Anticipatory discount window stigma

Central bank lending facilities, such as the Federal Reserve’s discount window, provide a key line of defense against financial instability. These facilities allow banks to readily borrow cash when needed, so they can continue to serve the economy in the face of unexpected shocks or market-wide funding shortfalls. They can give depositors confidence that banks have ready access to funds, reducing the motivation to participate in bank runs. And, they establish a backstop that can keep small shocks from spiraling into major stresses.

Yet observers often assert that stigma—a perception that depositors, investors or others will penalize an institution for borrowing from the discount window—keeps banks from borrowing when they should, making the facilities less effective. Some analysts propose policy and design changes to reduce stigma, while other research finds that removing stigma may be difficult.

I argue that some harms of discount window stigma can be mitigated regardless of whether stigma itself persists. I distinguish between two types of stigma. “In-the-moment stigma” arises when a bank faces an immediate funding need but fears the consequences of meeting that need by borrowing from the discount window. “Anticipatory stigma” arises when a bank bases business decisions on a belief that stigma would deter it from using the discount window to meet potential future funding needs. Anticipatory stigma reduces the discount window’s effectiveness because borrowing requires operational preparations, which a bank may see as not worth the effort if it anticipates that stigma would ultimately deter it from borrowing.

While there are examples from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of in-the-moment stigma apparently deterring discount window use, more recent challenges at the window have appeared to result more from anticipatory stigma.

In March 2023, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank came under severe stress and sought to borrow from the discount window. The firms were inadequately prepared, limiting the speed and amount of funding each could obtain. (However, reviews of these banks’ failures emphasize many weaknesses beyond operational readiness to borrow from the window, and discount window funding cannot save a bank whose business model or risk management is more fundamentally flawed. A Federal Reserve Board review found that “While stronger operational capacity … would likely not have prevented SVB’s failure, it could have facilitated a more orderly resolution.”[1])

The harms of anticipatory stigma could be mitigated by changing the cost-benefit trade-off that a bank faces in deciding whether to prepare to access the window. Observers have described how regulators and supervisors could require or incentivize banks to maintain some level of readiness. Alternatively, the Federal Reserve could conceivably simplify the steps required to prepare. Some of these mitigants could make it easier for banks to decide to borrow and, therefore, lessen the harms of in-the-moment stigma as well. Thus, the discount window’s effectiveness could be enhanced through a focus on operational readiness regardless of whether stigma persists.

The rest of this note has four parts. The first explains the need for operational readiness at the discount window. The second part describes the potential for anticipatory stigma in greater detail. I distinguish between time-consistent anticipatory stigma, where the bank is correct in anticipating that it would not want to borrow should a funding need arise, and time-inconsistent anticipatory stigma, where the bank’s views on the discount window in a funding crisis differ from those it expects to have ex ante.

The third part reviews steps that observers have suggested could encourage banks to increase operational readiness. The note concludes by outlining benefits and costs of such steps from a public policy perspective. Regulations requiring readiness may have greater benefit when anticipatory stigma is time inconsistent than when it is time consistent.

Operational readiness at the discount window

Appropriately prepared banks can obtain liquidity from the discount window in as little as a few minutes. However, discount window loans are not handshake agreements, and preparation is crucial in three respects: legal agreements, collateral and procedures for requesting a loan.

A bank that borrows from the discount window must execute a legal agreement promising to repay. The agreement is a blanket document that can be executed in advance and covers all loans requested thereafter. A bank typically needs to have its attorney review the agreement and its board of directors authorize execution.

The Federal Reserve Act requires that a discount window loan be secured to the satisfaction of the district Reserve Bank making the loan. A borrower must, therefore, provide the Reserve Bank with a security interest in sufficiently valuable collateral.

For collateral consisting of securities, such as government bonds, the Reserve Bank obtains a perfected security interest through control: The borrower transfers the collateral to an account that the Reserve Bank controls at a custodian or at the Reserve Bank itself.

If the borrower has set up the necessary account in advance, pledging securities that the borrower fully controls takes only minutes as long as borrowing firm personnel are familiar with the required procedures. The value of securities collateral is relatively straightforward to assess using market prices, and the Reserve Bank can typically assign a lendable value nearly simultaneously with the pledge.

For less-liquid collateral, such as mortgages or other whole loans, depository institutions typically establish a borrower-in-custody (BIC) loan pledging arrangement with the Reserve Bank. Establishing a BIC arrangement can take several weeks, as the Reserve Bank verifies the borrowing bank’s internal controls, documentation practices and other factors. Once this one-time setup process is complete, the Reserve Bank obtains a perfected security interest in loan collateral through receipt of a collateral list from the borrower, coupled with a broad one-time Uniform Commercial Code filing that the Reserve Bank is satisfied will take priority over other creditors.

Reserve Banks typically value loan collateral with a pricing model based on various loan characteristics. The borrower must transmit information on those characteristics to the Reserve Bank for input into the model. The lendable value of collateral is generally less than the current market value to account for the risk that the collateral’s value may fall.

If a depository institution faces a pressing need for funds but a BIC arrangement is not in place or the firm is unable to immediately transmit complete details on loan characteristics, a Reserve Bank can sometimes accept a pledge of loan collateral without the usual level of detail. However, the Reserve Bank may need to protect itself against the risk of loss in such cases by applying a larger haircut, reducing the amount that a depository institution can borrow against the collateral.

Obtaining a discount window loan also requires authorized personnel at the borrowing bank to follow specified procedures to make the request by phone or through an electronic portal. While these procedures are straightforward for personnel who have experience with them, banks can face challenges if they are inexperienced or if authorized and experienced personnel are not on duty when the bank seeks a loan.

Additionally, if collateral already pledged to the Reserve Bank is insufficient to back the desired loan, the borrower must follow appropriate procedures to pledge more collateral—again, a more straightforward task for personnel who have experience with it. Moreover, when a bank has other collateralized funding sources, it can take time to remove collateral from platforms used by those sources or persuade those lenders to release claims so the collateral can be pledged to a Reserve Bank.

In sum, depository institutions are better positioned to quickly obtain discount window loans in the amount needed if they take steps well in advance of any funding need to execute legal agreements, make collateral pledging arrangements, enable the Reserve Bank to value the collateral and practice the procedures for requesting a loan and pledging additional collateral.

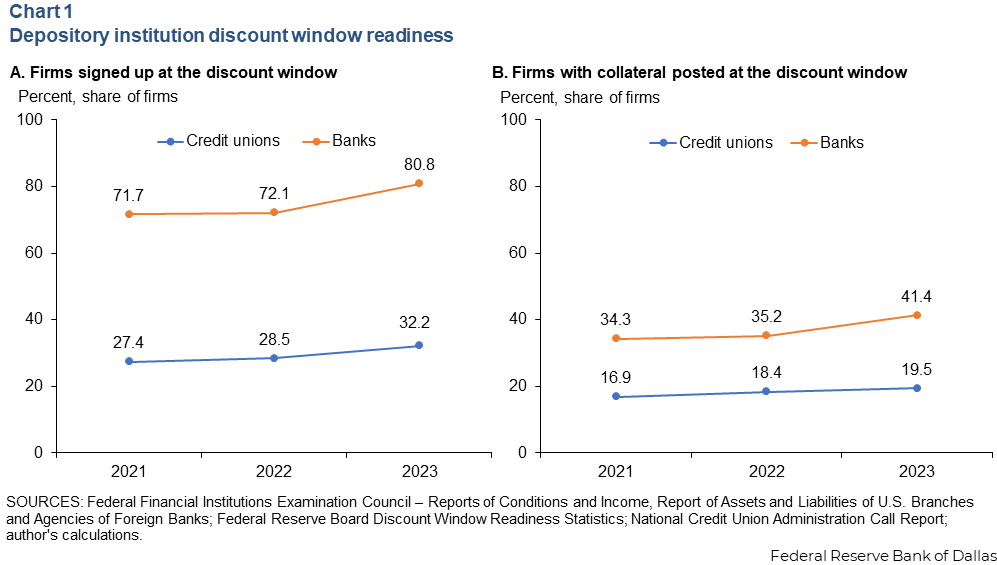

As shown in Chart 1, more banks and credit unions prepared to borrow from the window by signing the legal agreement and pledging collateral following the 2023 banking stresses. Nevertheless, as of the end of 2023, a majority of firms had not pledged collateral at the window.

Discount window stigma and time consistency

Discount window stigma exists when a bank perceives nonpecuniary costs of discount window borrowing that make the firm willing to pay a premium to avoid the window by borrowing from another source.

Stigma may arise in the moment when a bank faces a funding need and considers a source to meet it, or anticipatorily, when a bank develops its plans for meeting potential future funding needs. (This is a broad definition of stigma. It encompasses situations where a bank’s decision not to borrow from the window raises the bank’s costs but does not lead to its failure, as well as cases where the bank is not itself under funding stress but would intermediate funding to another market participant in need.)

In-the-moment stigma is usually attributed to bank executives’ perception of potential adverse reactions by depositors, investors, bank examiners or higher levels of management. By law, discount window loans are publicly reported with a two-year lag, but a bank might worry that its borrowing could be detected more quickly, potentially triggering a run or causing investors to sell the bank’s stock. In addition, although Federal Reserve leaders have emphasized that “using the discount window is not an action to be viewed negatively,”[2] a banker could still believe that use of the window might reduce examiners’ or more-senior executives’ confidence in the quality of the firm’s liquidity risk management.

The degree to which in-the-moment stigma reduces discount window use and effectiveness depends in part on the reason for the funding need and, relatedly, the policy purpose that the discount window is conceived as serving.

In addition to supporting financial stability, the window plays a role in monetary policy implementation by establishing a backstop interest rate at which banks can borrow if market rates rise higher than the Federal Open Market Committee intends.

While banks are unlikely to be willing to fail rather than incur whatever stigma may be associated with discount window borrowing, those with access to other, pricier funding sources might be willing to pay up to avoid stigma. Paying higher rates at other funding sources would undermine the window’s effectiveness for rate control. However, the window’s rate control role receded in prominence following the GFC, with the transition to an ample reserves policy implementation regime in which instances of rate pressure are much less frequent.

Anticipatory stigma arises from the need for operational preparations to most effectively access the discount window. A bank considering whether to invest time and money in preparations may weigh those costs against the benefit of preparation.

The benefit is the ability to receive a discount window loan if a funding need arises. The value of this benefit depends on both the likelihood of a funding need and the likelihood that the bank would use the discount window in the event of need. If a bank believes in-the-moment stigma would lead it to choose not to borrow from the window in some (or all) scenarios, the benefit of preparation is reduced (or eliminated). The bank might then decide not to prepare, a decision that would impede its access to the window should a need arise.

A bank’s anticipation of discount window stigma may or may not be accurate.

Examples exist in which banks that were prepared to borrow from the window evidently chose not to due to stigma. The Federal Reserve established the Term Auction Facility (TAF) in 2007, as part of its response to the GFC. Banks could bid for Federal Reserve loans in a competitive auction. The TAF’s design was intended to reduce stigma relative to the discount window, but in all other respects, it was no more attractive than the window.

Over the TAF’s 27-month life, banks bid an average of 44 basis points more for TAF loans than the posted discount window rate—a direct example of paying a premium to avoid the window. This outcome demonstrates that in-the-moment stigma has existed at some times, so a bank acting on the basis of anticipated stigma might have accurate expectations. If a bank failed to prepare and then, due to stigma, did not want to borrow from the window when a funding need arose, that bank would exhibit time-consistent anticipatory discount window stigma.

On the other hand, if a bank’s funding need became sufficiently severe, it would almost certainly prefer to borrow from the window and suffer whatever consequences there might be with depositors, investors and examiners rather than fail and go out of business. Bank executives who are confident their banks will not fail may not fully appreciate the possibility of such a scenario.

Cases such as those of SVB and Signature demonstrate that depository institutions sometimes do not adequately prepare to use the discount window yet seek loans when severe stress arises. To the extent the lack of preparation resulted from perceptions of stigma, these outcomes are evidence of time-inconsistent anticipatory discount window stigma.

Increasing discount window readiness in the face of anticipatory stigma

Research suggests that in-the-moment stigma can be difficult to redress once it exists. Removing anticipatory stigma might be even more difficult as it would require changing bankers’ thinking about potential future scenarios rather than immediate funding needs. But because the harm of anticipatory stigma is a failure to prepare, this harm can be mitigated even if stigma itself persists. If a bank is adequately prepared to borrow, in-the-moment stigma might still cause it to choose not to borrow, but at least it will have the option.

Banks could be encouraged to prepare to borrow from the window by increasing the benefits of preparation or by reducing the costs of preparation. Policymakers, scholars, industry experts and other observers have suggested options along both of these lines.[3]

Increasing the benefits of preparation: Proposals have envisioned that regulators could require that banks prepare to borrow from the window, or, relatedly, supervisors could further take banks’ operational readiness into account when evaluating their liquidity risk and liquidity risk management.[4] Preparations would then have the benefit of keeping the bank in compliance with regulations or receiving good supervisory ratings, avoiding the negative consequences of noncompliance or low ratings. Questions that have been proposed for consideration by regulators or supervisors include:

- Has the bank executed a legal agreement for discount window borrowing?[5]

- How much collateral has the bank pledged to the Reserve Bank?[6]

- Has the bank recently tested and practiced procedures for requesting a loan and pledging additional collateral?[7]

Alternatively, observers have suggested that regulators or supervisors could provide an incentive to prepare to borrow from the discount window by relaxing other liquidity requirements for banks that prepare. For example, discount window access for well-prepared banks could count toward regulatory and supervisory liquidity requirements, even if the underlying collateral is not liquid.[8] However, such incentives could present trade-offs. They might diminish banks’ motivation to self-insure by maintaining liquid assets or access to private market funding, or they might reduce banks’ incentive to internalize the costs to the financial system of the liquidity risks they take.

Reducing the costs of preparation: Commentators have suggested that the Federal Reserve could seek to simplify the processes for establishing legal agreements and collateral pledging arrangements, pledging collateral and requesting loans. While such steps would need to ensure that discount window loans remain appropriately secured, simplified processes would reduce the effort required to prepare to borrow. Enhanced processes for pledging collateral and requesting loans would also streamline actual borrowing. Possibilities that have been proposed include:

- Requiring banks to sign the legal agreement for discount window borrowing at the time they sign the legal agreement to establish a master account at the Federal Reserve, so that separate legal review and board approval would not be needed.[9]

- Enhancing electronic tools for pledging collateral.[10]

- Automating the process for requesting and approving loans, such as by automatically converting adequately collateralized daylight overdrafts into discount window loans at the end of the day.[11] (A healthy bank is allowed to send outgoing payments in excess of the amount in its Federal Reserve account, up to certain limits, with the expectation that it will repay the funds by the close of business. Such a situation is known as a daylight overdraft.) With more automation, a bank would not need to request a discount window loan or practice the procedure for doing so. A bank would still need to remain ready to pledge adequate collateral.

Benefits, costs of mitigating harms of anticipatory stigma by encouraging preparation

The primary benefit of encouraging banks to prepare to borrow from the discount window is that well-prepared banks will be able to borrow when such borrowing would support their safety and soundness, the stability of the financial system or interest rate control. However, if in-the-moment stigma deters banks from borrowing even when they are prepared, that benefit is reduced. Thus, the benefit of encouraging preparation may be larger when anticipatory stigma is time inconsistent—that is, when banks’ views of the discount window at the time funding is needed differ from what they anticipated beforehand—than when anticipatory stigma is time consistent.

Time inconsistency also adds a dimension to the benefits of encouraging preparation despite anticipatory stigma. When a bank’s current anticipation of its future actions differs from what it will wish to do in the future, there is a conflict of interest between the bank’s current management and future management (including if the same individuals serve in management at both times but their preferences change). That conflict of interest may be costly for the bank itself, which arguably should give bank management an incentive to resolve the conflict. However, management’s inability to resolve the conflict could create negative externalities for the financial system, taxpayers and society as it might propagate stress or generate losses for the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. if a bank fails. Policies to encourage preparation could resolve the conflict of interest in a way that corrects these negative externalities.

More generally, in deciding whether to prepare, an individual bank would weigh its private costs and benefits of preparation and would not necessarily consider potential spillovers to the financial system from its lack of access or failure to borrow. If a bank’s inability to borrow could destabilize other financial institutions, such as by precipitating bank runs or propagating liquidity stress to other firms, the benefits of preparation for the system would exceed the private benefits to any one firm.

The author thanks his Federal Reserve System colleagues for helpful discussions and comments.

Notes

- See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Review of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank,” April 2023, pp. 5 and 60; Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., “FDIC’s Supervision of Signature Bank,” April 28, 2023, p. 15.

- Michael S. Barr, “The Importance of Effective Liquidity Risk Management,” speech at the ECB Forum on Banking Supervision, Frankfurt, Germany, Dec. 1, 2023.

- See, for example, Lorie K. Logan, “Remarks on liquidity provision and on the economic outlook and monetary policy,” delivered at the Texas Bankers Association, San Antonio, May 18, 2023; Michael S. Barr, “On Building a Resilient Regulatory Framework,” remarks at Central Banking in the Post-Pandemic Financial System 28th Annual Financial Markets Conference, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Fernandina Beach, Florida, May 20, 2024; Michael J. Hsu, “Building Better Brakes for a Faster Financial World,” remarks at Columbia Law School, New York, Jan. 18, 2024; Susan McLaughlin, “Lessons for the Discount Window from the March 2023 Bank Failures,” Yale Program on Financial Stability, Sept. 19, 2023; Group of 30 Working Group on the 2023 Banking Crisis, “Bank Failures and Contagion: Lender of Last Resort, Liquidity, and Risk Management,” report, January 2024; Bill Nelson, “Design Challenges for a Standing Repo Facility,” Bank Policy Institute, Aug. 13, 2019; Bill Nelson, “10 Pitfalls to Avoid When Designing Any Additional Liquidity Requirements,” Bank Policy Institute, Feb. 26, 2024.

- Currently, as described in the “Addendum to the Interagency Policy Statement on Funding and Liquidity Risk Management: Importance of Contingency Funding Plans (July 2023),” if a bank’s contingency funding plan includes the discount window, the bank is expected to consider regularly testing its discount window access with small-value transactions. On proposals for additional expectations, See Group of 30 Working Group on the 2023 Banking Crisis (2024), Hsu (2024), Logan (2023) and McLaughlin (2023).

- See Logan (2023).

- See Barr (2024), Group of 30 Working Group on the 2023 Banking Crisis (2024) and McLaughlin (2023).

- See Hsu (2024), Logan (2023) and McLaughlin (2023).

- See Hsu (2024) and Nelson (2024).

- See McLaughlin (2023).

- See McLaughlin (2023).

- See McLaughlin (2023) and Nelson (2019).

About the authors