Strong peso, stubborn inflation cloud Mexico’s 2024 growth prospects

Despite nascent nearshoring trade expectations, the Mexican economy will be challenged by a welter of economic issues during the second half of 2024. The most notable are a still-restrictive interest-rate environment even as Banco de México has begun easing monetary policy, a strong peso and soaring labor costs. Potential economic softening in the U.S. further complicates the outlook.

Long-run challenges also remain, such as reversal of earlier energy sector reforms, poor productivity growth and high crime and violence.

However, Mexican government spending and the possibility of more fulsome nearshoring of manufacturing operations or suppliers could help the country consolidate its position as the main supplier to the U.S. market and aid prospects for 2024.

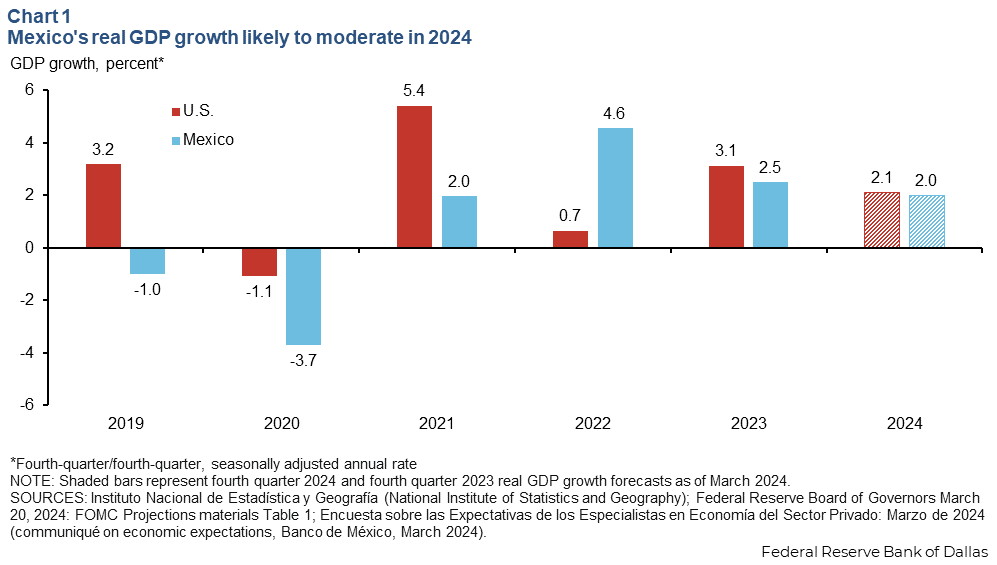

Real (inflation-adjusted) GDP growth is expected to moderate to 2.0 percent in 2024, down from 2.5 percent in 2023 (Chart 1). Domestic investment and consumption drove performance in 2023, with notable strength in the service sector, construction and auto production.

Government outlays support short-run growth

Mexico’s 2024 federal budget projects government spending rising to 26.4 percent of GDP from 25.6 percent of GDP in 2023 and from a 10-year average of 24.7 percent of GDP. Social programs remain a priority, representing about 50 percent of the total budget. The main federal social programs are pensions for the elderly, school rehabilitation and basic education scholarships, and reforestation and development of sustainable rural communities.

The government’s revenue estimate is conservative. Notably, oil sales assume a price of $57 per barrel compared with the early 2024 price of Mexican mix near $70 per barrel. If oil remains elevated, the government may seek to spend even more than originally planned. Either way, unusually high and growing government spending could fuel inflationary pressures.

Anticipating the impact of nearshoring

There is expectation that nearshoring could significantly benefit Mexico’s economy and deepen the U.S.–Mexico economic partnership. Nearshoring is the relocation of company operations and supply chains from overseas to North America, principally from China to Mexico.

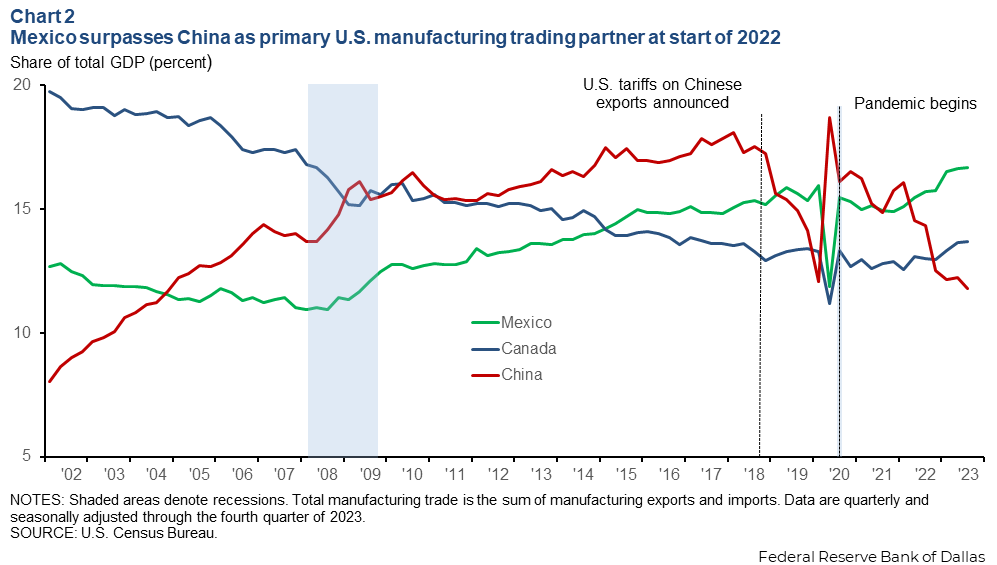

Higher U.S. tariffs on goods from China and U.S. industrial policy favoring North American production and inputs have helped reshape some global value chains in ways that may benefit Mexico.

Supply-chain dislocation during the pandemic has also lent urgency to the idea of derisking supply chains by bringing them closer to their ultimate destination, generally the U.S.

Mexico surpassed China as the main manufacturing trading partner of the U.S. in 2022 and was the principal trading partner in 2023 (Chart 2). If this trend continues, it will produce positive economic spillovers within Mexican manufacturing, expanding into the services sector and contributing to higher growth levels in 2024 and beyond.

Recent Georgetown University research shows that before 2022, nearshoring had increased Mexico GDP around 1 percent. The rise is in part attributable to higher exports of computer and peripheral equipment, semiconductors and other electronic components. Georgetown researchers estimate a 0.8 percent GDP increase in the succeeding years. When adding up the effects, nearshoring could bring an overall increase of almost 2 percent to Mexico’s GDP.

Mexican manufacturing shows signs of bulking up

There are also initial signs of nearshoring activity at the company level resulting from U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods that began in 2018. Firms that are part of the Mexican government’s Manufacturing, Maquila and Export Services Industry Program (IMMEX) and are part of global value chains have increased exports to the U.S. in skill and technology-intensive industries. They include chemicals, computers, aircraft and automotive. Overall, IMMEX firms are exporting more final goods.

Additionally, research by Mexico’s central bank found that after June 2020, manufacturing industries prone to relocating operations to Mexico from China, such as electric and electronic components, office equipment, and machinery and equipment, have exhibited higher levels of production and employment than other firms. Researchers pointed to signs the relocation process is slowly occurring in regions that traditionally receive greater flows of foreign direct investment, areas in the north and central parts of Mexico.

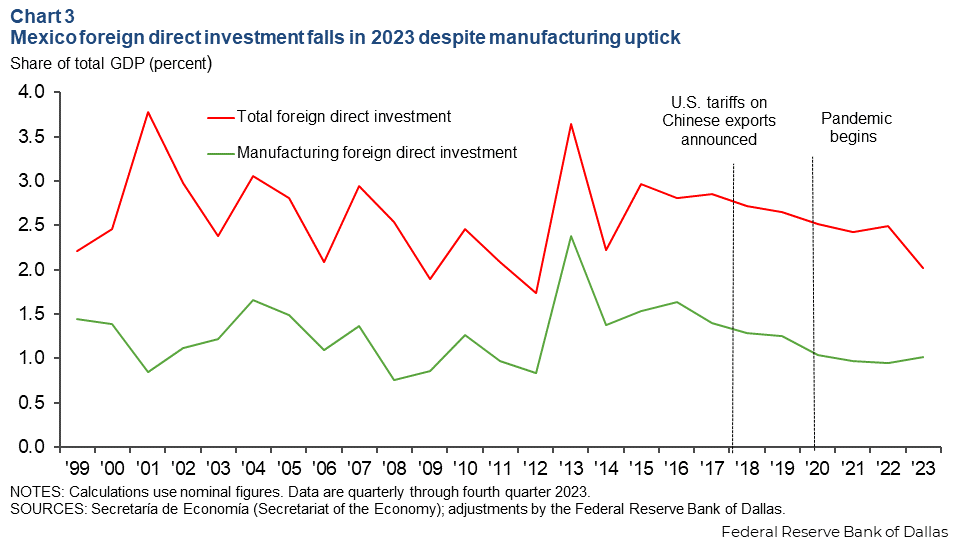

However, the expected increase in nearshoring-related foreign direct investment isn’t yet readily apparent. Foreign direct investment fell in 2023 despite slight gains in manufacturing, ending a slide that began in 2016 (Chart 3).

Reinvestment of profits in the same facilities accounted for much of the marginal manufacturing investment increase. Manufacturing companies are first expanding existing capacity, Dallas Fed contacts say, adding production lines, buying new equipment and adding employees. Companies are quick to announce new projects; however, it is unclear how many will be subsequently scaled back, delayed or canceled.

Elevated inflation among short-term challenges

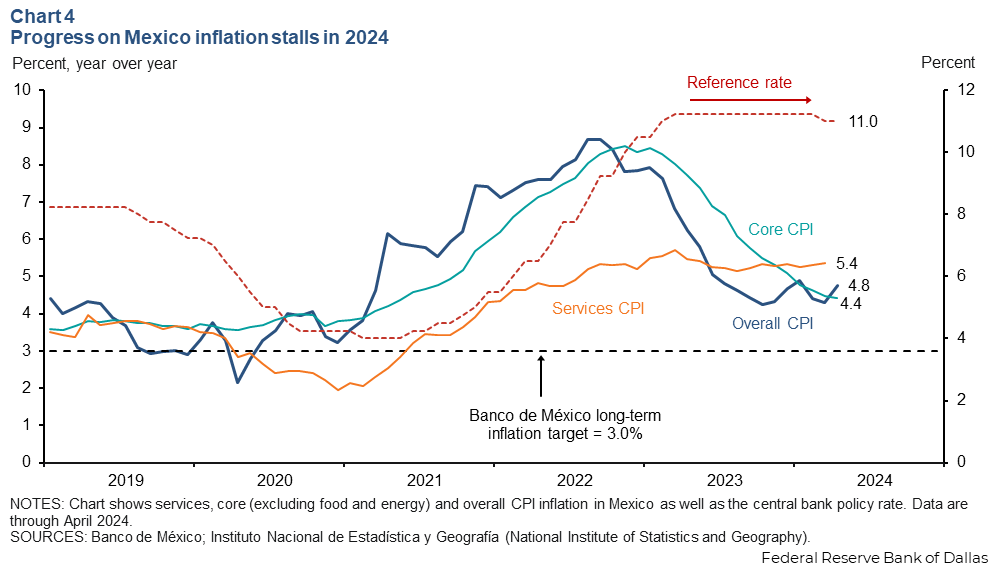

Less restrictive monetary policy should boost Mexico’s economic growth this year, although the impact may be muted, given policymakers’ cautious approach. Banco de México lowered its reference rate 25 basis points (0.25 percentage points) to 11 percent in March and held it in April, marking the end of the tightening cycle. The central bank had kept its policy rate unchanged for seven consecutive meetings, beginning in March 2023. The central bank is expected to favor a restrictive monetary policy stance due to persistent inflation concerns.

Inflation soared with the pandemic, reaching an annual rate of almost 9 percent, and the central bank’s proactive policy stance has helped reduce inflation. CPI core inflation, which excludes food and energy, has declined since early 2023. However, services inflation persists, keeping overall inflation above the central bank’s 3 percent target rate (Chart 4).

The central bank has indicated the reference rate will remain elevated, as inflation isn’t likely to converge with the target rate until the second quarter of 2025, signaling that the reference rate will remain high for some time. As a result, borrowing costs will stay elevated, damping investment and consumption this year.

High interest-rate differentials relative to the U.S. have also contributed to the peso appreciation. The Mexican peso has gained around 18 percent against the dollar in the past two years. A sustained appreciation of the peso boosts the relative cost of exports and reduces the cost of imports and could slow growth. The strong peso stymies tourism and foreign investment. Relocation of supply chains to include Mexico has offset some of the negative effects.

The strong peso also means dollar remittances are worth less to their recipients in Mexico. Despite record nominal remittances from Mexican citizens working in the U.S., the value of the payments has declined in real terms, which adjust for inflation and peso appreciation. While average dollar-denominated monthly remittances rose from $389 in 2022 to $393 in 2023, in real pesos they fell from 6,391 pesos to 5,398 pesos, a 16 percent drop.

Rising labor costs outrun productivity

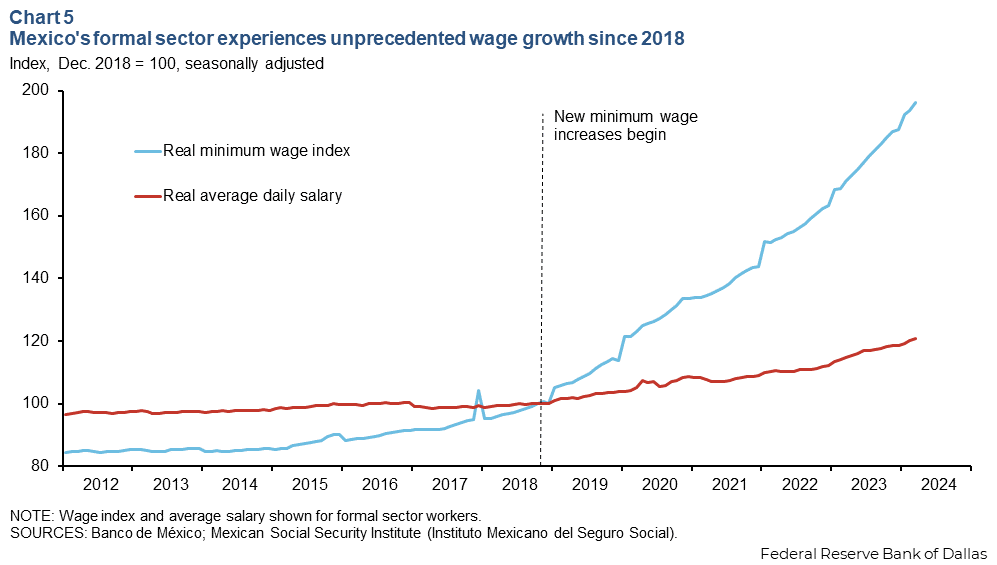

Labor costs are rising faster than labor productivity, posing another challenge. Mexico’s government has increased the federal minimum wage 88 percent in real terms over the past five years. The increases, at the start of each year, have been implemented annually.

Although the majority of workers in the formal sector—which the government can directly influence—earn more than minimum wage, it’s a reference wage that drives other labor costs and can push up prices (Chart 5). As a result, average daily wages in the formal sector increased 14 percent in real terms between 2019 and 2023.

Higher worker compensation is a benefit for workers and not a concern for firms and consumers if labor productivity gains match rising labor costs. But labor costs have increased faster than worker productivity in manufacturing and services since 2019. Unit labor costs increased 1.8 times faster than labor productivity in manufacturing and 1.5 times faster in services on a monthly, annual average basis.

When labor costs rise faster than labor productivity, they can impede hiring and lower the competitiveness of domestic and international firms in Mexico. The situation can also drive up hiring in the informal sector that is less compliant with minimum wage regulations.

Research by Mexico’s central bank finds a negative relationship between formal sector employment growth and federally mandated minimum wage increases. The study highlights the need to adopt measures that can increase labor productivity—the only way to sustainably create better-paying jobs.

Energy sector, fiscal discipline pose challenges to long-run growth

Mexico’s energy sector faces a number of barriers, particularly following the recent reversal of reforms enacted in the previous decade that had upended state-owned oil and electricity monopolies. Energy prices have risen amid lapses in reliability, particularly affecting manufacturing.

A lack of reliable and affordable electricity could damp nearshoring momentum. (Separately, Dallas Fed contacts have also noted the importance of providing access to plentiful and reliable water supplies.)

While fiscal spending boosts the economy, this year’s outsized expenditures represent a possible deviation from the fiscal prudence that characterized Mexican administrations since the 1990s. Some analysts see signals of structural change in fiscal discipline; others view the spending as temporary, no different than peer nations that didn’t experience any impact on country risk valuations.

The federal budget deficit this year is expected to be 5.4 percent of GDP, the largest since 1988. Much of it has been used to fund social spending programs and infrastructure projects.

There can be long-run benefits from fiscal spending, particularly if it represents investment in human capital and results in higher educational attainment and better health. Well-conceived infrastructure projects can also boost productivity and economic growth.

Conversely, a recent Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Southwest Economy report documents Mexico’s long history of disappointing productivity growth. The article notes that with labor force growth slowing, the nation must invest more in education and advanced technology in order to sustain future economic growth.

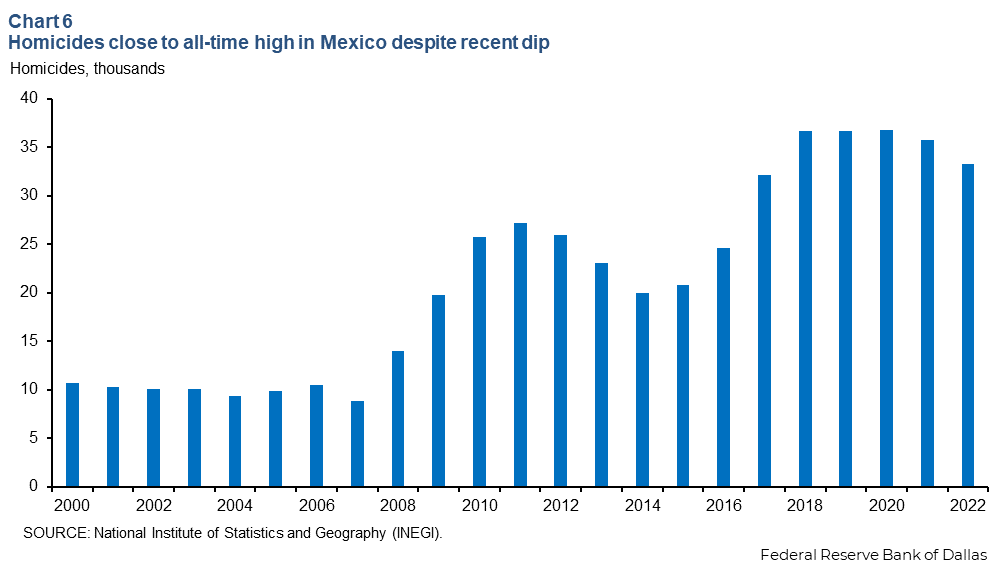

Crime, violence deter economic growth

High levels of violence and, more generally, criminal activity are obstacles to economic activity and foreign and domestic investment and ultimately long-run growth. Homicides have averaged 35,500 per year over the past four years, an increase of 25 percent from the previous four years (Chart 6).

Mexico’s homicide rate of 28 per 100,000 population compares with the global average of 6 per 100,000, the U.S. at 7 per 100,000 and Latin America and the Caribbean at 20 per 100,000.

Homicide is correlated with other activities, such as corruption and extortion and compromised law enforcement, which harm commercial growth and entrepreneurship. Crime disproportionately constrains micro and small firms in Mexico, prompting them to defer growth plans and reduce working schedules or even close. Crime raises operating costs, notably for security personnel and transportation. In addition, research shows that homicides and thefts negatively affect foreign direct investment.

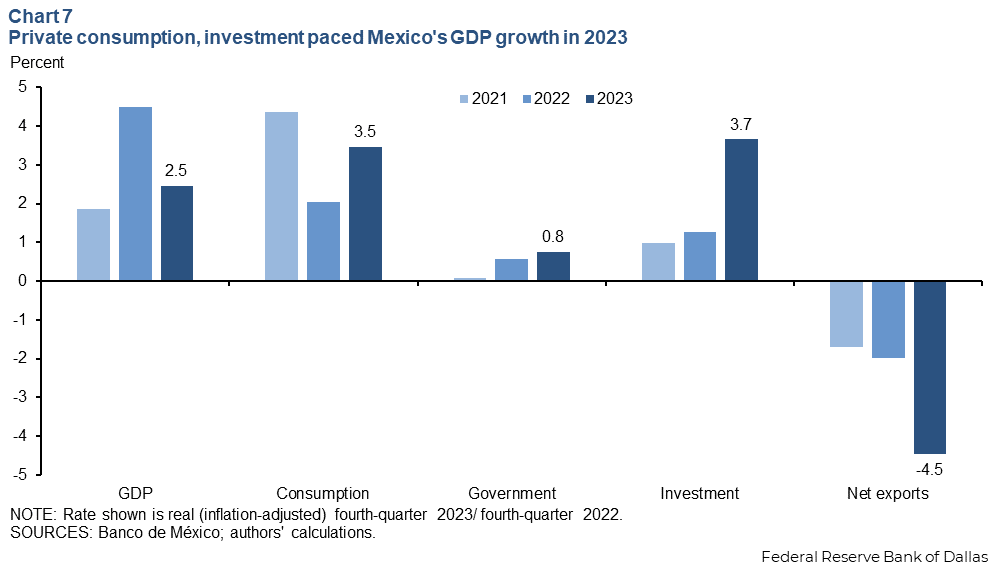

Domestic investment, consumption momentum pace growth

Strong private domestic investment and consumption accounted for the bulk of GDP growth in 2023, offsetting the weak external sector performance (Chart 7).

Private investment has trended higher as the pandemic recedes. The increase in private investment is partly due to investment catching up with suspended pandemic-era projects. Companies have taken advantage of the peso’s buying power to replace outdated machinery and equipment. Finally, some of this domestic private investment is in preparation for nearshoring projects, according to anecdotal evidence.

Private consumption has also grown steadily since the pandemic, fueled by a strong labor market and unprecedented real wage growth as well as record high remittances from the U.S.

Strong labor market conditions in the U.S., wage growth and unprecedented pandemic-era fiscal stimulus explain the flow of real remittances from the U.S. At the micro level, remittances generally go to families in Mexico’s poorest states in the central and the southwest regions. There, the payments smooth consumption and are mainly used for necessities such as food, clothing and health care.

Public investment is also growing after years of decline, notably major construction projects such as the Maya train in the Yucatan Peninsula and the Dos Bocas refinery in Tabasco. Still, the government’s contribution to GDP growth is relatively small.

Net exports were a negative contributor to real GDP growth in 2023, as bilateral surpluses with the U.S. and Canada were more than offset by deficits with Asia and Europe. China alone accounted for more than half of the deficit with Asia. The strong peso and falling oil exports also contributed to the negative balance.

Slowing growth anticipated through year-end 2024

The Mexican economy is expected to continue slowing in 2024, with only moderate expansion in the U.S. dimming prospects. A beneficial slowing of inflation in Mexico may follow.

It is unclear if domestic investment, particularly construction investment, a major contributor to economic growth last year, can continue this year as major infrastructure projects are close to completion. Presidential elections in the U.S. and Mexico will likely add to uncertainty about future prospects.

Remittances may have topped out, and U.S. economic slowing could diminish manufacturing exports. Indications of nearshoring acceleration are scant. Were it to materialize, such activity would provide growth potential in 2024 and in coming years.