Middle East geopolitical risk modestly affects inflation and inflation expectations

Geopolitical risk spiked during the Israel-Iran aerial bombardment in June 2025. In a matter of weeks, the daily price of benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil rose from $67 per barrel to $76 in mid-June. It then retreated to near preconflict levels following a ceasefire announcement.

Polymarket, an online platform for investors to place bets on future events, as of July 30 priced a 14 percent probability that Iran would close the shipping channel through the Strait of Hormuz in 2025. This is similar to the pricing before the conflict and much lower than the 60 percent probability during the height of Israel-Iran hostilities.

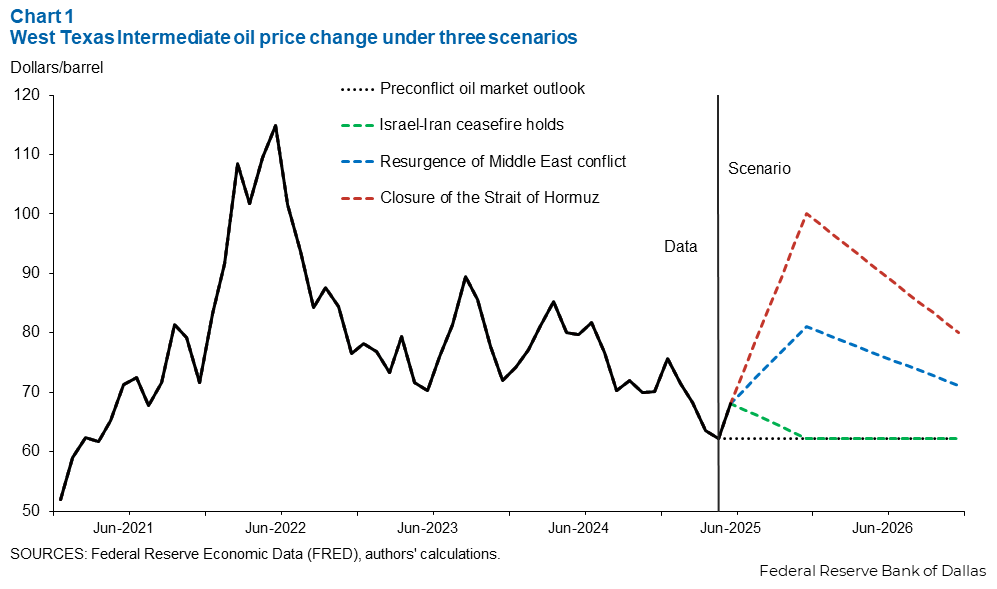

This oil market turbulence has triggered renewed interest in how geopolitically driven oil and gasoline price shocks affect U.S. inflation and inflation expectations. We conducted a scenario analysis of alternative oil price paths for the next 18 months. It uses a structural vector autoregressive model, a tool to explore the relationship of variables over time, to assess their effects on U.S. inflation and inflation expectations.

Our analysis shows limited effects in a severe scenario in which West Texas Intermediate (WTI) reaches $100 per barrel by year-end due to rising geopolitical risk. This estimate is based on data from 1990 to mid-2025. Over this period, gasoline and oil price shocks do not persistently affect U.S. headline inflation or short-term inflation expectations. In addition, the effects on core inflation (prices excluding food and energy) and long-term inflation expectations are muted.

Three scenarios for the price of oil

To assess the potential impact of Middle East-driven oil price shocks on U.S. inflation and inflation expectations, we consider three scenarios (Chart 1).

The baseline scenario (Israel-Iran ceasefire holds) is the most likely. Under this scenario, the monthly WTI price, after rising in June 2025 to $68 per barrel, reverts to $62–$63 by year-end 2025, as oil futures data suggest. This scenario assumes resolution of the Israel-Iran conflict, and the oil market returns to its preconflict state.

The second scenario (Closure of the Strait of Hormuz) reflects a major oil supply disruption. Under this scenario, the Strait of Hormuz, the vital Persian Gulf shipping route along Iran’s southern border, would close, halting 20 percent of global oil supply flows. In this case, rising geopolitical risk and eventual disruption in December 2025 would drive the WTI price to peak at $100 per barrel. Oil prices then moderate, reflecting the likelihood that the closure would be temporary.

The third scenario (Resurgence of Middle East conflict) is an outcome falling between the first two. In this case, oil prices increase to $81 by year-end 2025 and return to $70 by the end of 2026.

Structural model of inflation and inflation expectations offers insights

The model used for the scenario analysis builds on the work of Lutz Kilian and Xiaoqing Zhou (2022a; 2022b; 2023; 2025). Several studies have shown that oil price fluctuations impact U.S. inflation mainly through changes in gasoline prices. Our model includes gasoline prices to identify such shocks. The identifying assumption is that monthly gasoline price changes are predetermined with respect to U.S. economic conditions, a standard assumption in the literature and supported by evidence in Lutz Kilian and Clara Vega (2011).

The model also includes headline and core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation, as well as the University of Michigan survey of one-year and five-to-10-year inflation expectations, with six lags for each of the model variables. Our data cover the period from April 1990, when the long-term inflation expectations became available, to May 2025, the month before the recent Israel–Iran hostilities.

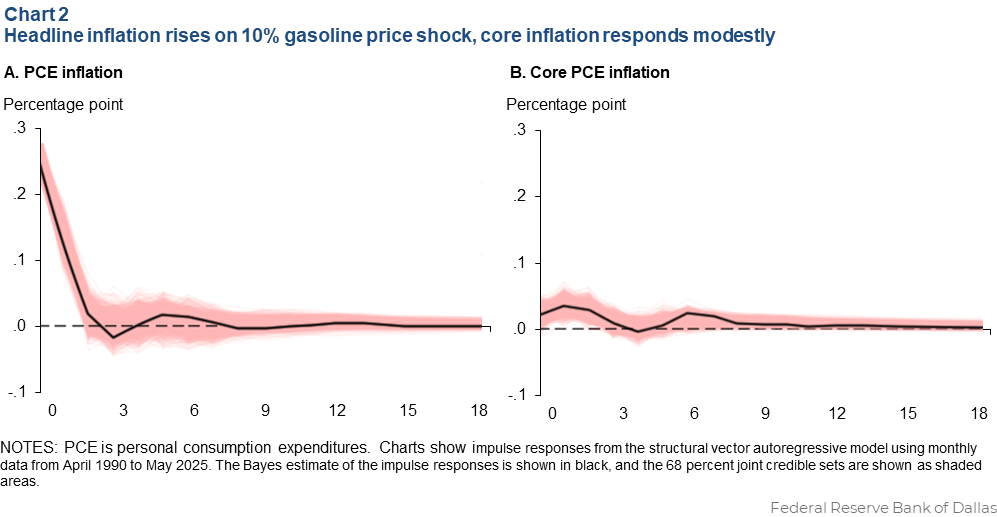

Chart 2 shows the effects of a 10 percent positive gasoline price shock on inflation. Headline PCE inflation increases by about 0.2 percentage points in the first month, but the effect quickly fades after two months.

The effect on core inflation is small, about 8 basis points (100 basis points equal 1 percentage point) in the first three months before becoming insignificant, indicating limited second-round inflationary effects.

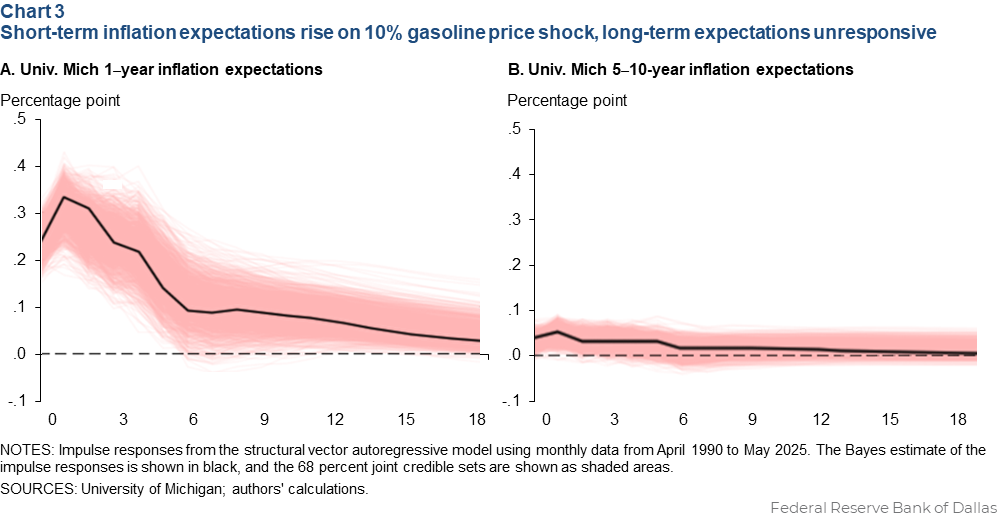

Chart 3 shows the effects on inflation expectations. One-year inflation expectations increase 0.3 percentage points in the first few months and then decline, becoming insignificant after six months.

Long-term inflation expectations display a muted response. These patterns are robust to using alternative model specifications and alternative inflation and inflation expectations measures.

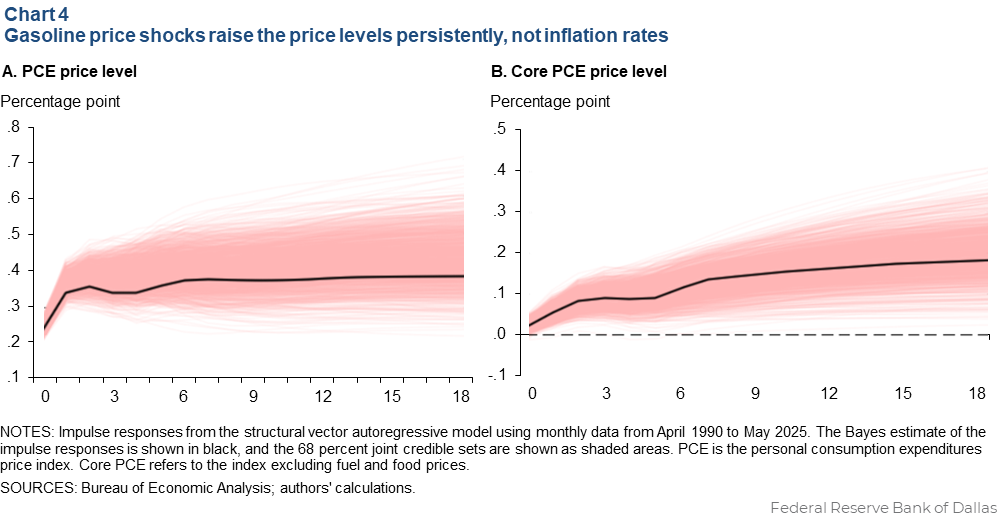

The responses of headline and core inflation may seem at odds with some recent studies claiming persistent and large inflationary effects using data and models similar to ours. These studies tend to conflate the response of the inflation level (defined as the cumulative price response) with the response of the inflation rate. As Chart 4 illustrates, a one-time gasoline price shock persistently raises the price level in our model, as gasoline is part of the consumer basket. However, it does not cause the inflation rate to increase persistently.

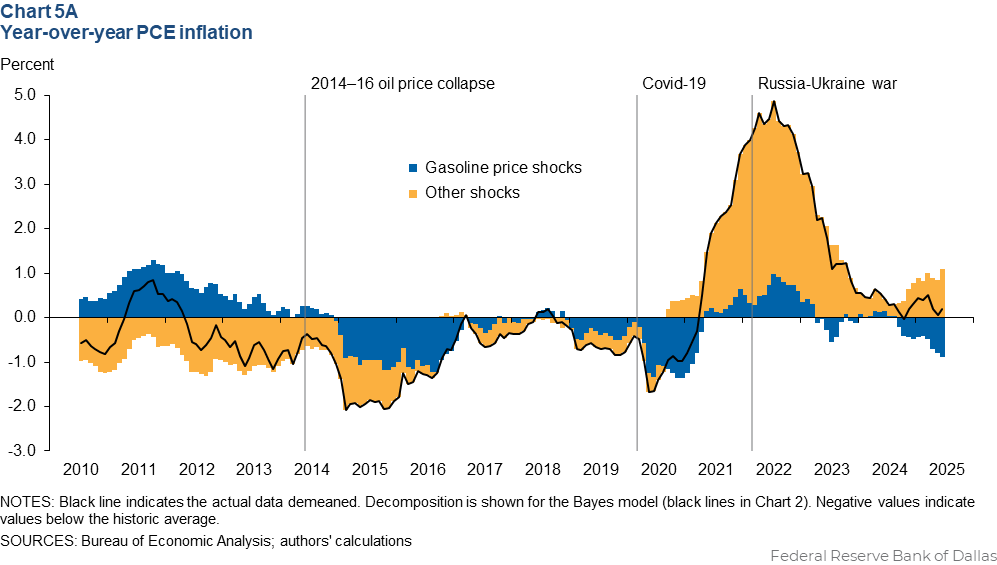

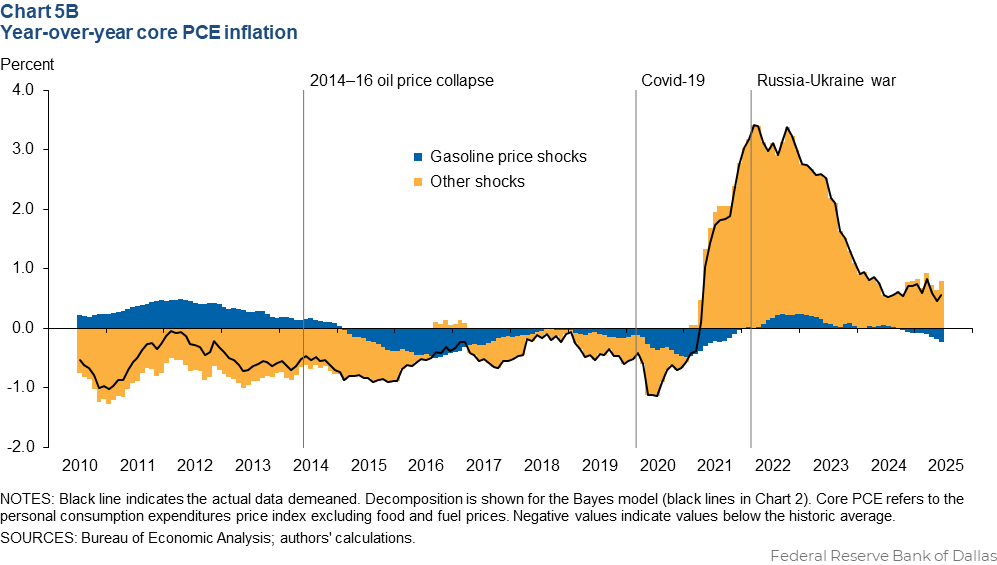

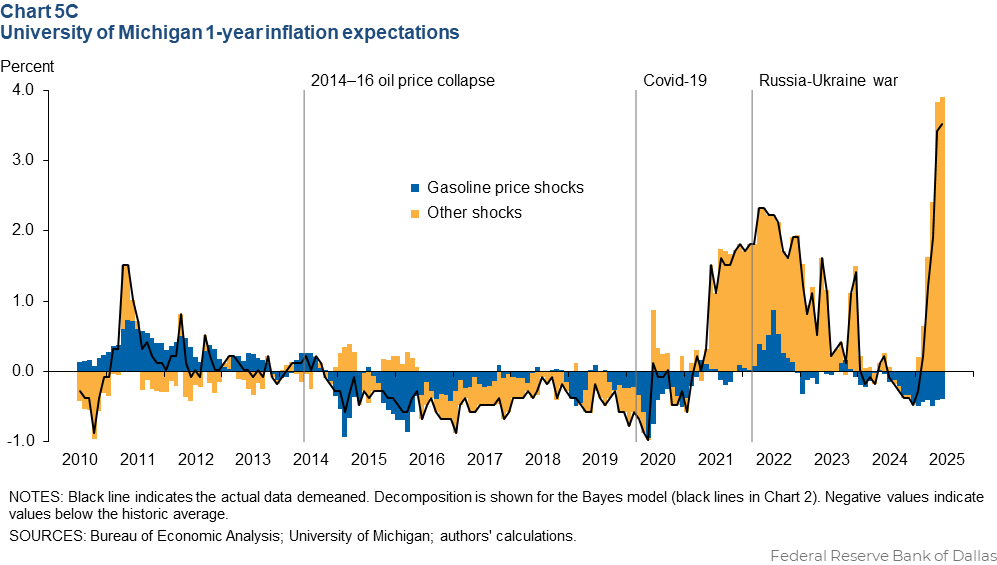

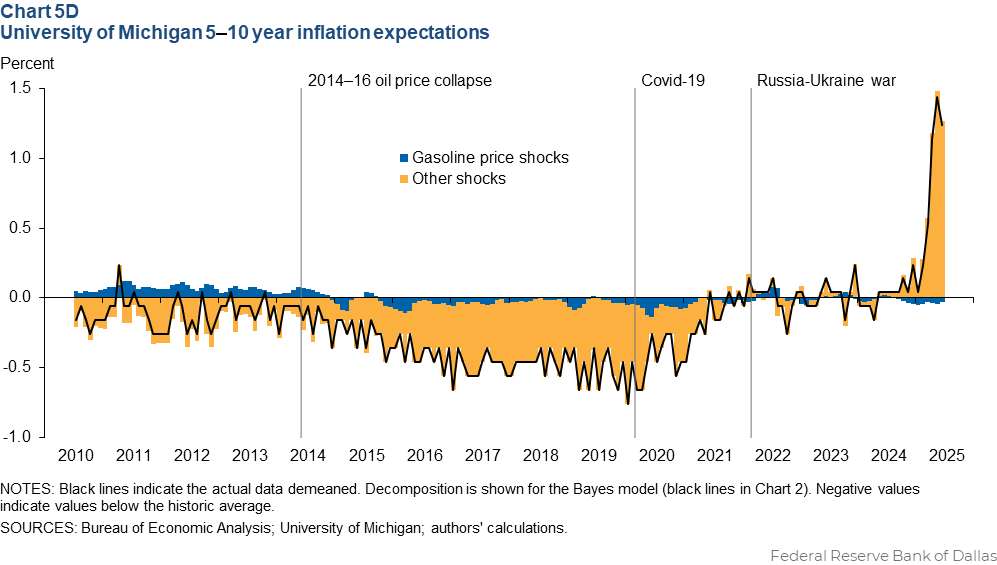

Together, these results show that gasoline price shocks do not persistently affect inflation or inflation expectations. Combining these responses with realized gasoline price shocks over time, Charts 5A–5D quantify the contribution of gasoline price shocks to inflation and inflation expectations since 2010. They show that gasoline price shocks were not major contributors to surging inflation or inflation expectations during 2021–24.

How inflation and inflation expectations respond

Turning to the oil price scenarios for June 2025 to December 2026, we first use our model to recover the sequence of gasoline price shocks implied by each of the three scenarios. (We assume the pass-through from oil to gasoline prices is 50 percent, reflecting the cost share of oil in gasoline prices). The model then quantifies the effects of these shocks on U.S. inflation and inflation expectations.

Table 1 shows the cumulative effects in December 2025 and June 2026 relative to the benchmark of no conflict between Israel and Iran implied by the preconflict oil market outlook in Chart 1. The Israel-Iran ceasefire holds scenario implies almost no effects beyond six months, because the shock is small and is largely reversed in subsequent months.

| PCE inflation | Core PCE inflation | |||

| Dec. ’25 | Jun. ’26 | Dec. ’25 | Jun. ’26 | |

| Israel-Iran ceasefire holds | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Resurgence of Middle East conflict | 0.74 | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.15 |

| Closure of the Strait of Hormuz | 1.28 | 0.80 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| University of Michigan 1Y | University of Michigan 5–10Y | |||

| Dec. ’25 | Jun. ’26 | Dec. ’25 | Jun. ’26 | |

| Israel-Iran ceasefire holds | -0.02 | -0.01 | -0.00 | 0.00 |

| Resurgence of Middle East conflict | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Closure of the Strait of Hormuz | 0.43 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| NOTES: Headline and core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation are expressed as cumulative effects in percentage points (annualized) relative to the benchmark of no Israel-Iran conflict. Inflation expectations are expressed as changes in percentage points relative to the benchmark of no-conflict at specific horizons. Estimates obtained using the Bayes estimate are shown as black lines in Chart 2. SOURCE: Authors’ calculations. |

||||

Under the severe scenario, the Strait of Hormuz closes, headline and core inflation rise in the months leading up to the closure. This results in a cumulative 1.3-percentage-point increase in the annualized headline inflation rate and a 0.3-percentage-point higher annualized core inflation rate in December 2025 relative to the benchmark of no Israel-Iran conflict. The inflationary effect diminishes when oil and gasoline prices stop rising. By June 2026, the cumulative effect on annualized headline inflation falls to 0.8 percentage points.

The effects on core PCE inflation and one-year inflation expectations are somewhat sluggish. In the severe scenario, for example, core inflation remains 0.3 percentage points above what it would have been absent the conflict in June 2026, and one-year inflation expectations remain 0.2 percentage points above.

What possible future outcomes could mean for policy

While hostilities between Iran and Israel ended quickly in June 2025 without a major oil supply disruption, it is worthwhile to explore the impact on inflation and inflation expectations if this geopolitical event had turned out differently.

One of the worst scenarios for oil trade would be a temporary closure of the Strait of Hormuz causing a substantial surge in the global oil price. Our analysis suggests that even under an extreme scenario such as this, the inflationary effects on the U.S. economy in the near future would be comparatively modest. Inflation expectations have remained anchored in recent years, and policymakers should, thus, be careful to avoid overreacting.

About the authors