Policymakers’ response to COVID-19 can draw on Great Recession lessons

The spread of COVID-19 and the global response to it have severely disrupted economic activity and heightened uncertainty. Asset price volatility and fears of financial turmoil have also emerged, further clouding the outlook.

Central banks’ experience before and during the 2007–09 Great Recession suggests that they have ample tools to support the economy in the face of such risks.

Financially healthy businesses are essential to keeping the economy running and avoiding a protracted recession. We focus here on what monetary policy can do to aid the economy should worsening financial conditions cause companies to invest less, scale back operations or go bankrupt in large numbers.

How Monetary Policy Works

The interest rates offered on government debt of various maturities are represented by the yield curve. Banks use the yield curve as the basis for administering loans, adjusting rates charged based on observable characteristics of a borrower’s credit risk. Hence, the transmission of monetary policy partly depends on exercising influence on long-term interest rates, a key part of household and business financial planning.

Long-term interest rates contain information on the cumulative effects of short-term maturities as well as a premium to compensate bondholders for the added risk on longer-term obligations. The Fed can provide monetary accommodation if it credibly shifts perceptions about the future path of the federal funds rate, thus lowering long-term yields.

The Fed can also affect yields by reducing the uncertainty surrounding future policy actions, helping narrow the premium on longer-term rates. Additionally, it can utilize its toolkit to mitigate the impact of financial risks through various financial-market backstops while helping maintain market liquidity when financial conditions are poor.

Central Bank Policy More Effective When Predictable

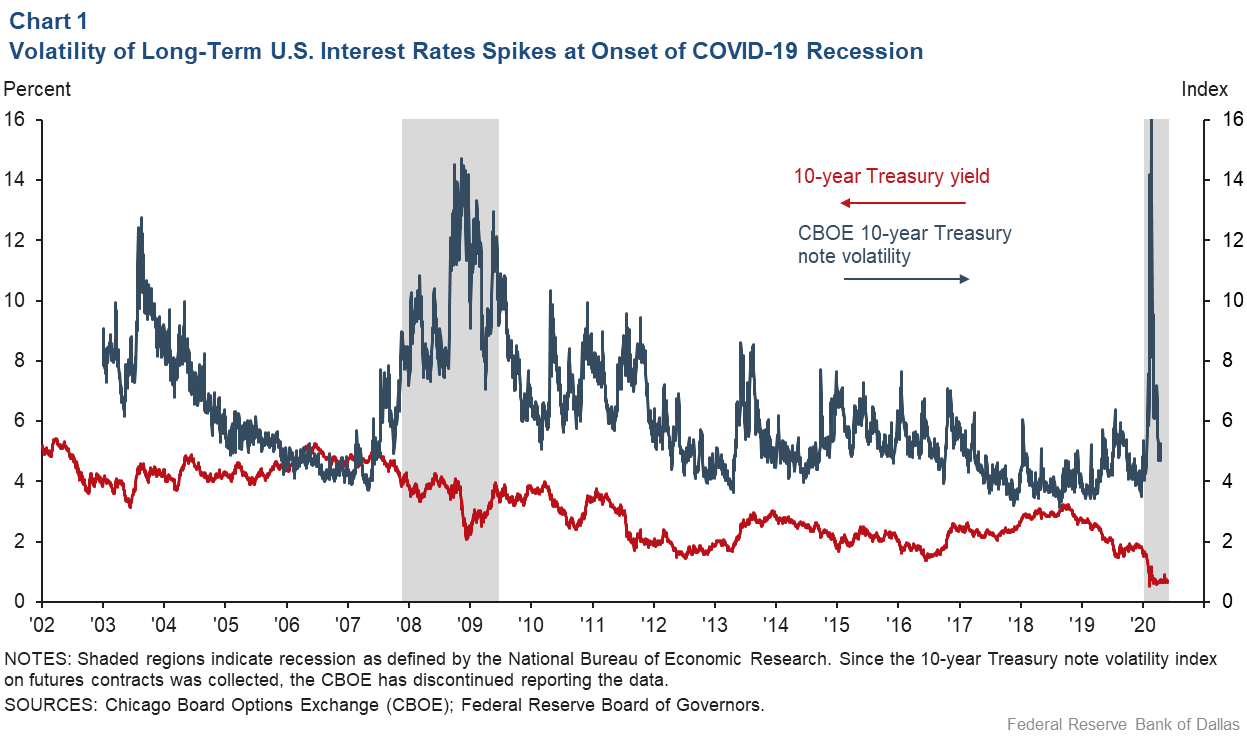

When the policy path is more uncertain, unhedged interest rate volatility may suddenly spike (Chart 1). If sustained, this makes forecasting and financial planning more uncertain and can lead businesses to abandon or postpone investment projects. Companies that can’t adjust costs or revenues quickly are also at an increased risk of default during high-volatility periods.

All told, minimizing monetary policy uncertainty could reduce aggregate output volatility and interest rate volatility in the U.S. by as much as one-third. By effectively communicating the monetary policy path, the Fed can help make funding more predictable and ease borrowing costs. That improves financial conditions for businesses beyond what setting a more accommodative policy could do alone.

Labor Intensity, Debt, Business Uncertainty Heighten Financial Risk

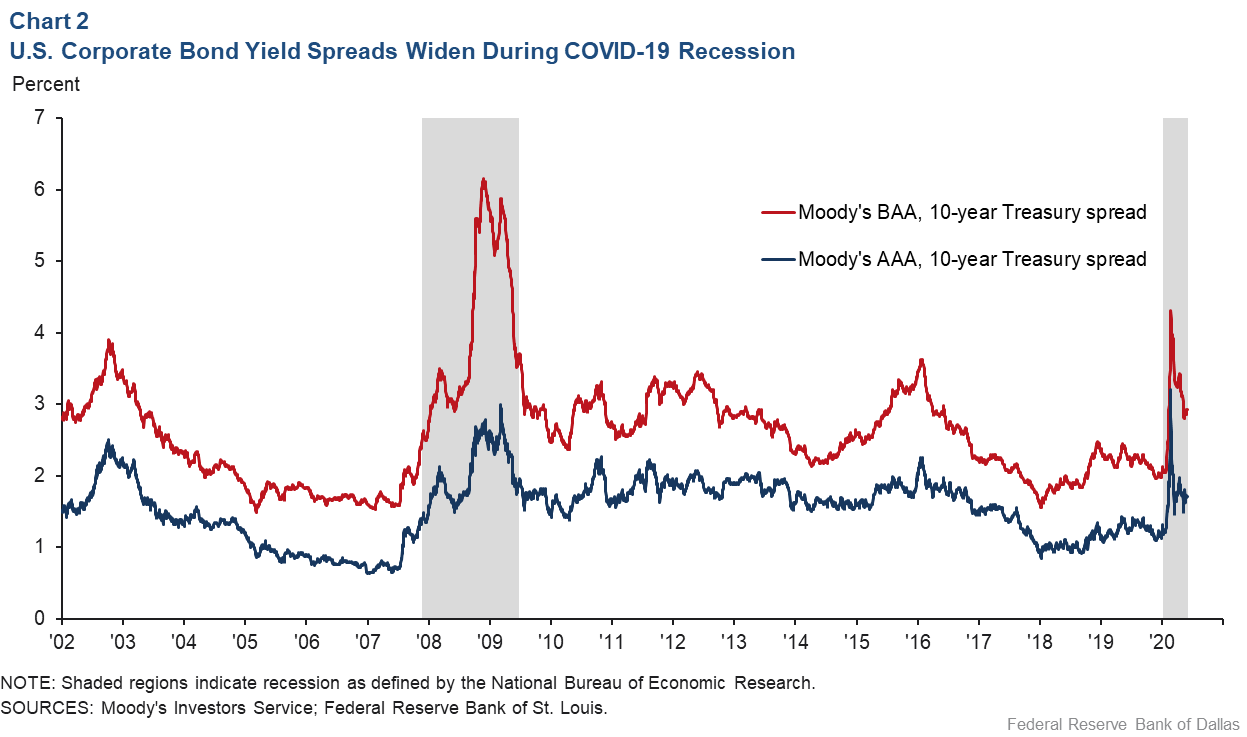

Businesses’ borrowing costs generally exceed Treasury yields of a comparable maturity. The spread between them partly reflects the perceived risk of business default (Chart 2). The spread prices the costs of monitoring borrowers and of litigation in case of bankruptcy, which tend to vary with observable borrower characteristics reflecting credit worthiness.

One such observable borrower characteristic is labor intensity. In the past, more labor-intensive industries have typically had an easier time navigating a downturn than capital-intensive ones, which must continue servicing loans on their now-underutilized fixed capital.

The impact of the government response to COVID-19, however, has been particularly disruptive for many labor-intensive industries, such as restaurants and hotels, which in some cases have closed in response to edicts from authorities or to sharply curtailed consumer demand.

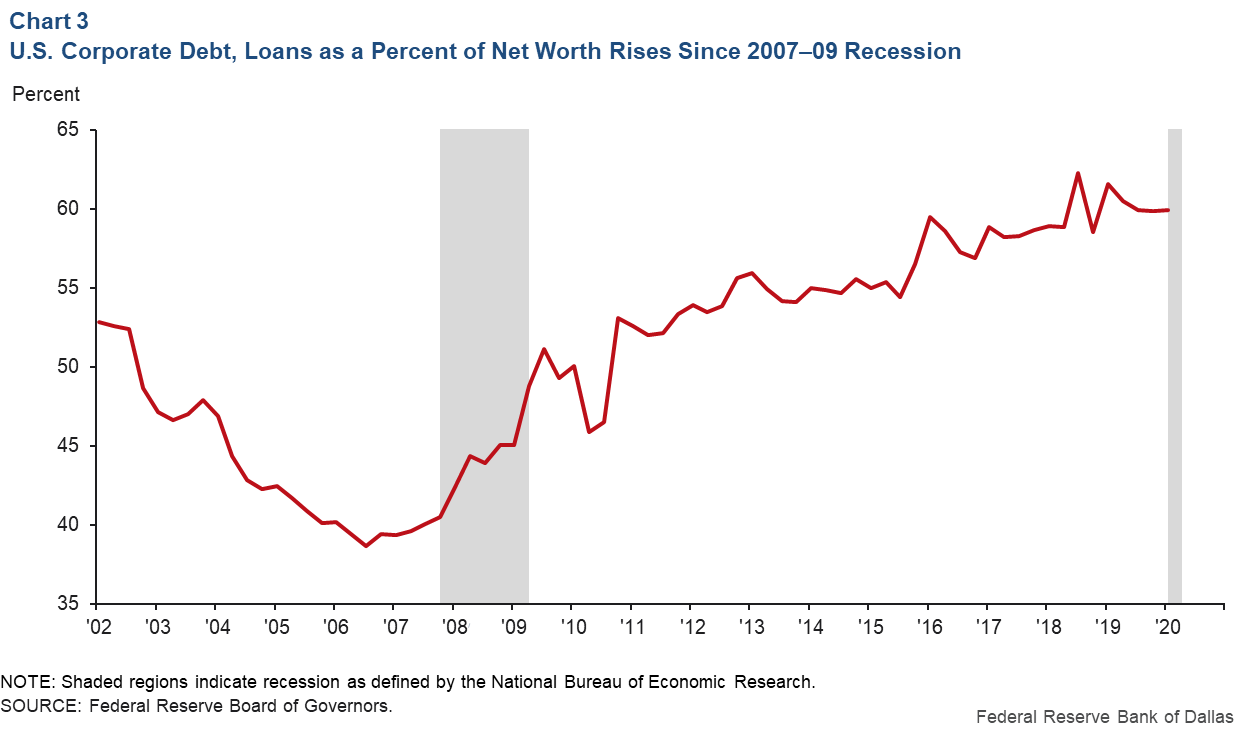

Another important borrower characteristic is financial leverage, shown as a percentage of debt and loans over net worth. U.S. corporations have become more indebted since the 2007–09 financial crisis, partly due to companies taking advantage of low interest rates (Chart 3). By leveraging up, firms increased return on shareholder equity, helping propel the stock market. In the process, the added debt left them at greater risk of default and of higher credit risk spreads during a future financial crisis, such as the COVID-19 disruption.

Firms in the same industry and with comparable financial leverage still differ in product sales, prices and costs because of hard-to-measure human and managerial capital, organizational flexibility and productivity. A major concern during the COVID-19 crisis is the possibility of a sharp increase in business-specific (or micro) uncertainty widening the disparity of outcomes, severely increasing the risk of default and worsening credit conditions broadly.

Monetary Policy Most Impactful When Financial Conditions Poor

Business-specific “micro-uncertainty” shocks resemble aggregate demand shocks—aggregate output and inflation fall when business uncertainty spikes. When credit conditions are poor, as evidenced by elevated credit risk spreads, additional micro-uncertainty shocks are further amplified. Negative effects become enhanced as credit spreads keep rising, feeding a financial crunch.

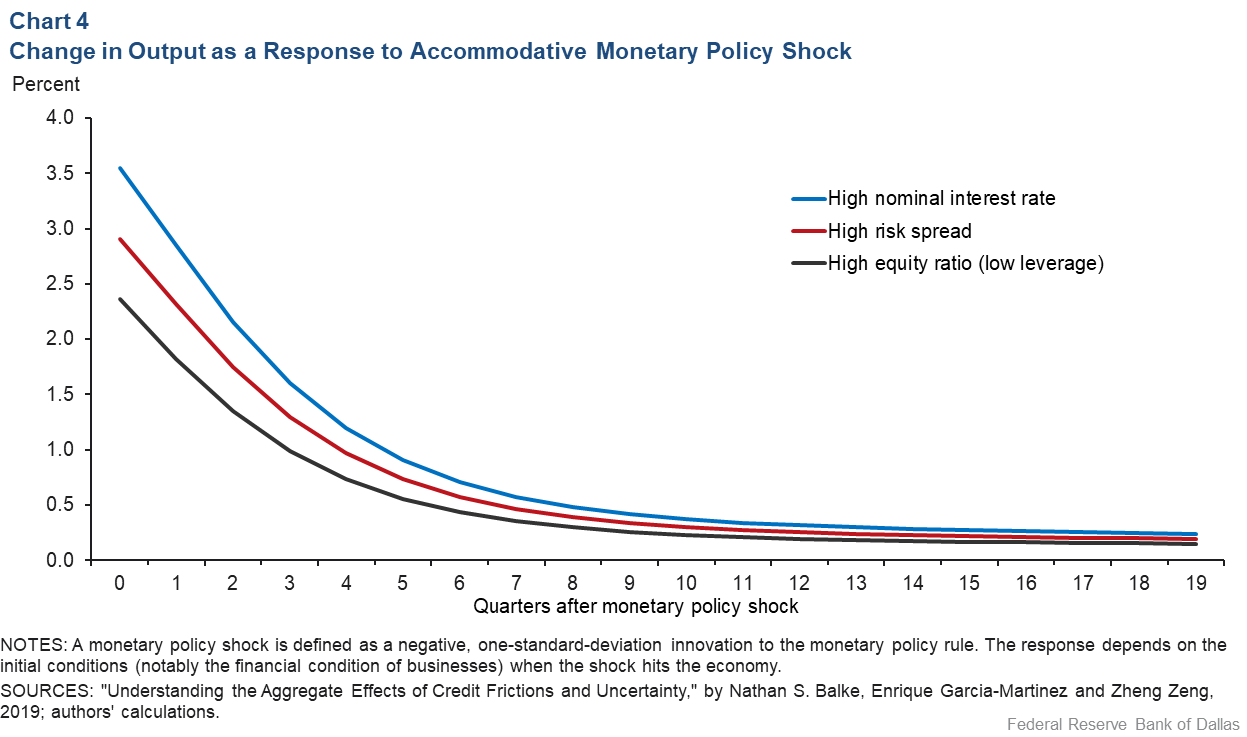

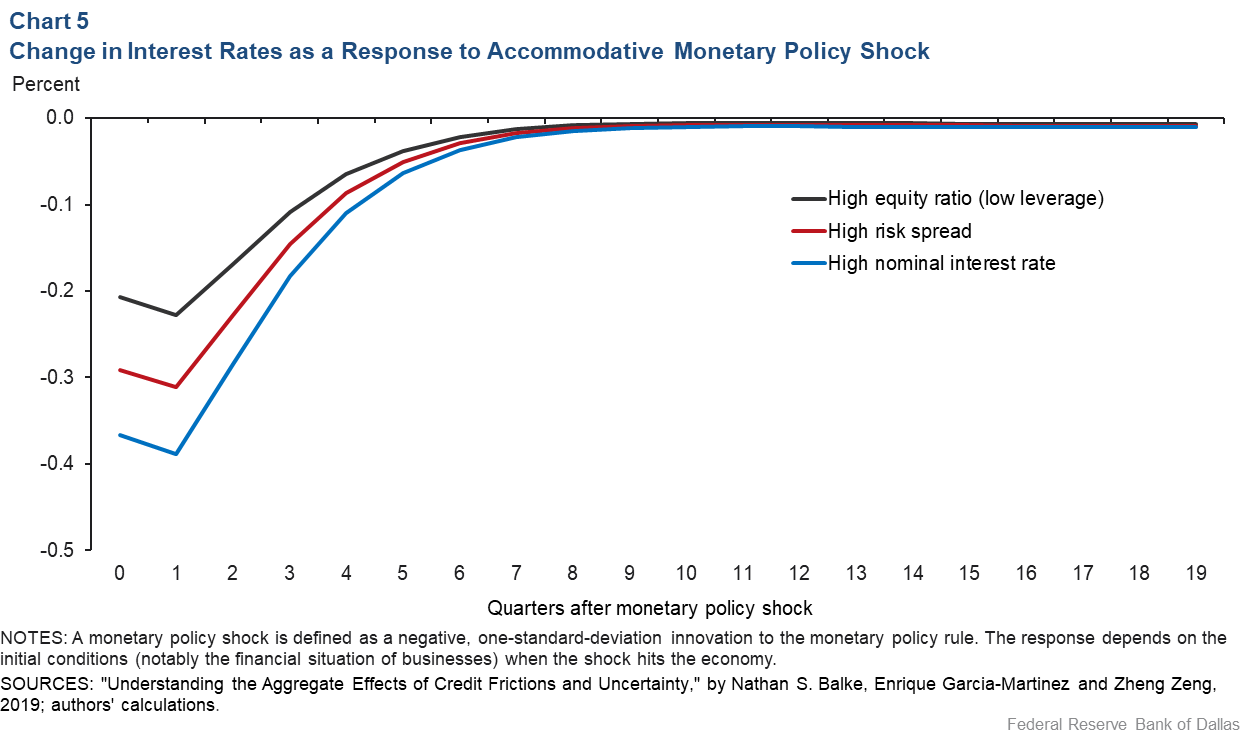

The monetary response to an emerging financial crunch is stronger when the credit conditions of borrowers are already poor or when policy rates are high. The intuition is that monetary policy accommodation works by lowering yields, but also—to a certain extent—by compressing the credit risk spreads. Lowering rates along the yield curve eases borrowing costs and the erosion of profit margins, keeping more firms viable, lowering default risk and narrowing credit spreads.

We illustrate the effects of monetary policy accommodation with impulse-response plots in Charts 4 and 5, which visualize the path of output and the policy rate, respectively, after an accommodative policy shock to the U.S economy. These estimated responses show that the marginal benefits of monetary accommodation decrease as firms deleverage and policy rates fall.

From this evidence, it follows that the low-interest-rate environment that preceded the COVID-19 crisis limits the efficacy of monetary policy to ease credit conditions now. That is, when the yield curve is already low, businesses are less sensitive to central bank stimulus.

However, this evidence also favors acting quickly and aggressively when credit risk spreads spike. Even unconditionally, cutting rates by about 50 basis points (a half-percentage point) is estimated to provide more than 2.15 times the output boost on impact than is achievable with a cut of just half that size.

Monetary Policy Response to COVID-19 Recession

After 12 years of uninterrupted growth—the longest U.S. expansion in the post-World War II period—the economy is in the midst of a once-in-a-century-magnitude recession. Some aspects of this global downturn have been unique: the unpredictability surrounding COVID-19, tumbling oil prices and uncertainty about fiscal responses. Nonetheless, the Federal Reserve can still perform a principled and effective response to improve financial conditions and to broadly support the economy, even at the zero lower bound.

Since the 2007–09 financial crisis, the Fed has found itself grappling to achieve its statutory mandate in a persistently low-interest-rate environment. It has expanded its policy space with large-scale purchases of financial assets, updated communication practices to credibly signal its economic outlook and policy expectations, and added an explicit inflation commitment. Through it all, the Fed has gained a greater understanding of its broad toolkit.

Furthermore, the Fed can also draw from its 2007–09 recession experience in formulating a nuanced response to the COVID-19 crisis that supports the economy while contributing to the mitigation of financial risks and their negative economic outcomes.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.