Federal support keeps state budgets (including Texas’) healthy amid tumult from COVID-19-induced economic ills

The nation suffered a historic, broad-based two-month economic decline—beginning in late February 2020—across all regions. A variety of indicators went into a freefall from which they have yet to fully recover. It seemed likely that many of the jobs and firms lost to the impacts of COVID-19 would never return.

Many states began planning for fiscal disaster. With fewer people working and fewer firms in business, there would be less income and revenue coming in, and thus, less spending going out. Forecasts pointed to impending fiscal shortfalls for 2020–21 that would be comparable to, or even surpass, those experienced during the Great Recession, from December 2007 to June 2009.

These forecasts largely didn’t pan out. Instead, many states find themselves awash in revenue, expanding services and paying down debt. New Jersey met its yearly pension-funding obligations for the first time since the 1990s; California is disbursing cash to two-thirds of its residents; and even perennially cash-strapped Illinois received a credit Federal Support Keeps State Budgets (Including Texas) Healthy amid Tumult from COVID-19-Induced Economic Ills rating upgrade for the first time since 2000. Illinois also ended the 2021 fiscal year with a $2 billion surplus.

How were state budgets able to sustain themselves so well during this recession?

In broad terms, the answer is twofold. First, state tax revenue held up better than expected, especially in areas where business-cycle fluctuations normally affect receipts. Second, the federal government hugely increased its spending during the recession, providing an unprecedented amount of grants and loans to prop up state budgets, as well as direct aid to individuals and businesses.

Funding State Budgets

Typically, recessions are accompanied by declines in personal income as people lose their jobs or find themselves< working fewer hours.

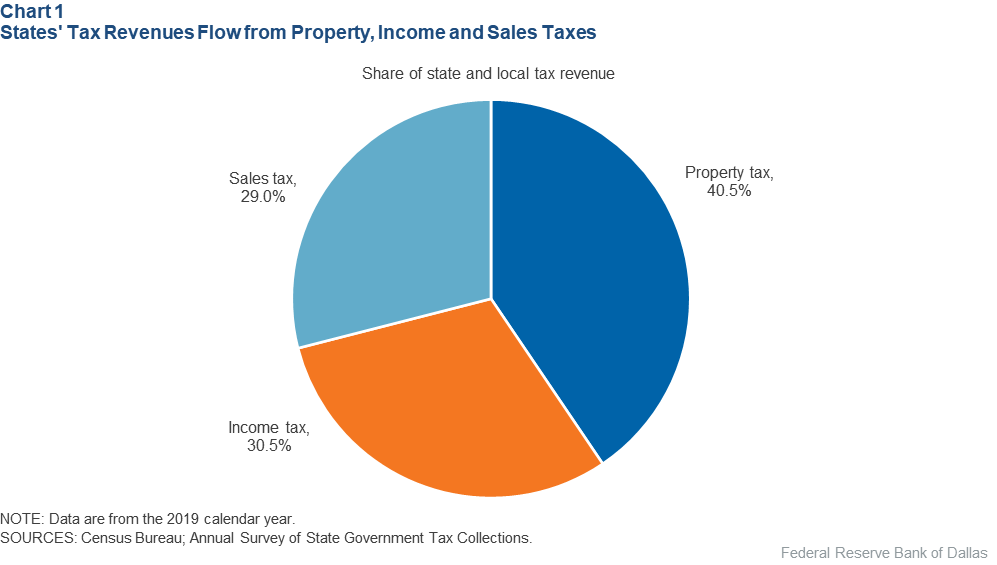

These reductions in personal income affect state tax revenue—but not in a uniform way. In the aggregate, state and local governments raise revenue through a combination of sales, income and property taxes. While revenue shares of each of these can differ sharply, the sum across states is roughly in equal proportion (Chart 1). While not every state chooses to emphasize revenue diversity, those that do are less dependent on any single revenue source.

A broad mix of taxation also helps insulate states and localities from macroeconomic developments. Real estate busts can depress home values at double-digit rates, affecting property tax revenue. Heightened uncertainty can cause people to save more and consume less, reducing sales tax revenue. And during economic downturns, lost jobs, wage declines and fewer hours worked contribute to diminished income taxes.

Risking Lower Revenues

However, while all of these tax instruments pose risks at different times, they are not equally volatile as an economy enters recession. Real estate boom-bust cycles can sometimes occur during expansions, and it is possible for home prices to keep rising in a recession, as they did in 2020.

Despite early forecasts that people would abandon central cities in the wake of COVID-19 and work remotely, property values continued rising rapidly in urban cores, though the rate of increase was even greater in suburbs/exurbs.[1]

Still, real estate prices can be highly volatile, especially in metro areas where natural barriers (such as mountains) or zoning laws constrain construction or, conversely, where construction occurs at an especially rapid pace, leading to speculative supply bubbles. But these situations don’t pose a particular vulnerability during recession.

Income tax revenue on the other hand is much more vulnerable to recession because incomes tend to take a large hit during a recession. As businesses fail, people lose their jobs or are forced to work fewer hours or for lower wages, reducing income earned and income taxes paid.

The more severe a recession, the more severe the income drop, with especially large declines triggering yawning budget shortfalls in states such as California and Illinois that rely on income taxes for a disproportionate share of revenue.

Sales taxes typically occupy a middle ground, tied to the business cycle but not especially vulnerable to it. Numerous economic studies have found that consumption is more stable than income.

The intuitive reason for this is that when someone loses their job and their income falls, they must still spend on necessities such as food, clothing and shelter. Often this is done by drawing on savings, borrowing from friends or family members and running up credit card debt. This, in turn, tempers any surge in consumption that might accompany an economic recovery when jobs are regained.[2]

Funding for States

One important implication is that income-tax-reliant states will be significantly more vulnerable to business-cycle fluctuations. On the plus side, such states may experience massive budget surpluses during good economic times that can be used to expand government services for vulnerable populations. On the other hand, these states are nearly assured of large budget shortfalls during recessions.

This matters because of the constitutional limitations under which states and localities generally operate. When individuals (or the federal government) spend more than they receive, they can cover the resulting shortfall with debt.

However, states and localities are generally required to balance their budgets and cannot deficit-spend. As a result, government leaders often must cut budgets or enact tax increases during a recession.

The discomfort of such fiscal adjustments depends on the fiscal mix on which a state relies for its revenue. At one extreme are the seven states—including Texas—that impose no income tax and are, thus, least vulnerable to business-cycle fluctuations. At the other extreme is a group of states—including California, New Jersey and Illinois— that rely disproportionately on income-tax revenue to fund operations.

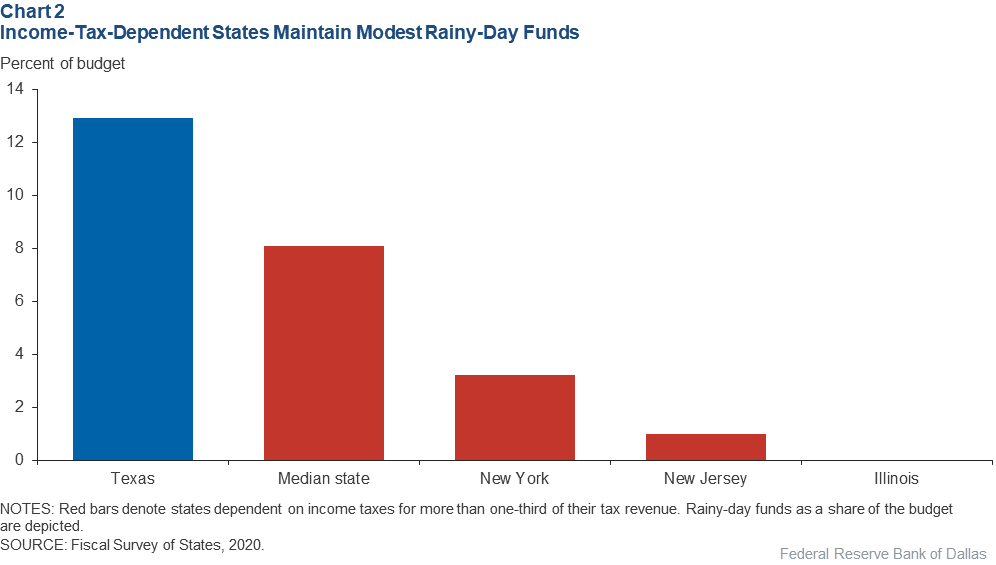

The good news is that because this vulnerability to recession can be assessed well in advance of when a downturn begins, states that choose to rely on business-cycle-dependent revenue sources can compensate by carrying above-average rainy-day fund balances.[3]

Often, they fail to fully deploy such measures. In the year before COVID-19, New York’s rainy-day fund balance of 3.2 percent of its budget was less than half the national average of 8.1 percent (Chart 2). Yet even that was triple New Jersey’s 1.0 percent balance and infinitely larger than Illinois’ 0.0 percent.

This combination of high business-cycle vulnerability and a low rainy-day fund balance nearly guarantees tough times when recession strikes.

Texas, on the other hand, carried an above-average rainy-day fund balance of 12.9 percent of its budget, though there is no state income tax. This stems in part from its large oil and gas production, a sector that is a major contributor to the fund and is notoriously volatile.[4]

COVID-19’s Unusual Impact

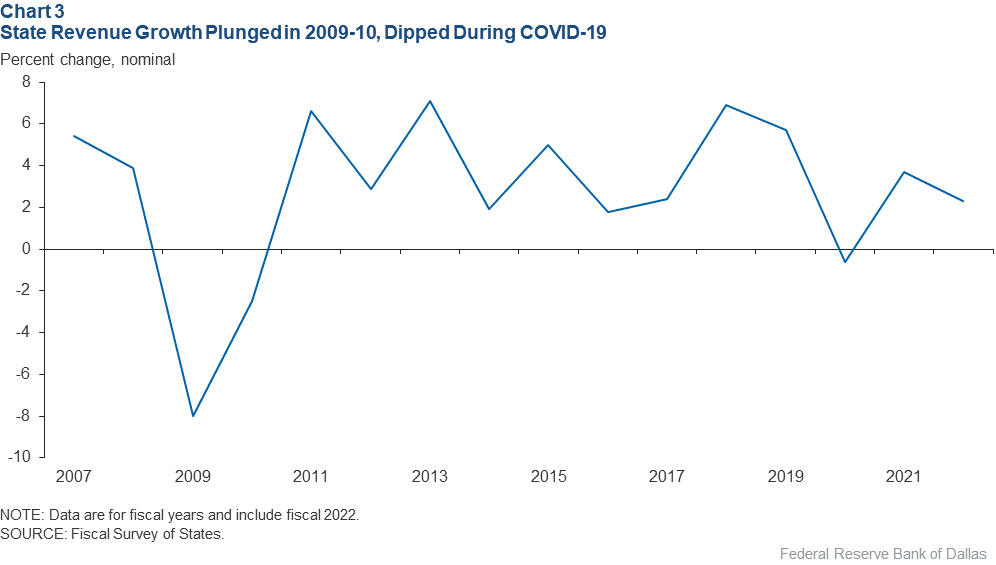

As people lost their jobs and firms ceased operations during the last major downturn, the Great Recession, state budgets faltered. State revenue, after rising 3.9 percent in 2008—the first full year of the recession—fell 8 percent in 2009 and an additional 2.5 percent in 2010, necessitating significant cuts to social services at precisely the time they were most needed (Chart 3).

Shaped by this experience, states expected a similarly severe budget crunch in the COVID-19 era. But something different happened. While revenue in 40 of the nation’s 50 states didn’t meet pre-COVID-19 expectations for fiscal 2020–21, it shrank by a relatively modest 0.6 percent in 2020 and actually grew 3.7 percent in 2021.[5] State revenue is expected to expand an additional 2.3 percent in 2022, according to recent estimates.

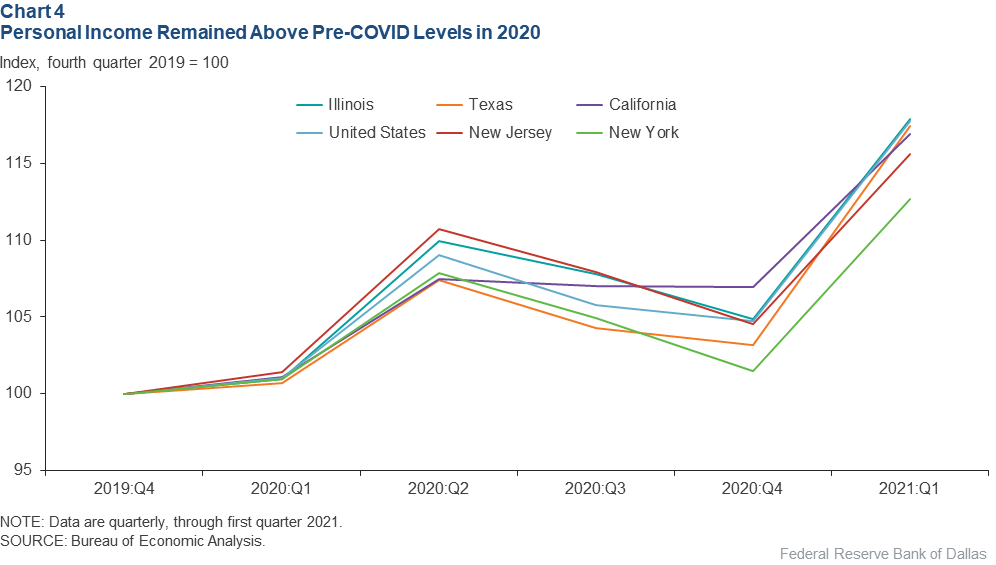

To be sure, there are many differences between the Great Recession and COVID-19 eras. Chief among them is what has happened to personal income. In 2009, for example, personal income dropped in 49 of the 50 states.

During second quarter 2020, personal income for the U.S as a whole soared 8 percent, even as COVID-19 knocked millions of Americans out of work and reduced work hours for millions more (Chart 4). Personal income remained above prepandemic levels for the rest of the year and into first quarter 2021.

This was also true for large states—Texas, New York and even Illinois. By first quarter 2021, personal income in Texas was 17.4 percent above where it had been in fourth quarter 2019. If this remarkable performance were due solely to factors such as accommodative state policy toward business, housing availability and a relatively young demographic, then one might expect other states that lack some of those characteristics to experience slower personal income growth.

Yet other large states experienced broadly similar personal income patterns from the onset of COVID-19 through first quarter 2021—exceeding fourth quarter 2019 levels by 12.7 to 17.9 percent.

This behavior of personal income ensured that even income-tax-reliant states would not face sizable fiscal shortfalls in 2021–22 despite beginning the crisis with what were in many cases notably low rainy-day fund balances.

Federal Fiscal Support

Personal income held up because of a historically unprecedented (in peacetime) federal spending increase. Among the many measures taken by the federal government to bolster personal income were direct stimulus payments to individuals and augmented unemployment insurance benefits for people who lost their jobs. In some cases, the program provided a higher weekly stipend than recipients’ past wages.[6]

There were also grants and loans to firms through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), primarily intended to ensure that businesses could meet payrolls.[7] This support came through an array of legislative action in 2020, including the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act (March 6), the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (March 18), the CARES Act (March 27), a liberalization of the PPP (April 24), the Consolidated Appropriations Act (Dec. 21), and in 2021, the American Rescue Plan (March 11). All helped improve state fiscal outlooks by averting layoffs and firm closures.

The federal government also provided sizable direct grants to states such as Texas.[8] While it is not yet known how all of these funds will be spent, Texas’ timely publication of state revenue information illustrates just how substantial these grants have been.

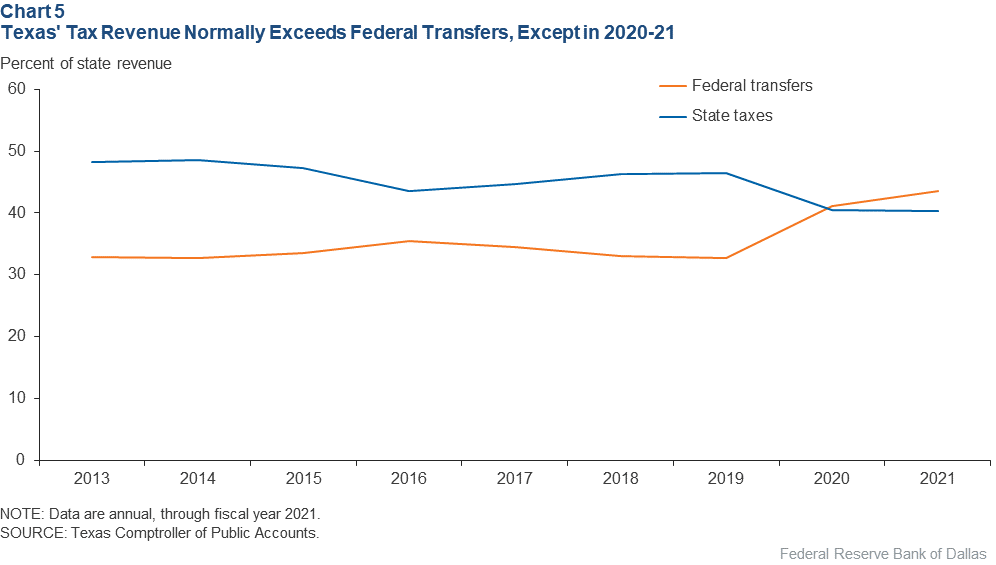

Historically, state taxes (such as the sales tax) provide about half of total Texas revenue compared with one-third from federal transfers (Chart 5).

But the pandemic-era surge in federal support for state budgets boosted federal transfers by about $16 billion in 2020. They have remained elevated in 2021, making the federal government the single largest revenue source for Texas in both years.[9]

Federal transfers accounted for 33 percent of state revenue in 2019, 42 percent in 2020 and 43 percent in 2021.

Future Recession Aid

Will future recessions be addressed with equally stimulative fiscal policy, or will the response follow more conventional lines?

The answer has special resonance for the optimal configuration of state fiscal policy. State sales taxes are more regressive than income taxes but have also historically offered more stability than income taxes because income is so volatile over the course of the business cycle.[10]

To the extent the federal government will now more readily intervene to reduce income volatility, we may see states such as California and New York fare better than they typically would during a recession; however, at least indirectly, such support would likely help states such as Texas, too, by bolstering consumption.

Longer term, the unprecedented peacetime debt accumulated by the federal government in 2020 and 2021 could have consequences. Research has shown that a large and expanding debt load constrains countries’ abilities to handle future crises and risks imposing burdensome repayment obligations—higher taxes—on future generations.

For now, though, federal stimulus appears to have helped keep both personal income and state government budgets growing during difficult economic times.

Notes

- “COVID-19 Fuels Sudden, Surging Demand for Suburban Housing,” by Laila Assanie and Yichen Su, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Fourth Quarter 2020.

- See the Fed’s yearly survey on household economics and decision-making for more on how households respond to financial stress “Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2019—May 2020,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, accessed Aug. 17, 2020.

- “Lingering Energy Bust Depresses, Doesn’t Sink State Budgets,” by Jason Saving, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Fourth Quarter 2016.

- Disagreements over the intended purposes—and legitimate uses—of the rainy-day fund have also played a role in its growth. For more on how these issues have come into play in the COVID-19 era, see “Texas Has Billions in Its Rainy-Day Fund, But Legislators Say They Won’t Use It Until January,” by Clare Proctor, Texas Tribune, May 11, 2020.

- 2020 “Fiscal Survey of States,” National Association of State Budget Officers, accessed Aug. 17, 2021.

- “Pandemic Unemployment Benefits Provided Much-Needed Fiscal Support,” by Anil Kumar, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Fourth Quarter 2020.

- “Small Business Hardships Highlight Relationships with Lenders in COVID-19 Era,” by Wenhua Di, Nathaniel Pattison and Chloe Smith, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Second Quarter 2020. For details on how PPP funds were allocated across states, see “Who Benefited from the Paycheck Protection Program? Our Texas Analysis Offers an Early Look,” by Emily Ryder Perlmeter, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Dallas Fed Communities, Sept. 4, 2020.

- The federal government also made grants on a smaller scale to other government entities such as cities and school districts.

- The various federal income-support programs also likely boosted state revenue by, for example, enabling consumers to make more purchases than they otherwise could. Thus, the chart may understate the impact of federal stimulus on state revenue in the 2020–21 period.

- “Texas Taxes: Who Bears the Burden?” by Jason Saving, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy, Third Quarter 2017.

About the Author

Jason Saving

Saving is a senior economist and director of the Research and Studies function in the Communications and Outreach Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2021/swe2103.