Will AI replace your job? Perhaps not in the next decade

Recent rapid improvements in the capabilities of artificial intelligence (AI) have raised concerns about these technologies’ impact on employment, specifically, the rollout of generative AI models such as ChatGPT that can create new work product from existing inputs.

Unease about new technologies displacing workers is not new. It can be traced back at least to the earliest days of automation during the Industrial Revolution. Technologies such as the steam engine and the dynamo inspired similar fears in their day, as did information technology when computers were first introduced.

But the jobs AI is expected to touch in the years to come are different from those impacted by previous waves of technological change.

The ultimate effects of AI on the workforce will depend on the extent to which AI augments (or complements) rather than automates (or substitutes for) workers’ tasks. Will this new technology aid workers or replace them?

To understand AI’s possible occupational implications, we explore the workforce effects of the last technological advance thought to put jobs at risk: computerization. We look at the impact on occupations believed vulnerable to computerization 10 years ago and what that analysis may say about job vulnerability to generative AI today.

First, computers loomed over occupations

Before the advent of AI, the main workforce concern was whether computerization would displace jobs. A widely cited University of Oxford study by Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne, first circulated in 2013, examined the susceptibility of different occupations to computerization. It ultimately determined that 47 percent of total U.S. employment was at risk in 2013.

The authors assigned a probability of computerization to each of 702 occupations. Jobs deemed most at risk included telemarketers, title examiners, sewer workers, mathematical technicians, insurance underwriters, watch repairers, cargo and freight agents, tax preparers, photographic process workers, new account clerks, library technicians and data entry keyers, all with a 99 percent likelihood of computerization.

Among those deemed least at risk were recreational therapists, occupational therapists, health care and social workers and choreographers. All had a less than a half-percent likelihood of computers taking over.

Move over, here comes AI

A decade later, with the November 2022 release of ChatGPT and subsequent rapid advance of generative AI since then (DeepSeek, Stargate, Manus, for example), AI has overtaken computers as a leading risk to long-standing occupations.

A recent study by Edward W. Felten, Manav Raj and Robert Seamans attempts to identify occupations most vulnerable to automation from generative AI from both the perspective of language modeling (learning language and creating sentences after analyzing huge amounts of existing text) and image generation (creating images based on assimilation of large data sets) in a similar fashion to the earlier work by Frey and Osborne. Both studies identify occupations by the same occupation codes, making these two measures easily comparable.

The AI study authors created two scales for automation risk: from language modeling and image generating AI, labeling hundreds of occupations accordingly. The jobs identified as most susceptible to automation by language modeling AI include telemarketers, many types of teachers, sociologists, political scientists and arbitrators.

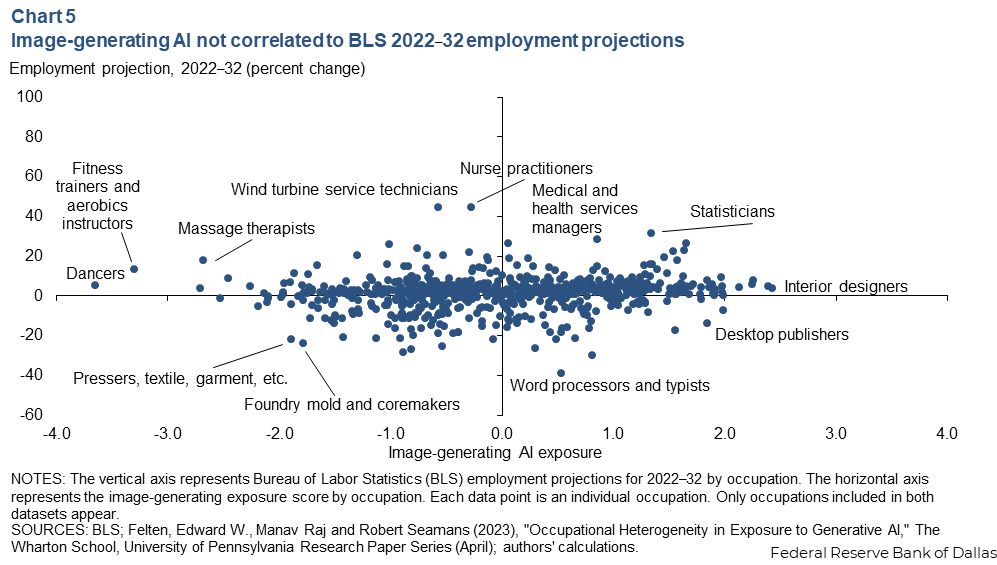

The jobs identified as most susceptible to automation by image generating AI include interior designers, architects, chemical engineers, art directors, astronomers and mechanical drafters.

Computerization, AI threaten different jobs

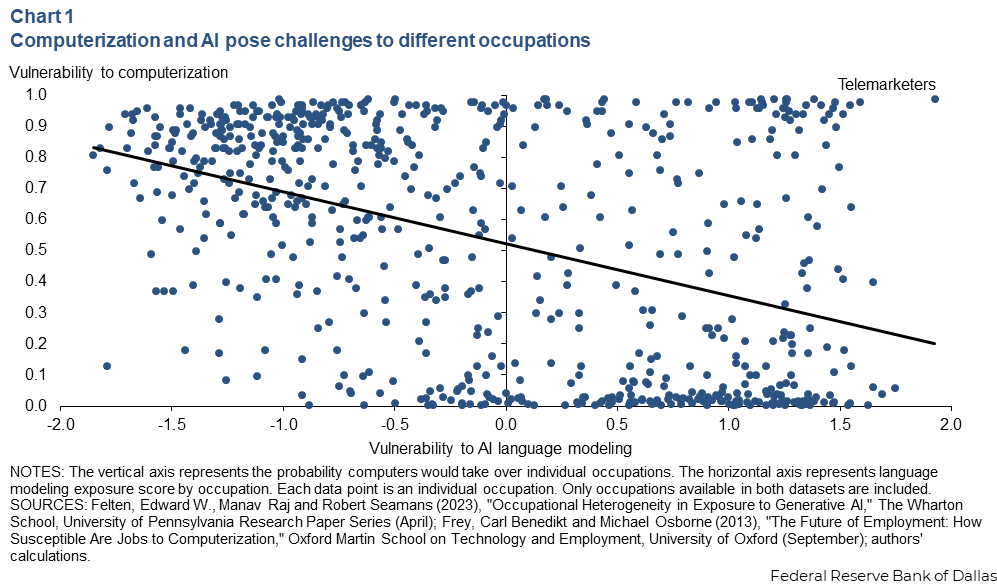

Comparing the occupations thought to be most likely to be computerized a decade ago with those most likely to be automated by AI today, the lists vastly differ (apart from telemarketers) (Chart 1).

The risks to specific occupations from earlier computerization and AI language modeling appear little correlated. The results for image-generating AI are similar. Today’s at-risk occupations aren’t the same ones threatened earlier.

Bureau of Labor Statistics offers 10-year employment projections

Every year, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) issues 10-year projections of employment in detailed occupations. The most recent set of projections was published in August 2024 covering 2023 to 2033. The BLS assumes that “labor productivity and technological progress will be in line with the historical experience” but recognizes that recent AI advances could cause the future to differ greatly from the past. These projections have historically been fairly accurate.

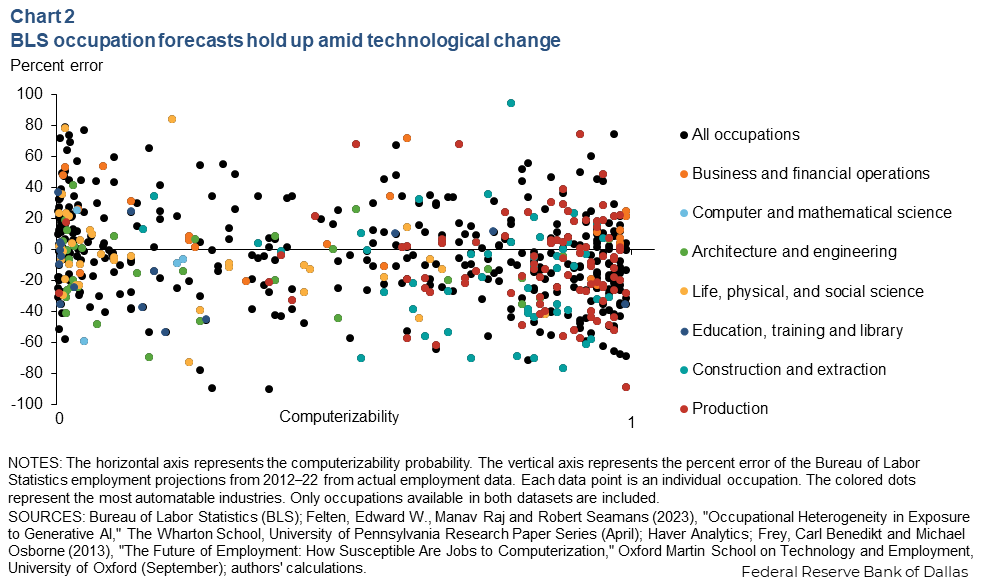

We looked at previous projections to better understand when they proved more or less accurate amid major technological change. We asked whether there is any evidence that the BLS’ misses by occupation were somehow related to the susceptibility of that occupation to computerization, as estimated by Frey and Osborne (Chart 2).

To the extent that the BLS projections missed the mark, anticipation of computerization doesn’t appear to have been the cause. The colored dots in Chart 2 represent occupations classified as being most susceptible to generative AI automation by Felten, Raj and Seamans. Again, there is little correlation with the BLS projection errors.

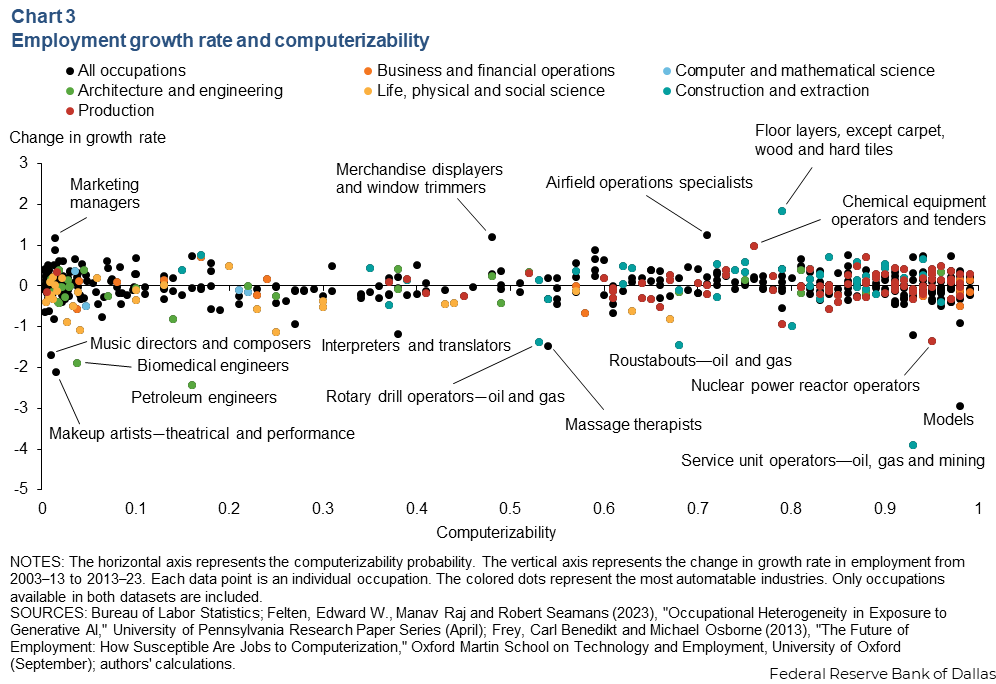

Considering this question from a different angle, we looked at whether changes in the growth rate of occupations from 2003–13 to 2013–23 were correlated with Frey and Osborne’s measures of computerizability (Chart 3).

Again, there is no correlation between an occupation’s change in growth rate and its susceptibility to computerization. Charts 2 and 3 together, thus, point to the idea that Frey and Osborne’s computerizability concerns did not have as significant an effect on the workforce as perhaps anticipated.

Alternatively, the charts suggest that the BLS methodology for long-term employment projections at the occupational level is relatively robust at incorporating major technological innovations.

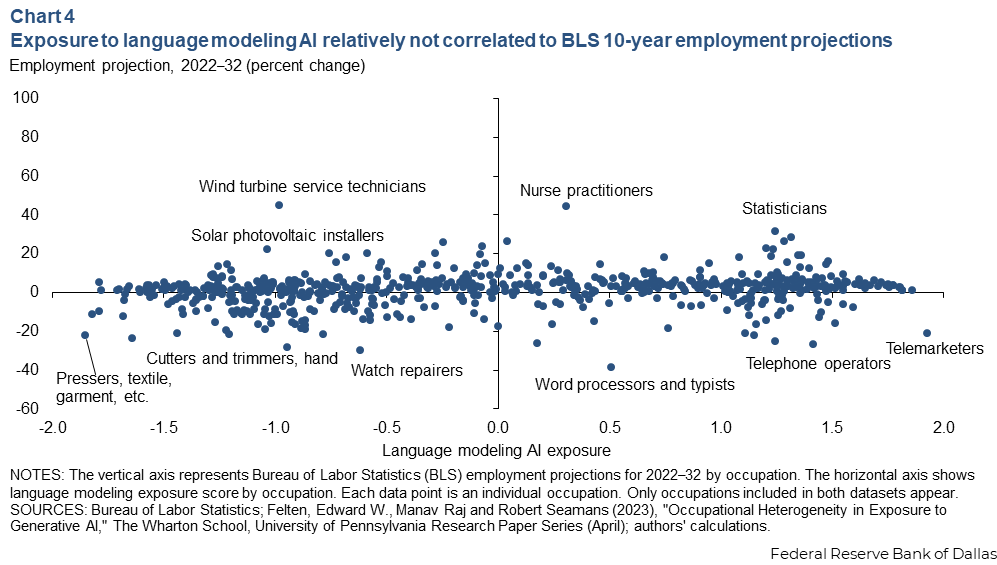

Looking ahead, to see if AI might yield different results, we explored the correlation between Felten, Raj and Seamans’ measure of exposure to language modeling AI versus the BLS 2022–32 employment projections (Chart 4).

The measure of exposure to image generating AI vs. the BLS 2022–32 employment projections shows similar results (Chart 5).

The lack of correlation in both charts demonstrates the BLS’ conservative approach to including AI in its workforce projections. For example, employment in some occupations, such as statisticians in Chart 4, is expected to grow in the next decade despite a high degree of exposure to AI. However, employment in other occupations, such as telemarketers, is projected to decline, which is more like what one might expect from an occupation with a high likelihood of automation (to both computerization and AI).

Future employment trends lack certainty

There is very little evidence of artificial intelligence taking away jobs on a large scale to date. Correlation between AI exposure and the projections of job growth or decline over the next decade remains low. Furthermore, just 10 years ago, our concerns about which jobs were at risk were quite different from the ones we are concerned about today, demonstrating that such considerations evolve. Many jobs once feared to be at risk did not end up showing major decline in employment data.

AI is such a rapidly changing field, we do not know much about its ability to one day have a large overall workforce impact, especially as current studies are mainly speculative. However, like the many technological changes that came before it, AI is a tool. Though rapid improvements in AI capabilities could lead to large workforce effects, over the next decade that worry can be tempered by the current data and the fact that concerns about technological unemployment are not new and rarely come to pass as first anticipated.

About the authors