Fed liquidity facility successfully anchored commercial real estate amid pandemic

The value of commercial real estate—particularly office towers, retail centers and hotels—suddenly became uncertain when COVID-19 arrived in the U.S. in late February 2020.

One part of the Federal Reserve’s response to ensure continuation of the flow of credit to households and businesses was to reestablish the central bank’s Term Asset-Backed Loan Facility (TALF). Originally deployed in 2008 as a financial backstop amid the Global Financial Crisis, the facility helps support the issuance of asset-backed securities by anchoring prices for the most highly rated bonds.

We examine TALF use by investors in commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) during the pandemic and find that it played a key role supporting commercial real estate finance.

CMBS an important source of commercial real estate fnance

Federal Reserve data indicate that almost $3 trillion of commercial mortgages were outstanding at year-end 2019 (excluding those financing multifamily properties). The primary sources of capital were depository institutions such as banks ($1.8 trillion), life insurance companies ($401 billion), CMBS ($357 billion) and real estate investment trusts ($183 billion). Thus, CMBS accounted for about 12 percent of all commercial mortgages outstanding.

CMBS are bonds created through the process of securitization, with principal and interest payments derived from the underlying commercial mortgages. Securitization generally involves a process called tranching—allocating bond payments in a prescribed order across investors—with the most senior investors bearing the least at risk, receiving principal first and incurring any losses last. The senior bonds, which form the bulk of the securitization liabilities, are typically designed to achieve the top AAA ratings to reduce interest costs.

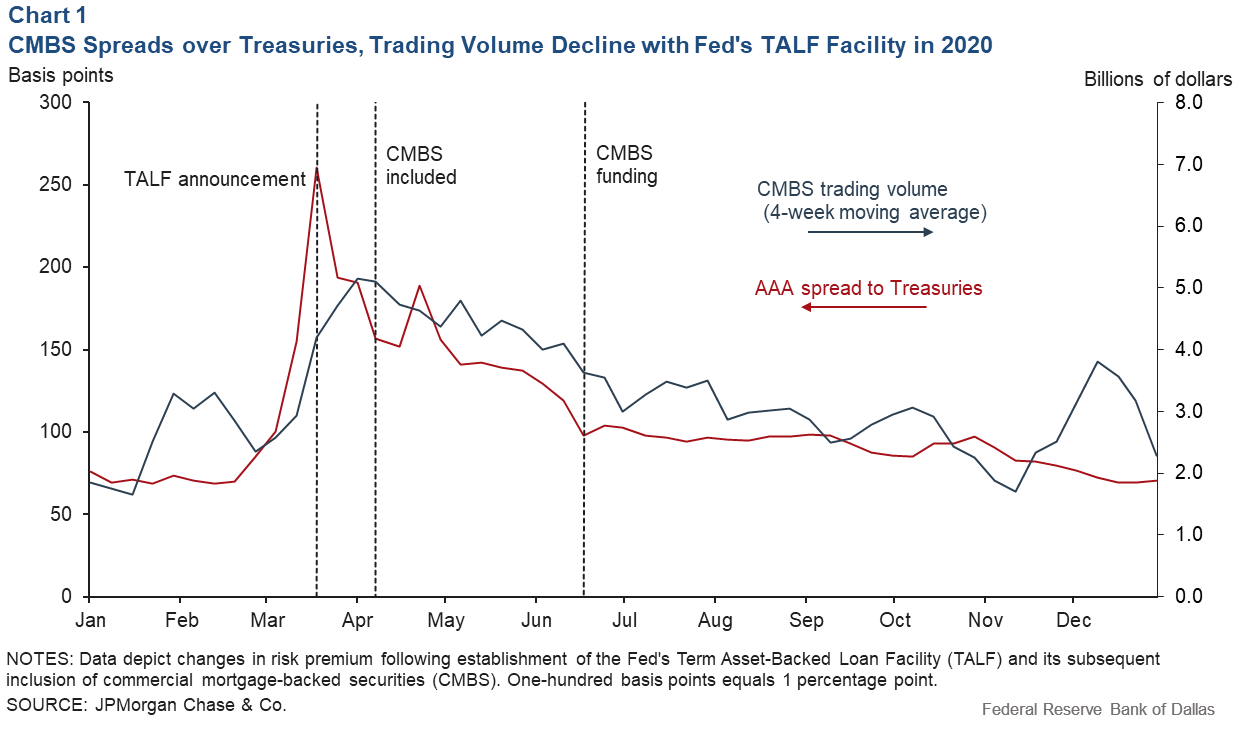

With the onset of the pandemic, trading activity in CMBS rapidly increased and yield spreads over benchmark Treasuries markedly widened in March 2020, which reduced the value of the bonds. (When a bond appears riskier, its market price declines as the interest rate demanded rises.)

Chart 1 illustrates these dynamics for 2020 using weekly data provided by JPMorgan Chase & Co. The chart highlights the dates of Federal Reserve announcements of the TALF program (March 23), the acceptance of CMBS as eligible collateral (April 9) and the first funded TALF loan for CMBS (June 25).

CMBS spreads widened from roughly 70 to 250 basis points in early March. Following the announcement of TALF and other liquidity facilities, spreads steadily declined, returning to their prepandemic levels by year-end.

TALF quickly deployed, backs CMBS in 2020

The TALF was an important part of the Federal Reserve’s response to the economic upheaval accompanying pandemic’s onset. It was one of several special lending facilities and provided collateralized, nonrecourse loans to investors holding AAA rated asset-backed securities.

TALF financing was available for a broad range of collateral types, subject to limits on the underlying instrument’s remaining term and leverage. Loans were for three years, were freely prepayable and were priced at a spread to risk-free rates. The spread was set at a level below pricing available in the then-stressed marketplace but above prepandemic pricing. This feature provided an incentive for investors to prepay TALF loans once stressed market conditions normalized. A recent Federal Reserve working paper explores the TALF in depth.

The Federal Reserve added outstanding CMBS as eligible collateral for lending through the TALF on April 9, 2020, and financed its first securities on June 25. For a CMBS with an average life of five years, pricing was set at 125 basis points (1.25 percentage point) above the three-year risk-free rate (based on overnight index swaps) and could finance up to 85 percent of the security value (a 15 percent “haircut”).

TALF financing for CMBS was unique because while existing (legacy) securities were eligible, newly issued ones were not. This decision reflected an expectation of little near-term issuance given the significant uncertainty around commercial real estate values.

TALF financing of legacy CMBS would ultimately support new issues by facilitating trading and price discovery and, thus, reducing liquidity premiums that emerged with the pandemic’s economic stress.

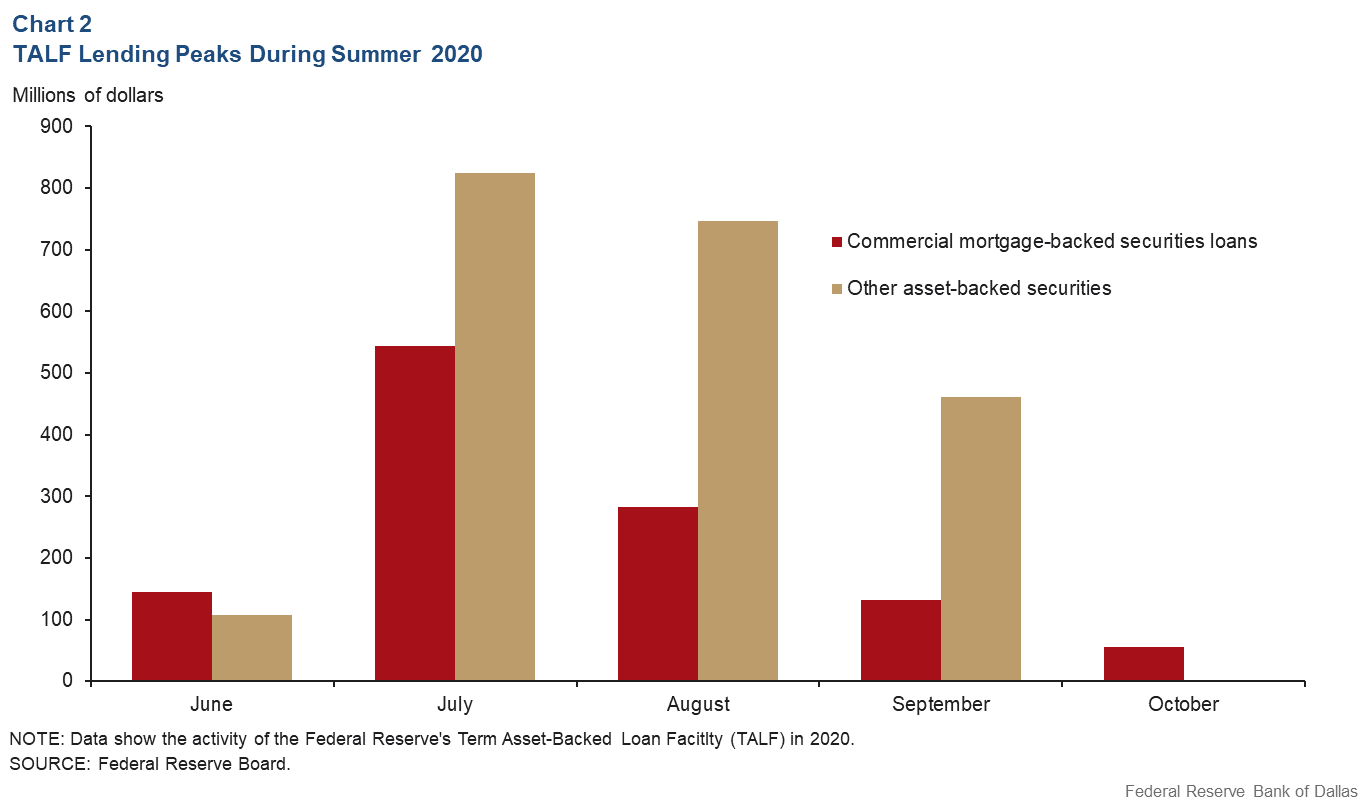

Chart 2 presents the monthly funding of TALF loans during 2020 for CMBS versus all other types of eligible collateral, such as auto loans and credit card receivables. During this time, 257 TALF loans totaling $4.5 billion were made, and CMBS was the most heavily financed asset class (112 loans totaling $1.2 billion). Virtually all TALF lending occurred between July and September 2020.

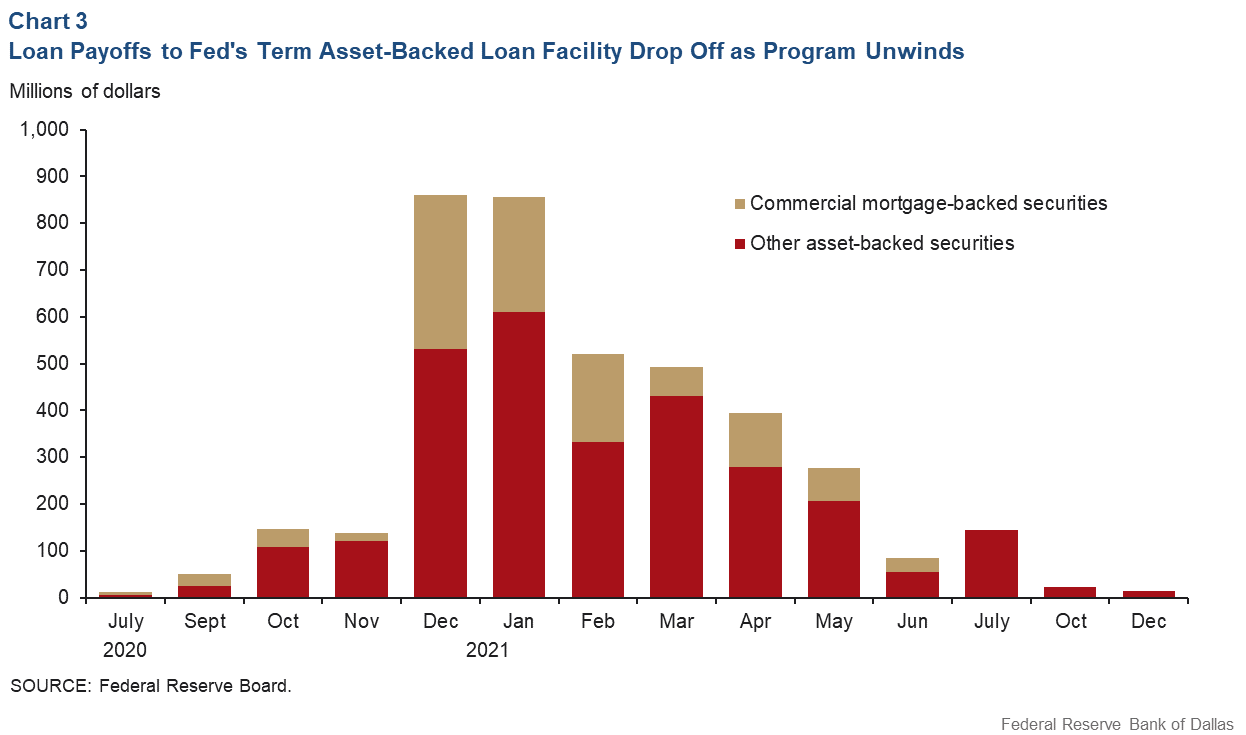

Payoffs of TALF loans began before the closing of the facility on Dec. 31, 2020 (Chart 3). This is consistent with spreads returning to pre-COVID levels by year-end 2020. Only 36 TALF loans remained outstanding as of January 2022, three of them backing CMBS (totaling $24 million). The rapid take-up and take-down of the TALF program suggests the facility worked as intended by providing a pricing floor.

Fed credit facility proved helpful in face of economic disruption

The Federal Reserve responded to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic with several liquidity facilities to ensure a continuing flow of credit to households and businesses. The TALF, which financed highly rated asset-backed securities, proved especially important in supporting commercial real estate finance.

The TALF program structure provided needed liquidity to investors at the height of the pandemic, but it incentivized borrowers to exit as normal market conditions returned, allowing the program to quickly unwind.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.