A Ban on U.S. Crude Oil Exports Would Not Lower Gasoline Prices at the Pump

High gasoline prices have stimulated interest in what the Biden administration can do to lower the price at the pump. We argue that there is little policymakers can do to address this concern. Calls for a U.S. crude oil export ban, in particular, appear counterproductive.

High U.S. fuel prices in October 2021 prompted the Biden administration to consider a variety of policy measures to reduce the prices at the pump after OPEC+ (consisting of OPEC and its oil-producing allies such as Russia) declined to raise its oil production further. Most prominent among these measures have been calls for a release of oil from the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) and for a U.S. crude oil export ban.

In late November 2021, the administration announced that the Department of Energy would release 50 million barrels of medium-grade crude from the SPR in an effort to lower the price of gasoline, hoping that OPEC+ would not offset this release by cutting its production targets.

How the SPR Release Works

The 2021 SPR release accelerates to early 2022 an 18-million-barrel sale of crude oil authorized by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 for the fiscal years 2022–25. The release also includes a 32-million-barrel SPR exchange that allows refiners to borrow crude oil starting in December 2021. This oil must be returned with “interest”—in the form of additional barrels of oil—over the following three years.

It is unclear what the demand for this oil will be, given that SPR exchanges are designed to deal with temporary supply shortfalls rather than persistent gasoline price increases driven by higher demand. Indeed, there are concerns that oil prices may surge, starting in 2023, when rising demand after the COVID-19 pandemic confronts inelastic supplies following years of underinvestment in oil production.

Hence, evidence for the success of previous SPR releases intended to offset temporary oil supply shortfalls (as discussed in “Does Drawing Down the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve Help Stabilize Oil Prices?” by Lutz Kilian and Xiaoqing Zhou) provides little insight about the effects of the latest SPR release, which was prompted by persistent supply shortfalls.

Another important concern is how much appetite there will be among U.S. refiners for additional sour medium crude of the type made available through the SPR, given that many refineries typically process other types of oil.

While the effectiveness of the recent SPR release on the price of West Texas Intermediate crude oil will continue to be debated, the emergence of the COVID-19 Omicron variant after the SPR release in November 2021 led many forecasters to lower their global demand outlooks for 2022, resulting in a substantial decline in the oil price.

As a result, Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm, who had broached the subject of an oil export ban in October 2021—describing it as another possible tool—recently signaled that such a measure was off the table. Although the idea of a U.S. crude oil export ban has been shelved for now, it is useful to reflect on its economic merits because this idea may reemerge if pump prices rise again in the coming months.

Would an Oil Export Ban Be More Effective than an SPR release?

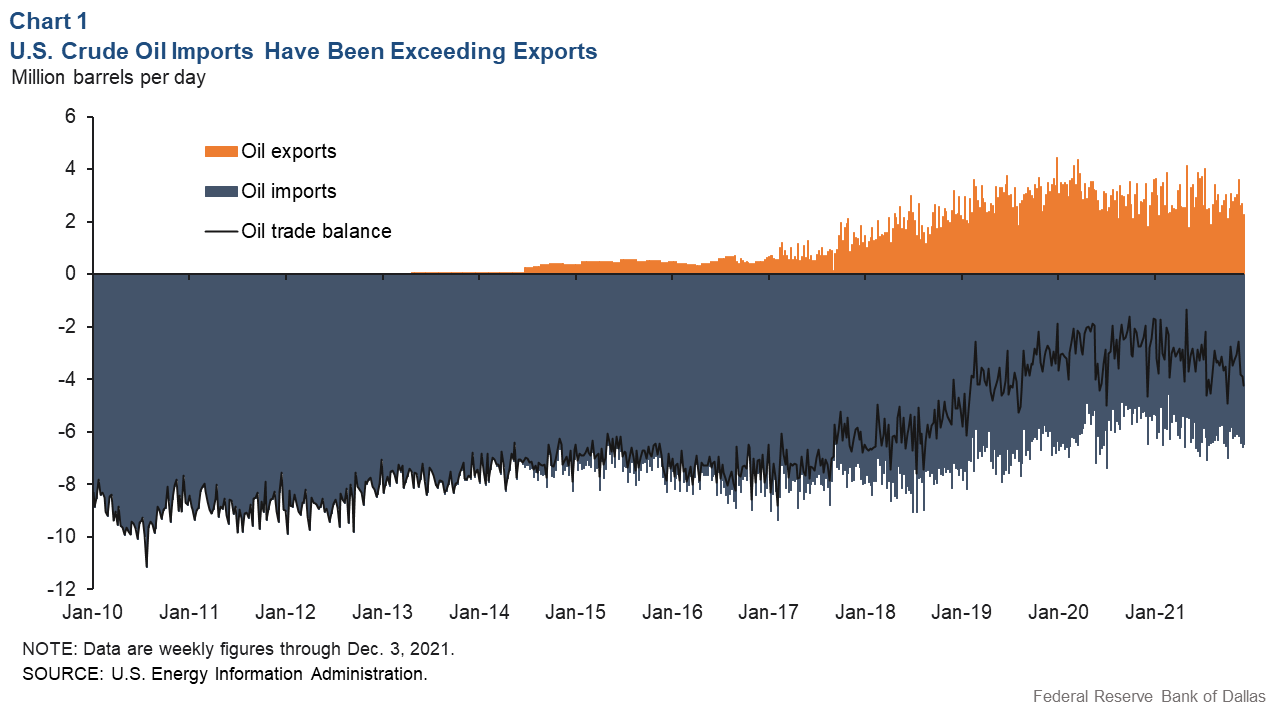

At the end of November 2021, the United States exported an average 3 million barrels per day of mainly light sweet crude oil that U.S. refiners lack the capacity to process. Meanwhile, refiners imported more than 6 million barrels of mostly heavier crudes from Canada and other foreign suppliers that are unavailable domestically (Chart 1). These heavier crudes play an important role in the production of diesel fuel and jet fuel.

Proponents of a U.S. crude oil export ban argue that prohibiting crude oil exports would increase the supply of crude in the United States, allowing refiners to increase their production of gasoline and diesel and lowering the price of these fuels. The implicit premise is that there is enough spare capacity for this light sweet crude oil to be refined in the United States.

One important point this proposal overlooks is that the prices of gasoline and diesel in the United States are determined by their prices in global markets since the U.S. trades diesel and gasoline. Because a cessation of U.S. crude oil exports would lower the supply of oil in global markets and raise its price, one would expect global fuel prices, if anything, to increase as a result. Refiners can always sell these fuels abroad at their global price, so it makes no sense for them to sell for less in the domestic market.

In other words, the prices of gasoline and diesel fuel in the U.S. would not be expected to decline and might actually increase, rendering the crude oil export ban not only ineffective, but also counterproductive. Thus, there is no reason to expect that U.S. consumers would benefit from such a ban.

Banning crude exports, however, would benefit refiners of light sweet crude in the short run because they can buy crude oil that otherwise would have been exported at a discount, while selling fuels at high global prices. This is not merely conjecture. “The Impact of the Shale Oil Revolution on U.S. Oil and Gasoline Prices,” by Lutz Kilian, provides evidence supporting this point from before 2015, when exports of domestically produced crude were largely banned for national security reasons.

The short-run bonanza for U.S. refiners specialized in refining light sweet crude, however, would not last. As the price of domestically produced crude oil declines and storage fills, it would not be long before some domestic oil producers become unprofitable and cease operations.

Broader Implications for the Economy

Eliminating U.S. crude oil exports would also raise the overall U.S. trade deficit and would make the U.S. more dependent on foreign oil in the long run. As more oil is imported, more consumer dollars spent on fuel end up abroad, increasing the exposure of the U.S. economy to rising oil prices—an exposure that has been unusually low in recent years by historical standards.

Although one could argue that renewable energy will reduce the reliance on oil over time, given current technologies, most projections envision continued demand for fossil fuels near current levels for years to come, with renewables accounting for the increased overall energy demand as the economy grows.