Shale oil boom gave Permian Basin a second life

During the first four months of 2012, the average monthly price of benchmark West Texas Intermediate crude oil stayed stubbornly above $100 per barrel, creating anxiety then, as now, about higher energy prices.

During the first four months of 2012, the average monthly price of benchmark West Texas Intermediate crude oil stayed stubbornly above $100 per barrel, creating anxiety then, as now, about higher energy prices.

The Permian Basin, home to many of America’s oldest oil fields, covers 75,000 square miles of West Texas and southeastern New Mexico. Discovered in 1921, the formation has produced more than 40 billion barrels of oil, including much of the oil used during World War II. Until recently, the Permian Basin’s biggest challenges were to slow the loss of production—which began ebbing in 1973—while squeezing out the last 30 billion barrels of “mobile” oil as economically as possible. That was before innovation, technology and $100-per-barrel oil offered the aging fields a new future.

The breakthrough arose in the Midland area’s Spraberry oil field, among the Permian Basin’s most venerable locations. Spraberry formations were fractured for decades, usually in one or two zones, for vertical wells. The innovation: drilling vertically while emulating the multistage fracturing typical of horizontal wells. The result spawned a boom in the eastern Permian Basin in 2005, reversing years of decline.

The Permian Basin’s second chance at new life parallels earlier development of the Eagle Ford in South Texas. Horizontal drilling and fracturing could produce oil from shale—and the western Permian Basin is rich in shale. The Delaware Sub-basin encompasses the Hobbs area of southeastern New Mexico and four counties of West Texas.

Shale development is just beginning in the Delaware. A Texas General Land Office lease auction in April 2011 brought a bid of $3,264 per acre for 30,000 acres, compared with an average bid of $906 per acre six months earlier.

Update: By 2016, as the industry emerged from the largest oil bust since 1986, business-to-business acreage transactions in the Permian ranged from $7,000 to $58,000 per acre. Two years later, some positions sold for as much as $70,000 an acre, according to estimates. In 2021, after the COVID-19 bust, large acquisitions were being priced at closer to $10,500 per acre.

Partly because these developments are relatively new, production data don’t yet reflect the magnitude of the changes. Oil production in the Delaware during 2011 was 13 million barrels above that in 2008, while natural gas production declined significantly.

Update: Oil production in the Delaware reached 751.2 million barrels in 2019. Natural gas output increased 2.43 trillion thousand-cubic feet (Mcf) from 2008 to 2019. In 2020, the Delaware Sub-basin produced 660 million barrels of oil and 2.96 trillion Mcf of natural gas.

As production has grown in the Eagle Ford and Bakken oil shale regions, a shortage of infrastructure to transport the product to market has been a key constraint.

Update: By 2022, total Permian Basin takeaway capacity had expanded to more than 6 million barrels per day from less than 2 million a decade prior.

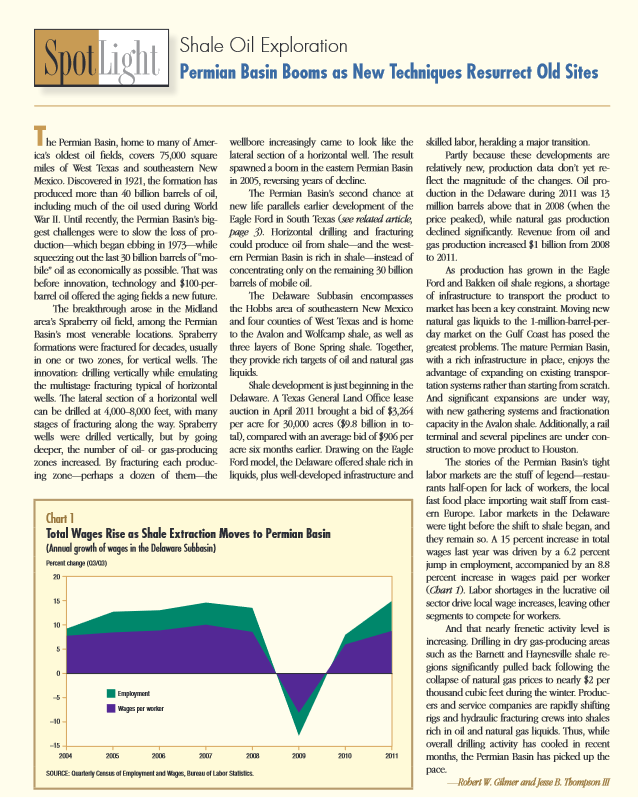

The stories of the Permian Basin’s tight labor markets are the stuff of legend—restaurants half-open for lack of workers, the local fast-food place importing wait staff from eastern Europe. Labor markets in the Delaware were tight before the shift to shale began, and they remain so.

Update: On average, the unemployment rate was more than 1.3 percentage points lower in the Midland–Odessa area than the state in the 2010s—including during the disastrous 2015–16 oil bust. In December 2021, metro unemployment was 5.6 percent versus 5 percent statewide.

About the Author

Jesse Thompson

Thompson is a senior business economist in the Houston Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2022/swe2201.