The production process drives fluctuations in output and uncertainty

Economic uncertainty varies over time, especially during recessions. Recent research has focused on how changes in uncertainty affect economic activity. Yet, it is mostly silent on the converse—how changes in economic conditions can affect uncertainty—which our research finds is of greater importance.

This distinction is important because many studies have found that uncertainty has a large impact on economic activity. If economic developments drive most of the changes in uncertainty—rather than the reverse—then the direct effect of a change in uncertainty on economic activity is much smaller than previous research has shown.

Prior research has also focused on the impact of infrequent events—wars and financial crises—on uncertainty. Those sources, however, do not explain why uncertainty might vary in normal times.

This post, based on our recent research, instead explores the relationship between inputs in the production process as a source of variation in uncertainty. Production inputs are often classified as either capital or labor. Capital represents things such as the machines and buildings used in production, while labor represents hours worked.

Importance of complementarity

Theoretical models of an economy often include a production function, which is an equation that describes how much output firms will produce given the inputs: capital, labor and their productivity. The function reflects the common-sense idea that firms can produce more when the inputs are in greater supply or become more productive.

What influences how much extra output is generated from an increase in productivity? If capital and labor are complements, changes in the supply or productivity of one of those inputs would also affect the productivity of the other input—a phenomenon we refer to as a spillover. In turn, this relationship influences how much extra output is produced by having more of one input while the other is fixed.

There is considerable empirical evidence supporting a strong degree of complementarity. Production functions that take this into account suggest the size of spillovers depends on the relative abundance of the inputs. As a result, in some scenarios, output will respond more when one input becomes more plentiful, while in others, output responds less.

Perhaps surprisingly, the most commonly used production function in business-cycle and monetary policy research assumes a degree of complementarity that implies the spillover effects are always the same, regardless of the relative abundance of the inputs. As a result, the extra output produced from adding labor is always the same.

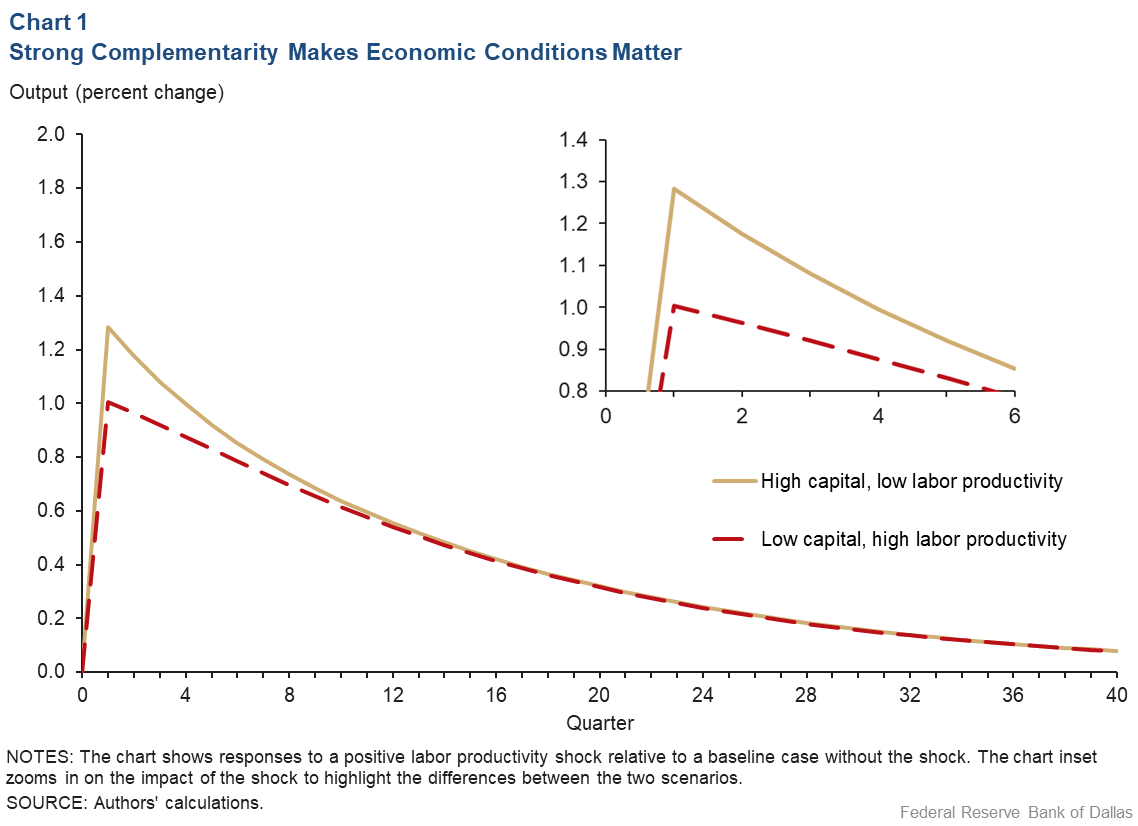

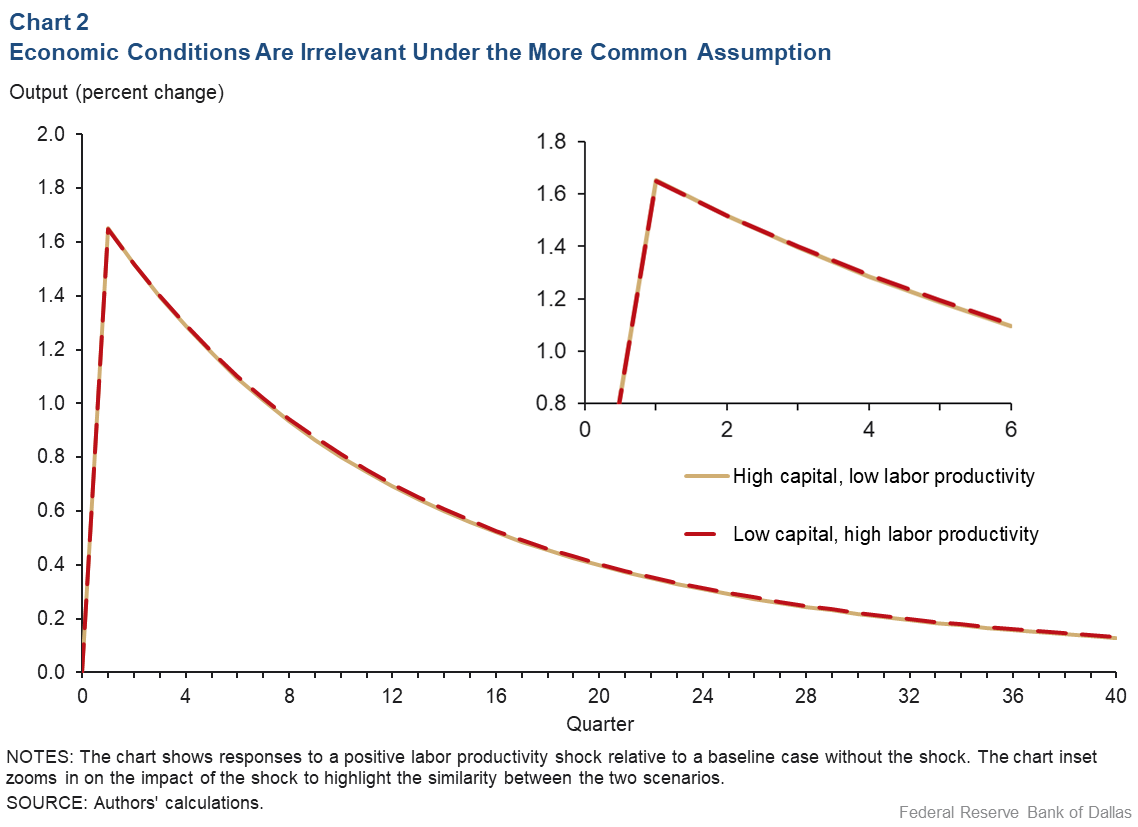

Charts 1 and 2 illustrate this mechanism using a theoretical model. Each chart plots the response of output to an increase in labor productivity.

Chart 1 shows the responses when capital and labor are strong complements, while Chart 2 shows the responses under the more common assumption that capital and labor are not complements. Both consider two scenarios—one where capital is relatively abundant (beige line) and another where capital is relatively scarce (red dashed line).

There are two important results. First, the response of output is smaller when inputs are strong complements (Chart 1) than under the common assumption (Chart 2). Since capital does not immediately adjust in response to the increase in labor productivity, additional labor is not as useful in production when the inputs are strong complements. This leads to a smaller increase in labor demand and therefore a smaller output response.

Second, in Chart 1, the response of output depends on the initial level of inputs. Output increases more when capital is relatively abundant (beige line) than when capital is relatively scarce (red dashed line). When capital is scarce, complementarity prevents firms from taking full advantage of the increase in labor productivity. In Chart 2, output responds the same regardless of the state of the economy.

Economic changes generate fluctuating uncertainty

How does this mechanism translate into uncertainty? Uncertainty is measured by the expected volatility of output growth. To better understand this statistic, suppose people are asked to predict how much the economy will grow next quarter. They would make use of available information and come up with their best estimate. However, each person would face uncertainty about what will actually occur.

For example, if the most likely growth rate is 2 percent, someone who is fairly confident might predict output growth between 1.5 percent and 2.5 percent, while someone who is more uncertain might say 1 percent to 3 percent. A wider range means greater uncertainty and implies a higher expected volatility of output growth.

The results from Chart 1 demonstrate that when capital and labor are complements, output responds differently depending on current economic conditions. The differences in the responses imply that forecasts for output growth—and hence the level of uncertainty—also depend on what is happening in the economy.

Suppose the economy is initially in a boom where capital is relatively abundant, and then a large decline in labor productivity occurs at the onset of a recession. In that case, the response of output is elevated and uncertainty is high. At the end of a recession, suppose capital is relatively scarce and that an increase in labor productivity marks the beginning of an expansion. Since capital is scarce, the changes in output are smaller and future outcomes are relatively more certain. Thus, uncertainty will countercyclically vary across time in relation to output growth, and business-cycle turning points will exhibit the most extreme levels of uncertainty.

Key economic takeaway

When capital and labor are complements in production, changes in productivity can lead to empirically meaningful changes in uncertainty over time, as we show in our related research paper. This suggests that a sizable portion of the fluctuation in uncertainty is driven by what is happening in the economy, while uncertainty, by itself, most likely has a smaller impact on the economy than previously thought.