How do reciprocal deposit networks interact with deposit insurance?

Reciprocal deposit networks allow bank customers to split large deposits among multiple accounts across several banks to obtain Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) coverage of up to $250,000 for each account.

Without reciprocal deposit networks, the FDIC insurance coverage would be capped at the $250,000 account limit. Reciprocal deposit networks are designed to increase the total amount eligible for FDIC deposit insurance.

In recent years, growth of the networks has accelerated, prompting a re-evaluation of the existing deposit insurance framework and raising at least three questions.

- Is the current level of deposit insurance optimal?

- Are reciprocal networks the best way to provide additional insurance to depositors?

- Should regulatory agencies favor a level playing field for the most frequent users of the networks, small- and medium-size banks, relative to large banks that benefit from what appears to be an implicit deposit guarantee?

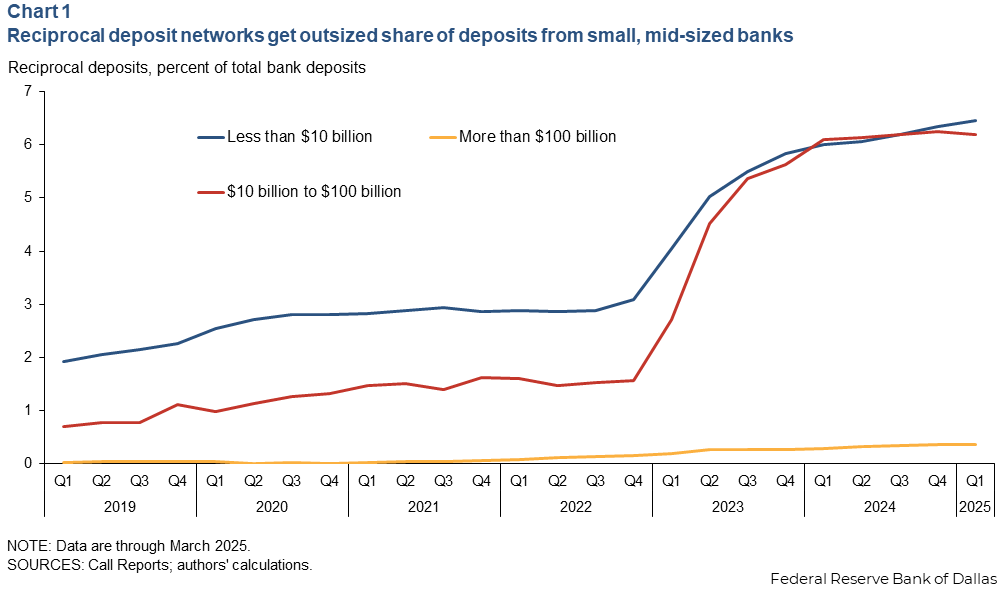

The networks’ share of deposits has rapidly grown in the postpandemic period. Deposits totaling $422 billion were in a reciprocal deposit network at the end of first quarter 2025.

Reciprocal deposits represented 6.47 percent of total deposits for banks with less than $10 billion in assets in the first quarter, up from 6 percent at the end of first quarter 2024. Among institutions with assets of $10 billion to $100 billion, such deposits accounted for 6.2 percent of total deposits as of March 31, 2025, down only slightly from year-end 2024 but up from 6.1 percent at the end of first quarter 2024 (Chart 1).

FDIC deposit insurance level might not be optimal

The FDIC’s deposit insurance fund generally covers most deposits up to predetermined limits. Economists Eduardo Davila and Itay Goldstein discuss a banking model in which the level of deposit insurance is optimally determined by balancing the marginal gain from reducing the likelihood of bank failures against the expected marginal social cost of making insured depositors whole when banks fail.

The authors calibrate the model on a representative bank and find that when the standard account insurance limit increased in 2008 from $100,000 to $250,000, the level of deposit insurance could have been set even higher and still provided optimal coverage.

The economists’ model offers an interesting thought experiment. Calibrating the model on different banks (as opposed to a representative bank) would give different levels of optimal deposit insurance depending on how confident depositors are about the profitability of the banks, what interest rates the banks offer and the assets the banks hold.

Combinations of these parameters might justify a higher level of insurance for some banks and a lower level for others. Thus, while the aggregate level of deposit insurance might or might not be optimal, the demand for insurance at local institutions varies greatly. We can think of reciprocal networks as a mechanism to allow investors to move toward their level of desired insurance.

Reciprocal deposits may be cheaper than raising deposit insurance limits

Reciprocal deposits are a technologically aided solution to a problem that depositors have always faced: how to open accounts at multiple banks to increase FDIC insurance coverage. The networks solve this problem by providing a placement service in exchange for a fee.

The cost of accessing these services varies across networks, averaging roughly 12 to 15 basis points. (One-hundred basis point equals 1 percentage point.) The $422 billion in reciprocal deposits imply an annual cost of $500 million to $600 million.

If the desired outcome was simply to increase the size of insured deposits by the total amount currently placed in reciprocal deposits without considering which depositors would gain access to additional insurance, it could be more economical to increase the FDIC insurance limit to approximately $375,000. Thus, the cost of paying some portion of the $500 million in network fees could be avoided.

Would this deter the demand for reciprocal deposit services? Probably not. Most deposits placed in the networks are concentrated in small banks and are often for very large amounts. In other words, the demand for additional insurance is bank and depositor specific. An insurance limit increase from $250,000 to $375,000 would not disincentivize these depositors' use of reciprocal networks.

Because of the way the Federal Deposit Insurance Act provides for the funding of the deposit insurance fund, addressing the concerns of such large depositors by changing the FDIC deposit insurance limits would be expensive. Insuring every depositor currently enrolled in one of the reciprocal deposit networks would require an FDIC insurance limit so high, that only the largest deposit accounts in the system would not be covered.

Such an expansion would be costly: $15 billion in annual bank-paid fees to maintain the insurance fund in line with requirements of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act.

Essentially, as long as reciprocal deposits continue to experience moderate growth, allowing the networks to exist while continuing with the current statutory level of FDIC deposit insurance appears to be the most economically feasible strategy.

Leveling the playing field might be possible

The existing framework creates an imbalance between banks of different sizes. On the one hand, small banks allow depositors to access reciprocal networks and, by and large, absorb the cost. They typically do not pass along the network fees to customers.

On the other hand, it is often assumed that any large bank distress could trigger the invocation of the systemic risk exception. This occurred following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and subsequent disruption in March 2023, when all deposits of the failed bank were guaranteed. In such cases, the FDIC subsequently recovers the cost of such an intervention ex post from a special assessment to banks that share similar characteristics to the one failing. In the 2023 case, a special assessment was levied against banks with more than $5 billion in total assets.This creates an asymmetry. To stabilize their depositor base, small banks pay ex ante to place deposits into reciprocal networks; large banks, on the other hand, pay to replenish the deposit insurance fund only after a large bank fails.

One way to level the playing field would be to charge large banks ex ante, as suggested by economists Viral Acharya, Joao Santos and Tanju Yorulmazer. The Federal Deposit Insurance Act does not offer such a solution, and, thus, legislation would be required to, among other things, specify how to measure systemic risk exposure at the bank level.

Another possibility, consistent with the current assessment methodology, would be to recognize during the regular risk-based assessment that banks accessing reciprocal deposit networks are safer than those that do not access the networks, and they are less likely to pose a risk of loss to the deposit insurance fund. These banks’ network access appears to provide various benefits. Among them, economists Edward Kim, Shohini Kundu and Amiyatosh Purnanandam find reciprocal deposit network access helps banks stabilize their depositor base.

About the authors