Solar lights up outlook for renewable energy in Texas

Texas, long known for oil and gas production, is experiencing a boom in utility-scale solar power.

Among renewable energy producers, Texas has been a powerhouse in wind power for more than a decade and has more installed capacity than any other state in the country. However, installed solar capacity has lagged wind for many years.

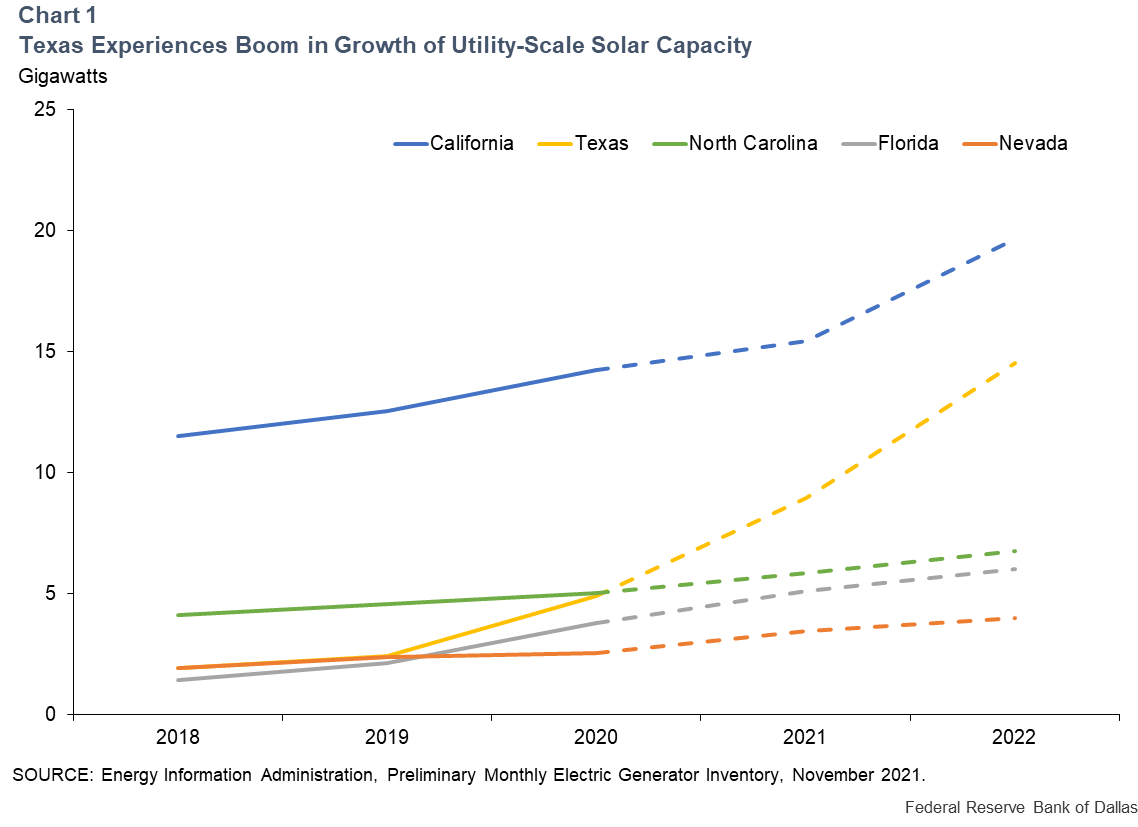

Recently, though, improving economics and government tax incentives have spurred investment in utility-scale solar facilities in Texas. Capacity in the state is expected to triple by the end of 2022 from 2020 levels, although ongoing supply-chain issues remain a risk to that outlook. This expansion would put Texas behind only California in terms of utility-scale solar power (Chart 1).

Developers look to solar amid declining costs

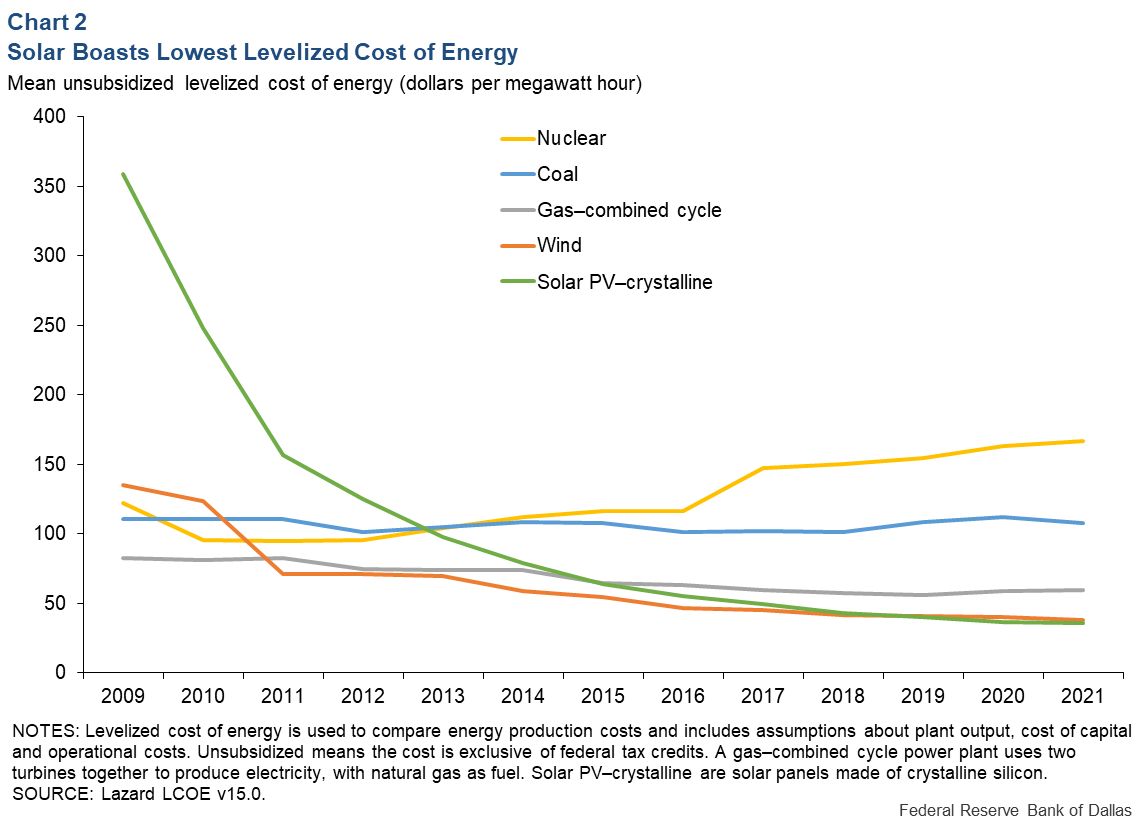

Dramatically declining cost to produce solar power over the past decade has boosted the attractiveness of investing in new solar capacity. This is reflected in estimates of the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for solar power.

The LCOE is one commonly used measure of the cost of producing electricity using a particular type of energy generation. The calculation requires making assumptions about factors such as how much electricity will be produced at a facility, its cost, the cost of capital, the tax rate, the lifespan of the system, and operations and maintenance expenditures.

The LCOE for solar has declined by more than 90 percent since 2009, according to financial advisory firm Lazard (Chart 2). Estimates from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and other similar sources show a comparable trend.

LCOE estimates are also sometimes used to evaluate the costs of producing electricity with various fuels. They suggest that solar power is, on average, cost competitive relative to other forms of generating capacity, such as coal, nuclear and natural gas.

However, a low LCOE does not necessarily guarantee that solar is always the most profitable option for an investor or utility looking at new generating capacity. Costs can vary across individual projects—solar or otherwise—and, importantly, the LCOE only measures the cost side of the equation.

A utility-scale solar project produces power only during the daytime and only when it is sunny, which is different from other capacity, such as a dispatchable natural gas plant or a nuclear plant that provides power day and night. Each option faces a potentially different revenue stream because of varying electricity prices at different times of the day or year, among other factors, affecting ultimate profitability.

Federal incentives remain supportive

State and federal incentives often help spur investment in renewable energy. While Texas has a renewable portfolio standard that sets minimum targets for electricity generation from wind and solar, those targets were met many years ago. Thus, federal incentives are a more important determinant in Texas.

A key incentive for solar projects is the federal government’s Investment Tax Credit. It provides a direct credit that covers a portion of the investment costs for a solar project. In its current form, this credit covers 26 percent of qualified costs for projects that begin construction by year-end 2022 and 22 percent for projects beginning construction by year-end 2023.

These tax credits help lower the cost of new projects, increasing their cost competitiveness relative to other power-generation options beyond what the unsubsidized LCOE suggests. For example, Lazard estimates that the subsidized LCOE for solar in 2021 is $30 per megawatt hour, versus $36 per megawatt hour if unsubsidized.

Some projects install batteries to bolster economics

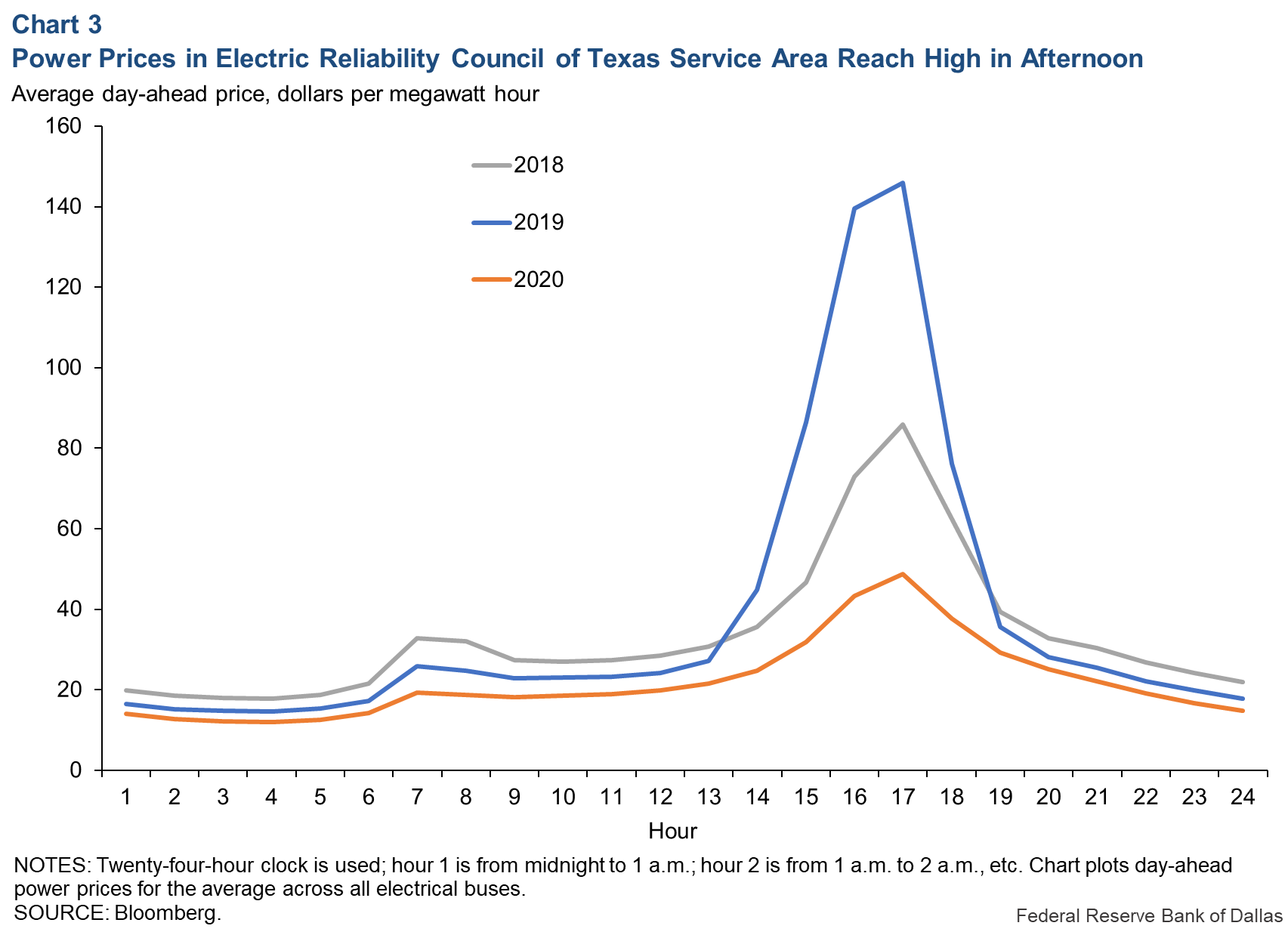

Power prices in the region served through the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) are usually higher during the day than the night, with the price of power typically peaking in late afternoon as people return home from work.

For example, the peak price during 2020, averaged across all days, occurred from 4 p.m. to 5 p.m.—the hour when the greatest power demand generally occurs during summer months—and was 305 percent higher, on average, than the price from 3 a.m. to 4 a.m.—the hour when power demand is typically the lowest (Chart 3).

This price pattern favors solar, since solar generates power during the day when the sun is shining. However, there remains room for improvement. Texas solar-power production generally peaks earlier in the afternoon, before prices reach their highs. Thus, it can sometimes be profitable to store some of the solar power generated, selling it when prices peak in the evening. This is particularly true during peak early-evening summer demand.

Shifting solar power this way requires some storage method that is practical and economic. Some developers have considered batteries as one option. Batteries have not been widely used to store electricity because they remain expensive, despite dramatically declining costs over the past decade. In Texas, batteries accounted for only 0.8 gigawatts (GW) of capacity as of October 2021, just 0.6 percent of total electricity generation capacity in the state. (Depending on the season, a gigawatt can power 300,000 or more homes for a handful of hours.)

Still, recent advances in battery technology, declining costs and government incentives are increasing the attractiveness of battery storage. Among the state’s private power providers, there are plans for 2.2 GW of new battery capacity in Texas through year-end 2022.

A total of 0.6 GW, or 26 percent of the new capacity, is being co-located with new utility-scale solar projects. Pairing solar and batteries together provides two advantages for developers. First, it gives them the opportunity to arbitrage prices across time by selling stored power when prices are highest. Second, it lets them take advantage of the federal investment tax credit that allows investors to cover some battery system costs as long as the project is paired with solar.

Supply-chain issues cloud outlook for planned solar

Recent supply-chain issues have created significant risks to the near-term outlook that could affect how much solar capacity is installed in Texas and elsewhere.

A dramatic increase in the price of polysilicon—a key input to solar panels—as well as higher shipping costs is one risk factor. Polysilicon prices increased about 200 percent at year-end 2021 from year-end 2020 levels, while module (also known as panel) prices rose 22–23 percent, according to Bloomberg data. Existing contracts for purchasing panels will limit the impact of higher prices for some, but new contracts will likely be at higher prices.

Trade issues with China, which dominates the production of solar panels, also creates risks. The U.S. government has moved to prevent the importation of solar panels connected with the potential use of forced labor. As a result, solar panel availability has tightened.

The extent to which these issues will affect capacity expansion in Texas is unclear, but they pose clear downside risks to the outlook in 2022.