preparation. At community colleges nationwide, according to the Opportunity America survey, the mix of programs skews in favor of job-focused instruction. Students in career-oriented programs account for 54 percent of enrollments; those studying traditional academic subjects account for 46 percent. In Texas, in contrast, the ratio favors academic programs, 52 percent to 48 percent in vocational programs (Figure 2).

Community college enrollment in job-focused vs. non-job-focused programs

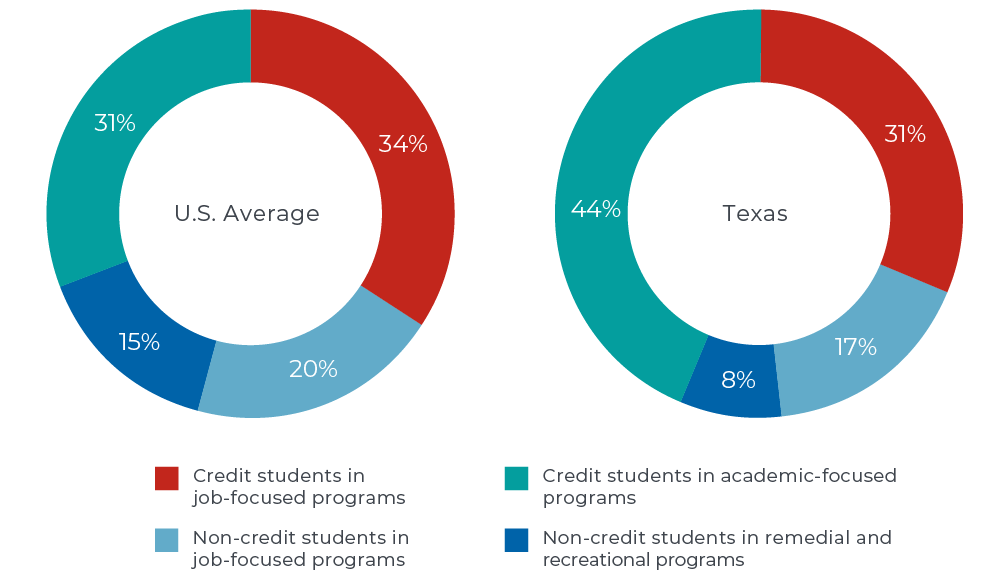

But this simple accounting of job-focused and non-job-focused instruction belies a more complicated story that includes the divide between credit and noncredit programming. The Opportunity America community college survey rounded out its findings on noncredit education with data on credit programs from the National Student Clearinghouse to paint a holistic picture of job-focused and non-job-focused offerings at Texas community colleges (Figure 3).

Enrollment by credit and job-focused programs

What the combined findings show: Texas’ allocation stands out for three reasons.

First, consistent with the system’s overall skew toward academic education, Texas community colleges serve more credit-seeking academic students than many other schools nationwide. At the Texas colleges that participated in the survey, 44 percent of students are focused on traditional academic college credentials, compared with a national average of 31 percent.[27]

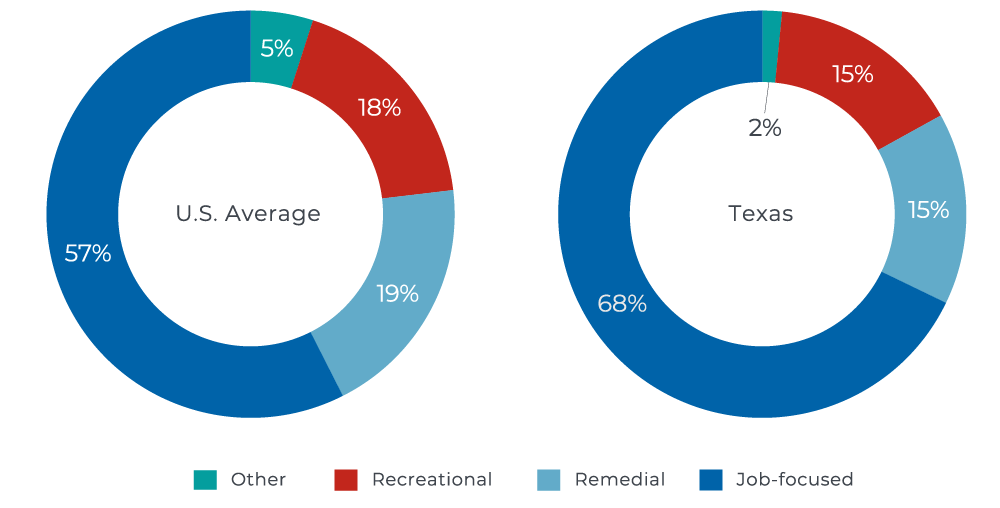

Second, noncredit education accounts for a smaller share of Texas enrollments, 25 percent in Texas compared with 35 percent nationwide. And yet, a third discrepancy, the mix of noncredit programming, is notably different in Texas than nationwide. Among Texas’ noncredit programs, a significantly larger share is devoted to workforce education (Figure 4).

Community college noncredit enrollment by type of program

Nationally, on average, 57 percent of noncredit enrollments are job-focused, with the rest split almost evenly between remedial and recreational courses. In Texas, according to the Opportunity America survey, 68 percent of noncredit education is job-focused, while 15 percent is remedial and just 15 percent recreational.

This suggests that Texas community colleges are taking advantage of the noncredit division’s signature strength: its unique ability to provide just-in-time job training aligned with local labor market demand.

Wide discrepancies among Texas community colleges and the sample size—32 of the state’s two-year institutions responded to the survey—make it difficult to generalize from these data. But the numbers suggest that unlike some states that prioritize one mission—either academic learning or workforce education—most Texas schools strive to do both.

Texas community and technical colleges serve as stepping stones to higher education for less-advantaged, often minority students with limited access to four-year colleges and universities. But they also maintain a robust capacity for workforce education and training. What’s unclear from these data: how Texas colleges balance what are often felt to be competing aims and how well they fulfillboth missions.

Credit and noncredit student outcomes

In Texas, as nationwide, despite years of attention to improving student outcomes, community college graduation and transfer rates remain stubbornly disappointing. According to state higher education data, only 34 percent of full-time Texas community college students graduate within four years of enrolling in a two-year program, and just 25 percent transfer to a four-year college or university.[28]

Both numbers are on a par with national outcomes.[29] Nationwide, 74 percent of traditional college-age students arrive at community college expecting to transfer to a four-year institution and earn a bachelor’s degree, but only 13 percent ultimately succeed.[30]

In Texas, as elsewhere, career-focused credit programs appear to do a somewhat better job of producing the results they aim for. According to Texas data, 90 percent of students who complete what the state calls “technical” community college programs are either employed or enrolled in further education and training the year following graduation.[31] What isn’t known: Do graduates find jobs in their fields of study, and do they earn more than they would have earned if they had not attended college?

Even less is known about employment outcomes on the noncredit side of the house. Texas collects more complete data on noncredit workforce education than many other states. The higher education coordinating board is moving to produce and publish more ample information about graduates’ jobs and wages for credit and noncredit students. And a 2022 University of Michigan analysis of noncredit programs in Texas and four other states suggests modest wage gains for Texas noncredit workforce students.[32] But we know much more about credit students than noncredit students and more about academic attainment than workforce outcomes—jobs and wages.

In Texas, as nationwide, what information we have— regarding academic, workforce, credit and noncredit outcomes—underscores the urgency of the questions today’s reformers are posing to the state. How do Texas community colleges define their mission, and do they have the balance right?

The choice is not either/or. Texas educators and policymakers, like educators and policymakers everywhere, agree that community colleges must continue to pursue both missions—academic attainment and workforce education. The difficult question: Given these mixed results and the changing economic needs of the state, just what should the balance be?

“We need to dramatically expand what we do around workforce education,” says higher education commissioner Keller. “This means fundamentally changing the financial incentives around workforce programs and breaking down the barriers between credit and noncredit education.”[33]

|

Blurring the line between credit and noncredit to respond to employers

It was a great opportunity but also a challenge for Austin Community College (ACC). The economy was booming. The IT companies ramping up in the region were in dire need of technical workers. But many firms had eliminated the internal training programs they once relied on to onboard employees. ACC was ideally positioned to step in as a contract training provider, and it initiated a conversation with executives at Samsung.

Samsung wanted a program up and running fast. But launching a course on the degree-granting credit side of the college could take months or even years. The school would need approval from faculty and a regional accreditor. The answer was to incubate the program on the college’s noncredit side, which does not need faculty or accreditor approval for new offerings. But that division wasn’t prepared to partner with a world-class corporation. It lacked equipment, had no capacity to track students and offered mostly personal-interest courses, with no option for learners seeking more education to make a transition to a degree-granting program. ACC’s first step was to secure a Skills Development Fund grant from the Texas Workforce Commission. Designed to help Texas firms upgrade their workers’ skills, but payable only to a partnering community college, the grant could fund needed capacity building in the ACC noncredit division. The new Samsung training program launched in late 2014. The college used grant funding to purchase equipment and worked with Samsung to develop a curriculum. Instruction was offered at the company for full-time employees only—some long-tenured incumbents and others just hired and in need of entry-level training. Classes were scheduled around workers’ shifts. Samsung committed to paying trainees a living wage and keeping them on its payroll for at least a month after the training ended. Both company and college were pleased with the results, but both also saw that this was just the start of what they could do together. In addition to internal training for incumbents, Samsung needed a regional talent pipeline—a ready supply of manufacturing workers at all skill levels, including some who had completed sophisticated technical training on the credit side of the college. For ACC, this was an opportunity to build out an array of other manufacturing programs, credit and noncredit, open to any student enrolled in the college, not just Samsung’s hand-picked incumbents. The growing partnership with Samsung also drove a critical organizational change at the college, combining short, noncredit manufacturing training and for-credit manufacturing degree programs under one division and one department chair. No more than a dozen colleges nationwide have blurred the line between credit and noncredit in this way. It is an unthinkable step for many faculty who see an unbridgeable divide between what they view as credit-bearing “education” and noncredit “training.” But it took off in Austin. “Employers loved it,” recalls the new department chair, Laura Marmolejo.[34] “Whatever they needed, on the credit or noncredit side, they could come to me and I spoke for the college—one voice.” Even more important, the consolidation made it possible for ACC to design pathways for students that led from entry-level noncredit training up through an associate degree. “Very few colleges build for crossover between credit and noncredit education,” explains Garrett Groves, ACC vice chancellor of strategic initiatives.[35] “Credit and noncredit instructors think they’re teaching different student bodies and that programs don’t have to align. We see it differently, and we build for it. It’s baked into the way we design our noncredit programs.” The key is overlapping course content. The training provided to Samsung incumbents is a module of a longer, credit-bearing manufacturing course. Students who want to transition from noncredit to credit education accumulate modules they can leverage for college credit if they later enroll at ACC, saving time and money as they work toward a degree. After years of partnering with Samsung, ACC now offers many kinds of manufacturing instruction. Programs run the gamut from noncredit incumbent training at the company, entry-level noncredit courses at the college, a bridge program to help learners making the transition from noncredit to credit, credit-bearing certificate and degree programs, and a credit-bearing earn-and-learn apprenticeship program. The next step: a bachelor’s degree program in manufacturing and applied technology. Samsung partners with the college on virtually all these initiatives, including the apprenticeship program. It’s a model of educator–employer collaboration that ACC is now replicating with other firms in the region, including the college’s newest partner, Tesla. But the most important payoff is for learners. “We’re finally at the point,” Marmolejo says, “where we can say to students, ‘We have an option for you, no matter your situation or your interest or your comfort zone.’”  |

Who attends community college?

Another important set of questions about Texas community colleges centers on students. Does the face of the student body mirror the population in the region? Does the student profile skew older or younger than the national average? And if it skews one way or other, what, if any, action is needed to ensure that all potential students have access to the education they seek?

Gender

Roughly 60 percent of credit-eligible Texas community college students are women, mirroring the national average.[36]

The gender mix among noncredit workforce students is more evenly balanced: In Texas and nationwide, among those who report their gender, about half are men and half women.

Age

One of the most significant differences between community colleges and four-year schools is the wide spectrum of ages served by two-year institutions. Unlike four-year colleges, where 90 percent of students are traditional college age, community colleges touch a much broader swath of the population, older and younger.[37]

At the younger end of the spectrum, in Texas, as nationwide, the last decade or so has seen a push to blur the line between high school and college, particularly community college. Educators seeking to enhance the high school experience and increase the chances that high school students will enroll in college are finding ways to bridge what for many students is a perilous gap. Many are allowing high school students to enroll in college-level courses or providing college-level instruction at the high school.

This innovation varies somewhat from state to state and goes by a variety of names: dual credit, dual enrollment and early college high school, among others. Texas has been at the forefront of the experiment. According to the coordinating board, over the last decade, almost all the net growth at Texas community colleges was driven by dual enrollment.[38] In 2020, 25 percent of credit-seeking students were in dual enrollment programs, and the credit-seeking student age profile skewed predictably young.[39] Nearly one-quarter of credit enrollments were less than 18 years old.[40]

At the other end of the spectrum, in Texas, as elsewhere, community colleges serve a growing number of midcareer adults. Workers now change careers more frequently than in the past, a trend amplified by the pandemic. Workers displaced by automation and other changes often return to college to learn new skills, either for a new job or a new industry. And two-year colleges everywhere are struggling to adjust, finding ways to accommodate older learners’ goals, schedules and learning styles.

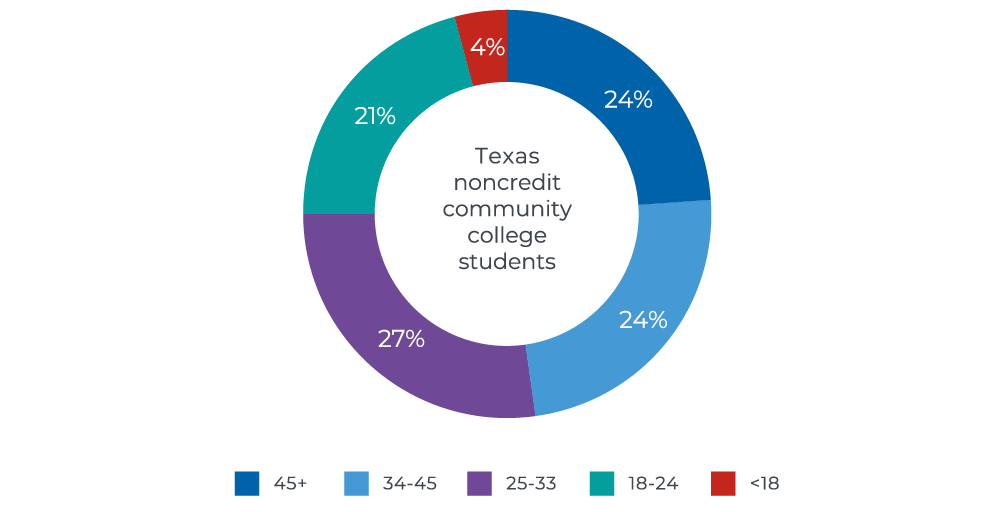

In Texas, as elsewhere, this shift shows up most clearly in community college noncredit enrollments. According to Texas data, just 13 percent of credit-seeking students at two-year institutions are over 30.[41]

But according to the Opportunity America survey, 75 percent of noncredit learners are 25 or older, with nearly half over 35 and many in their 40s and older (Figure 5).

Noncredit students in job-focused programs by age

Both of these skews, young and old, have implications for policymakers charting a future for Texas community colleges, and they point in somewhat different directions, suggesting some hard choices ahead.

The overwhelming majority of dual-credit students take traditional academic courses. Among other reasons, it’s much cheaper to offer classes in traditional subjects such as social studies and college algebra than practical hands-on instruction in welding or phlebotomy, and the state offers few financial incentives to develop job-focused dual-credit programs. But just the opposite is true at the other end of the age spectrum: Midcareer adult demand skews sharply in favor of job-focused upskilling and reskilling.

In theory, there’s no reason Texas community colleges can’t do both things—some mix of academic and skills-centered programs for dual-credit students and more workforce education for midcareer adults. But many colleges struggle to get the balance right, and it may require an adjustment in the state financial incentives that drive decisions about what programs to offer.

Two reforms stand out as the state seeks to align community college outcomes more closely with the labor needs of the changing economy. The first is offering more job-focused dual-credit programs that will put high school students on a path to job-focused college instruction. The second is strengthening noncredit divisions to better serve midcareer learners, elevating continuing education and integrating it more closely into the life of the college.

Race and ethnicity

Of particular interest in Texas is how well community colleges serve students of color, principally the state’s fastest-growing demographic, Hispanics. In this realm too, data are incomplete. We know more about credit students than noncredit students and more about academic attainment than workforce outcomes. New information is coming soon from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, but existing data allow us to piece together a preliminary picture and anticipate the challenges that lie ahead.

Texas grew more rapidly than almost any other state between 2010 and 2020—a blistering 16 percent population increase.[42] Hispanics accounted for 50 percent of that growth. More generally, people of color, including Hispanic, Black and Asian American residents, represented 95 percent of the increase.[43] This growth is projected to continue in the years ahead, with Hispanic residents expected to emerge as the state’s largest constituency within a decade.[44]

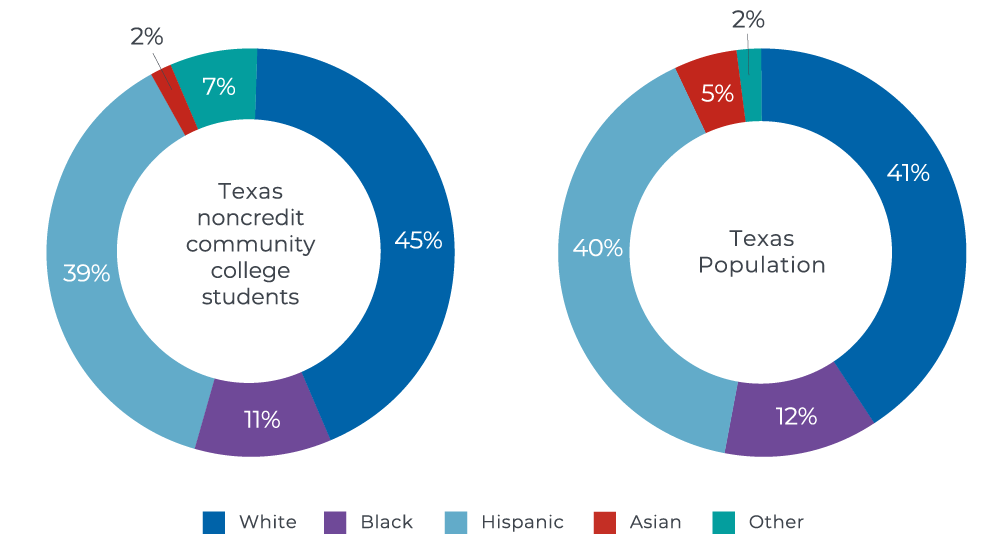

Growing numbers of Hispanic students look to community colleges for both academic and workforce education. Credit-eligible enrollments skew heavily Hispanic: 50 percent of credit-seeking students are of Hispanic heritage compared with 40 percent of the state population.[45] Noncredit enrollments are also robust, roughly equivalent to the Hispanic share of the population (Figure 6).[46]

Noncredit enrollment and population by race and ethnicity

Black enrollments largely mirror the Black share of the population—11 percent of credit enrollments, 11 percent of noncredit enrollments and 12 percent of the state population.[47]

Some observers will see this as cause for concern: Why are so many students of color attending community colleges rather than four-year schools? In fact, for many of these learners, the choice may not be between two types of college. More likely, it’s whether they attend college at all. And by that measure, schools that skew heavily minority, whether on the academic or workforce side of the house, can be engines of opportunity and upward mobility.

Where Texas community colleges still have work to do: bringing Hispanic and Black completion and credential attainment into line with non-Hispanic white achievement.

Looking at educational attainment by all Texas adults 25 and older, significantly more non-Hispanic white students than Hispanic students—71 percent versus 40 percent—have some college education and often an academic degree, whether an associate, bachelor’s, graduate or professional degree.[48] Black attainment is more encouraging—62 percent—but still below that of non-Hispanic white students.

Looking just at adults whose education prepares them for a middle-tier job—those with some college or an associate degree—Hispanic attainment falls below that of the other groups at 24 percent, compared with 36 percent for Black and 32 percent for non-Hispanic white attainment.[49]

Recent numbers look somewhat better. Minority student credential attainment—the share of learners who earned degrees and academic certificates in 2020—seems roughly on par with that of other groups in Texas.

According to the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, Hispanic students accounted for 46 percent of community college enrollment in 2020 and 45 percent of certificates and degrees awarded at two-year schools.[50] Black students accounted for 12 percent of enrollments and 12 percent of credentials earned.

Hispanic transfer rates were less encouraging. Just 23 percent of Hispanic students who enrolled in community college in 2014 had transferred to a four-year college or university within six years, compared with 30 percent of non-Hispanic white students and 45 percent of Asian American students.[51]

The higher education coordinating board is expected to release new, more granular data in coming months on credential attainment and employment outcomes for Black, Hispanic and other students. Of particular interest apart from academic awards—degrees and certificates—are nondegree alternative credentials with value in the labor market, including competency-based certifications developed and awarded by industry groups. This information will be essential for educators working to close the Hispanic education-attainment gap, but it’s only the start of what’s needed. Improving outcomes for underrepresented groups is an urgent issue for the state.