Private forecasters’ COVID-19 global growth outlook takes shape

Private forecasters’ expectations for near-term global growth have dramatically deteriorated since the beginning of March, in part reflecting stringent physical distancing policies and the attendant costs of responding to the spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19).

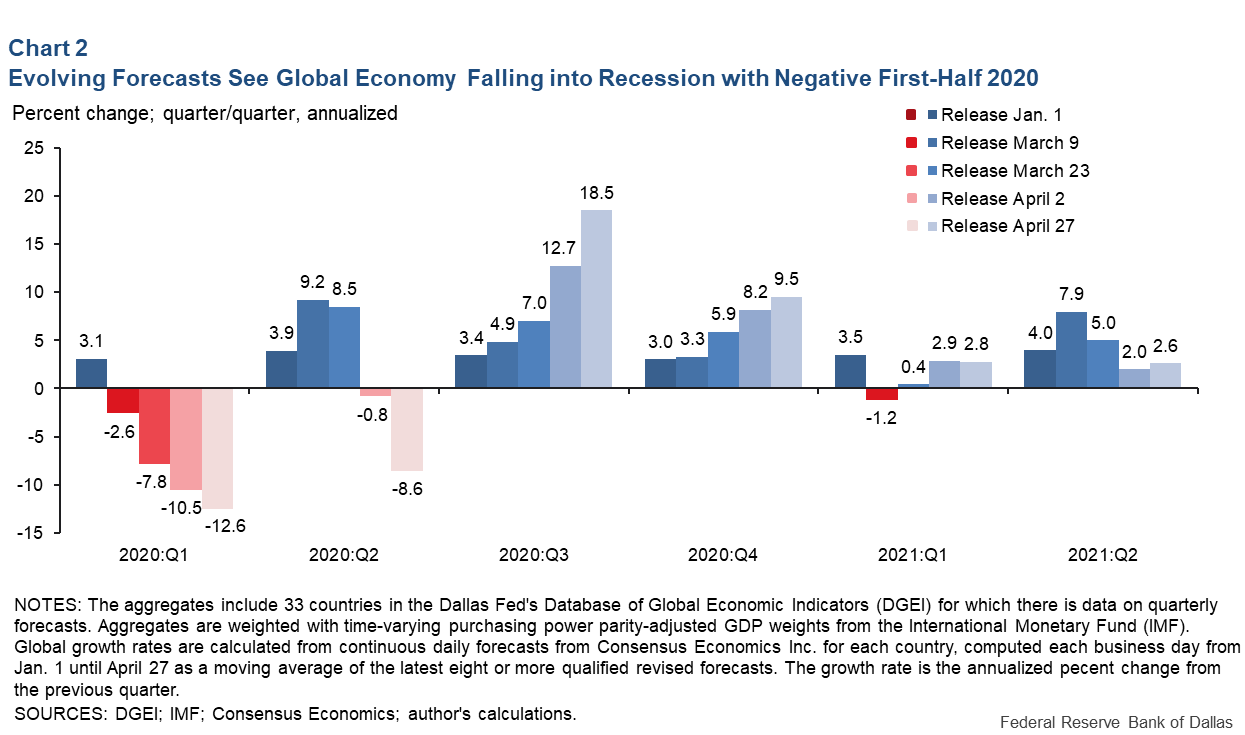

Private forecasters have anticipated since April 2 that the economy would contract for two consecutive quarters, marking a global recession unlike any seen in peacetime. As of April 27, our analysis of forecasters polled by Consensus Economics covering a broad sample of countries indicates that the global economy likely shrank an annualized 12.6 percent in first quarter 2020 relative to fourth quarter 2019 and will weaken a further 8.6 percent in the second quarter.

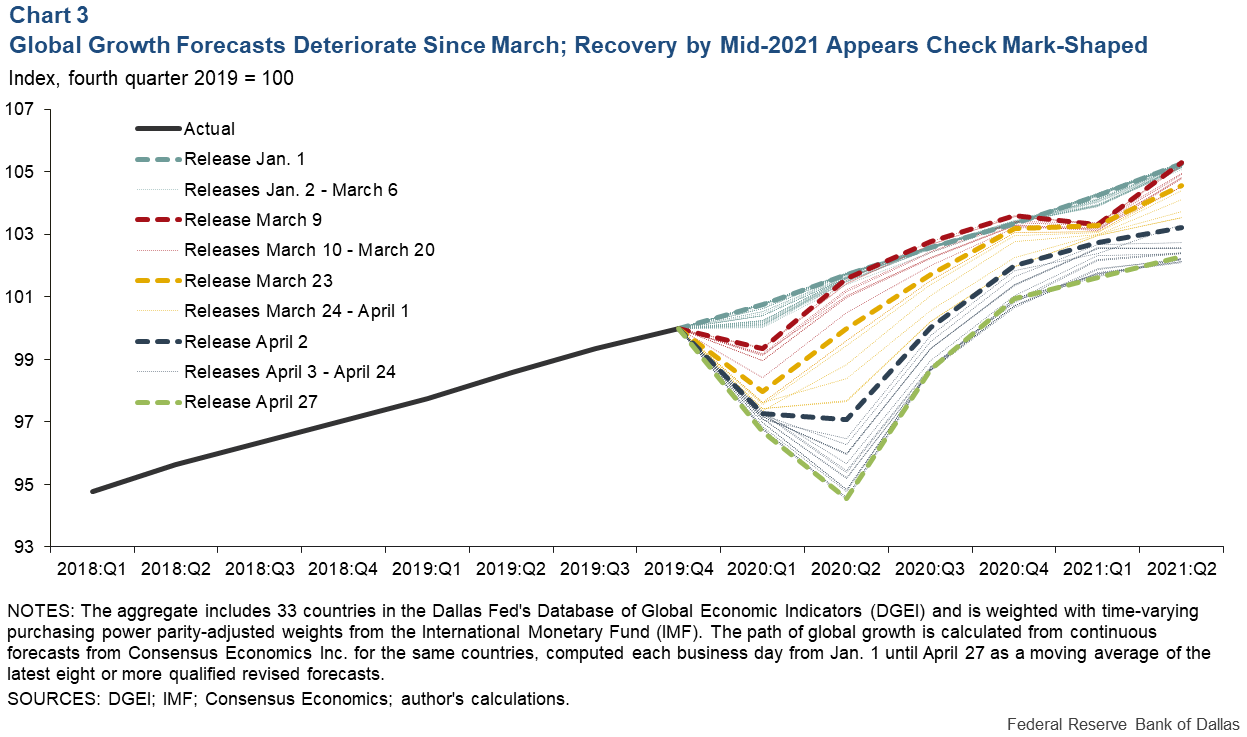

The forecasters’ expectations have coalesced toward a check mark-shaped type of recovery—well below their expectations at the beginning of 2020, with a strong bounce-back in the second half of the year but with less-firm (and more uncertain) prospects beyond that.

Global recession in the making

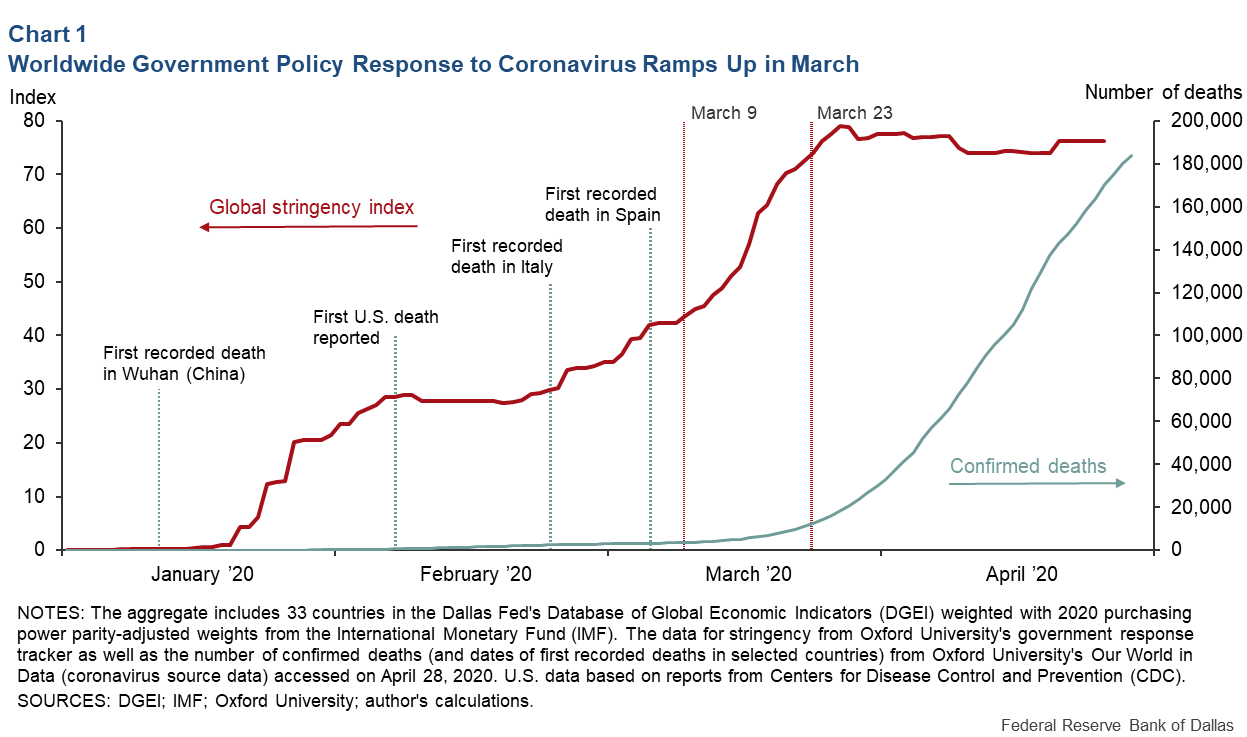

Governments are taking a wide range of measures in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) tracks in real time the extent of such policy reactions to the coronavirus outbreak worldwide.

Chart 1 illustrates the evolution of an aggregate of OxCGRT’s government response stringency indicator and the number of confirmed deaths through the end of April.

The aggregates are based on a subset of the panel of countries in the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas’ Database of Global Economic Indicators (DGEI). The subset is composed of the U.S. and 32 major world economies that have historically strong trade ties with the U.S. These 33 countries accounted for 81.1 percent of world output in 2019, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Country-specific indicators of anti-COVID-19 policy stringency are weighted using the IMF’s annual share of world GDP for each country—expressed in purchasing power parity terms.

Global policy has evolved with awareness following the initial outbreak in Wuhan, China. The first-phase policy response largely centered on containment, with most restrictions aimed at slowing or preventing the spread of COVID-19 outside China. After those actions proved insufficient to prevent the international spread of the virus, isolation (physical distancing, shelter in place and quarantine) was deemed necessary. Additional support strategies—boosting health care systems and fiscal (and monetary) accommodation—also became the norm among many countries by mid-March.

Stringent policy responses in this second phase have had a major macroeconomic impact on the global economy, in part evidenced by a rapid and dramatic deterioration of private forecasters’ near-term outlooks.

The evolution of private forecasts on global growth can be assessed at a high frequency by aggregating Consensus Economics’ continuous economic survey data for the 33-country DGEI subset. Global growth forecasts over six quarters, starting with first quarter 2020, can be aggregated on a daily basis—from Jan. 1 through April 27—based on a moving average of the latest revised forecasts.

Private forecasters’ expectations offer a unique perspective on the near-term global outlook. The firming of global growth heading into 2021 predicted on Jan. 1 remained largely unchanged during the first phase of containment (Chart 2).

March 9 marked a turning point, when Italy’s Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte imposed a nationwide lockdown restricting movement except for narrow work or health reasons. Around that time, private forecasters anticipated a global contraction in first quarter 2020, followed by a strong bounce-back in second quarter 2020 and a return to a firmer path heading into 2021, similar to projections at the beginning of the year.

Private forecasters reacted to the impact of widening isolation policies globally and heightened COVID-19-related global uncertainty, shifting their outlook along three Ds—the depth, duration and diffusion across countries of the expected economic contraction.

By March 23, a much deeper and longer-lasting recession across a wider range of countries was predicted than had been envisioned just two weeks earlier. Since then, the projections have shifted toward a more severe recession, and a rebound to the path forecasted on Jan. 1 for mid-2021 no longer appears likely.

The worldwide downturn is also much more broad-based across sectors and industries than it was during previous global recessions, when a resilient service sector could help buffer the fall.

Check mark-shaped global recovery envisioned

Chart 3 illustrates the observed path of global output up to fourth quarter 2019 (black solid line), using data from the same national sources captured in DGEI. It also shows the quarterly path as projected from first quarter 2020 until second quarter 2021 (dashed lines), using aggregated forecasts based on Consensus Economics’ daily data.

The figure highlights the firming of global growth predicted on Jan. 1 (light blue dashed line) as well as the implied V-shaped recovery on which private forecasters coalesced by March 9.

By the time British Prime Minister Boris Johnson on March 23 ordered the public in the U.K. to stay home (yellow dashed line), the more optimistic view of a V-shaped recovery was already being abandoned. Increasingly, the expected path of the recovery started to resemble a "check mark" through second quarter 2021.

By April 2 (dark green dashed line), the global economy appeared set for a recession based on two consecutive quarters of negative growth, and the prospects for a near-term recovery appeared dim. A number of plausible scenarios could materialize, shifting the expected global output path (the expected check mark-shaped recovery).

A relatively benign hypothesis would anticipate a U-shaped recovery. The rationale here envisions that COVID-19 may linger until the summer, with restrictions loosening gradually. While fiscal and monetary stimulus props up demand and employment, it takes time to return to full capacity and recover trade relations. Thus, growth is not on a firmer footing until late 2021 or beyond.

A less-benign hypothesis would be that loosening controls prematurely may allow the virus to stage a comeback in the fall, a possibility suggested by researchers at Imperial College London. This may result in a W-shaped recovery as restrictions are reintroduced and uncertainty reignites.

The least-benign scenario is that the bounce-back arises from a temporary leveling of activity, while the path from 2021 onward is more L-shaped—a result of a weakened medium-term outlook. This could reflect factors such as economic strains from a COVID-19-related sovereign debt buildup and fears of a financial crunch and heightened uncertainty as well as protectionist and interventionist economic policies.

Charting impact of monetary and fiscal intervention

Longer-term forecasts suggest that the more-benign scenario for the economic recovery remains the benchmark among private forecasters—albeit tempered by a prolonged downward shift in the expected global output path—given the increasingly robust monetary and fiscal support deployed to deal with the consequences of COVID-19.

The path of recovery will depend on how policymakers, households and firms respond to the impact of the coronavirus spread as efforts continue to curb risks to the global economy and improve long-term growth prospects.

The global economy’s path should be more apparent as new data become available and with the upcoming release of hard indicators, such as those captured in the Database of Global Economic Indicators.

About the Author

Enrique Martínez-García

Martínez-García is a senior research economist and advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.