How sensitive are interest rates to higher federal debt?

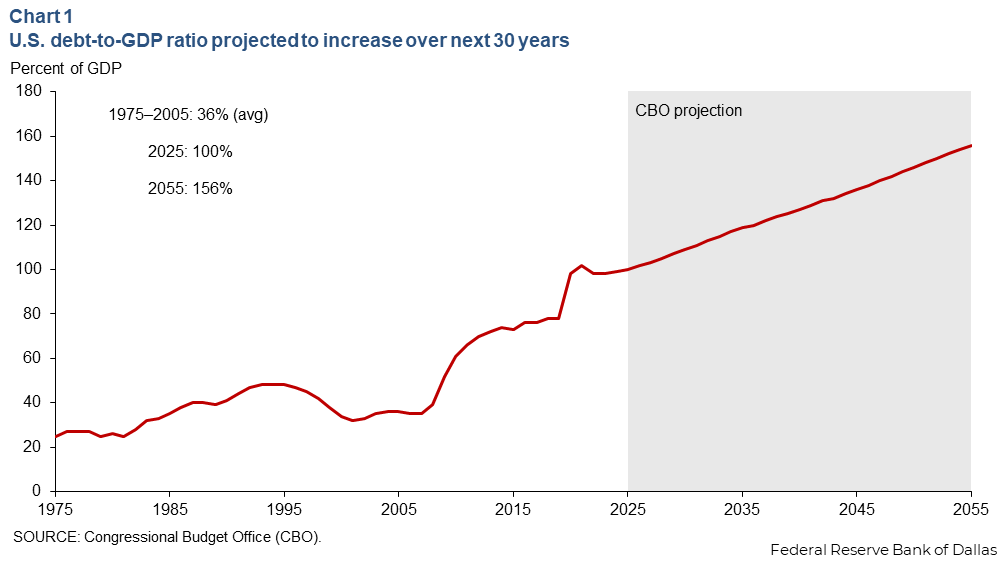

The U.S. faces a historically high federal debt-to-GDP ratio, a measure of debt relative to economic output. While federal debt was relatively stable from 1975 to 2005, averaging 36 percent of GDP, it has since risen to 100 percent of GDP.

Debt is likely to further increase in the future, with the January 2025 projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) showing debt climbing to 156 percent of GDP by 2055 (Chart 1).

There is concern that growing federal debt could push up interest rates, which could negatively affect investment and the broader economy. An important question: How sensitive are interest rates to higher debt?

Our estimates, in a new working paper, show that each percentage point increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio increases long-term interest rates by 3 basis points. (100 basis points equal 1 percentage point.) This suggests, holding all else equal, long-term interest rates could rise more than 1.5 percentage points over the next 30 years if debt increases as projected.

Identifying how interest rates respond to federal debt

Estimating the effect of federal debt on interest rates is empirically challenging. For example, deficits, and therefore debt, often rise during recessions due to automatic stabilizers and discretionary fiscal stimulus, while interest rates tend to fall in response to easing monetary policy. These dynamics can obscure the underlying, long-term relationship between federal debt and interest rates.

An influential research paper published in 2009 proposed using long-term forward interest rates and projections of future debt levels to mitigate these issues. These variables are potentially less sensitive to short-run changes in the economy and, therefore, provide a better signal for what the market expects. A regression model can then quantify how interest rates respond to changes in debt.

The model proposed in the paper posits that nominal interest rates respond to inflation expectations, debt and potentially other variables, such as risk aversion and expectations about future economic growth. Recent research has also argued for including Federal Reserve and foreign official holdings of U.S. debt to help account for some of the demand-side factors that may have also influenced interest rates, particularly in recent decades.

Naturally, the success of this approach relies on having current and past forecasts for debt. The CBO has released five-year-ahead fiscal projections, usually once or twice a year, since 1976. Academics and policymakers widely use these projections.

Less obviously, the success of this approach also requires the nominal interest rate to closely track expected inflation. An important finding of our work is that this assumption is no longer valid once we extend the data through 2025. When this condition is not met, the estimates of the interest rate sensitivity to debt tend to be invalid.

Our solution is to specify that the change in interest rates, rather than the level of interest rates, is related to changes in debt and the other control variables. This approach sidesteps the data issues that affect the original model.

Revisiting the relationship between federal debt, interest rates

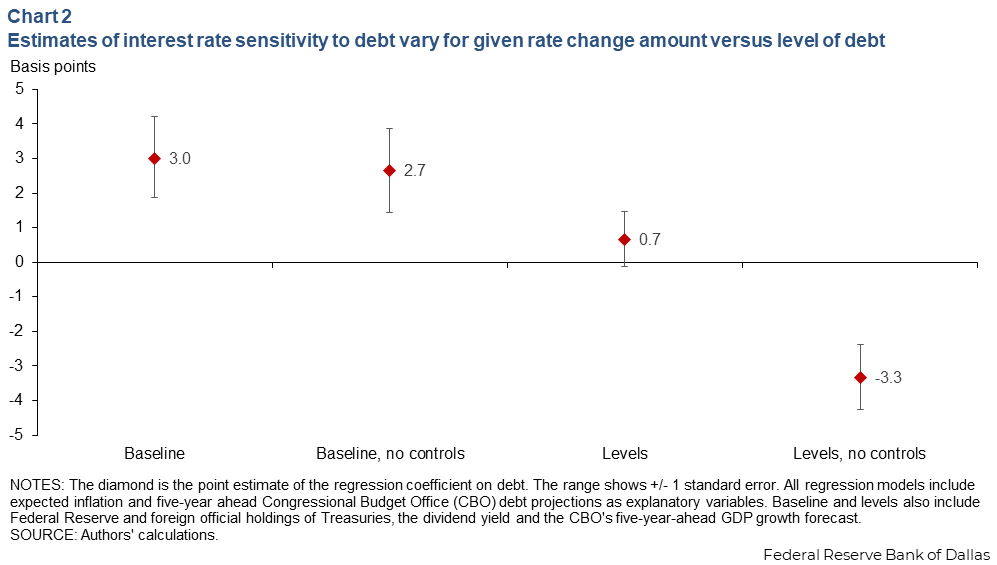

Using our approach, we find that a 1 percentage point increase in the projected debt-to-GDP ratio increases the 5-year-ahead, 5-year Treasury rate by about 3 basis points (Chart 2, baseline). We obtain a similar estimate even when no extra control variables are included in the model (Chart 2, baseline no controls). The response is also precisely estimated, as indicated by the narrow range in Chart 2.

Additional analysis shows that these results are robust to different sample periods, using longer-term forward interest rates (for example, 5-year-ahead, 10-year Treasury rate), and even using alternative debt projections produced by the Office of Management and Budget.

Both of the baseline estimates are significantly larger than what one finds with the original model, where the variables are specified in levels. In that case, the increase in the 5-year-ahead, 5-year Treasury rate is less than 1 basis point when controls are included in the model and negative when the controls are excluded.

Since 1996, the CBO has also released 10-year-ahead projections. In theory, these projections should be even less sensitive to short-run economic conditions. Using these projections, we find a similar interest rate response to debt compared with what we obtained with the 5-year-ahead projections, but the estimate is far more precisely estimated.

Changes in federal deficits also affect interest rates

Prior research has also considered how interest rates respond to federal deficits. Once again, we use 5-year-ahead CBO projections to identify this response. Using our approach, we find that a 1 percentage point increase in the projected deficit-to-GDP ratio increases the 5-year-ahead, 5-year Treasury rate by 17 basis points. The deficit includes (net) interest spending on the debt, potentially raising some concerns about the estimation. However, when we use the projected primary deficit, which excludes interest spending, we obtain a similar, 14-basis point increase in the 5-year-ahead, 5-year Treasury rate.

Since deficits are persistent, a 1 percent increase will lead to a more than 1 percent increase in debt over time. The estimated coefficient on the primary deficit-to-GDP ratio is about four times larger than the coefficient on debt-to-GDP ratio. This result is consistent with the persistence of past primary deficits in our sample period.

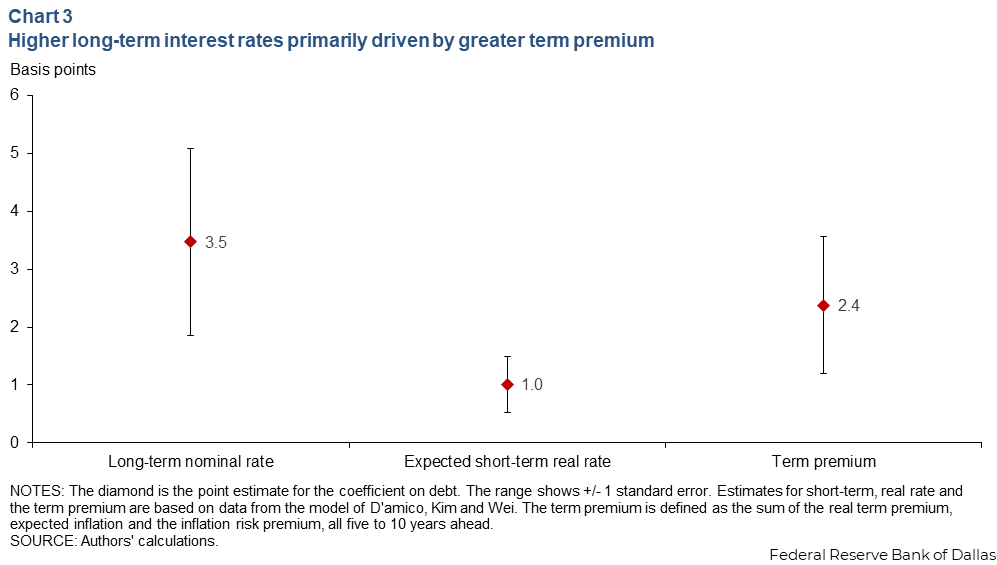

Term premium adjusts to federal debt

Long-term interest rates reflect not only expectations about short-term real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates but also the term premium, the additional compensation investors receive for holding the longer-term debt. The shift in nominal interest rates that we document could be due to changes in either of these components. Understanding this breakdown is important. If the effect is concentrated on expected short-term real interest rates, it would affect the stance of monetary policy (Chart 3).

We find that about three-quarters of the debt-induced rise in long-term interest rates is attributable to an increase in the term premium rather than expected short-term real interest rates. This finding aligns with recent high-frequency identification studies, which show that bond markets quickly and disproportionately adjust term premia in response to fiscal news.

Potentially large effect on long-term interest rates

Rising debt levels are likely to push up interest rates on U.S. government debt. We find that each percentage point increase in the debt-GDP ratio increases long-term interest rates by about 3 basis points. Our estimate is substantially larger than the 0.7 basis point effect estimated using the traditional approach—which we argue is affected by statistical issues—and also larger than the 2-basis-point effect the CBO uses for its analysis and projections.

All else equal, our estimate suggests long-term interest rates could rise by more than 1.5 percentage points over the next 30 years if debt rises to 156 percent of GDP, as the CBO projects.

About the authors