Migration to Texas Fills Critical Gaps in Workforce, Human Capital

People moving to Texas have historically helped fuel the state’s economic growth. While international migration to Texas has eased during the pandemic, domestic migration has filled the gap, sustaining the state’s expansion.

Those arriving tend to be younger and more educated than Texas’ overall population; those leaving the state are, too. Continuing to retain working-age Texans and attract new ones from around the country and abroad is vital to maintaining the state’s workforce—its human capital—as baby boomers retire and birth rates decline.

Populations grow in two ways: natural increase and migration. Texas’ rate of natural increase—births minus deaths—differs little from the U.S. rate. Migration provides Texas an edge because annual net migration—the number of people moving into the state minus those moving out—is typically large and positive.

Texas has experienced positive net in-migration for most of its history, and it’s the main reason the population grew from less than 21 million in 2000 to almost 30 million in 2021. About half of population growth during the past two decades is attributable to net migration into the state. Net domestic migration has averaged 108,000 people per year over the period and international migration about 83,000.

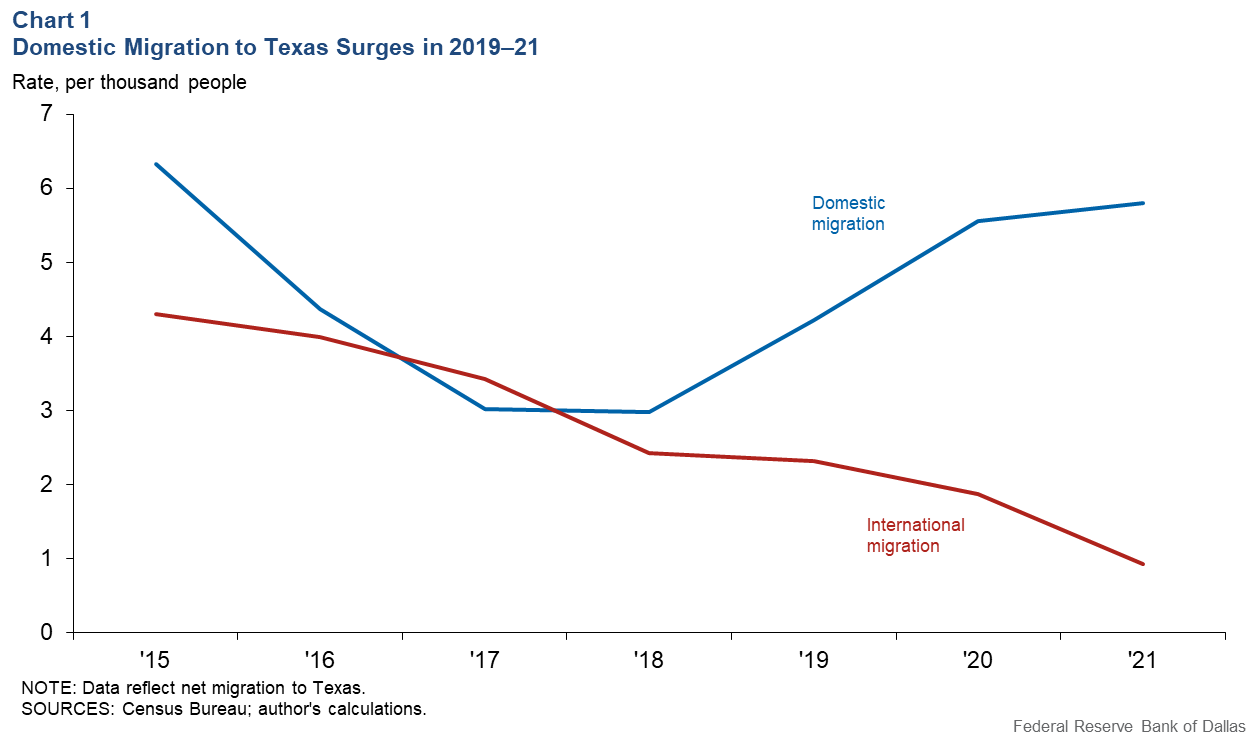

The domestic migration rate of 5.8 people per 1,000 residents in 2021 equaled 170,307 new arrivals from other states, about twice the population of Bryan, Texas (Chart 1).

Texas in-migration ebbs and flows with economy

Texas has experienced net out-migration a few times, as it did in the late 1980s when the oil bust and savings and loan crisis sent the state economy into a tailspin. Absent such sharp shocks, net inflows are usually positive and ebb and flow with the relative strength of the state economy.

Domestic net migration eases when economic growth in the rest of the U.S. closes in on the growth in Texas. For example, Texas net domestic migration grew during 2019–21 after being generally flat during 2015–18, according to Census Bureau estimates. The earlier period of 2015–16 included an energy downturn that slowed growth in the region relative to the nation.

Credit bureau data on address changes also indicate that net inflows continued to grow in 2021, with Texas second only to Florida among states gaining residents.

International net migration to Texas was slowing even before pandemic-related border closures in 2020. Overall, such changes in Texas largely mirror national trends. Net international migration to the U.S. peaked in 2016 and then fell sharply. There was little movement between the U.S. and foreign countries during the height of the pandemic. International inflows to Texas have since picked up, with strong labor markets acting as a magnet.

Perhaps as important as how many people come and go is who moves. Losing retirees to Florida or San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, while gaining young adults who are near the start of their careers packs a different economic punch than the converse.

New arrivals to Texas tend to be young

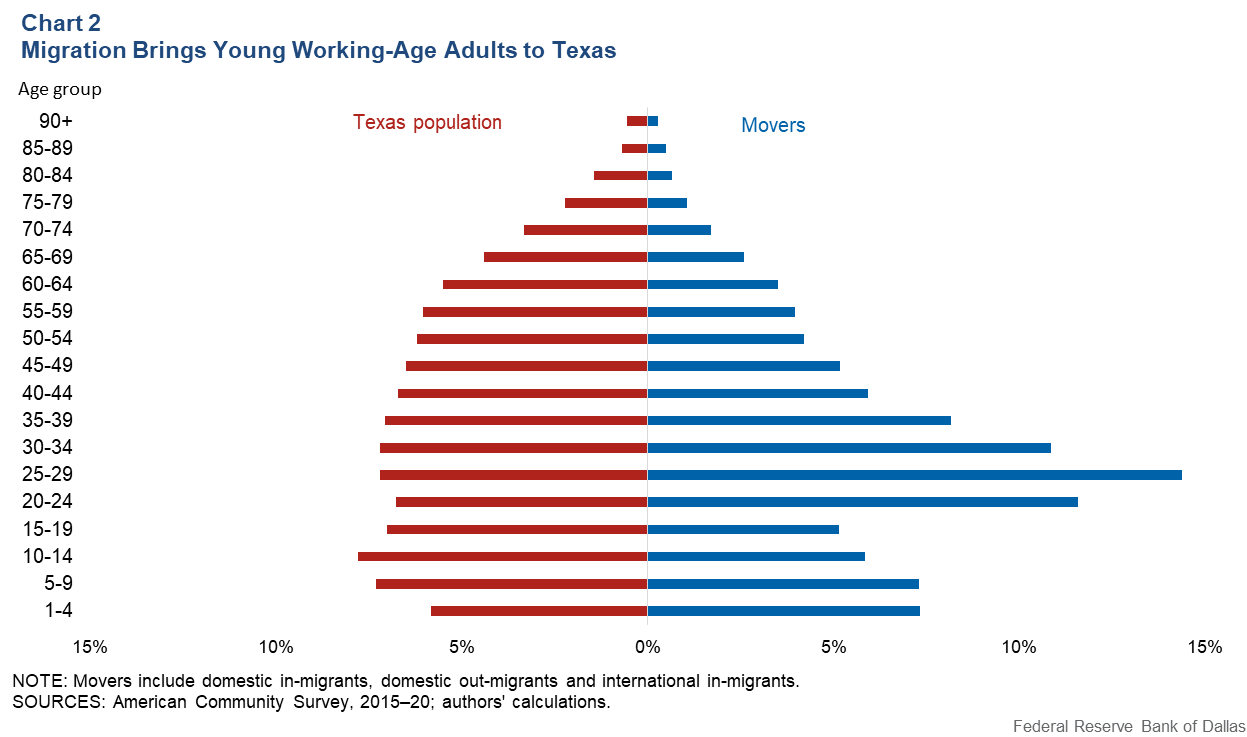

Movers—arriving and departing—are almost twice as likely as the Texas population to be ages 20 to 29 and are less likely to be younger than 20 or older than 39 (Chart 2).

There are few differences in the age distributions of in-migrants and out-migrants. While that may seem to suggest that young adults moving into Texas just offset those moving out, the state actually gains young adults on net since inflows are bigger than outflows.

Teens account for a surprisingly small share of movers, but the data do not include many college students because we exclude people living in group quarters, such as dormitories. In addition, parents of school-age children may be reluctant to move since it’s disruptive to schooling and relationships.

Migrants more likely to have college degree or greater

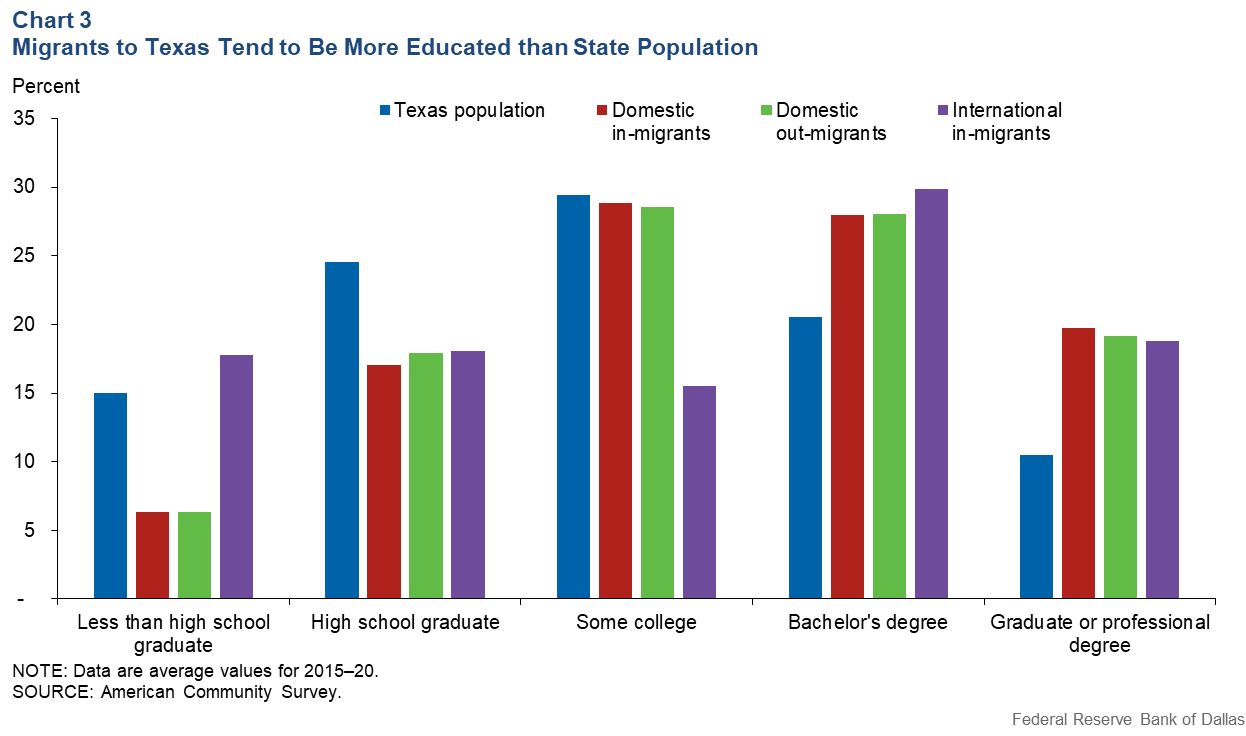

Relative to the Texas population, domestic in-migrants and out-migrants are far more educated, possess similar household income and individual earnings, and have a higher unemployment rate, American Community Survey data show (Chart 3). While only 32 percent of Texans have a four-year college degree or higher, nearly 50 percent of movers do.

Interestingly, the median annual wage and salary of domestic migrants, $32,779, is similar to that of the Texas population, $36,080, according to American Community Survey data. Despite the education gap between the two groups, migrants’ incomes are slightly lower, in part because migrants are younger and haven’t fully reached their earnings potential.

New international migrants’ median annual wage and salary of $23,233 is much lower, largely because of the mix of educational attainment within the group—while half have college degrees or higher, more than one-third don’t have formal education beyond high school.

The higher unemployment rate among movers suggests it can take a while for them to find a job if they don’t relocate to Texas with one already in hand. And the low labor force participation rate among international in-migrants is concentrated among Hispanic immigrant women, who may choose not to work because they are caring for young children, among other reasons.

Filling in-demand jobs where worker supply is short

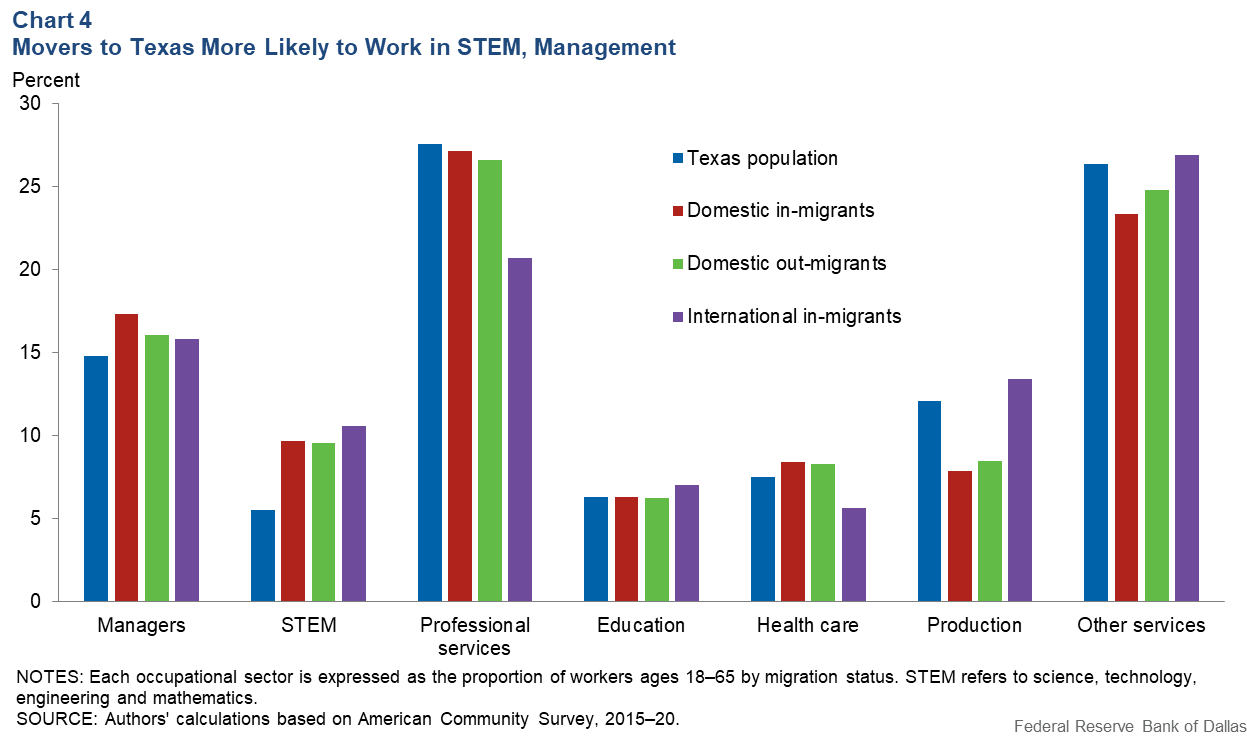

Employers may count on in-migrants to help fill jobs for which Texans are in relatively short supply, while out-migrants may move for better job opportunities. The distributions of Texans and migrants across occupation groups suggest some differences in the types of jobs they fill.

Migrants are much more likely than Texas workers as a whole to hold jobs in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) occupations (Chart 4). They are also more likely to be managers. If coming from elsewhere in the U.S., they are somewhat more likely to work in health care.

International in-migrants are overrepresented in management and STEM occupations, as well as in education, but are less likely to work in professional services and health care than the other groups.

Because many international in-migrants are either less-educated than the average Texan or have skills that don’t transfer readily to the U.S. labor market, they are more likely to work in occupations that require less formal schooling, such as production (manufacturing, extraction and construction) and other services (protective services, personal care and food preparation).

International migration increases racial, ethnic diversity in Texas

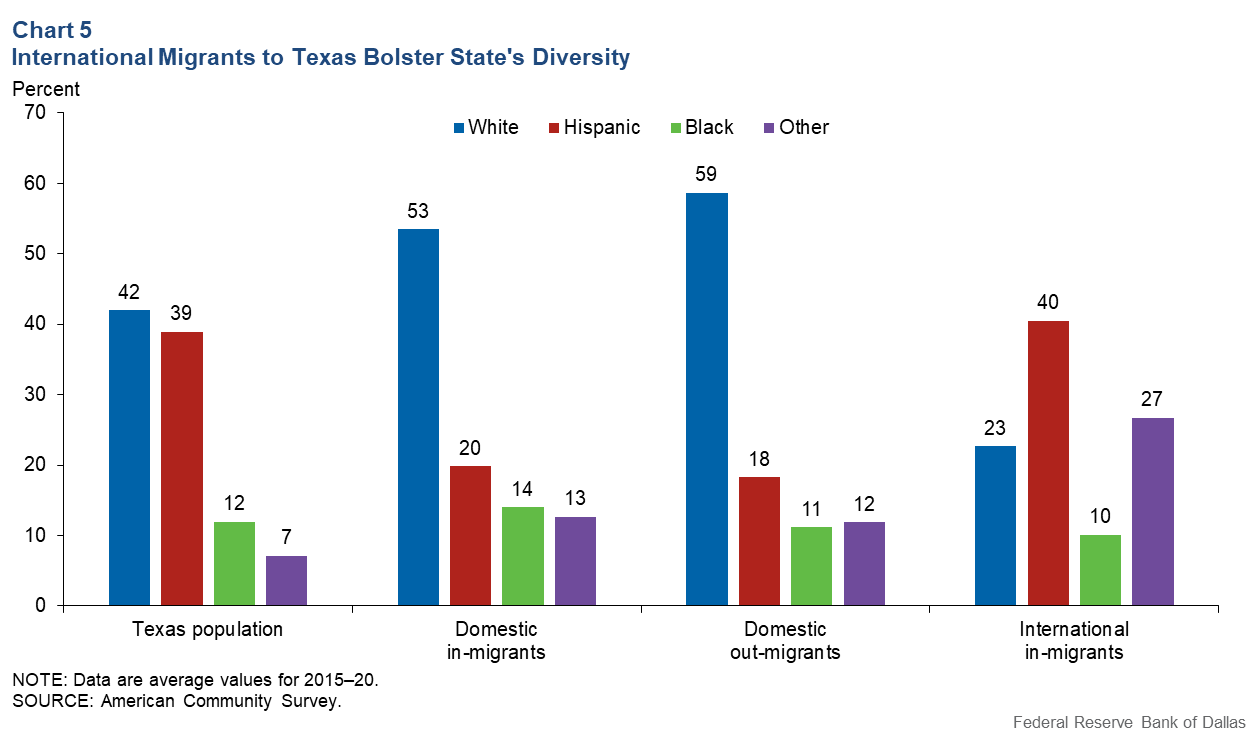

Hispanic and Black Texans make up more than half of the Texas population (Chart 5). Domestic migrants reflect the demographic make-up of the rest of the country, which remains majority white. International in-migrants are largely Hispanic and Asian, with the preponderance coming from Mexico, Central America, India and China.

State’s rapid employment growth largely attributable to migrants

Employment grows on average about twice as fast in Texas as in the nation. Consistent and sustained net in-migration from other states and abroad makes this possible.

Migrants differ in their attributes from each other and from native Texans, and this is also why they are so important. The state economy depends on these predominantly young people to contribute to growth, now and in the future, in a diverse set of industries and occupations.

What the state workforce lacks can largely be made up with domestic and international in-migrants as long as they are willing and able to come.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.