Eleventh District banks rely on core business, stay profitable as loan growth softens

Higher interest rates have discouraged new borrowing. Many banks have struggled to transition their loan portfolios to higher-earning assets. In industry parlance, loans typically constitute a bank’s primary assets. Meanwhile, a volatile yield curve, reflecting the difference between short-term and long-term rates, has strained banks still carrying substantial unrealized losses in their bond holdings. As interest rates rise, prices of existing bonds fall.

Despite this, credit has remained broadly strong as borrowers keep making payments and economic growth pushes ahead.

Yield curve normalization aids banks

The yield curve has emerged from an inverted or downward slope to a traditional upward slope, which depicts a situation more profitable for investors to borrow for a shorter term and lend for a longer term. This more typical upward curve tends to support most banks’ core business models.

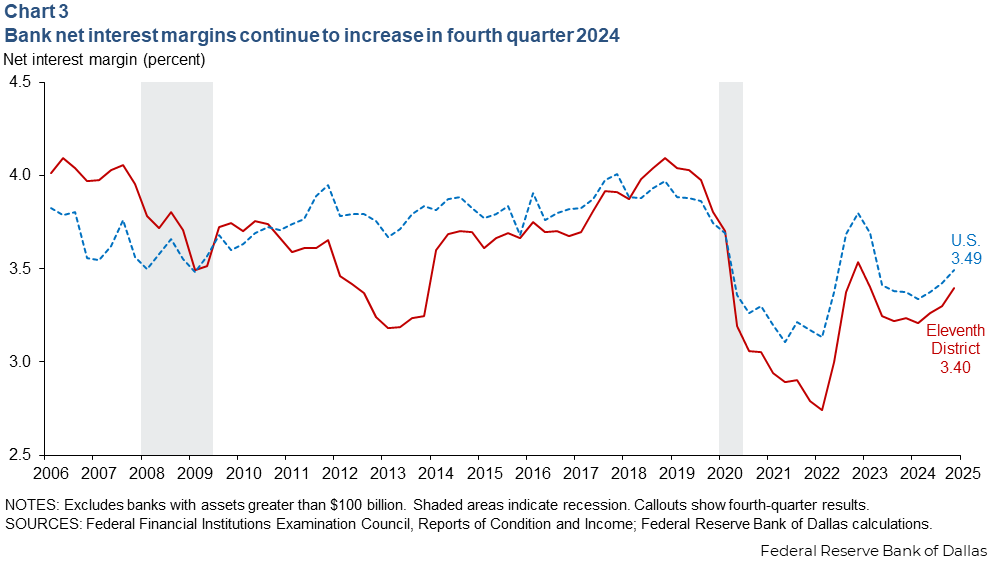

The return to a traditional yield curve has contributed to banks’ net interest margins recovering to 3.40 percent by year-end 2024, from 3.24 percent at the end of 2023.

From July 2023 to September 2024, the central bank’s two main short-term policy rates were at relative highs. The federal funds rate stood at 5.33 percent and the prime rate at 8.50 percent. The Fed subsequently undertook three consecutive cuts that lowered fed funds to 4.33 percent and the prime to 7.50 percent by December. (The fed funds rate is essentially the overnight borrowing rate banks charge one another for funds held at the central bank; the prime rate is the benchmark banks use to set customer loans.)

In contrast, long-term interest rates fluctuated substantially through 2024. The 10-year Treasury rate was 3.88 percent on Dec. 29, 2023, rising to 4.67 percent by mid-April 2024, before dipping to 3.66 percent in early September. It closed 2024 at 4.60 percent.

The Fed took steps to support the banking system following the failure of Silicon Valley Bank in March 2023. Within days, the central bank’s Bank Term Funding Program began seeking to stabilize bank liquidity. The Fed effort had substantial bank participation, peaking at $167.6 billion in lending before it stopped new activity a year later. The last of the program’s loans was repaid in March 2025, and banks have replaced that funding with new sources on terms that may be less favorable.

Banks do not appear to be turning to other short-term solutions such as borrowing from Federal Reserve banks’ discount windows or from Federal Home Loan Banks (originally envisioned to support housing-related lending). Commercial banks have, instead, successfully attracted enough deposits, including certificates of deposit and interest-bearing deposits at market rates, to replace deposits they lost in late 2022 and early 2023.

Looking ahead to the second half of 2025, a host of economic and administrative policies may affect banks in unpredictable ways across the Eleventh District, comprised of Texas, northern Louisiana and southern New Mexico. Return-to-office policies may revive prospects for commercial real estate loans to office buildings in central business districts, while broad-based tariffs may affect the outlook for loans to newly constructed warehouse and industrial facilities meant to support international trade.

An expansive energy policy focused on supporting fossil fuel production could support growth in the region despite lower oil prices, while newly initiated renewable energy projects may face a challenging environment. Interest rate cuts thought possible at the start of the year may not materialize in 2025 if elevated inflation persists.

Should economic growth slow in response to higher tariffs, a sharp decline in immigration and uncertainty around government spending, the Federal Reserve may face difficult choices in satisfying the dual mandate of full employment and price stability. Despite this backdrop of uncertainty, banks in the region benefit from a strong and vibrant Texas economy, with steady job growth so far in 2025.

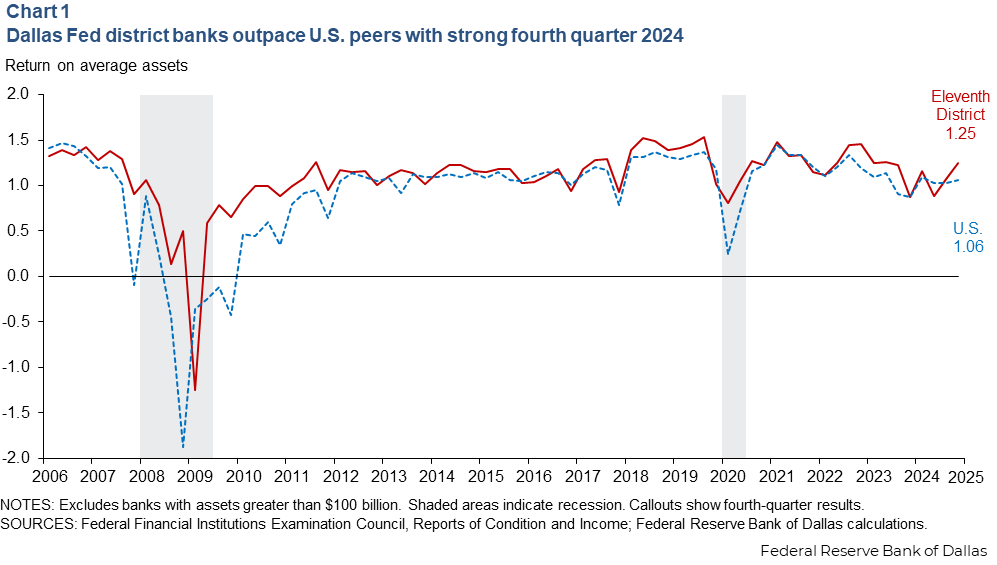

Banks maintain steady profitability

Eleventh District banks had a harder time putting assets to work in 2024 than in the prior year, with return on average assets dropping 5 basis points from 1.15 percent to 1.10 percent over the year. Nationally, return on average assets for all banks including those in Texas rose 5 basis points over the year, from 1.00 percent to 1.05 percent. District banks experienced weak first and third quarters before bouncing back with a very strong fourth quarter return of 1.25 percent (Chart 1).

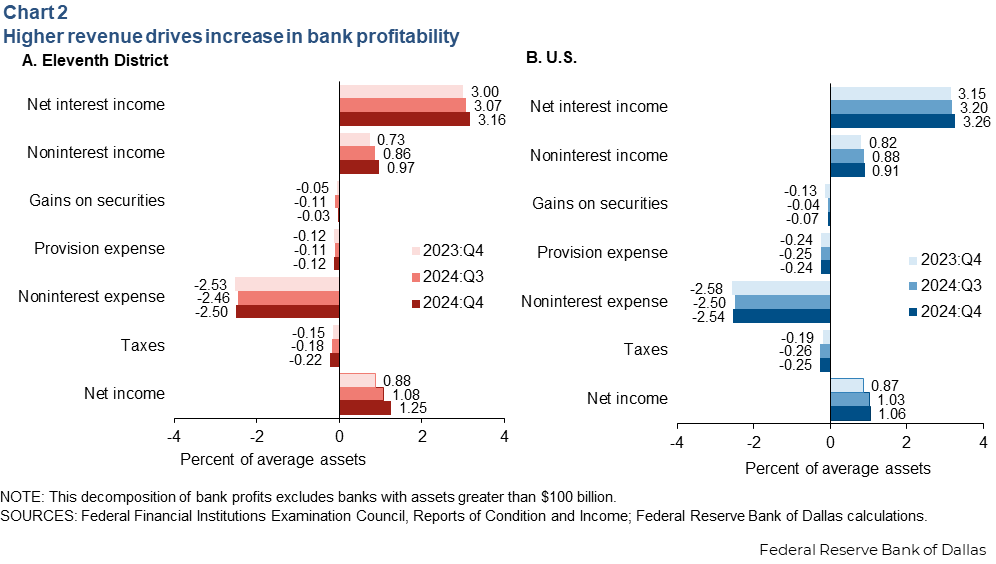

Banks make money from making loans or holding bonds that earn more than the interest they pay on their deposits, or from charging for services such as letters of credit or ATM and debit card transactions. Eleventh District banks were able to improve loan and fee returns in 2024, generating net interest income as a share of assets of 3.16 percent (up from 3.00 percent in 2023) and non-interest income of 0.97 percent (up from 0.73 percent) (Chart 2). At the same time, non-interest expenses such as wages, rent, information technology, advertising and other overhead fell slightly to 2.50 percent of assets over the year, from 2.53 percent in 2023.

Eleventh District banks generally outperformed U.S. banks. However, district institutions’ provisions expense rate, reflecting future possible loan losses, is roughly half the national rate.

When banks make loans, they must make upfront provisions because some of those loans will default. This is recorded as an expense to the bank when the loan is made, and the amount of provisioning expense each year can increase or decrease as banks expect higher or lower credit losses on their loans.

Eleventh District banks have enjoyed very strong performance on their loans in recent years, partly reflecting the region’s economic strength. However, if a slowdown or recession occurs, these banks may need to substantially increase this provisioning expense, which would become a drag on profits.

Balance sheet mix shifts toward loans and deposits; equity capital rises

Another way to measure profitability is net interest margin (net interest income divided by earning assets). In the Eleventh District, net interest margin rose 16 basis points to 3.40 percent in 2024 and remains relatively low (Chart 3). Nationally, it increased 12 basis points for the year to 3.49 percent.

This net interest margin increase in the Eleventh District occurred as banks lessened exposure to securities (which fell $12.8 billion in 2024, 7.1 percent) in favor of loans (which rose $12.2 billion, 3.1 percent) (Table 1). Loans typically earn higher interest income than securities. Equity capital (common stock, paid-in capital, preferred equity, retained earnings and other comprehensive income) rose 6.1 percent in district banks in 2024, less so nationally.

| Table 1: Balance sheets refocus on loans and deposits, reducing securities and wholesale funds | ||||

| Change, Dec. 31, 2023–Dec. 31, 2024 | ||||

| Eleventh District banks | U.S. banks | |||

| $, billions | Percent | $, billions | Percent | |

| Total assets | $6.6 | 1.0 | $159.0 | 2.3 |

| Loans | $12.2 | 3.1 | $155.0 | 3.4 |

| Securities | -$12.8 | -7.1 | -$40.0 | -2.8 |

| Cash | -$0.7 | -7.8 | -$3.0 | -4.3 |

| Other assets | $7.8 | 8.5 | $45.0 | 5.7 |

| Total liabilities | $2.5 | 0.4 | $118.2 | 1.9 |

| Deposits | $17.8 | 3.2 | $219.5 | 4.0 |

| Wholesale funds | -$15.0 | -36.0 | -$99.4 | -22.8 |

| Other liabilities | -$.36 | -3.6 | -$1.9 | -1.7 |

| Equity capital | $4.1 | 6.1 | $39.9 | 5.6 |

| NOTES: Data are for commercial banks with total assets less than $100 billion. The difference from 2023 to 2024 is shown in both dollars and percent change for Eleventh District and U.S. banks. Other assets for a bank may include premises, accrued income, tax assets, equity investments without readily determinable fair values or intangible assets such as goodwill. Wholesale funding refers to bank liabilities that are quick to arrange but are less stable than core deposits, such as federal funds, Federal Home Loan Bank advances and brokered deposits. Other liabilities for a bank may include accrued expenses, allowances for off-balance-sheet exposures, deferred tax liabilities or other borrowed money such as mortgages on premises owned by the bank. Equity capital equals total assets minus total liabilities. SOURCE: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Reports of Condition and Income. |

||||

On the funding side of the balance sheet, Eleventh District banks’ total liabilities in 2024 rose modestly, by $2.5 billion (0.4 percent); deposits increased $17.8 billion (3.2 percent) while wholesale funds fell $15 billion (36 percent). Wholesale funding refers to bank liabilities that are quick to arrange but are less stable and usually more expensive than core deposits, such as federal funds, Federal Home Loan Bank advances and brokered deposits.

Nationally, banks were even more successful in 2024 than district banks, shifting toward higher-earning assets and less expensive deposits. U.S. banks increased their loans $155 billion (3.4 percent) in 2024, while shrinking securities $40 billion (2.8 percent). On the funding side, they increased deposits $219.5 billion (4.0 percent) for the year and cut wholesale borrowing $99.4 billion (22.8 percent).

In other words, Eleventh District banks boosted their net interest income by changing their mix of earning assets without growing their overall earning assets very much. U.S. banks also changed their mix of earning assets but to a relatively smaller extent, while relying more on growing overall assets by funding new loans.

Overall, deposits shrank in 2022 and 2023 due to rising market interest rates, which increased faster than banks’ deposit interest rates. Further, concern about some banks’ unrealized losses on securities they owned may have also caused some depositors to move on during the Silicon Valley Bank upheaval of March 2023. For many banks, the rise in deposits in 2024 represents a rebalancing from the 2023 shock toward a more traditional funding composition.

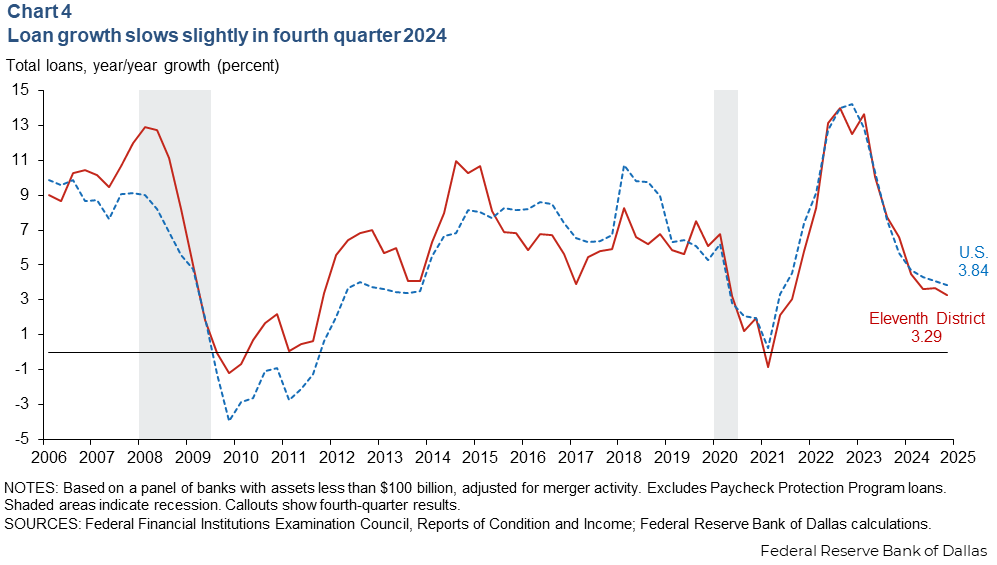

Loan growth eases in Eleventh District

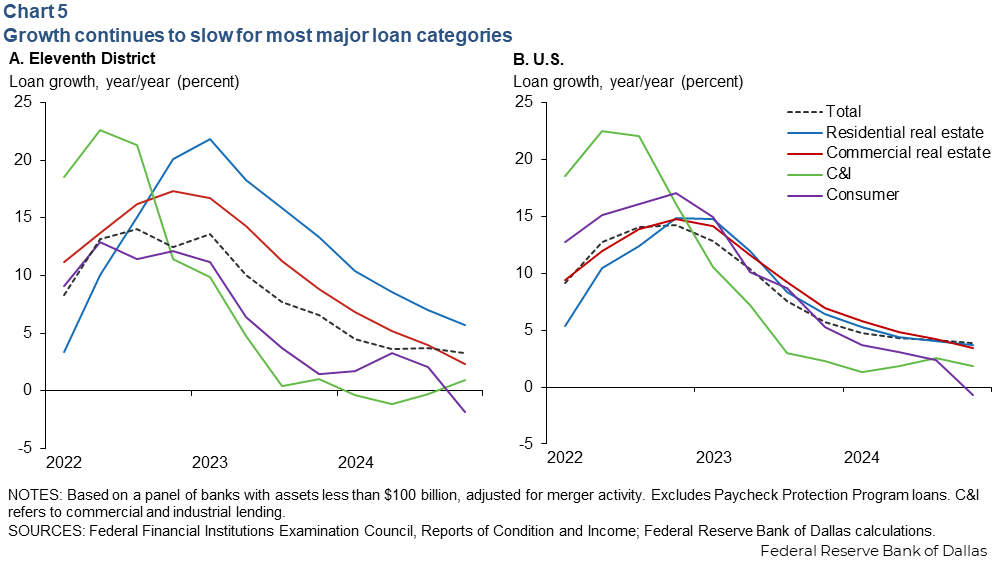

Diminished loan growth poses a challenge to district banks. Growth continued easing during 2024, remaining a steady 3.28 percent in the Eleventh District and 3.84 percent nationally (Chart 4). While this is below the average rate for bank lending in the past decade, it may simply be a return to more usual activity after extraordinarily high growth in 2022.

Loan growth within the district was concentrated in real estate (both residential and commercial). Meanwhile, drags on district loan growth came from consumer loans, which fell 1.85 percent in 2024, and commercial & industrial loans, which grew just 0.94 percent after a weak first half of the year (Chart 5).

Commercial & industrial lending includes loans to businesses, typically for shorter terms than real estate loans and at floating interest rates, with collateral other than real estate. Consumer lending provides financing for individual and household consumers, such as credit cards, personal loans or auto loans. Nationally, these two categories were the slowest in 2024, with commercial and industrial growth slipping to 1.83 percent and consumer lending contracting 0.67 percent.

Within commercial real estate lending, the notable drag in the Eleventh District was construction and land development lending, which fell $3.5 billion (7.2 percent) in 2024, while the overall category of commercial real estate lending grew $4.1 billion (2.3 percent).

Nationally, construction and development lending fell $13.4 billion (3.73 percent), while overall commercial real estate lending grew $61.4 billion (3.10 percent). All other categories of commercial real estate lending grew in 2024. Because construction and land development lending finances the building of new real estate assets, this reduction may mean less new supply of commercial real estate in the coming years. Reduced new inventory may support prices and loan quality in that sector.

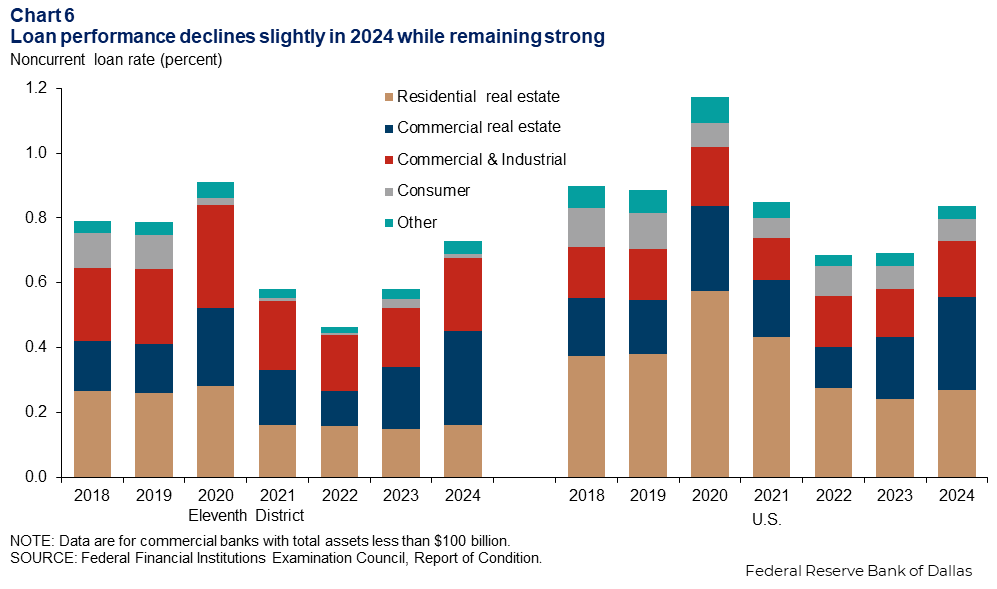

Loan quality remains historically high

Loan performance weakened slightly in 2024 but was strong overall (Chart 6). Noncurrent loans (those at least 90 days past due) remain below prepandemic levels but increased from 0.58 percent to 0.73 percent year over year in the Eleventh District, and from 0.69 percent to 0.84 percent nationally.

A reversion from historically low noncurrent rates is a positive development. Banks are in the business of taking credit risk to build the economy, and this represents a modest return toward historical levels, rising from the lowest levels in more than 20 years.

Commercial real estate was the main bank loan category to deteriorate. The noncurrent loan rate advanced to 0.10 percent of all loans. Commercial real estate grew increasingly weak each quarter in the Eleventh District and nationally since first quarter 2023. The sector deteriorated further nationally but was flat in the Eleventh District in fourth quarter 2024.

With businesses increasingly curtailing remote work options, the need for office space and accompanying retail shops may bring some support to commercial real estate borrowers. However, because of price declines of nearly 50 percent nationally from 2020 peak valuations, some office borrowers continue struggling in 2025 (Table 2).

| Table 2: Commercial property prices decline from recent peaks | ||||

| U.S. national commercial property prices, percent change as of January 2025 | ||||

| Past month | Past 12 months | From recent peak | From April 2020 | |

| All types | 0.53 | 0.30 | -11.14 | 13.16 |

| Multifamily | 0.65 | -1.57 | -17.98 | 11.78 |

| Retail | 1.45 | 5.05 | -4.37 | 16.97 |

| Industrial | -0.05 | 3.38 | -0.16 | 44.86 |

| Office–central business district | -0.62 | -10.02 | -49.88 | -48.48 |

| Office–suburban | 0.05 | -1.46 | -18.32 | -4.21 |

| NOTE: U.S. national data through January 2025.

SOURCE: MSCI, Real Capital Analytics. |

||||

At the same time, markedly slower rent growth and rising apartment vacancy rates may pressure multifamily commercial real estate borrowers. Industrial and retail commercial real estate have performed strongly in recent years, but climbing vacancy rates and concerns about tariffs and trade disruptions could pose downside risk to industrial loans.

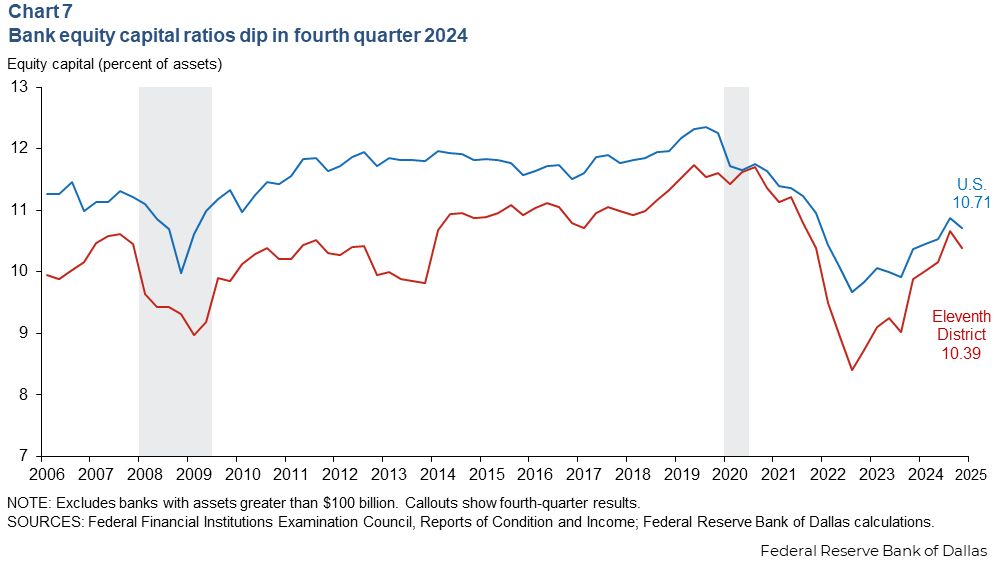

Bank capital levels dip in fourth quarter

Equity as a percent of total assets for district banks fell slightly in the fourth quarter, with higher retained earnings offset by additional unrealized losses on available-for-sale securities as interest rates rose (Chart 7).

However, this decline is small relative to the substantial rise in banks’ equity capital since mid-2022. Bank regulatory capital ratios remain well above required minimum levels. If long-dated bond yields continue rising in 2025, bank equity targets could face headwinds.

District banks start 2025 strong, face economic challenges

District banks entered 2025 with strong profitability and loan quality. Throughout 2024, banks managed to pivot their balance sheets toward new loans and build their core businesses, while reducing reliance on wholesale funding sources that served as stopgaps during the banking difficulties of 2023. Yet, vulnerabilities remain as interest rates continue to fluctuate and banks’ loan portfolios normalize from extraordinarily benign conditions.

A sustained trade war could pressure the U.S. economy through both lower economic growth and higher inflation. Much Eleventh District trade activity is with Mexico, which has been spared many of the most severe recent tariff policies.

Immigration and energy developments—declining immigration and a steep fall in energy prices—will also challenge local economic conditions. However, Eleventh District banks do not have disproportionately high exposure to direct lending in the energy sector. Those capital investments are large and typically syndicated through several banks nationally. Thus, oil price weakness will affect district banks indirectly.

Eleventh District banks navigated 2024 by focusing on their core strengths. Thus far, 2025 has offered a historic degree of uncertainty, and banks may find it prudent to navigate this uncertainty by continuing to focus on their core banking business, carefully examining their credit outlook and loan provisioning, and building on the strength of still-robust earnings.

About the author