The connection between banking and sovereign debt crises

Simultaneous banking and sovereign crises are not uncommon in emerging countries and have been thoroughly detailed and studied in the economics literature. Economist Carmen Reinhart documents that out of 82 banking crises, 70 coincided with sovereign defaults. Using a different methodology, another study identifies 121 sovereign defaults and 113 banking crises, with 36 instances of the crises occurring together. Sovereign and banking crises are more common in emerging economies that are highly indebted, economists Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas and Maurice Obstfeld note.

In this article, I attempt to show in how sovereign debt crises can amplify banking problems.

Modeling the set-up for a ‘diabolic loop’

A recent working paper I co-authored with Cesar Sosa-Padilla and Zeynep Yom studied the relationship between banking and sovereign crises and the optimality of bank bailouts. We build a model of banking and sovereign crises where sovereign debt crises can lead to banking crises, and banking crises can lead to governments bailing out the banking sector, producing increased sovereign default risk.

Bailouts can help relax financial frictions and boost output during banking crises but also increase government debt. That, in turn, can lead to sovereign default risk, creating a “diabolic loop.” We use the model to investigate whether allowing governments to bail out banks is optimal.

In the model, a banking crisis leads to higher and more volatile interest rates on government debt. The model also features banking crises that are linked to sharp reductions in national output—GDP, for example—and spikes in sovereign yields. High-debt governments that experience a banking crisis face deeper and longer recessions and even higher interest costs.

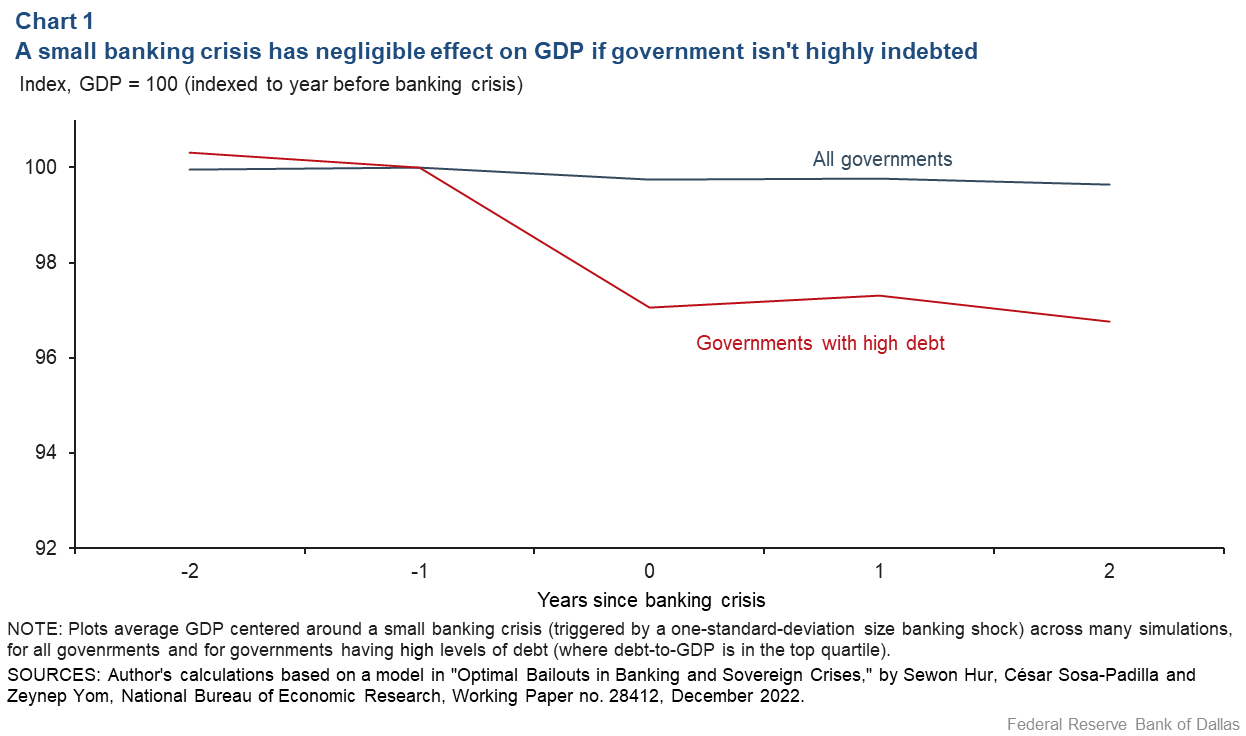

We can simulate the effects of a banking crisis under different scenarios using the model (Chart 1). The dark line in Chart 1 shows that a small banking crisis (a one-standard-deviation shock to bank capital, one we might observe every few years) affects GDP little on average. The effect is greater (a 3 percent reduction of GDP) when the government is highly indebted—when its debt level exceeds that of three-quarters of all other governments (red line).

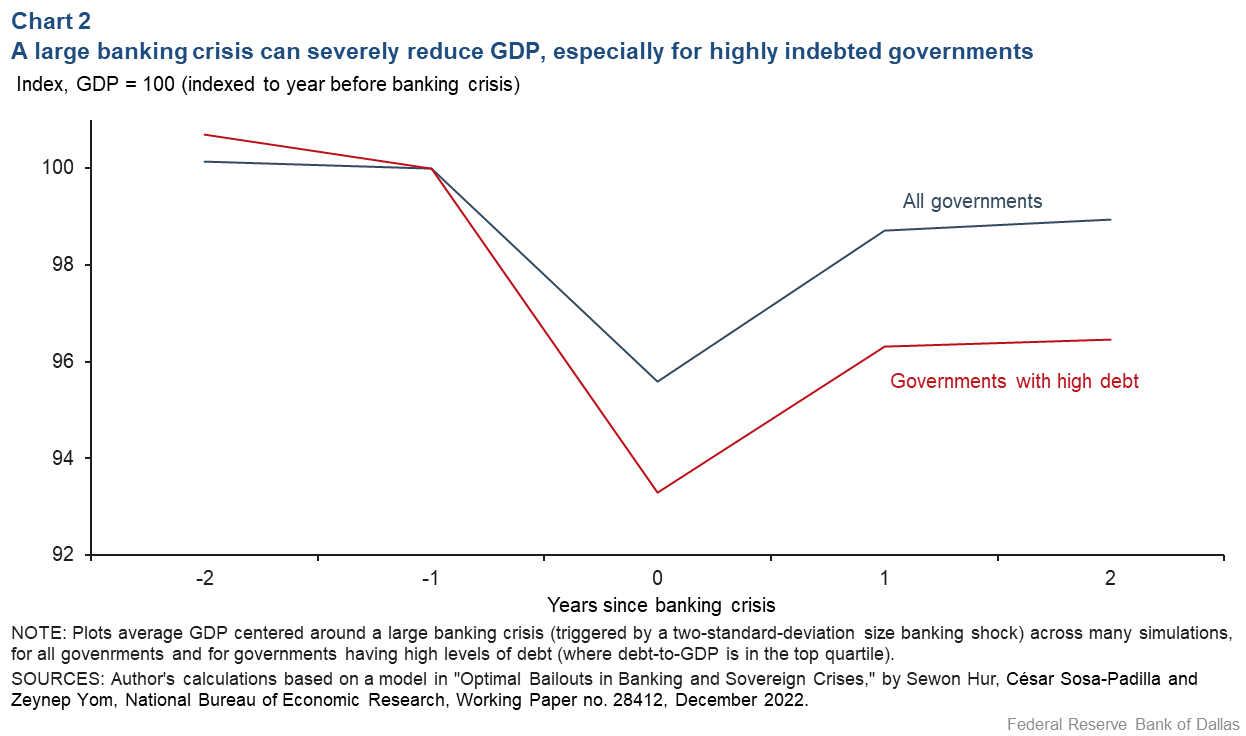

Countries with higher levels of government debt—typically, those with some default risk— experience a more severe recession (declining GDP) because they have less fiscal space to bail out the banking sector. Larger banking crises (a two-standard-deviation shock to bank capital, one that could occur once every 20 years) can significantly affect GDP, both on average and conditional on high debt (Chart 2). The effects are even more pronounced (a more than 6 percent reduction in GDP) if the shock occurs when a nation’s indebtedness exceeds that of three-quarters of the other governments.

Weighing the impacts of banking sector intervention

Finally, the model suggests that governments must carefully weigh the longer-term consequences of intervening in the banking sector during crises.

Bailouts may provide immediate relief, but they come with a trade-off: Although they can boost bank liquidity and output during banking crises, paying for bailouts may also require additional borrowing, thus leading to heightened government default risk and increased long-term borrowing costs.

Ultimately, banning bailouts may lead to better long-term outcomes by breaking the loop between banking and sovereign crises and creating better borrowing opportunities for governments.

If governments commit to no future bailouts, private lenders would be willing to lend to governments at a lower rate, knowing that the governments would be less likely to fall into sovereign default crises. As a result, the governments would be able to borrow less expensively with less chance of default. Such gains may well outweigh the benefits of bank bailouts.

About the Author

Sewon Hur is a senior research economist in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.