Texas economy rides wave of changing technology and diffusion of know-how

When an economy expands, it typically adds workers, capital or both. Texas has grown more rapidly than other states and faster than the nation mostly because it keeps adding people and firms.

Another way to grow an economy is by increasing productivity. Innovation and technological advancement—how people do things—drive productivity growth and, with it, wages and the standard of living.

While Texas is known for its large size and relatively faster growth, its standing as a player in the knowledge economy may not be as readily recognized.

Major high-tech player

To many, the Texas story is one of oil magnates and real estate tycoons. But in recent decades, the state has emerged as an innovation and high-tech hub. Defense-related manufacturers turned to civilian applications after World War II, among them the predecessor to Dallas-based Texas Instruments. Electronic Data Systems, founded in 1962, was among the first firms in the U.S. to offer data processing services.

The state grew further during the 1990s internet bubble, when information technology and telecommunications firms flourished in Austin and Dallas. Today, Texas is home to numerous tech firms, including Dell and Oracle, with Austin and Dallas ranking among the most vibrant high-tech centers in the nation.

Assessing innovation

Innovation and technological development are challenging to measure, so researchers typically turn to patent- or employment-based metrics to gauge the intensity of such activities.

Patents grant exclusive rights to an inventor for a product or a process that provides a novel way of doing something. Thus, they represent the creation and dissemination of new knowledge. While patents do not capture all forms of innovation, they provide tangible evidence for a wide range of breakthrough activities.

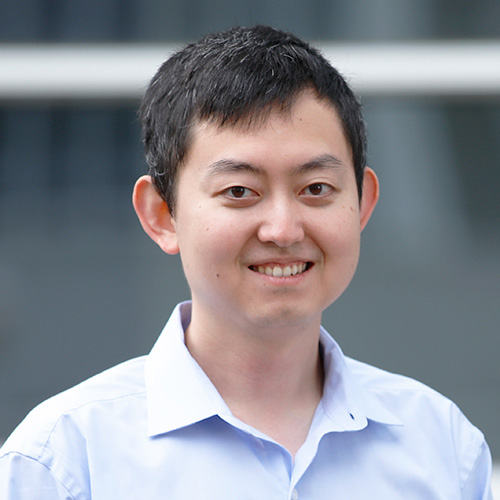

Texas-based inventors accounted for 7 percent of total U.S. patent applications from January 2018 to September 2020, according to U.S. Patent and Trademark Office data (Chart 1A). Based on the share of patent filings, Texas ranked second among U.S. states, though the gap between it and No. 1 California is wide.

California accounted for one-fourth of the U.S. total. Moreover, other large states such as Massachusetts and New York rank above Texas after accounting for population-size differences.

Employment-based measures

The concentration of high-tech employment within a geographic region provides a second measure of innovation. Research has established the benefits and significance of productivity spillovers from agglomeration—when similar or complementary firms and people locate near one another.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics defines high-tech industries as those with high concentrations of workers in STEM occupations—science, technology, engineering and mathematics—such as in software development, computer engineering and semiconductor manufacturing.[1]

Texas made up 9 percent of nationwide high-tech employment, slightly exceeding its overall share of U.S. employment. At the metro level, Dallas–Fort Worth (4 percent), Houston (2 percent) and Austin (2 percent) are major centers of high-tech employment (Chart 1B).

Most notably, innovation plays an outsized role in Austin as evidenced by the metro’s share of both patent filings and high-tech employment relative to its size. Austin makes up less than 1 percent of U.S. employment, but its share of the nationwide patent filings and high-tech employment is twice as large.

Role of disruptive technologies

A third measure of technological progress is adoption of disruptive technology—a groundbreaking innovation that either radically changes the way consumers or businesses work or creates a completely new industry. Examples include personal computers that replaced typewriters and transformed the workplace and email, which transformed written communication.

Research shows that even though disruptive technologies tend to be invented and initially used by firms concentrated in a few hot spots such as Silicon Valley, over time, these technologies slowly become available to companies elsewhere amid more widespread adoption.

Texas has been a major beneficiary of these highly disruptive technologies’ diffusion. Online job ads that include keywords such as “cloud computing,” “neural networks,” “antibody-drug conjugate” and “autonomous cars” are one way to measure the degree to which Texas companies adopt new technologies.[2]

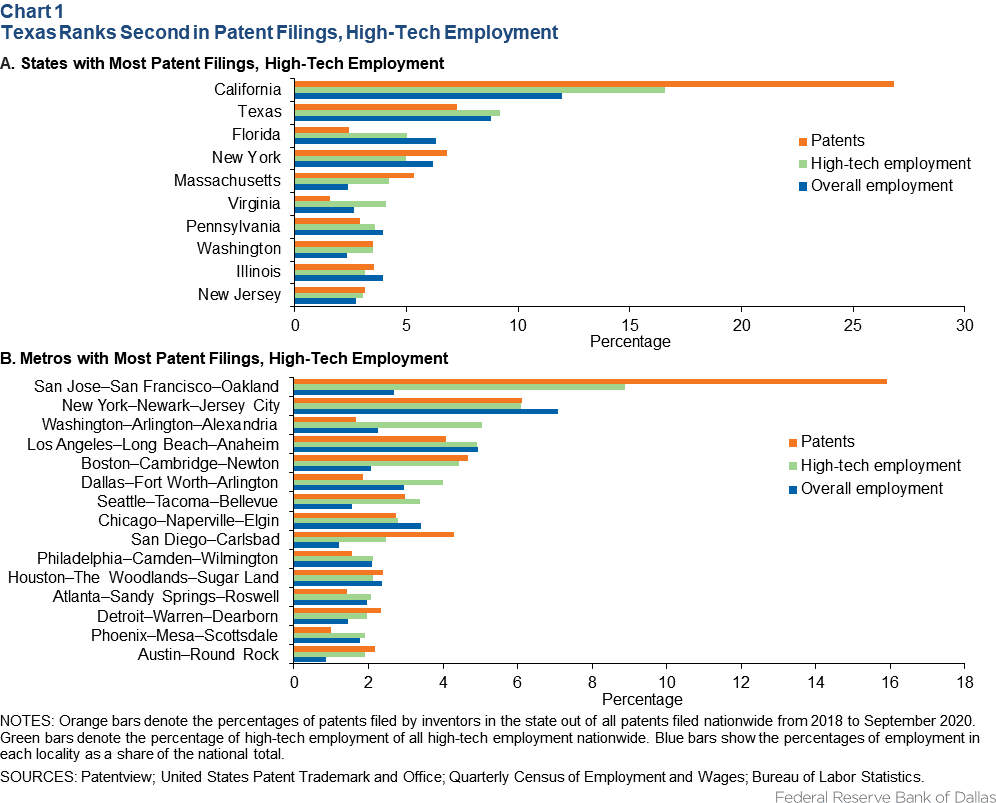

By this measure, Texas businesses tend to adopt cutting-edge technologies quickly, even if they are initiated elsewhere. Chart 2 shows the share of the nation’s jobs associated with the selected set of disruptive technologies (initiated around the 2010s decade) at the state and metro level. (For more information about job categories, see sidebar, "Leading Industries Accounting for High-Tech Employment.")

In 2012, a sizeable share of disruptive tech jobs nationwide was located in California (29 percent), particularly in the San Francisco Bay Area (13 percent). Over time, jobs requiring familiarity with or usage of these same technologies became more prevalent in Texas (Chart 2A).

As California’s share of these jobs dropped to 16 percent in 2022, the share in Texas doubled from 5 percent in 2012 to 10 percent in 2022. Among the major Texas metros, DFW benefited the most with its share of these job ads rising from 2 percent in 2012 to 4.5 percent in 2022 (Chart 2B).

Cloud-computing technology provides an example of such knowledge migration. In 2012, one-third of the jobs associated with cloud computing were concentrated in just two states—California and Washington—while only 7 percent were in Texas. By 2022, as the application of cloud computing vastly expanded, California’s and Washington’s share of jobs associated with cloud computing fell to 17 percent, while Texas’ share increased to 11 percent.

Such diffusion may be organic as companies in Silicon Valley and Seattle specialize in designing and marketing the cloud-computing infrastructure, while many telecommunication, professional and business services, and advanced manufacturing companies in Texas are major users of these technologies. Besides technological diffusion, the relocation and expansion to Texas of numerous high-tech firms such as Oracle, Google and Apple and the opening of new plants and factories in Texas account for some of the growth over the past decade. The state’s central location and proximity to Mexico, access to commuter and cargo transportation, relatively low costs of living and of doing business, and clustering have all helped make Texas an attractive place for high-tech firms.

Rising skill profile in Texas

With the Texas economy’s increasing ties to high-tech, how has the state’s workforce kept up with the rising demand for skilled workers? High-tech workers typically have advanced degrees in engineering, mathematics and other STEM fields.

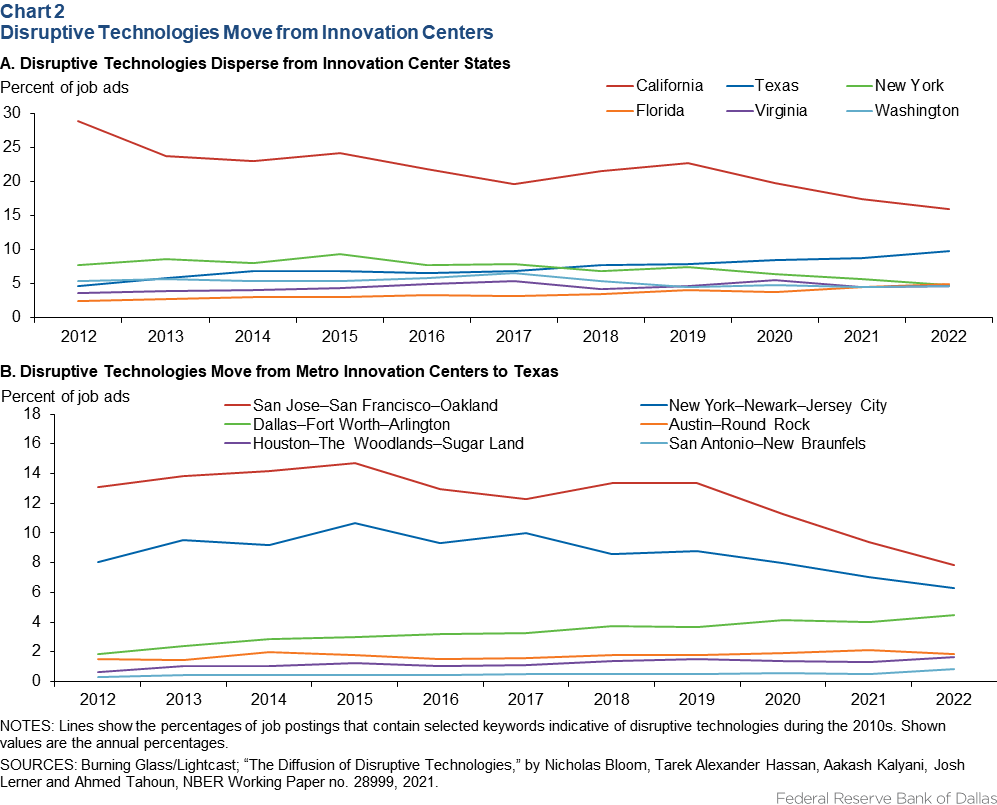

Texas’ skill profile has improved over the past decade, though the state still ranks among the bottom half based on the educational attainment of workers ages 25 through 65 (Chart 3). Texas ranked 30th among states in the share of such workers with a college degree in 2022, up from 37th in 2012.

The state’s ranking for workers with a master’s degree also climbed seven places from 2012 to 2022, but its position was unchanged at 40th for those with a doctorate degree. Despite the noteworthy progress, the educational skills gap between Texas and top-ranking states such as California, Massachusetts, New York and Washington remains significant, particularly for workers holding doctoral degrees.

Texas ‘brain gains’

The remarkable rise in Texas’ talent profile is driven partly by an increasing share of natives pursuing higher education but also from the migration of highly educated and trained workers to the state.

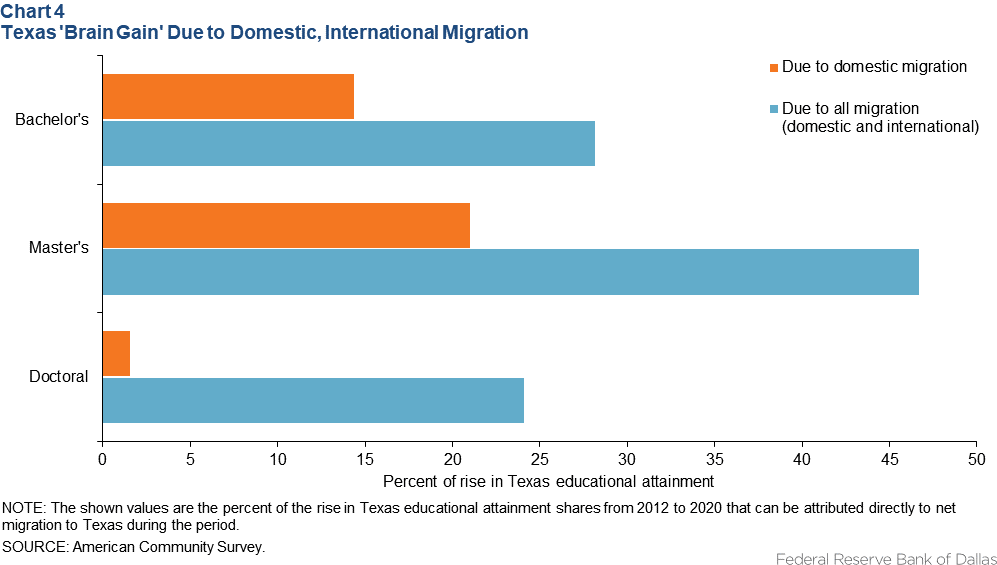

Currently, 37 percent of the Texas workforce ages 25 through 65 is college educated (a bachelor’s degree or higher), a significant improvement from 31 percent in 2012. A sizable portion (26 percent) of the 6-percentage-point rise can be attributed to becoming a “net importer” of talent (Chart 4).[3]

The share is even higher when looking at those with a master’s degree. Crucially, immigration to Texas significantly raised the skill profile of the state across all three education levels, particularly among those with advanced degrees. Recent Dallas Fed research shows that domestic and international migrants are filling critical workforce gaps for Texas.[4]

Expanding knowledge base

While Texas businesses have been quick to adopt disruptive technology and have made great strides in elevating the state’s educational profile and its concentration of high-tech talent, Texas has yet to catch up with the high-tech frontier states.

Nonetheless, the future is promising, assuming that the state continues attracting high-skill workers (including immigrants) and innovative firms. Together, they will further bolster Texas’ presence in the knowledge economy.

Notes

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics defines high-tech employment as the four-digit North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code industries that have a high proportion of scientists, engineers and technicians. We only use the high-tech level I industries to compute the shares of high-tech employment (see sidebar, "Leading Industries Accounting for High-Tech Employment").

- For more information see “The Diffusion of Disruptive Technologies,” by Nicholas Bloom, Tarek Alexander Hassan, Aakash Kalyani, Josh Lerner and Ahmed Tahoun, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper no. 28999, November 2021.

- The migration-driven rise in educational attainment is calculated by adding the annual net migration to Texas from 2012 to 2020 of the working-age population by education level to the observed Texas workforce in 2012. Since the American Community Survey does not include individuals who have moved abroad from the U.S., only U.S.-bound immigrants are included in the net migration calculation. Outbound emigrants are not included in the calculation.

- “Migration to Texas Fills Critical Gaps in Workforce, Human Capital,” by Diego Morales-Burnett, Pia Orrenius and Madeline Zavodny, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Dallas Fed Economics, Nov. 29, 2022.

Leading industries accounting for high-tech employmentThe Bureau of Labor Statistics defines high-tech employment as the four-digit North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code industries that have a high proportion of scientists, engineers and technicians. We only use the high-tech level I industries to compute the shares of high-tech employment. The industries included are: 3254: Pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing A job is associated with disruptive technologies if the skills requirements include any of the keywords below. These keywords reference disruptive technologies that arose in the 2010s and do not change over the duration of the analysis (2012–22). Keywords are: cloud computing, platform as a service (PaaS), cloud security application, cloud security architecture, cloud security data protection and privacy, cloud security infrastructure, cloud security planning, cloud security strategy, cloud security strategy and planning, cloud strategy, object recognition, image recognition, social networking, machine learning, neural networks, natural language processing, unsupervised learning and artificial intelligence. Also, mobile application design, mobile application programming, mobile applications, mobile platform development, search analytics, search engine optimization (SEO), search engine marketing (SEM), search marketing, video streaming, gaming industry knowledge, social gaming, solar energy, solar energy, hybrid vehicle, electric vehicle, radio frequency identification (RFID), computer vision, mobile banking, virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), unmanned vehicle systems, fuel cell, software defined data center (SDDC), antibody conjugations, therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, monoclonal antibody production, 3D printing/additive manufacturing (AM). |

About the authors

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2022/swe2204.