District banks meet challenging times from position of strength

Texas banks confront an increasingly challenging operating environment, as the state’s usually strong economic growth is predicted to slow later this year and the Federal Reserve’s rapidly rising interest rate environment pressures banks’ deposits and profitability.

In recent months, attention nationally has focused on banks that invested in government securities. However, rapidly rising interest rates reduced the value of these holdings. (Generally, bond prices move inversely to yield.) Simultaneously, banks have raised the interest rates they pay on deposits to compete with each other and with money market mutual funds. Still, deposits have shifted from banks.

As a result, some banks are paying more in interest expense than they are earning on their securities holdings. The strong earnings of Eleventh District banks mean these losses are currently manageable, but until interest rates fall, these losses will be realized as lower earnings.

The failure of Silicon Valley Bank in California—the first bank to fail this year—has added to liquidity risks that could spill over into Texas banks and bring new regulations.

Dealing with Texas growth headwinds in 2023

The regional economy has been strong, though it is projected to slow this year. Texas real GDP growth (stripping out inflation) is expected to decline from 4.4 percent in 2022 to 1.5 percent in 2023, according to Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts projections. Softer energy prices and a potential U.S. recession present external headwinds.

Despite the last year’s challenges, banks in the Eleventh District—Texas, northern Louisiana and southern New Mexico—reported strong earnings and steady asset quality, while growing more slowly than the broader U.S. banking sector.

The Fed’s two main short-term policy rates rose sharply last year. The federal funds rate (the overnight bank borrowing rate) was 0.25 percent, and the prime rate (the interest rate banks charge to their most creditworthy customers) stood at 3.25 percent as banks entered 2022. The fed funds rate climbed to 4.5 percent and the prime rate to 7.5 percent by year-end.

This was the sharpest rise in short-term interest rates since then-Fed Chair Paul Volcker led a rate hike from 13.7 percent in October 1979 to 17.6 percent in April 1980.

Higher interest rates typically present more opportunity for bank profits in the form of higher net interest margins—net interest income divided by income-producing assets (generally loans and investment securities).

Banks in the region expanded lending rapidly in early 2022. Also, due to historically strong credit conditions, net new additions to loan loss reserves were low, even relative to banks nationally. Loan loss reserves are funds set aside by a bank to mitigate expected future losses on their loans. This suggests district banks did not need to loosen credit standards to grow their loan portfolios.

Meanwhile, banks that could not find enough lending opportunities instead bought securities such as Treasuries. When interest rates rise, the price of debt instruments such as Treasuries falls, and as interest rates rose substantially, many of these securities’ values fell below their purchase price.

Many banks entered 2023 with unrealized portfolio losses due to this interest rate risk, even when holding Treasuries, which in finance are regarded as safe assets.

Additionally, banks face high operating costs, notably, the cost of labor. District banks pay 56.7 percent of noninterest expenses for labor, compared with just 52.5 percent for U.S. banks. Moreover, bank efficiency ratios (noninterest expense as a percent of total revenues) had already improved to near long-term average levels at 58 percent for both area and U.S. banks, making a further decline unlikely.

Bank profitability steady

Bank revenues come from interest-generating activities such as making loans or holding bonds, or noninterest-generating activities such as providing letters of credit or debit card fees. Bank costs include interest paid on deposits and other liabilities, as well as overhead—items such as wages, rent, information technology and advertising.

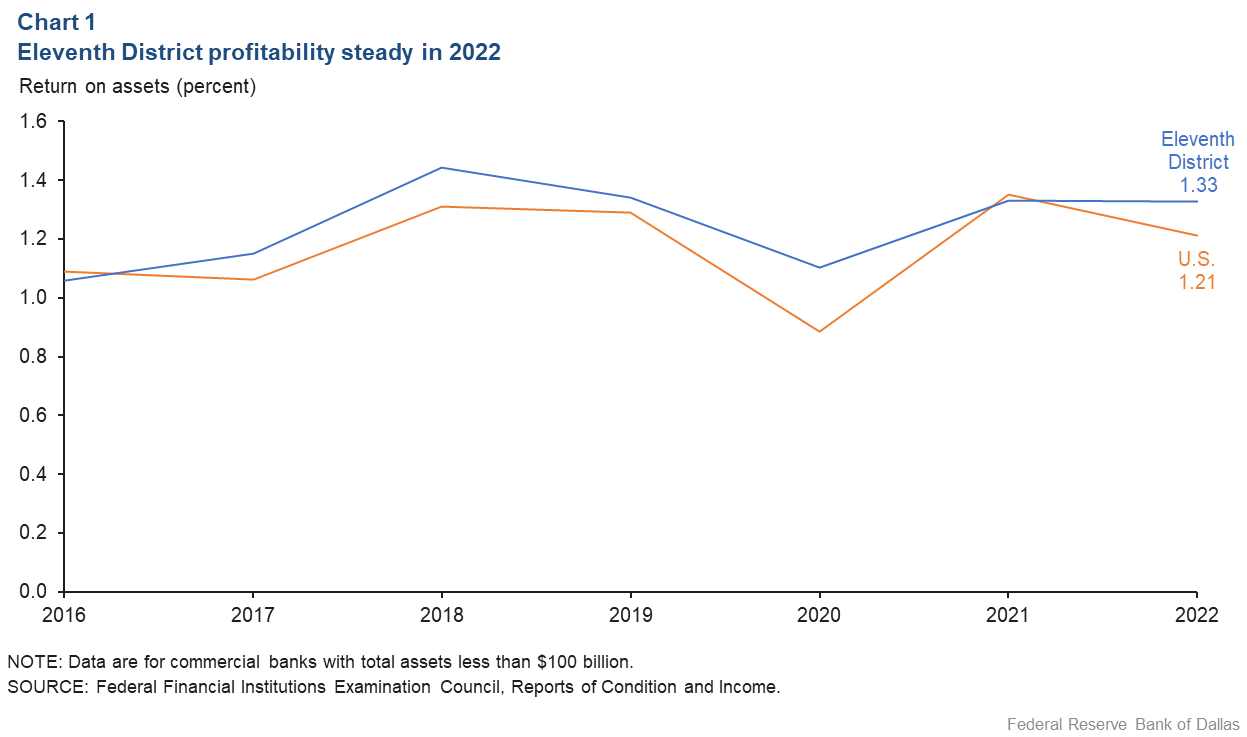

District banks typically earn greater profits than their national counterparts. Area bank profitability remained steady in 2022, with return on average assets (net income divided by average assets) holding steady at 1.33 percent, while nationally it declined to 1.21 percent (Chart 1).[1]

Substantially higher interest income drove profit growth locally and nationally, as interest income rose from 2.9 percent of average assets in 2021 to 3.3 percent in 2022 for area banks and from 3.2 percent to 3.7 percent for U.S. banks.

Local institutions set aside less money for loan loss provisioning than their national counterparts, allowing greater profitability despite lower interest income. District banks provisioned 0.09 percent of average assets in 2022, compared with 0.21 percent for U.S. banks. (Many banks took back funds in 2021 that they had set aside to cover anticipated pandemic-era losses that didn’t materialize.)

The district’s loan loss provisioning rate remains historically low, perhaps indicative of the banks’ stronger asset quality and better loan performance. The share of noncurrent loans (those behind in repayment) fell to 0.46 percent of all loans at year-end 2022, and the net charge-off rate (loans written off as a total loss) was just 0.07 percent. Nationally, the noncurrent share was 0.67 percent, and the net charge-off rate was 0.19 percent.

The provisioning rate is expected to rise this year, if nonperforming and charge-off rates move closer to the historical norms of 1.0 percent and 0.5 percent, respectively, likely damping bank profitability.

Containing expenses aids performance

Banks successfully contained interest expense and noninterest expense. Interest expense rose to only 0.41 percent of assets for area banks and 0.49 percent across the country, while noninterest expense was little changed at 2.18 percent in the district and 2.40 percent nationally.

Net interest margin—net interest income divided by earning assets—is another way to measure profitability. Net interest margin districtwide rose 24 basis points (0.24 percentage points) to 3.26 percent, though it remained relatively low. Nationally, it increased 29 basis points to 3.51 percent.

The district increase resulted from a 9.8 percent rise in loans and a 9.3 percent jump in securities holdings. Additionally, area banks cut reserve balances held at the Federal Reserve by 52.8 percent and boosted wholesale funding by 119.5 percent (Table 1). Wholesale funding refers to bank liabilities that are quick to arrange but are less stable than core deposits, such as federal funds, Federal Home Loan Bank advances and brokered deposits.

| Table 1: Loans and securities drive bank balance sheet growth | ||||

| Change: Dec. 31, 2021–Dec. 31, 2022 | ||||

| Eleventh District banks | U.S. banks | |||

| Dollars, billions | Percent | Dollars, billions | Percent | |

| Total assets | $4.7 | 0.7 | $146.2 | 2.2 |

| PPP | -$4.4 | -95.2 | -$53.1 | -89.1 |

| Loans (ex. PPP) | $32.4 | 9.8 | $517.7 | 12.8 |

| Securities | $17.2 | 9.3 | -$21.2 | -1.4 |

| Balances at Fed | -$40.1 | -52.8 | -$296.2 | -57.7 |

| Other assets | -$4.7 | -6.8 | -$54.2 | -8.0 |

| Total liabilities | $11.4 | 1.9 | $152.9 | 2.5 |

| Deposits | -$6.5 | -1.1 | -$60.6 | -1.1 |

| Wholesale funds | $12.7 | 119.5 | $175.3 | 97.6 |

| Other | $3.4 | 42.3 | -$440.9 | -8.7 |

| Equity capital | -$11.2 | -16.2 | -$60.0 | -8.1 |

| NOTE: Data are for commercial banks with total assets less than $100 billion. PPP refers to the Paycheck Protection Program. Equity capital equals total assets minus total liabilities. Other assets for a bank may include premises, accrued income, tax assets, equity investments without readily determinable fair values or intangible assets such as goodwill. Other liabilities may include accrued expenses, allowances for off-balance sheet exposures, deferred tax liabilities or other borrowed money such as mortgages the bank holds. SOURCE: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Reports of Condition and Income. |

||||

Nationally, loans increased 12.8 percent and securities holdings declined 1.4 percent, Fed balances fell 57.7 percent and wholesale funding increased 97.6 percent.

In other words, district banks moved their cash into higher-earning assets (loans and securities) and bought more earning assets by borrowing wholesale funds in the money market, while the broader U.S. banking sector moved its cash into loans but not securities.

For district banks that invested in relatively short-duration Treasuries or in loans with floating interest rates, this increase in net interest margin may be more sustainable than for banks that made long-dated, fixed-rate investments and are now experiencing higher deposit and wholesale funding costs.

Bank equity capital, deposits decline

Equity capital (common stock, paid-in capital, preferred equity, retained earnings and other comprehensive income) fell substantially in district institutions and less so nationally, despite banks’ profitability in 2022.

This largely resulted from the unrealized losses on banks’ available-for-sale securities positions, purchased when interest rates were low. Falling equity capital can spook large depositors who fear the institution’s capital may ultimately become “insufficient,” raising concern about the safety of accounts exceeding the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.’s deposit insurance limits.

Falling equity capital may also signal that a bank may be unable to continue paying dividends if it approaches regulatory minimum levels of equity and earnings weaken—during an economic downturn, for example.

Some bank securities are characterized as “available for sale” instead of “hold to maturity” in case the bank needs to raise cash before the holdings mature. Banks have more leniency in recognizing losses on their hold-to-maturity portfolios but face penalties if they use some of those securities for cash liquidity. District banks carried $15.9 billion (2.4 percent of total assets) of unrealized losses at the end of 2022, while nationally, banks held $132.2 billion (1.9 percent of assets) of unrealized losses.

Even when netted against their positive earnings, bank equity capital declined by 16.2 percent in the district and by 8.1 percent nationally. This trend created concern about the capitalization of some banks outside the district in March 2023—particularly driving bank runs at Silicon Valley Bank, Silvergate Bank and First Republic Bank, which prompted an emergency liquidity response program from the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Department of the Treasury. All three banks have closed.

As long as interest rates continue rising, unrealized losses from securities holdings will continue to weigh on bank capital despite healthy earnings.

Pandemic-era Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans have largely wound down, with the federal government largely forgiving these loans. Thus, the fee income from managing them, which had contributed to bank profitability, has disappeared.

Simultaneously, bank deposits have slowly declined year over year, dropping 1.1 percent both in the district and nationally from 2021 to 2022. Proceeds from PPP loans and pandemic-era government stimulus checks initially bolstered deposits before they were ultimately spent. A smaller part of the bank deposit decline was attributable to bank customers switching to higher-earning money market accounts in 2022—a trend that could accelerate if banks don’t raise their deposit rates.

District loan growth stays robust

Loans among district banks grew 9.81 percent in 2022 relative to 2021, while increasing 12.76 percent nationally (Chart 2).

The pandemic interrupted lending, a mainstay of most district banks. Demand for loans declined with the introduction of PPP and federal stimulus programs.

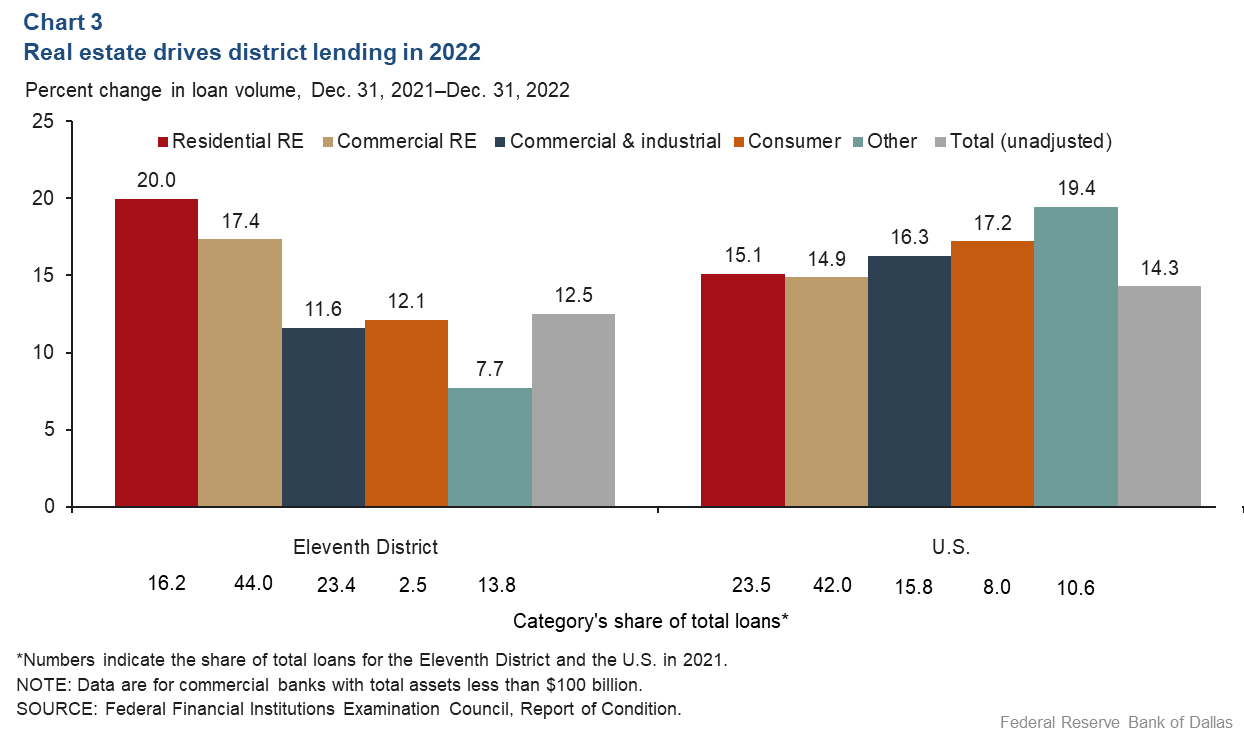

District loan growth was concentrated in real estate (both residential and commercial) last year, while commercial and industrial and consumer lending grew less rapidly (Chart 3).

This was true both in terms of year-over-year growth rates, as well as in absolute dollar amounts; residential and commercial real estate lending were the two largest growth categories at $9.38 billion and $19.55 billion growth, respectively.

Commercial and industrial lending includes loans to businesses—typically for shorter terms than real estate loans and at floating interest rates—with collateral other than real estate. Consumer lending provides financing for individual and household consumers, such as credit cards, personal loans and auto loans. Nationally, real estate loan growth grew approximately 15 percent annually in 2022, while consumer lending rose 17.2 percent year over year, and commercial and industrial lending was up 16.3 percent.

Loan quality remains little changed

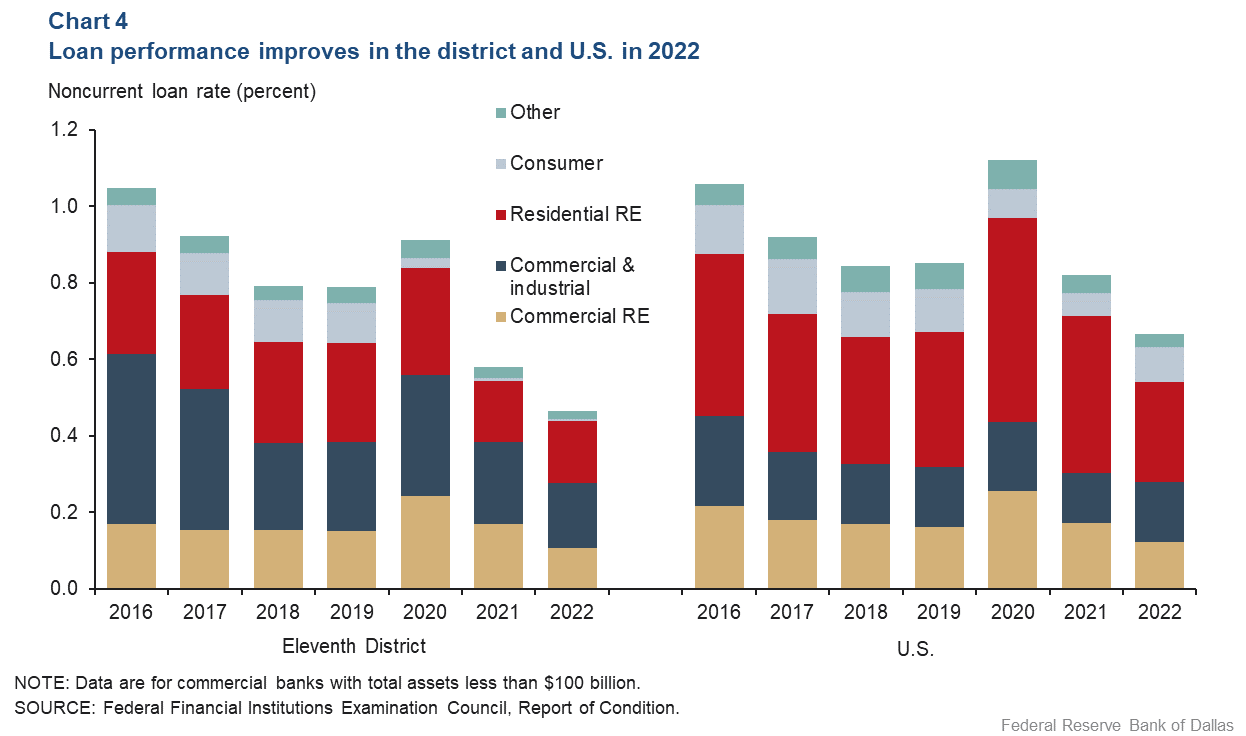

Loan performance continued to improve in 2022, with noncurrent loan rates falling in the district from an already-low 0.58 percent to 0.46 percent, and nationally from 0.85 percent to 0.67 percent (Chart 4). Noncurrent loans are loans 90-plus days past due. With noncurrent loan rates at a 20-year low, it is difficult to construct a scenario where rates do not increase, reverting toward historical averages. (For district banks, the average noncurrent loan rate since 2003 is 1.11 percent; the national average is 1.56 percent.)

With more companies offering remote work options since the pandemic, demand for office space and accompanying retail space has declined. As a result, some commercial real estate borrowers are unable to repay or refinance their loans. At the same time, residential rent growth has slowed markedly, and apartment vacancy rates are rising, possibly signaling mounting pressure on multifamily commercial real estate borrowers.

Average noncurrent commercial real estate loan rates were at a historically low 0.24 percent for all district banks (0.29 percent nationally) at year-end 2022. However, periods of high loan origination and a concentration in commercial real estate have been historically associated with increasing credit risk during a downturn—noncurrent loan rates can rise by a factor of 20 to 30 during a recession. Indeed, during the 2008 recession, the noncurrent rate peaked at 4.67 percent for district banks and rose to 6.34 percent nationally.

Across all other loan categories, noncurrent loan rates also did not increase for district banks in 2022. However, nationally, the noncurrent loan rate for commercial and industrial ticked up from 0.8 percent to 0.9 percent and, for consumer loans, from 0.6 to 1.0 percent.

Of the major loan categories, commercial real estate and commercial and industrial loans improved the most in the district, while nationally, a better performance for residential real estate and commercial real estate more than offset a small deterioration in commercial and industrial and consumer loans.

Increasing equity could aid banking outlook

District banks entered 2023 with strong profitability and loan quality. Yet vulnerabilities had already developed as interest rates rose, deposits fell and the value of banks’ securities holdings declined. Additionally, some institutions relied on less-stable funding sources such as uninsured deposits.

In early March 2023, concerns about unrealized losses on banks’ bond holdings precipitated a classic bank run by large uninsured depositors of some regional banks, most notably Silicon Valley Bank. To forestall a broader crisis, the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department announced an emergency Bank Term Funding Program to provide liquidity to troubled banks.

Banks holding Treasuries and other government-backed debt before the early March turmoil can pledge those bonds at their face value (often substantially higher than their current market value) to borrow for up to one year from the Fed. While the extraordinary move (exercised under the Federal Reserve’s authority to intervene in periods of systemic crisis) has stabilized bank deposits, some banks remained under pressure due to concerns about their unrealized losses.

These unrealized losses from higher rates could dissipate if inflation falls and the Fed lowers interest rates. However, that scenario may require an economic downturn, which would then pressure asset quality and banks’ loan positions. The most straightforward way for banks to navigate this crisis may therefore be to increase equity on the strength of their earnings.

Note

About the author

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.