Refilling the Strategic Petroleum Reserve offers chance to recalibrate its size

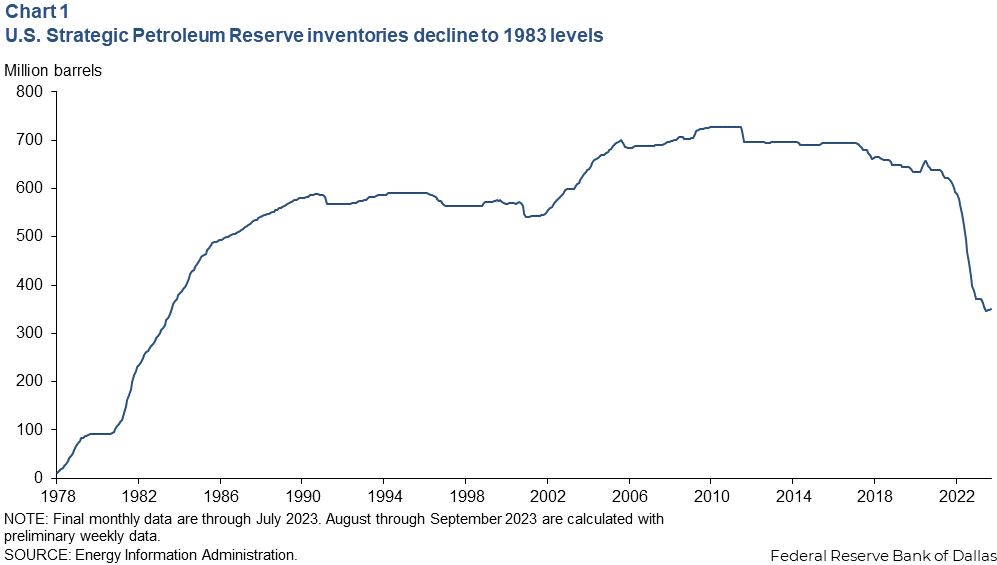

A series of emergency drawdowns, exchanges and planned sales since 2020 have reduced crude oil inventories held by the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) to a 40-year low (Chart 1).

Calls to fully refill the SPR in recent months following this dramatic reduction raise important questions. First, because of a significant decline in U.S. oil imports over the past decade, does the SPR need to be as large as it once was?

Second, with U.S. refineries requiring a combination of crude oil grades produced domestically and abroad, what might be an appropriate mix of oils for the SPR? And finally, what amount of SPR refill is possible with available funding and how much more might be required?

An analysis finds that a complete refill of the SPR may be unnecessary depending on policy objectives. Instead, the SPR could be recalibrated at a lower absolute level of inventory for the type of supply disruption it was originally intended to mitigate.

Creation of SPR dates to 1973 Energy Crisis

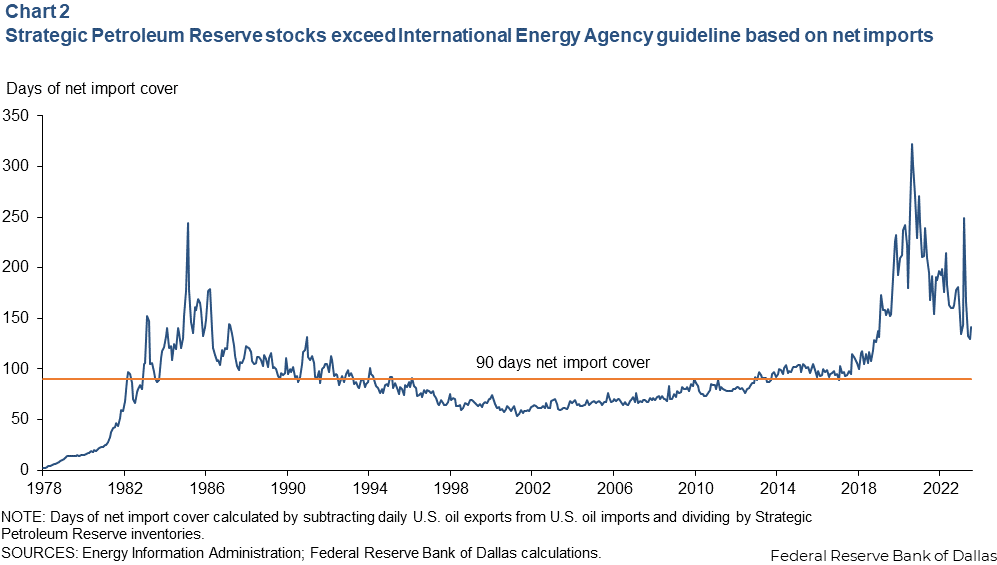

Among many policy responses to the 1973 OPEC oil embargo was creation of the International Energy Agency (IEA). IEA members are obliged, but not legally required to hold strategic inventories equivalent to at least 90 days of net oil imports (exports minus imports) for use in the event of a supply emergency.

To meet its obligation, the U.S. constructed its SPR in a series of underground salt caverns along the Gulf Coast near the country’s largest refining center, interstate pipelines and loading terminals. Filling began in 1977, and the reserve reached a peak of 727 million barrels (mb) in 2009.

In recent years, surging domestic shale oil production diminished U.S. oil import demand and led to the repeal in 2015 of an embargo-era ban on U.S. oil exports. Consequently, because imports declined and exports grew, the size of the SPR as measured in net import days’ cover substantially increased (Chart 2).

Policymakers made note of the size of the SPR relative to import needs. This made selling a portion of the SPR an attractive source of funding for infrastructure and other federal spending priorities. Starting in 2015, Congress passed a series of bills authorizing the sale of 271 mb of SPR crude between 2017 and 2028 to raise funds.

With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in March 2022, President Joe Biden ordered a series of unprecedented emergency sales and exchanges of SPR crude. (Exchanges are arrangements for a refinery to borrow SPR oil and replace it in full plus a small additional, premium amount at a future date).

Anticipating disruption of Russian oil flows and a surge in fuel prices, the administration released 217 mb from December 2021 through October 2022. With these emergency actions and previously mandated congressional drawdowns, SPR stocks in September 2023 totaled 350 million barrels, the lowest level since 1983.

Refiners need a variety of crude oils

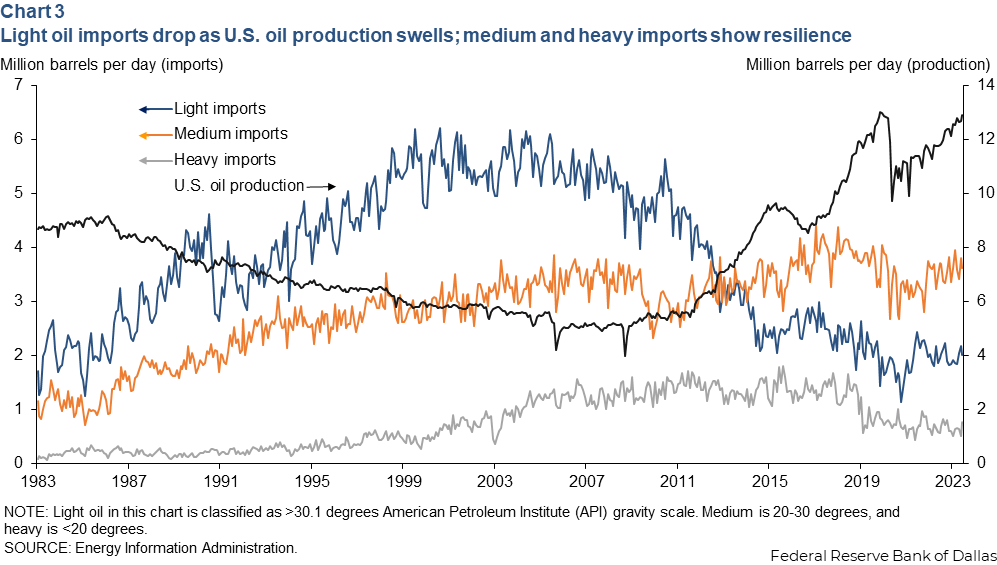

U.S. refineries require a mix of crude oils to produce an optimal balance of refined products. Crude oil quality varies by density (or viscosity, noted as heavy, medium or light) and sulfur content (labeled sweet or sour). In general, certain fields and regions tend to produce specific grades of crude oil. Importantly, the ratio of refined products that can be rendered from each grade can vary significantly.

U.S. oil production growth since 2010 has been composed entirely of light, sweet crude. As refineries recalibrated to process as much light, sweet oil as possible, they slashed imports of similar grades. But imports of heavy and medium sour crude oils have remained comparatively stable because refineries still need these crudes that are less plentiful in U.S. fields (Chart 3).

Funding, parameters could change for SPR refill

Should a foreign supply disruption develop, U.S. refineries are more likely to lose access to overseas medium sour crude oils than light sweet domestic crude and the medium and heavy sour varieties plentiful in Canada. Recognizing this, the Department of Energy is targeting medium sour barrels as it refills the SPR.

Proceeds from previous emergency sales and appropriations from Congress pay for purchases for the SPR. The 180 mb sale in 2022 generated $17.2 billion for the SPR account, according to the Department of Energy.

However, in December 2022 Congress canceled several previously mandated SPR sales for 2024–27 to prevent further drawdown of the SPR. A total of $12.5 billion from 2022 emergency sales was diverted from the SPR account to cover the resulting federal budget shortfall. That left $4.7 billion to refill the SPR, of which $452 million was spent to acquire 6.2 mb in June 2023.

The Department of Energy announced in October 2022 it would prefer to buy crude oil to refill the SPR at a range of $67 to $72 a barrel. Should oil prices return to those levels, another 59 million to 63 million barrels could be acquired without further congressional appropriations. Additionally, at least 27 mb will be deposited because of the SPR exchange authorized in late 2021. This would bring the SPR to between 436 mb and 440 mb.

Perspectives vary on SPR inventory levels

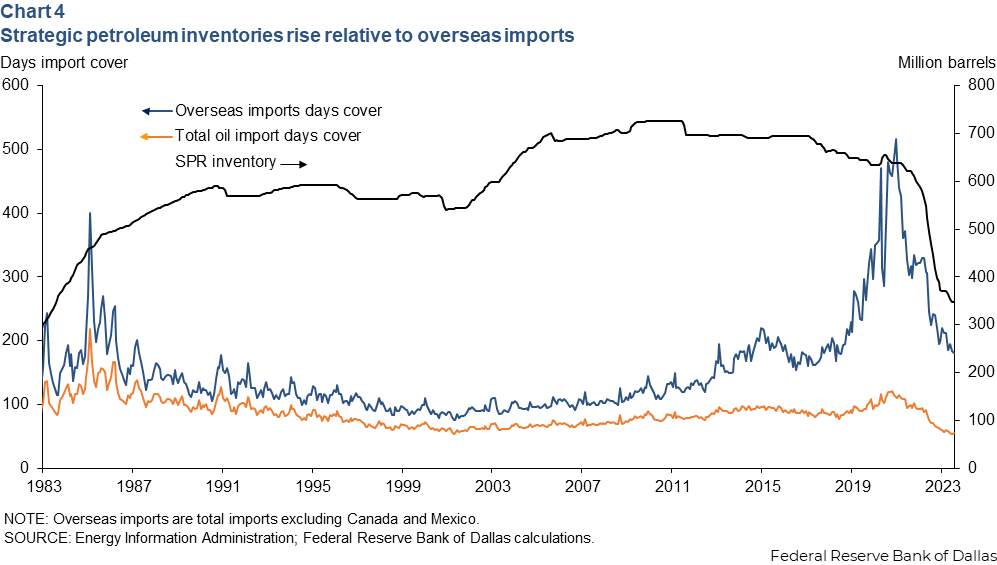

The U.S. government has historically followed IEA guidelines calling for 90 days net import cover in the SPR, a level it currently greatly exceeds. However, net import cover could now be considered an inadequate measure for strategic inventories, as the U.S. still requires varying crude qualities and volumes that the IEA’s standard doesn’t fully capture. A different basis for measuring SPR inventories that still complies with the 90-day guideline would be more appropriate.

When considering only overseas imports that are arguably more prone to disruption than other sources, SPR inventories are roughly double their historic average, even at today’s low absolute level. On the other hand, inventories sit at historic lows today relative to gross oil imports—the equivalent of 55 days of import cover (Chart 4).

Risks to U.S. oil supply have changed

It is up to policymakers to determine how to weigh geopolitical risks that threaten global oil supply, how much funding to appropriate, and, therefore, how big the SPR should be. However, focusing narrowly on import requirements, crude oil quality and supply risks, provides an alternative SPR framework to the IEA’s standards.

While current available funding to refill the SPR appears sufficient from an overseas import perspective, one could argue geopolitical risks and uncertainties in the global oil market are more likely to rise than fall. This supports the case for an SPR larger than the 440 mb level it is heading toward.

To approach pre-2022 levels of gross oil import days cover, SPR stocks would need to rise to at least 550 mb. This would require several billion dollars in additional expenditures.

However, gross imports include Canada and Mexico, two countries that pose comparatively low disruption risk and maintain robust economic ties with the U.S. At the same time, while imports from Canada and Mexico remain comparatively stable, they are still exposed to natural disaster risks for which U.S. policymakers should account.

Considering whether to set a new standard

While the SPR peaked at 727 mb and held more 600 mb just two years ago, current and prospective oil market conditions indicate the U.S. is unlikely to require that level of strategic inventories again.

Moreover, refilling the SPR does not appear to be as pressing an emergency as the drop in absolute levels initially suggests. Rather, an appropriate target for the refilled level might be above what current funding allows but well below the maximum capacity of the reserves.

About the author

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.