New Mexico marijuana legalization’s costs, benefits remain unclear

New Mexico legalized recreational marijuana use last year, joining 17 other states. The state has begun licensing for commercial cultivation and retail sales despite existing federal marijuana prohibitions.

Proponents laud the benefits of legalization—greater access to marijuana’s medicinal properties, a new source of tax revenue and job creation, and a decreased burden on law enforcement.

Critics argue legalization increases accessibility and use of marijuana, which are linked to adverse health effects, especially among chronic users. Anticipated benefits and costs partially offset one another, but there is considerable uncertainty around both.

Marijuana use and legalization are gaining acceptance. Nationally, the share of people age 12 or older reporting marijuana use rose from 11 percent in 2002 to nearly 18 percent in 2020.[1] New Mexico, at 18.7 percent, was near the national average in 2020, while Texas was below, at 12.5 percent. Those age 18 to 25 had the highest use rate, 34.5 percent, an increase of 4.7 percentage points since 2002.

Research on the health impacts of marijuana is limited and mixed.[2] Long term, heavy use is linked to increased risk of several mental health conditions and respiratory complications. Short term use may impair learning, memory and attention. Conversely, studies show marijuana is useful for treating symptoms accompanying chronic conditions such as pain, nausea, spasticity, convulsions, insomnia and post-traumatic stress disorder.

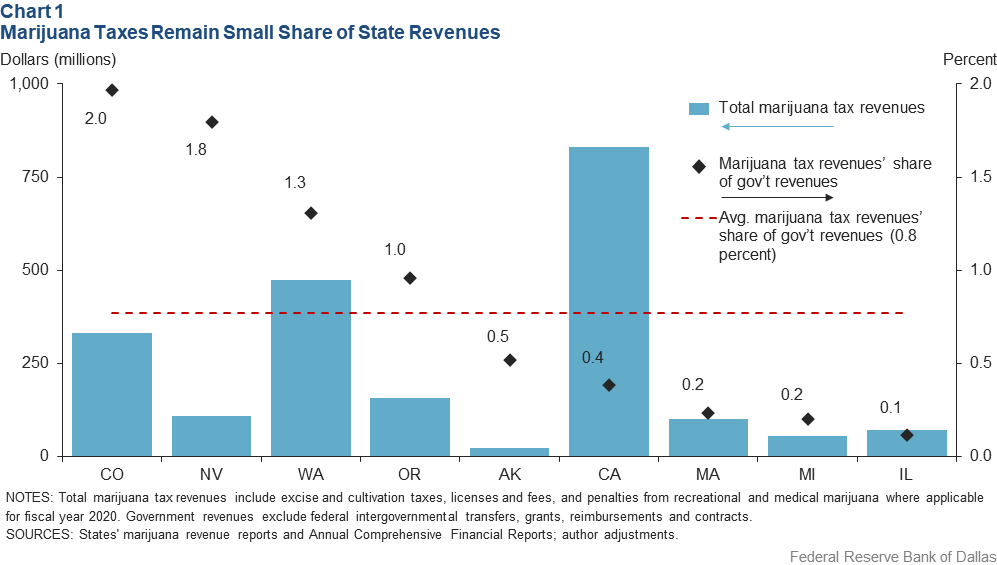

Supporters of marijuana legalization tout its economic benefits, including increased tax revenue. But states that have legalized and taxed recreational and/or medical marijuana earned on average just 0.8 percent of state revenues from it in 2020 (Chart 1). By comparison, sin taxes account for 2.8 percent of states’ tax collections.

While legalizing recreational marijuana may provide a small boost to New Mexico’s tax revenue, it will not materially change the state’s reliance on traditional industries, such as oil and gas. In addition, if consumers substitute marijuana for other taxed goods, realized revenues may fall short of projections. Marijuana tourism, meanwhile, could expand the consumer base and enhance tax revenues, benefiting the leisure and hospitality industry.

In setting marijuana tax rates, states try to meet several objectives. While higher prices can discourage use, they also risk pushing consumers into the black market. State tax regimes vary, and retail marijuana tax rates generally range from 10 to 21 percent. New Mexico specifies a 12 percent excise tax on recreational sales, with a 1-percentage-point increase annually beginning in July 2025 until reaching 18 percent in 2030.

Removing prohibitions on recreational marijuana sales will encourage investment in marijuana cultivation and retail outlets, creating jobs in construction, manufacturing and retail, as well as in ancillary industries such as professional and business services. A significant industry growth barrier, however, is its lack of access to banking services and credit due to the federal marijuana prohibition.

Some hope marijuana could become a substitute for harmful prescription drugs, playing a part in curbing New Mexico’s ongoing opioid epidemic. Ultimately, legalization is no panacea. Rather, it is an exercise in weighing costs and benefits and implementing an effective regulatory and public health oversight infrastructure.

Notes

- “2019 and 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health,” by the Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020.

- The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research, by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2017.

About the Authors

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: https://www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2022/swe2201.