Why house prices surged as the COVID-19 pandemic took hold

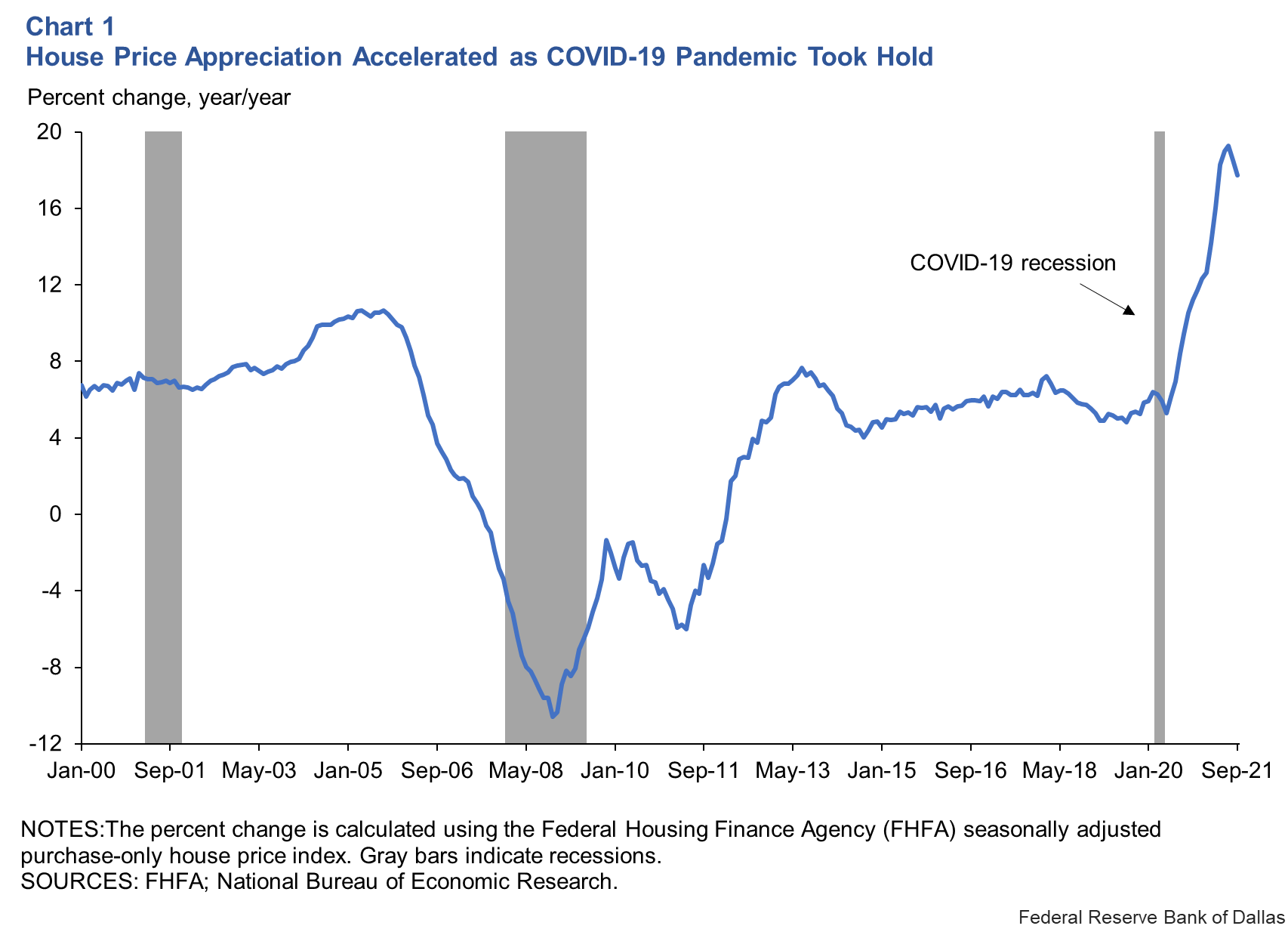

In the wake of the short but steep COVID-19 recession, house prices have risen at record levels in recent months, hitting the peak increase of 19.3 percent in July 2021 (Chart 1). These double-digit increases represent a stark departure from what occurred before the pandemic—from early 2013 to early 2020—when house prices rose at a moderate annual rate of about 5 percent and exceeded the rate of increase in rents.

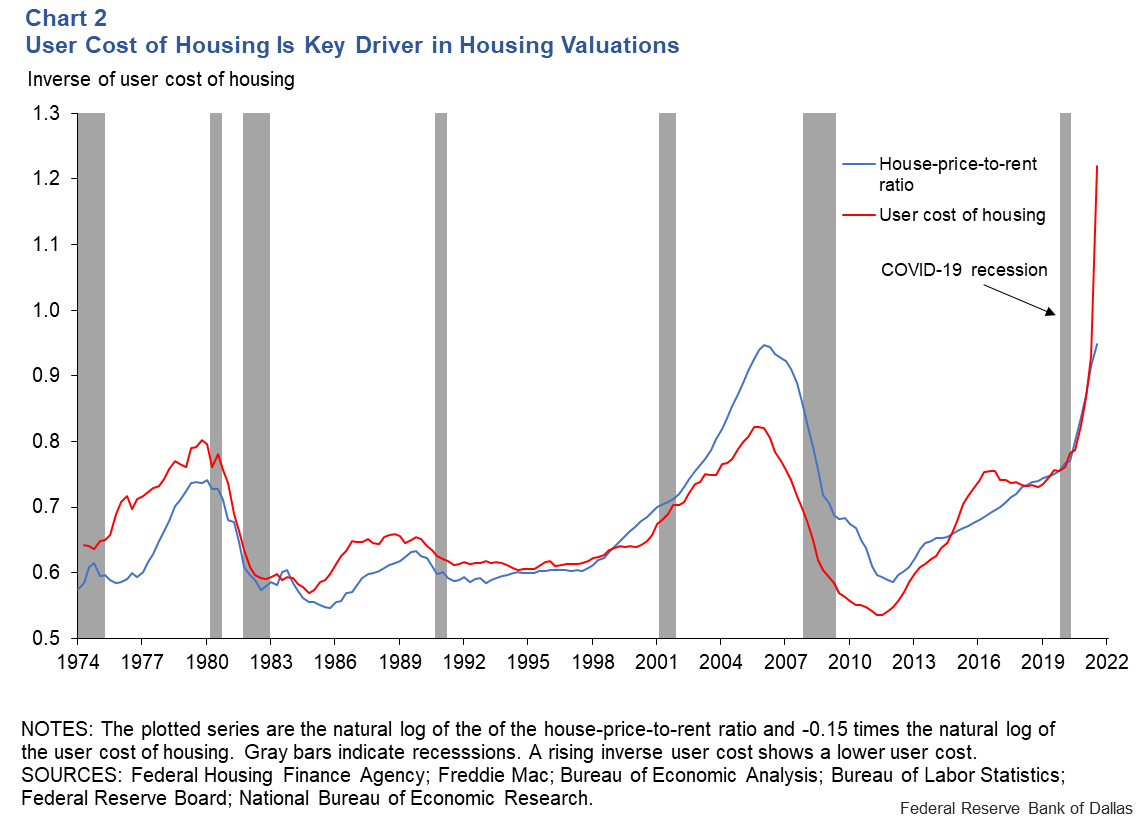

The resulting rising house-price-to-rent ratio, a barometer of relative housing costs, reflected a moderate prepandemic increase in house valuations.

This rise was the product of a limited increase in the supply of houses for sale, a growing share of the population ages 25–40 that typically buys homes, a healthy economy and some easing in lending standards for prime borrowers.

The pandemic and the demand for housing

The acceleration in house prices immediately following the COVID-19 recession was very different from the steep decline triggered by the subprime bust in the February 2007 to June 2009 Great Recession. The stark dissimilarity owes to the recent and unusual combination of positive housing demand shocks, negative housing-supply shocks and swift and decisive polices to support the economy. Unlike the lead-up to the Great Recession, homeowners were not overleveraged, and lending standards were not too loose.

During the pandemic, large transfer payments that included stimulus checks and extended/expanded unemployment benefits boosted household incomes. As a result, household incomes and housing demand did not collapse when unemployment spiked to a seasonally adjusted 14.8 percent in April 2020 (from 4.4 percent a month earlier).

In addition, very low mortgage interest rates, reflecting market forces and very accommodative monetary policy, raised the demand for housing. The Federal Reserve cut its policy rate to the effective lower bound (0 percent), purchased large quantities of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (quantitative easing or QE), and provided forward guidance that the fed funds rate was likely to remain at the effective lower bound for an extended period.

The pandemic also boosted the demand for housing by increasing the need to work from home and for more socially distanced housing away from dense urban areas, especially in major cities. The former is reflected in a rise in relative prices of larger suburban homes and the latter in a rise of single-family housing relative to multifamily construction.

Limited supply of new homes

These factors helped push up house prices. In normal times, new construction gradually increases the supply of housing, which limits upward house-price pressure. However, the recent supply response has been muted relative to the rise in prices, and the price response has been magnified by pandemic-related supply constraints. Those constraints include disruptions to supply chains for building supplies and restrictions on work practices.

Additionally, federal and other moratoriums on homeowner evictions and extensive modifications of mortgages by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and other lenders prevented a surge in fire sales of repossessed homes that would have otherwise depressed house prices.

House-price expectations and momentum

The tendency of consumers to base expectations of future house-price appreciation on the recent pace of increase has also boosted the house-price run-up. As people see faster price appreciation, they raise their expectations of future appreciation and their demand for housing. They reason that house prices are rising rapidly, so it is better to get on the housing ladder rather than wait for possibly lower prices in a few years’ time. This amplifies the initial impacts of lower mortgage rates and the higher COVID-19-related demand for single-family housing.

This momentum shows up in the so-called “user cost” of housing, the difference between the tax-adjusted mortgage rate minus the expected rate of house-price appreciation, a widely used measure of the cost of housing, albeit one that ignores affordability and mortgage lending standards.

Chart 2 plots the logarithms (a way of looking at a rate of change) of the house-price-to-rent ratio and the inverted user cost of housing. The two appear to track one another. When the user cost is low or negative, the house-price-to-rent ratio is generally high.

The user cost of housing is currently very low because mortgage interest rates are low and expected house-price appreciation is very high.

Momentum effects fade, fundamentals kick in

Eventually, the house-price-to-rent ratio will stop rising and may even recede. As prices rise relative to fundamentals such as income, they lower housing affordability. Fewer households will qualify for mortgages to buy homes, and upward pressure on demand will wane. In addition, new construction will add to the supply. As valuation pressures start to dominate, expected house-price appreciation rates will slow, raising the user cost of housing, reducing demand and reversing the upside momentum we see now.

These downward pressures could be reinforced if some of the increased demand for additional space fades as the pandemic ebbs. Because it is unclear how permanent this demand shift is, there is uncertainty about how much—if at all—the house-price-to-rent ratio will retrace its recent run-up.

The house-price-to-rent ratio could also slowly adjust downward if house prices stagnate while rents continue rising. Hence, both the timing and degree of any eventual tempering in house prices are uncertain. Nevertheless, in the very near term, the low user cost of housing suggests that house prices seem poised to rise further, barring some unforeseen negative development.

Crucial role of policy response to COVID-19

Due to several factors, house prices have behaved far differently in the wake of the COVID-19 downturn than following the previous recession. Relative to the Great Recession, the recent financial conditions of households and the financial system were much stronger, while countercyclical macroeconomic policies aimed at tempering the effects of the pandemic downturn were conducted faster, more strongly and more broadly.

These policies prevented recessionary pressures from lowering house prices. Instead, the combination of lower interest rates, support for household incomes, a pandemic-related rise in demand for home offices and single-family homes, supply constraints, widespread mortgage forbearance and moratoriums on evictions pushed up house prices. The gain received support from revived expectations of future price appreciation.