High fuel prices in the U.S. may crimp oil demand soon

Oil prices have surged, with benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude jumping from an average $71 per barrel in December 2021 to $109 in May 2022. U.S. inventories of gasoline and diesel are running low and refining capacity is strained, while export demand remains strong.

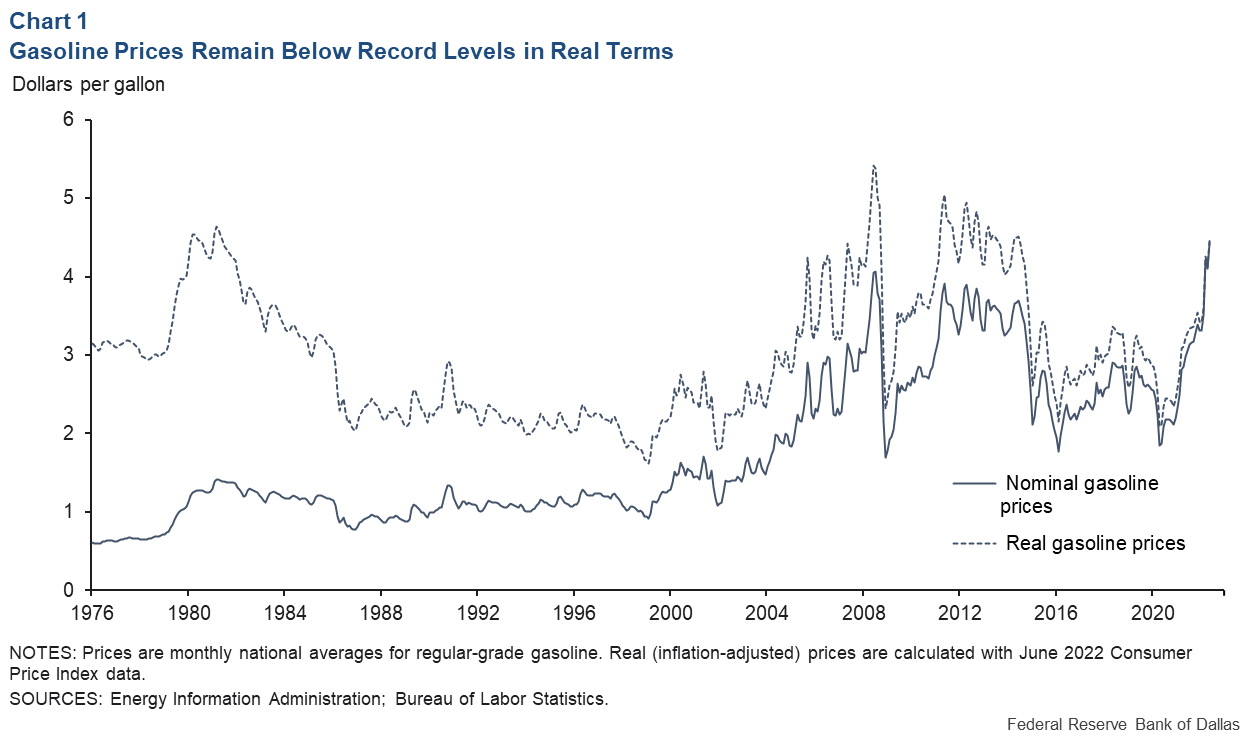

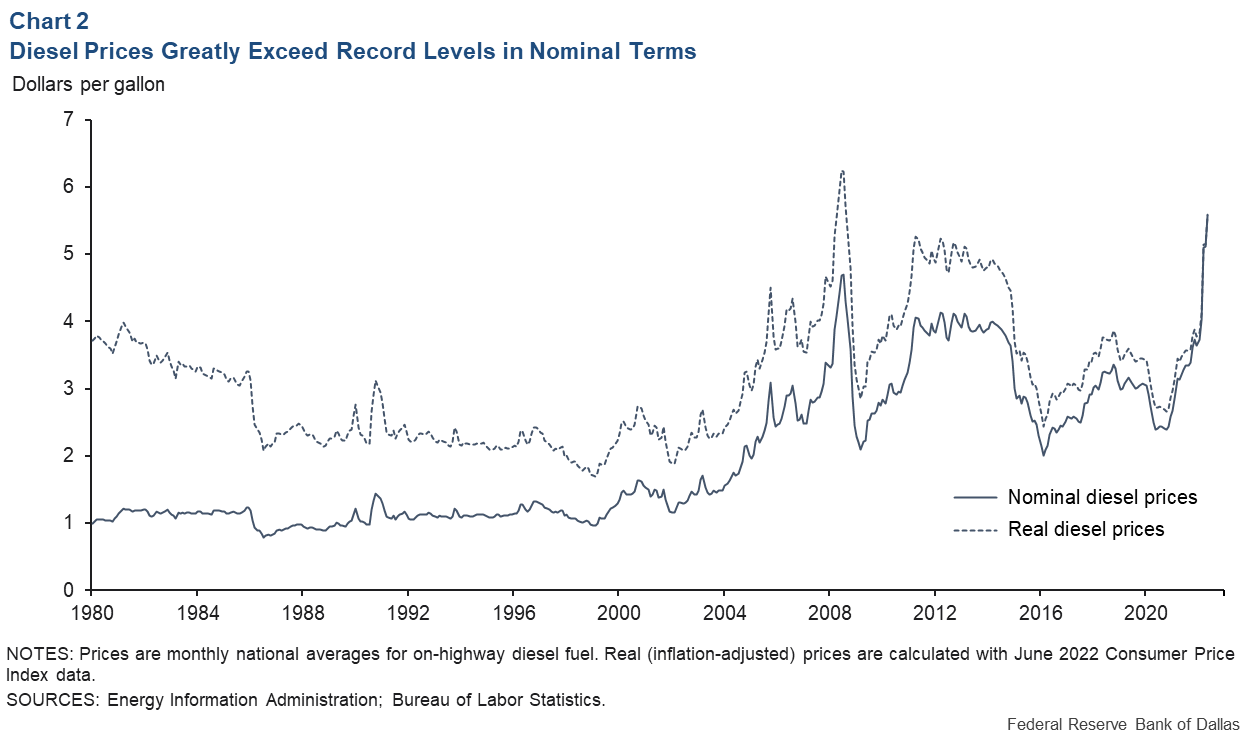

Gasoline and diesel prices in the U.S. are at record levels on a nominal (non-inflation-adjusted) basis (Charts 1, 2).

Much market commentary has focused on oil prices remaining far from record levels in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. WTI oil prices averaged $128 per barrel in July 2008, which in real terms is $169 today.

However, consumers buy refined products, not crude oil. The monthly national average for regular-grade gasoline, which reached $4.46 per gallon in May, is far below the 2008 peak of $5.35 in real terms, and gasoline prices between 2011 and 2014 were consistently at or above recent, early-summer levels. Though daily national average prices recently eclipsed $5 a gallon, prices could still rise much higher if one believes consumers experienced and, to some extent, withstood such prices before.

There are complications, though—inflationary pressures unrelated to fuel prices, declining real wages and the magnitude of this latest price shock. Additionally, a larger price spread between refined products and crude oil, particularly diesel, has amplified the impact of this shock relative to previous episodes.

These factors raise questions about whether U.S. fuel consumption can withstand higher prices for much longer. Without an adequate supply response arriving in the near term from either crude oil production or refining capacity, demand destruction is likely the only variable that can eventually cause the fuel price surge to slow and reverse.

Fuel has low price elasticity of demand

U.S. consumers historically only slowly reduce fuel consumption as prices increase. This is primarily because most consumers must drive to work, school, grocery stores and other destinations every day. Additionally, there are no scalable alternatives that can be immediately substituted. Using public transportation is an alternative mainly for those in dense urban areas, and buying a more fuel-efficient or electric vehicle at the first sign of higher pump prices is not an option for most.

Because of this, fuel demand is referred to as price inelastic, meaning as the price for the product increases, the quantity demanded decreases at a slower rate in percentage terms. For a price-elastic item, the quantity demanded would fall at the same rate or faster than the price increase.

With a supply-driven price shock like the current one, there is a risk due to price inelasticity that fuel prices could reach a level where consumers cut spending on other items, posing a risk to the broader economy.

Consumer memories are short

Though fuel prices have been much higher on an inflation-adjusted basis, consumers are unlikely to reference what they paid for fuel 10 years ago as a benchmark for current household budgeting. Vehicle purchases, work and commuting choices and travel plans are made with more recent prices in mind.

Consider someone who purchased a vehicle in December 2020, when gasoline prices averaged just $2.20 per gallon. Consumers tend to expect fuel prices to remain at or near that level during their ownership period.

The longtime best-selling vehicle in the U.S., the Ford F-150, has a combined fuel economy rating of 20 miles per gallon in its V-6 configuration for late-model years. With Americans driving an average of 13,474 miles in 2021, the F-150 owner’s annual fuel bill at $5 a gallon will rise $1,886, or about $157 each month, if the miles driven do not change.

Put another way, for a U.S. worker in the first quartile of income (the lowest 25 percent), 9 percent of earnings would go toward gasoline purchases now versus 4 percent a little more than a year earlier.

Problematic price premium for diesel

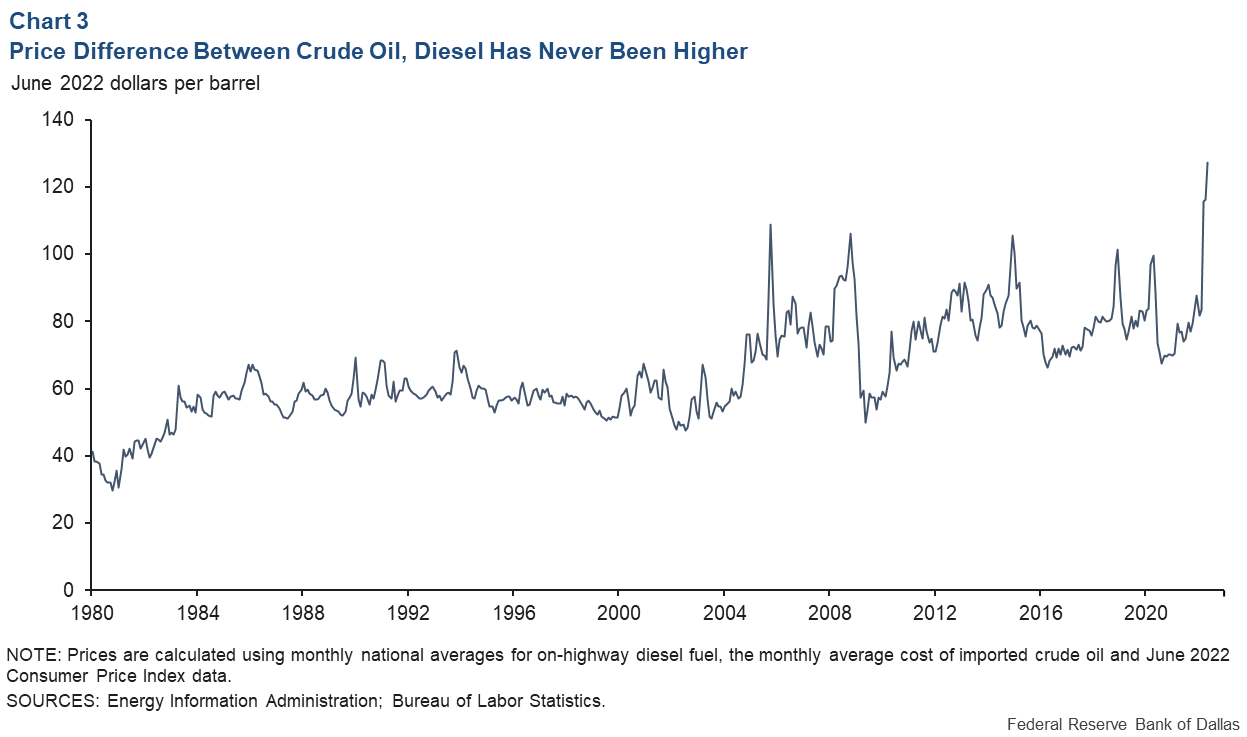

Distillates—the class of refined products that includes diesel, home heating oil and jet fuels—are in short supply globally and subject to surging prices. U.S. diesel prices have jumped 53 percent since December, while gasoline is up 34 percent. The main culprits: a reduction in U.S. refining capacity since the COVID-19 downturn in 2020, and the global scramble since February to replace sanctioned Russian diesel exports and crude oil (which renders more distillate than other types of crude oil).

The spread between on-road diesel and WTI prices has never been higher (Chart 3). At the current spread, diesel would average $7 per gallon nationally—well above the $5.57 average in May 2022—if WTI were to rise to $169 per barrel, the inflation-adjusted peak in 2008.

This price surge is most acutely felt by freight and agricultural end users, increasing the cost of bulk transportation, deliveries and food production. For a farmer who plants and harvests 1,000 acres of corn this year using conventional tilling, at an average of 5 gallons of diesel per acre, the fuel bill for that crop would be $27,500 today versus $16,400 in 2021.

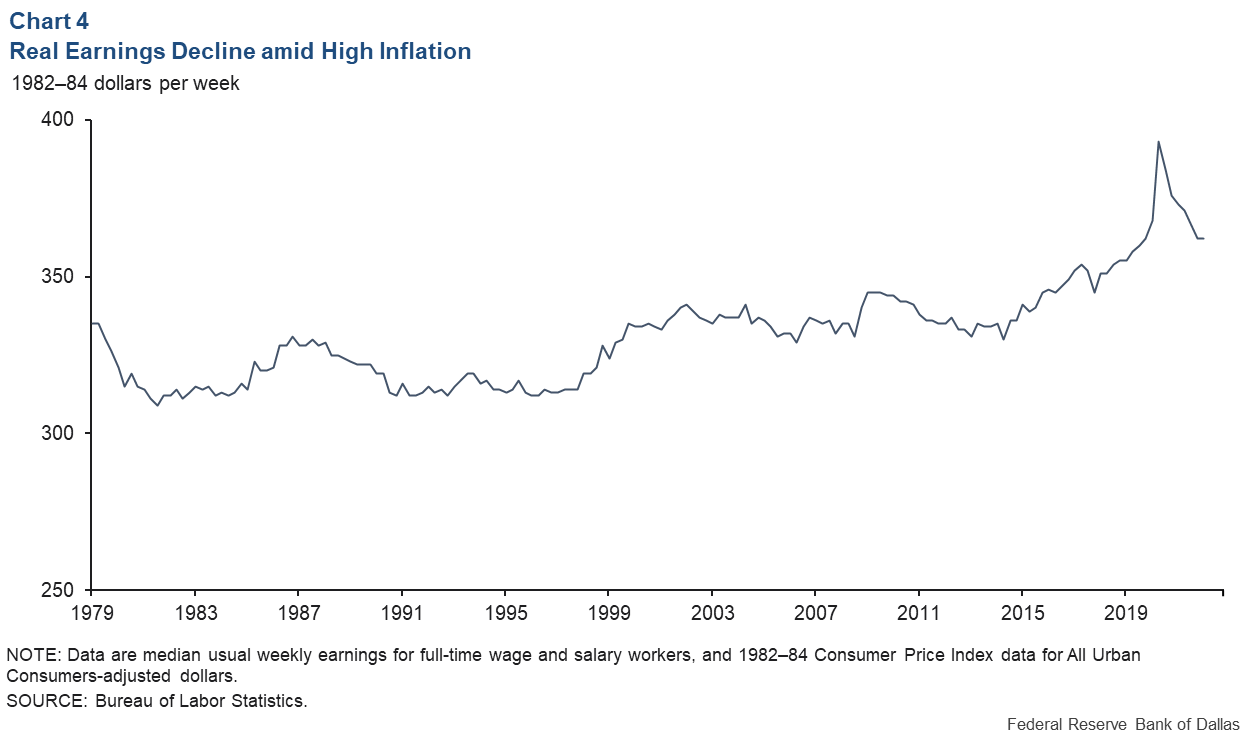

Fuel prices not the only inflationary pressure

The additional fuel expenditures might not be a problem if income growth were commensurate. However, wages have failed to keep pace with inflation since second quarter 2020. As a result, real earnings have declined at a pace not seen since 1979–81 (Chart 4).

Although real earnings are higher than during earlier episodes of high fuel prices, there is little room in most household budgets, particularly for those in the lowest quartile of income, to accommodate a 50 percent jump in fuel costs. The rapid decline in the personal savings rate over the past year could be considered evidence of tighter budgets.

U.S. fuel consumption bending, not breaking

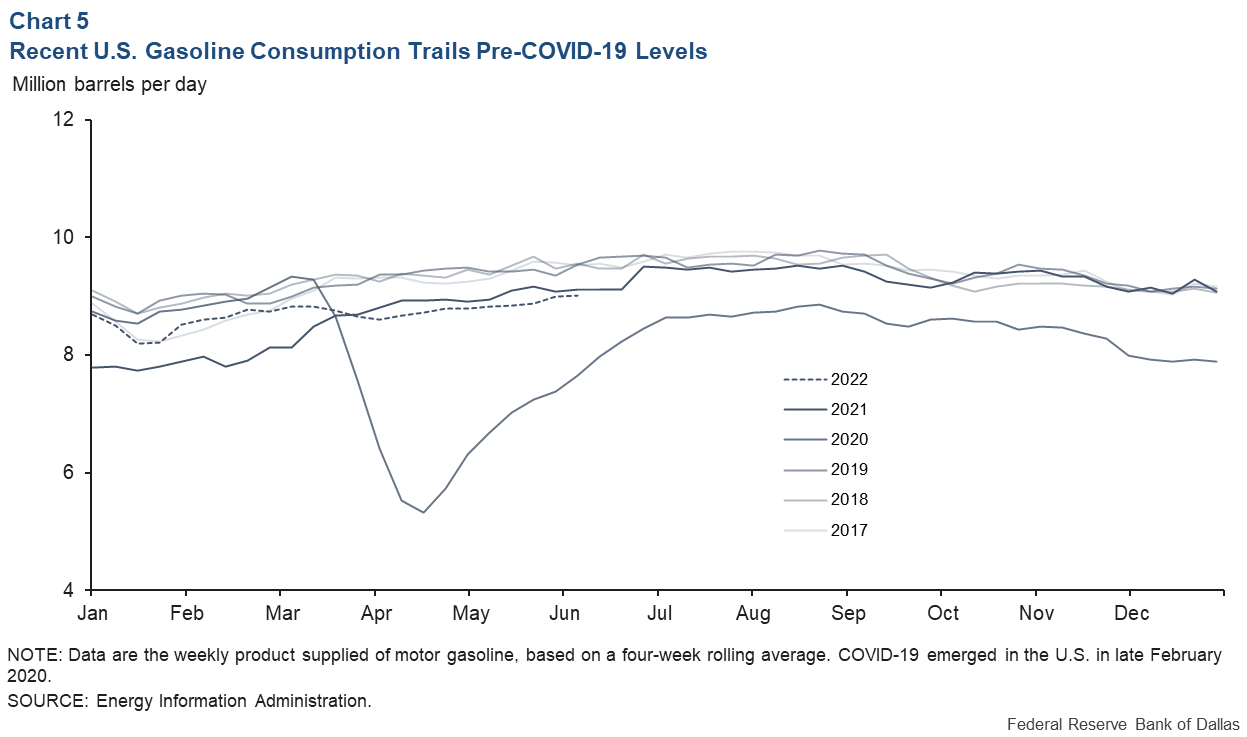

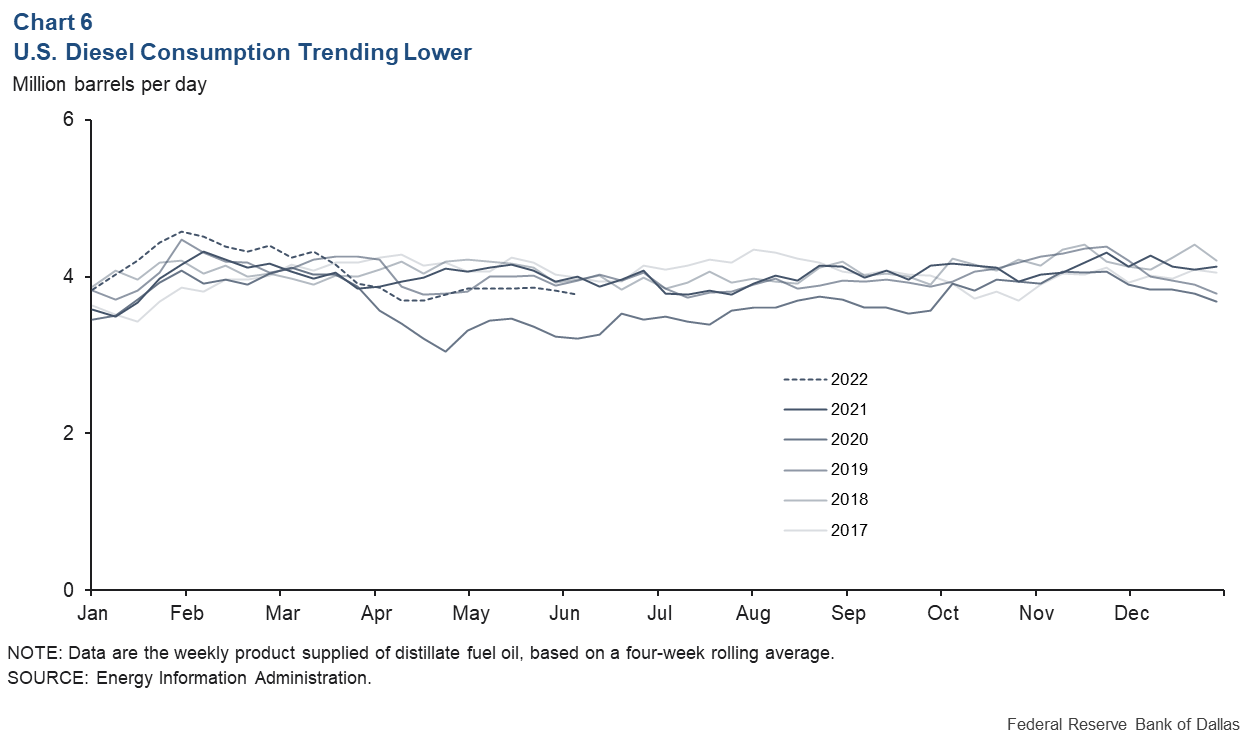

Still, U.S. fuel consumption has shown resilience. There has been no abrupt drop at today’s elevated prices. Gasoline demand has so far only come in below seasonal norms, while diesel consumption has trended lower after a strong start earlier in the year (Charts 5, 6).

Pent-up demand for travel (particularly foreign travel) amid easing COVID-19 restrictions could be a reason U.S. fuel consumption remains sticky. This may provide only a temporary uplift through August, when the summer travel season winds down.

At the same time, a proliferation of work-from-home options gives many workers the ability to reduce their commuting fuel use—which is roughly 30 percent of gasoline consumption—relative to pre-COVID-19 levels.

A continuation of the work-from-home trend could help reduce fuel demand and increase price elasticity going forward, though it is too early to fully assess the impact. Complicating matters are lower-wage workers, who are the least likely to have work-from-home options and are the most challenged by high fuel prices.

All told, fuel prices may be closer to consumers’ pain threshold than inflation-adjusted prices might suggest. And if prices climb higher, expect consumers to respond by cutting back on fuel consumption and overall spending sooner than later.