Advances in AI will boost productivity, living standards over time

Artificial intelligence (AI), like many technologies before it, offers the potential to improve people’s living standards. Such advances can be approximated by changes in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita over time—the rate of change in the amount of output per person.

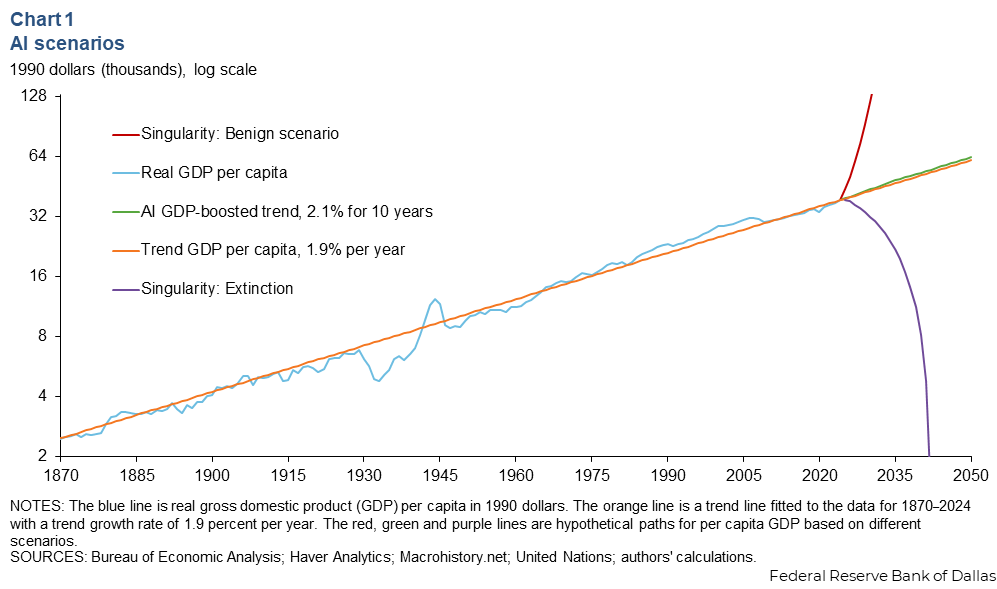

Chart 1 shows GDP per capita from 1870 to 2024 along with scenarios, some of them extreme, depicting what could happen to living standards between now and 2050.

As many other researchers have noted, what is remarkable over this 150-year-plus period is the relatively steady increase in living standards over time. Productivity growth is usually associated with both job destruction and job creation, although as we observed in a previous article, predicting the scale of these changes is challenging.

U.S. GDP per capita has advanced at an annual rate of approximately 1.9 percent a year, despite two world wars, the Great Depression, the Great Recession and major technological advances (such as electrification, the internal combustion engine and computerization) that were viewed as at least as important in their day as the advent of AI is today. Furthermore, the single most important determinant of this steady improvement has been productivity growth.

Under one view of the likely impact of AI, the future will look similar to the past, and AI is just the latest technology to come along that will keep living standards improving at their historical rate. With this expectation, living standards over the next quarter century will follow something close to the orange line in Chart 1, extending past 2024.

However, discussions about AI sometimes include more extreme scenarios associated with the concept of the technological singularity. Technological singularity refers to a scenario in which AI eventually surpasses human intelligence, leading to rapid and unpredictable changes to the economy and society. Under a benign version of this scenario, machines get smarter at a rapidly increasing rate, eventually gaining the ability to produce everything, leading to a world in which the fundamental economic problem, scarcity, is solved. Under this scenario, the future could look something like the (hypothetical) red line in Chart 1.

Under a less benign version of this scenario, machine intelligence overtakes human intelligence at some finite point in the near future, the machines become malevolent, and this eventually leads to human extinction. This is a recurring theme in science fiction, but scientists working in the field take it seriously enough to call for guidelines for AI development. Under this scenario, the future could look something like the (hypothetical) purple line in Chart 1.

Today there is little empirical evidence that would prompt us to put much weight on either of these extreme scenarios (although economists have explored the implications of each). A more reasonable scenario might be one in which AI boosts annual productivity growth by 0.3 percentage points for the next decade. This is at the low end of a range of estimates produced by economists at Goldman Sachs. Under this scenario, we are looking at a difference in GDP per capita in 2050 of only a few thousand dollars, which is not trivial but not earth shattering either. This scenario is illustrated with the green line in Chart 1.

Who is using AI, and what is it being used for?

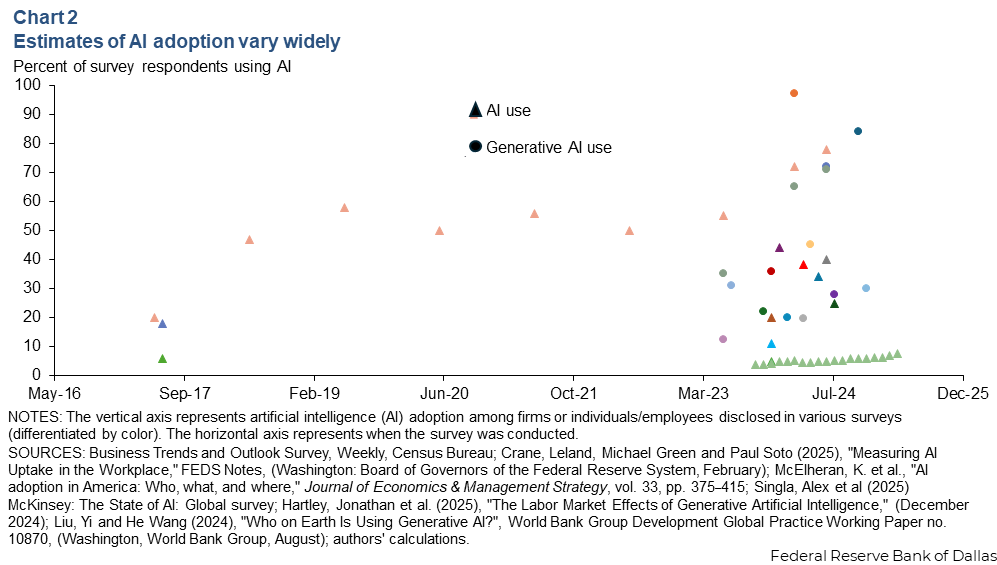

To get a sense of the potential of AI to raise productivity, it is important to ask how widely AI is being used and by whom. Surveys have come up with a wide range of estimates of AI use in firms, with most clustering between 10 to 50 percent and a clear upward trend in recent years (Chart 2 ).

The lack of consistency in survey findings about AI use can be attributed in part to differences in survey audiences and the wording of survey questions. Many surveys find that AI use skews male, young and highly educated. The most frequently documented examples of AI use are in coding and programming, translation, writing, editing and related tasks.

Most studies find that AI significantly boosts productivity. Some evidence suggests that access to AI increases productivity more for less experienced workers than for highly experienced ones. Perhaps this result reflects more experienced workers’ lack of need for external support because of their expertise.

Could AI help fix our productivity problems?

While many studies show AI adoption may provide a one-time boost to productivity, of potentially greater interest is whether AI adoption could boost the growth rate of productivity.

Economists at Goldman Sachs have suggested the adoption of AI could boost productivity growth by between 0.3 and 3.0 percentage points a year over the next decade (or rather, over the decade following its widespread adoption), with a median estimate of 1.5 percentage points. If realized, that would make a remarkable impact.

Productivity growth has been disappointing for most of the period since the Global Financial Crisis in 2007–09. Rapid productivity growth in the decades following World War II ended in the early 1970s and was followed by two decades of sluggish growth. Productivity boomed from the mid-1990s in part due to the information technology revolution. This faster growth ended around the time of the Global Financial Crisis, and productivity growth has been sluggish since, largely resembling what occurred from the 1970s to 1990s.

One strand of the literature attempting to explain recent disappointing data on productivity gains claims that new ideas became harder to find. In a 2020 paper, Nicholas Bloom and his coauthors document the declining productivity of researchers in a wide variety of areas. To the extent AI might lower the cost of idea discovery, it could help reverse this phenomenon.

Discovering new ideas with AI

Can AI speed up the discovery of new ideas and thereby boost the productivity growth rate, rather than just the level of productivity? There are a couple of pieces of intriguing evidence. In 2024, half of the Nobel Prize in chemistry was awarded to Demis Hassabis and John Jumper (both of Google DeepMind) for the development of an AI model for protein structure prediction. In February 2025 Google released AI co-scientist, an AI system intended “to help scientists generate novel hypotheses and research proposals” and more importantly “to accelerate the clock speed of scientific and biomedical discoveries.”

In addition, numerous media reports in recent years have mentioned companies using AI to perform tasks such as accelerating drug discovery and generating new antibodies to fight diseases. Such anecdotal reports support the idea that AI is helping with accelerated discovery and innovation.

While it is still early, there is evidence that advances in AI and its spread to all sectors of the economy could yield at least a persistent boost to the level of productivity, and perhaps even productivity growth, if AI accelerates the discovery of new ideas. If realized, AI will contribute in a very meaningful way to higher living standards.

About the authors