After the bust, the long road to housing finance reform

One of the most dramatic events of the 2007–08 financial crisis was the imposition of federal conservatorships at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) that remain central to the U.S. housing finance system. At the time, U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry “Hank” Paulson stated that “policymakers must view this next period as a ‘timeout’ where we have stabilized the GSEs while we decide their future role and structure.”

That timeout period has lasted more than 11 years.

The Treasury recently released a plan proposing several administrative and legislative changes aimed at returning Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to the private sector. Understanding steps taken by the federal government in 2008 to rescue the two GSEs is useful when considering challenges involving the transition.

Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac’s mortgage role

Fannie Mae, whose actual name is the Federal National Mortgage Association, and Freddie Mac, whose actual name is the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp., serve a central role in the U.S. housing finance system and collectively hold or guarantee almost one-half of all outstanding home mortgage debt.

Both GSEs are public companies created by Congress to enhance the liquidity and stability of the U.S. secondary mortgage market, where investors buy and sell pools of mortgages. Lawmakers also intended that the GSEs promote access to mortgage credit, particularly among low- and moderate-income households and neighborhoods.

To achieve this mission, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac engage in two principal activities: one, creating “agency” mortgage-backed securities by insuring mortgage pools against credit losses; and two, investing directly in mortgage assets.

The two GSEs’ federal charters provide important competitive advantages against other institutions financing mortgages, and investors had long assumed U.S. taxpayer support of their obligations. As publicly traded firms, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac leveraged the funding advantages of this implied guarantee to become very large, profitable and politically powerful.

GSEs falter during the housing collapse

As the housing crisis intensified during 2008, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac became financially distressed. In the face of a large nationwide decline in home prices and the associated spike in mortgage defaults, the GSEs’ concentrated exposure to U.S. residential mortgages, coupled with their high leverage, was a recipe for disaster.

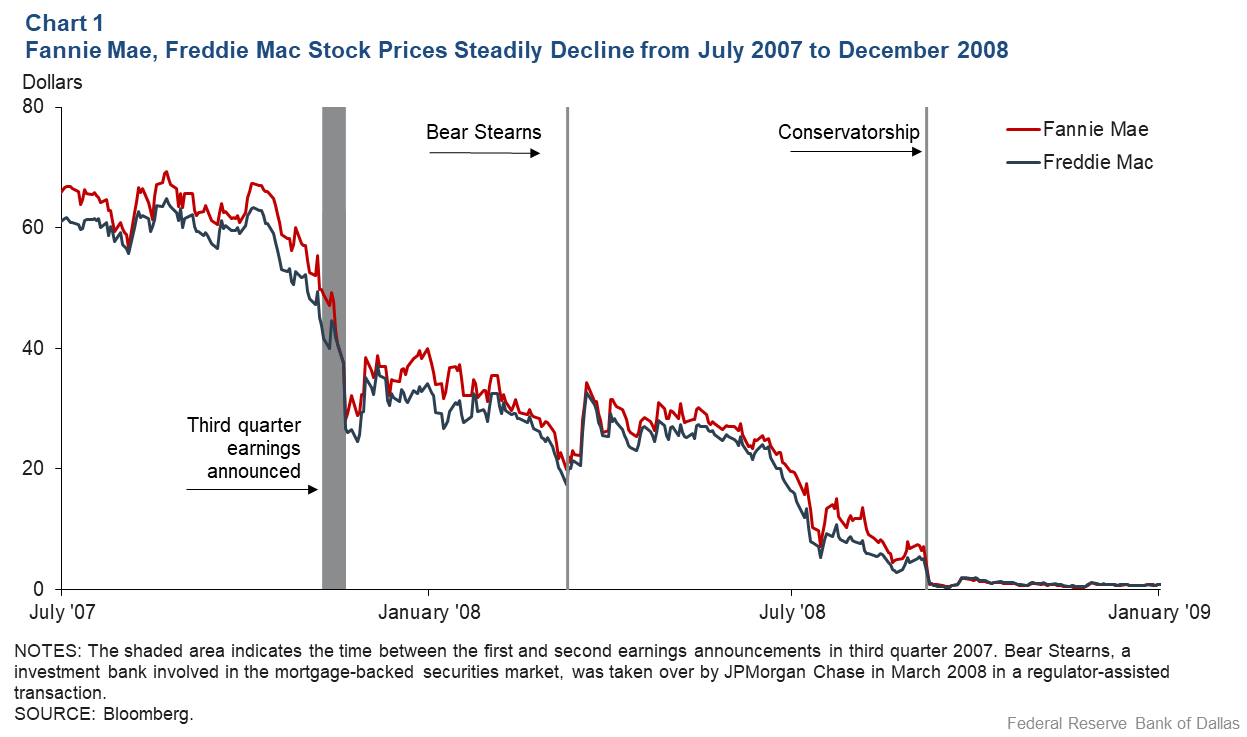

The share prices of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the year before federal intervention steadily slid lower (Chart 1). Their prices first dropped sharply during fall 2007 after both GSEs reported third-quarter losses and rallied briefly in mid-March following JPMorgan Chase’s takeover of the investment firm Bear Stearns. The share prices fell further from the $25–$30 level in April 2008 to below $10 in mid-July. Debt investors during this time also increasingly sought clarity from the federal government about whether bondholders would be shielded from losses.

The federal government initially responded in July 2008 by passing the Housing and Economic Recovery Act (HERA), which (among its many provisions) gave the U.S. Treasury unlimited emergency investment authority in the two institutions through 2009. Less than two months after HERA’s passage, the GSEs’ newly created federal regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), placed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac into conservatorship.

Terms of the federal intervention

FHFA took control of the two institutions in an effort to conserve their value and curtail any financial contagion. Concurrently, the Treasury exercised new emergency authorities and entered into senior preferred stock purchase agreements with each institution to ensure they maintained a positive net worth.

Each senior preferred stock agreement was initially for an indefinite term and for up to $100 billion. For investors in GSE debt and mortgage-backed securities, the Treasury support meant that the “implied” federal guarantee had become an “effective” one.

The senior preferred stock purchase agreements called for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to provide the Treasury with four claims. They were:

- $1 billion of senior preferred shares (that were “senior” to existing common and preferred stock).

- A 10 percent dividend on all senior preferred shares.

- Warrants allowing the purchase of common stock representing 79.9 percent of each institution on a fully diluted basis.

- A quarterly commitment fee to be determined by the Treasury and the FHFA in consultation with the Federal Reserve. (To date, the Treasury has not exercised the warrants to purchase common stock or charged a commitment fee.)

The senior preferred stock purchase agreements also required Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to substantially reduce their retained investment portfolios, which at a combined $1.5 trillion posed a systemic risk to the financial system and were viewed by policymakers as not central to the GSEs’ core mission.

Amending terms of the GSE rescue

There have been three subsequent amendments to the preferred stock purchase agreements. The first, in May 2009, raised the maximum federal commitment to each GSE from $100 billion to $200 billion. A second amendment came soon after, in December 2009, and provided unlimited support to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac through 2012.

The two amendments reflected increasing GSE losses during 2009 and HERA’s authorization of Treasury investment only through the end of that year. A third amendment to the senior preferred stock purchase agreement announced in August 2012 replaced the 10 percent dividend on the Treasury’s senior preferred stock with a “full income sweep”—all Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac profits would be remitted to the Treasury.

One intention of this third amendment was to end the circular practice of the GSEs’ borrowing from the Treasury in order to pay the Treasury its preferred stock dividends. More generally, the policy was also consistent with the Obama administration’s 2011 commitment to wind down Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—that is, not to allow the two institutions to retain profits, rebuild capital and return to the market in their prior form. A change in administrations from Obama to Trump altered the GSEs’ fate—from a road to liquidation to instead, recapitalization.

Anticipated re-emergence of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac

The imposition of conservatorships at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in September 2008 was one of the most dramatic events of the financial crisis. In the absence of a legislative solution after 11 years, the Trump administration recently proposed returning them to private control after recapitalization.

The anticipated transition process will boost required minimum capital requirements for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—after the former levels proved inadequate during the housing bust—and will include steps that ease Treasury involvement in the GSEs.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.