Pandemic disproportionately affects women, minority labor force participation

COVID-19 has created unprecedented disruption in the U.S. labor market. Not only did it propel the unemployment rate in April to the highest monthly rate on record, but it has also greatly affected labor force participation rates—the number of people either employed or unemployed as a proportion of the population.

The participation rate declined from 63.4 percent in February to 60.2 percent in April—the first two months of the pandemic—when many businesses closed as workers and customers stayed home to avoid the virus. Since then, the participation rate has increased but remains 1.7 percentage points lower than in February.

Even more concerning, these trends show up in the prime-age (ages 25–54) participation rate, which is less affected by aging demographics than the total participation rate. Since February, the prime-age participation rate has fallen by 1.8 percentage points.

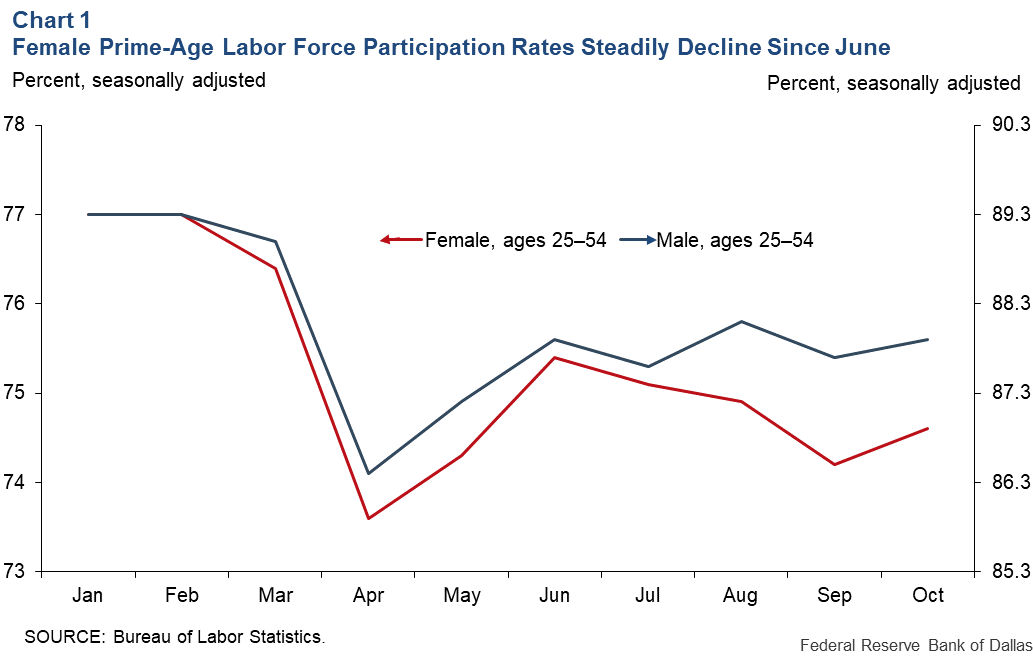

The male and female participation rates moved together from March to July (Chart 1). However, in August and September, female participation declined by roughly a percentage point, while male participation ticked up slightly. The timing of this gap suggests that remote learning and increased child care responsibilities are important factors in the decline in female participation. In October, participation rates ticked up for both men and women, but remained 0.8 percentage points below June levels for women and flat relative to June for men.

Changes in labor force participation rates for several demographics reveal that women with children, especially Black women, have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic, figures through September show. Microdata used to document participation rates for these groups isn’t available for October; thus, our granular analysis is complete for the first three quarters of 2020.

Women more prone to leave pandemic-era labor force

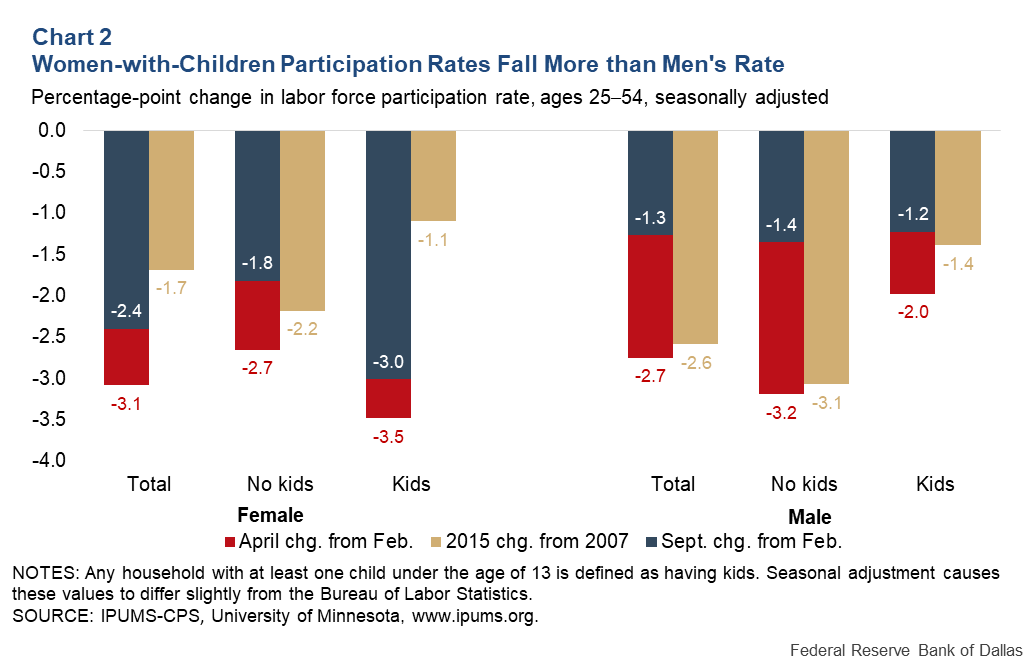

The pandemic has affected prime-age men and women differently (Chart 2). The female participation rate declined by 3.1 percentage points between February and April. Since April, it has regained 0.7 percentage points, or 22 percent of the initial decline, ending 2.4 percentage points below the February level.

Similarly, the male participation rate fell 2.7 percentage points in the first two months of the pandemic. It has since regained 1.5 percentage points of the initial decline and is down only 1.3 percentage points.

This experience is the opposite of what happened in the aftermath of the Great Recession, when the male participation rate declined far more than the female participation rate from 2007 to 2015.

Presence of children in the home alters labor behavior

Separating men and women based on whether they have at least one child under the age of 13 living with them suggests one important driver of the differences in labor force participation: an unequally shared burden arising from an increase in child care responsibilities.

The percentage-point changes in February-to-September male participation rates are essentially identical regardless of the presence of children at home (no kids: -1.4; kids: -1.2). In contrast, the participation rate for women with kids has declined a full percentage point more than it has for women without kids (no kids: -1.8; kids: -3.0), likely because many mothers are unable to work while they oversee remote learning and lack child care.

The differential effect of the pandemic on mothers is robust across demographic groups, but certain segments of the population have experienced a particularly large decline in labor force participation.

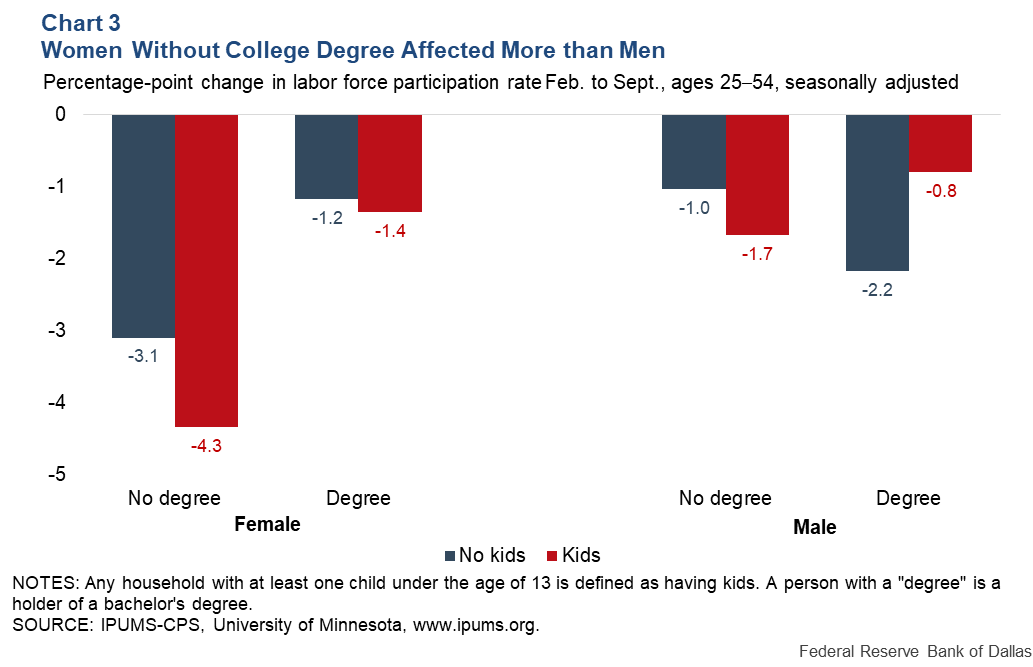

Chart 3 breaks down the February-to-September change in male and female participation rates based on whether an individual has a bachelor’s degree. Consistent with the aggregate results, the participation rate for women without a bachelor’s degree declined more if they had young children (no kids: -3.1; kids -4.3).

For those with a bachelor’s degree, the decline in the participation rate was considerably smaller, and the declines were nearly identical regardless of whether they had young children (no kids: -1.2; kids -1.4). This likely reflects the higher share of college-educated women in professions who can work from home.

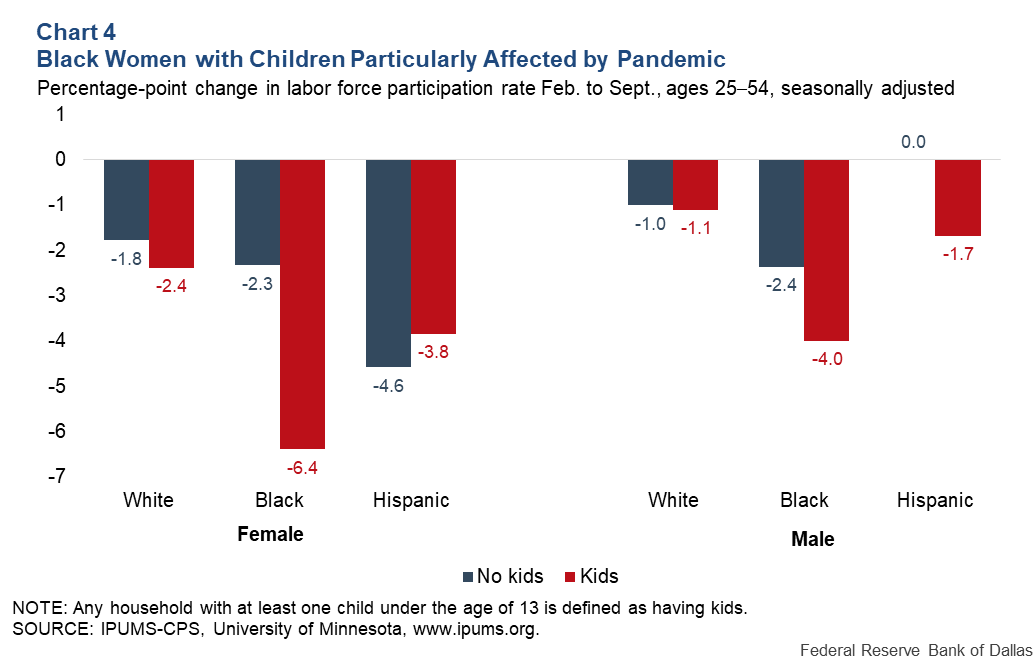

Chart 4 examines the differences between men and women by race and ethnicity. One result stands out: The February-to-September decline in the participation rate among Black men and women with kids is larger than for any other demographic group.

Among Blacks, the male participation rate fell 4.0 percentage points, while the female participation rate dropped 6.4 percentage points. For Black women, this is a much larger decline than in the Great Recession and a 1.2-percentage-point decrease from April to September. The participation rate among every other demographic group has improved since April.

The 4.1-percentage-point participation rate decline for Black women with children relative to Black women without children is far more negative than for any other group. This suggests that Black women’s labor market prospects are being disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and resulting lack of child care.

This is particularly disheartening, as this group had some of the largest employment gains from 2015 to 2019, when the strong labor market pulled in new or previously discouraged workers.

Long, slow recovery for women with child care responsibilities

Prime-age labor force participation rates as of September are uniformly lower than they were in February, following the sharp decline in March and April as the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in the U.S.

Women with children, particularly Black women and those without a bachelor’s degree, faced the sharpest declines and have recovered at much slower rates relative to those without kids.

One might conclude that these developments are unique to the pandemic and will return to their pre-pandemic levels. However, the slow recovery from the Great Recession tells us that declines in participation rates, particularly for vulnerable demographic groups, can take years to fully recover, and they hinder overall economic growth.

Note

The time series underlying this analysis—the updated employment data by parental status—from IPUMS-CPS is shown through February 2021.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.