Young workers’ employment drops in occupations with high AI exposure

Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to raise productivity and economic growth, but there is concern it will replace workers or at least disrupt labor markets and temporarily squeeze employment during the transition from old occupations to new ones.

In recent years, unemployment has gradually ticked up, and job searchers report increased difficulty finding new work. Is this related to AI?

Consistent with other analyses, we find some correlation across occupations between employment declines and AI exposure, but only for younger workers. This suggests only a slight impact on the aggregate unemployment rate so far. Lower employment for young workers in AI-exposed occupations is primarily driven by a decline in people transitioning directly from out of the workforce into employment rather than by layoffs or low job-finding rates among the unemployed.

Young employment declines in jobs with high AI exposure

Workers age 22 to 25 in the most AI-exposed occupations have experienced a 13 percent decline in employment since 2022, a recent study by researchers at Stanford University found. Meanwhile, employment for less exposed or more experienced workers has been steady or even increasing.

The authors use payroll data on 25 million workers from ADP, the largest payroll software provider in the U.S., and adopt a measure developed by researchers Tyna Eloundou, Sam Manning, Pamela Mishkin and Daniel Rock to score occupations by AI exposure and assign each to a quintile.

While the proprietary ADP data offers a real-time, large-scale panel of payrolled workers, we use the U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Survey public microdata that have a rotating panel of around 100,000 individuals. Though it has a smaller sample size, the Current Population Survey has the advantages of extending further in time and capturing longitudinal information on the flows in and out of occupations.

Partitioning an already small sample by age and AI exposure can result in relatively few observations in a given age-by-AI-exposure group, leading to noisy estimates. To mitigate this effect, we take 12-month moving averages of employment and labor transition rates.

We use the same AI exposure measure that scores occupations from 0 (no AI exposure) to 1 (full AI exposure). We classify occupations as members of the least, moderate or most AI exposure categories according to the tertiles (a statistical grouping of a dataset into thirds) of the employment-weighted distribution of scores in 2024. This ensures that occupations remain in the same AI exposure categories over time. The following are the three most common occupations in each category:

- Least AI exposure: cashiers; janitors and building cleaners; laborers and freight, stock and material movers.

- Moderate AI exposure: driver/sales workers and truck drivers; retail salespersons; elementary and middle school teachers.

- Most AI exposure: first-line supervisors of retail sales workers; secretaries and administrative assistants; customer service representatives.

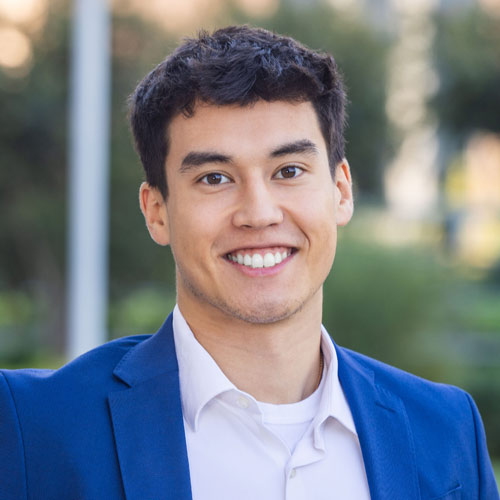

We further divide workers by age, categorizing them as young (ages 20–24) or prime-age (ages 25–55), to yield six age-by-AI-exposure groups (Chart 1).

As with the ADP data, the Current Population Survey data do not give much indication of widespread labor market disruption due to AI. However, the data show some decline in employment for young workers in the most AI-exposed occupations. Share of employment for these occupations slips from 16.4 percent in November 2022, when ChatGPT was released, to 15.5 percent in September 2025.

Employment in other age and occupation groups has either risen or is roughly steady. Because workers age 20 to 24 are only about 9 percent of the labor force, this 0.9 percentage-point decline for young workers most exposed to AI likely explains little of the increase in the aggregate unemployment rate.

Layoffs, job finding among unemployed don’t explain pattern

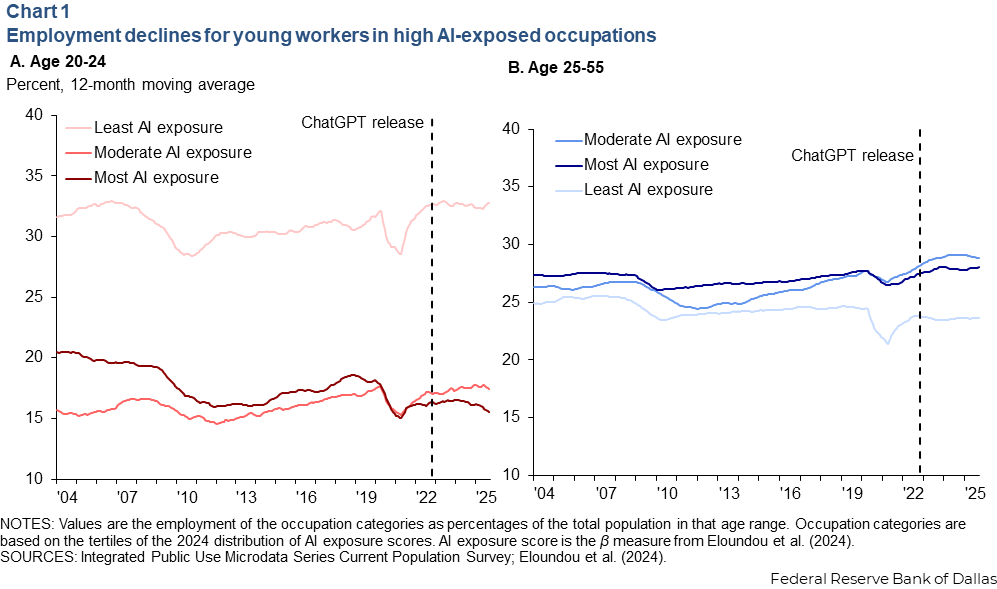

There hasn’t been an increase in young workers in high AI exposure occupations entering unemployment from employment (Chart 2). Moreover, there doesn’t appear to be a pattern across AI exposure for either young or prime-age workers. Thus, layoffs don’t appear to be a cause for rising young worker unemployment rates.

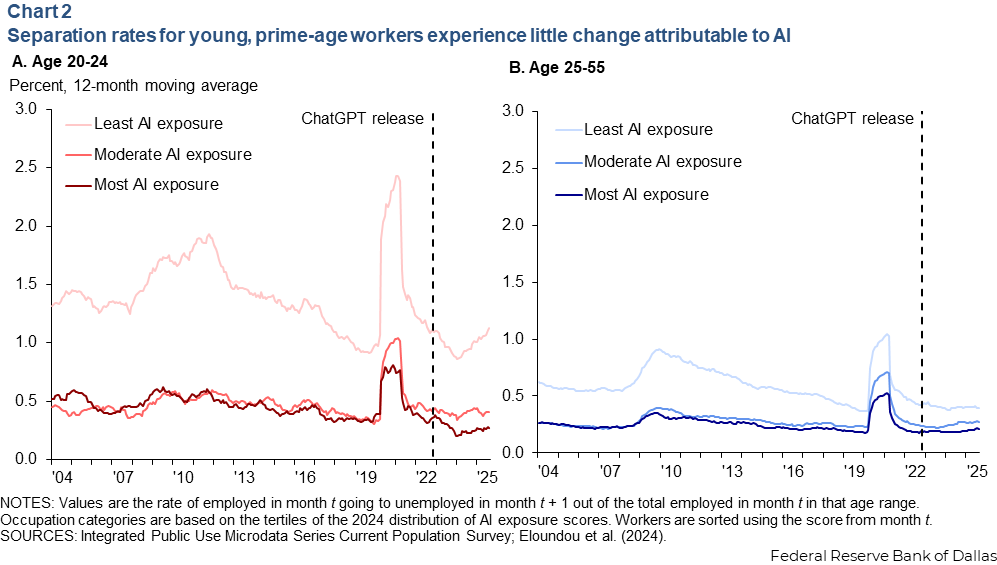

Additionally, among the unemployed, the young, most AI-exposed group’s job finding rates track those of the other groups. All six groups experienced a decline over this period (Chart 3).

For all groups besides the young, most AI-exposed group, these declines follow considerable increases in job finding during the postpandemic recovery of 2022. Currently the job finding rates of all groups are near or slightly below their respective 2016–19 averages.

Job finding rate of labor market entrants illustrative

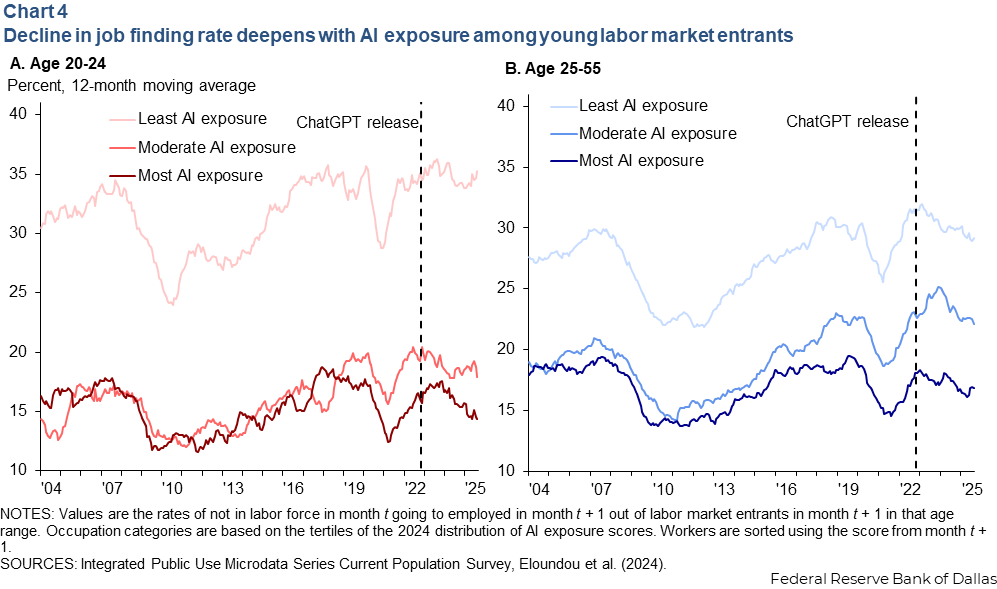

Similar to the job finding rate of the unemployed, the rate for labor market entrants has generally declined since November 2022 (Chart 4). This is the rate that workers entering the labor force find work in the first month in the given occupation categories rather than becoming unemployed.

Among young labor market entrants, the job finding rate has held steady only for jobs with low AI exposure, while it has declined for groups with higher AI exposure since November 2022. Since its recent peak in November 2023, the job finding rate of the young, most AI-exposed group has declined by more than 3 percentage points. Looking at past business cycles, the data confirm this isn’t a typical cyclical phenomenon.

Thus far, lower employment in high AI exposure occupations for young workers is mainly driven by a lower inflow, particularly among those out of the labor force, rather than by an outflow.

In the Current Population Survey, the occupation of unemployed workers is recorded as their most recent occupation, not necessarily the occupation for which they seek work. This implies that even if AI has somewhat increased unemployment for young workers, it may not be visible in unemployment rates by occupation.

For example, if AI adoption prevents a computer science graduate from ever finding a job as a computer programmer, that individual’s occupation would be recorded as their most recent position rather than as an unemployed programmer. For this reason, we refrain from using the occupation of unemployed workers to identify AI exposure.

AI impact small and uncertain, but could grow

There appears to be lower employment for young workers in occupations with the most exposure to AI, but so far, the aggregate impacts are small and subtle. If all the decline in employment for the young, most AI-exposed workers translated into unemployment, it would be responsible for only a 0.1 percentage point rise in aggregate unemployment since November 2022.

An important caveat is that this pattern may not be causal and could be driven by some other factor correlated with AI exposure, such as education. Still, though the effect of AI on labor outcomes has so far appeared subtle, its future impact could be much greater. This is an early sign to watch as AI’s development continues.

About the authors