Don’t Look to the 2013 Tantrum for the Effect of Tapering on Emerging Markets

Emerging-market volatility evidenced during the “taper tantrum” of 2013 arose because of low reserves and high foreign currency debt among emerging economies. Since 2013, many of them have improved their external balance sheets and would be much less vulnerable to Federal Reserve tapering today.

In May 2013, then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke first suggested that the Fed would begin reducing its program of asset purchases—Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities—commonly referred to as quantitative easing, or QE3, as a means of supporting the U.S. economy. That set off a market reaction—the taper tantrum—affecting the U.S. and nations abroad.

It led to higher interest rates and mortgage rates in the U.S. and falling capital inflows and balance of payment pressures elsewhere in the world, particularly in emerging markets.

Emerging markets and the 'taper tantrum' of 2013

Most emerging-market countries can’t borrow abroad in their own currency. When a country runs a trade deficit, it needs to borrow in U.S. dollars to cover that deficit. Over time, this leads to a stock of foreign currency-denominated debt. The country needs a steady stream of dollar financing to finance current deficits and to service and roll over any dollar-denominated debt.

Federal Reserve tightening, or even the expectation of tightening, complicates this dollar financing, as investors reallocate their holdings to now higher-yielding U.S. assets. This leads to currency depreciation in the debtor countries and rising instability due to an increase in the real (inflation-adjusted) value of foreign currency-denominated debt. Sometimes, local central banks feel compelled to “follow the Fed” and raise interest rates to entice capital to return.

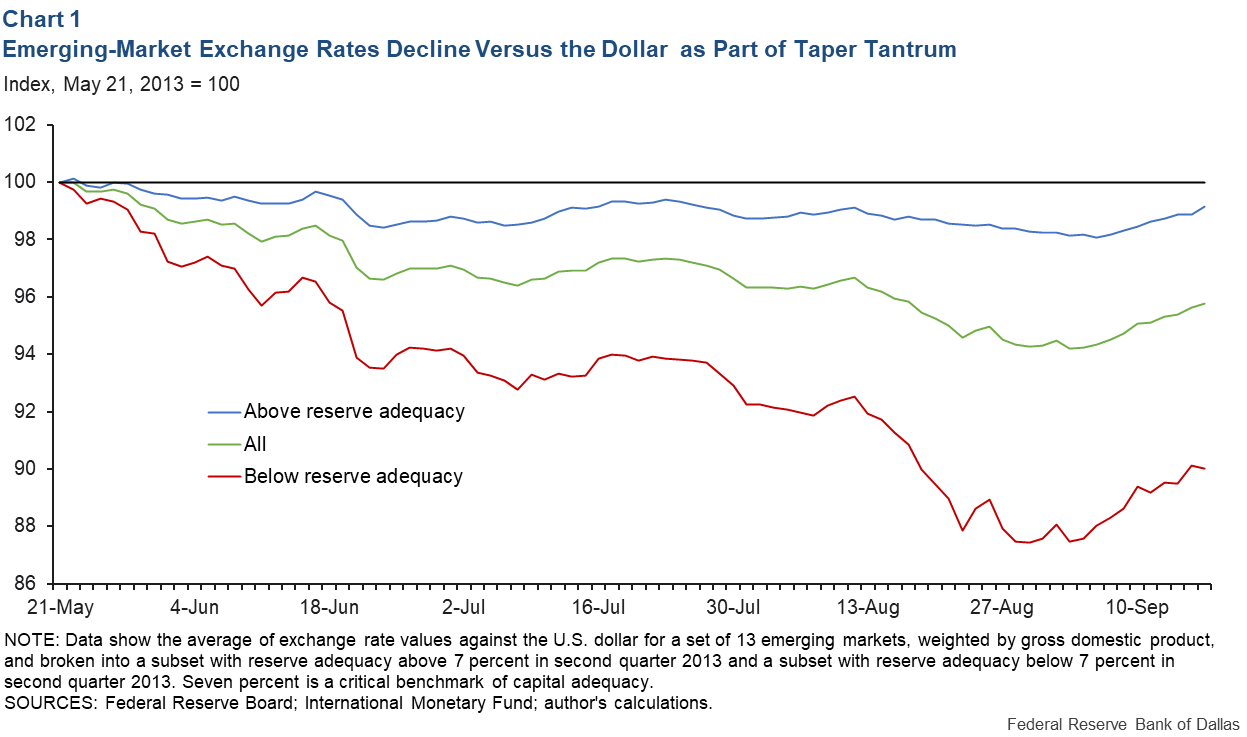

Chart 1 plots the average of the exchange rate against the U.S. dollar for a set of 13 large emerging-market countries, weighted by gross domestic product, in the months after Bernanke’s first mention of tapering on May 22, 2013. The green line is the average path of the exchange rate across all 13 countries.

In the four months after Bernanke first mentioned tapering, emerging-market exchange rates fell by 6 percent against the dollar.

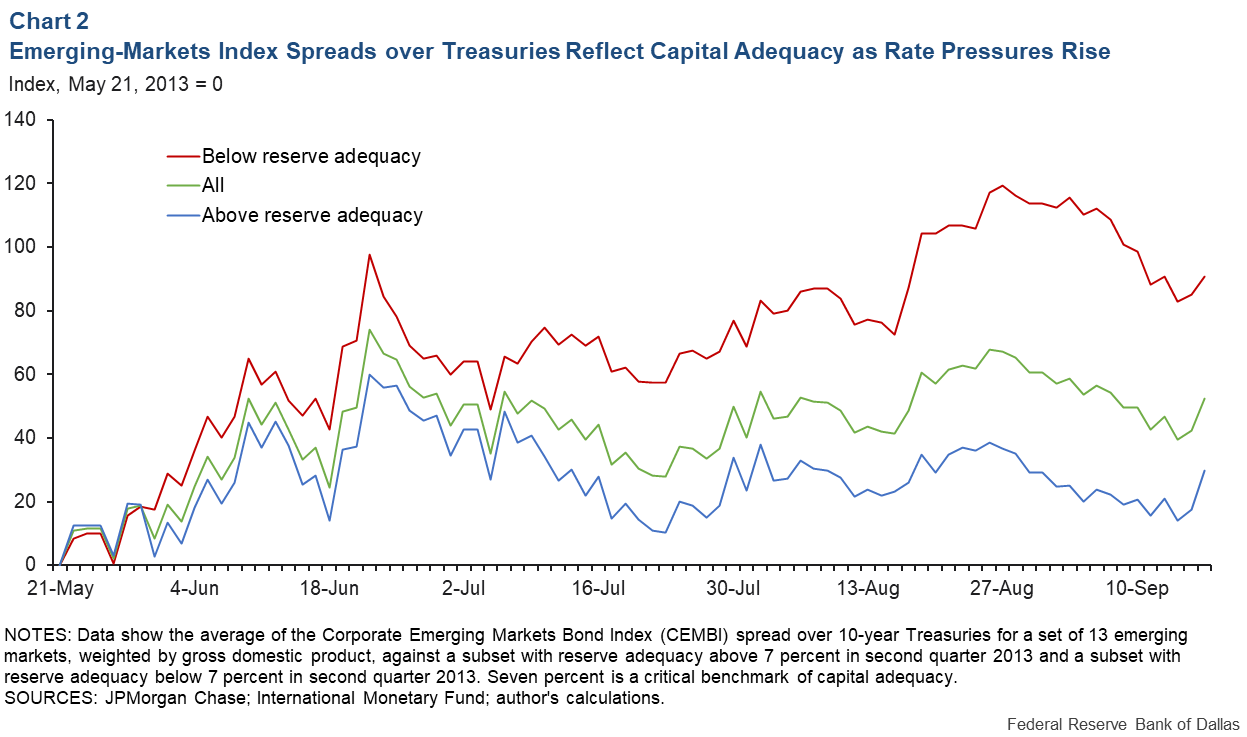

JP Morgan’s Corporate Emerging Market Bond Index (CEMBI) for the same set of countries measured against the yield on the 10-year Treasury provides additional insight. The CEMBI measures the average yield on a country’s corporate-investment-grade dollar-denominated bonds; the spread above Treasuries measures risk relative to safe U.S government returns. In the four months after the first suggestion of tapering, this spread rose by an average of 60 basis points (0.6 percentage points) (Chart 2).

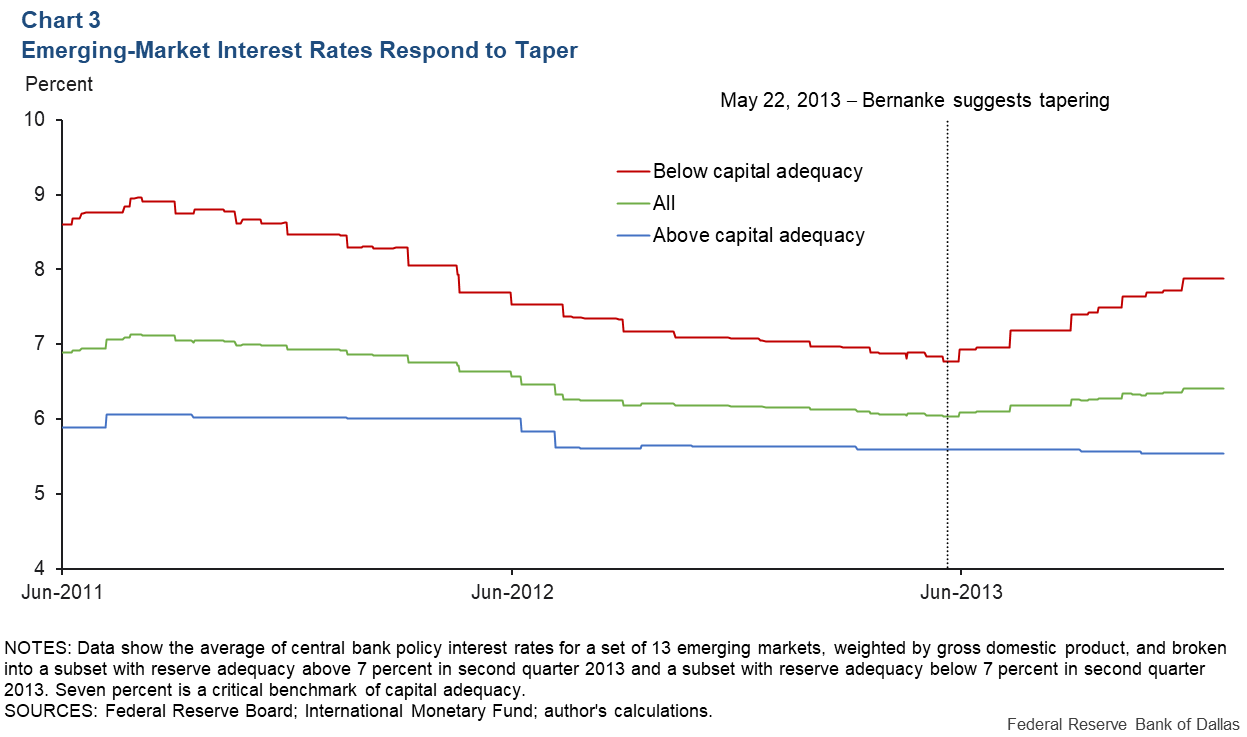

Additionally, the suggestion of tapering and the resulting shift in capital flows forced many emerging-market central banks to “follow the Fed” and tighten monetary policy. Chart 3 presents the average central bank policy rate for the same set of countries, taking a longer time-series perspective in order to highlight that the suggestion of tapering led to the end of a nearly two-year period of policy easing among emerging-market central banks.

Central bank reserves guard against instability

To guard against instability arising from shifting capital flows, central banks in emerging-market economies hold reserves—liquid, foreign-currency-denominated assets. These reserves provide foreign-currency liquidity to domestic borrowers at times when it is hard to obtain it from foreign lenders, thus enabling domestic borrowers to finance current deficits and roll over maturing debt.

Emerging markets must decide what reserve level is adequate to protect their currency against swings in foreign monetary policy. Pablo Guidotti, a former deputy finance minister in Argentina, reached a conclusion about the appropriate level that former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan later popularized. In a 1999 speech to the World Bank, Greenspan summarized the rule, stating “that countries should manage their external assets and liabilities in such a way that they are always able to live without new foreign borrowing for up to one year.”

The Guidotti-Greenspan rule leads to a simple measure of a central bank’s reserve adequacy: foreign- exchange reserves minus the sum of short-term foreign-currency-denominated external debt and the current account deficit. The current account is the net value of exports and imports of goods and services and international transfers of capital.

In a 2018 Dallas Fed Economic Letter, two co-authors and I used a panel data regression to test how a country’s reserve adequacy affects the sensitivity of a country’s CEMBI spread to changes in the federal funds futures rate (a measure of anticipated movement in the U.S. policy rate).

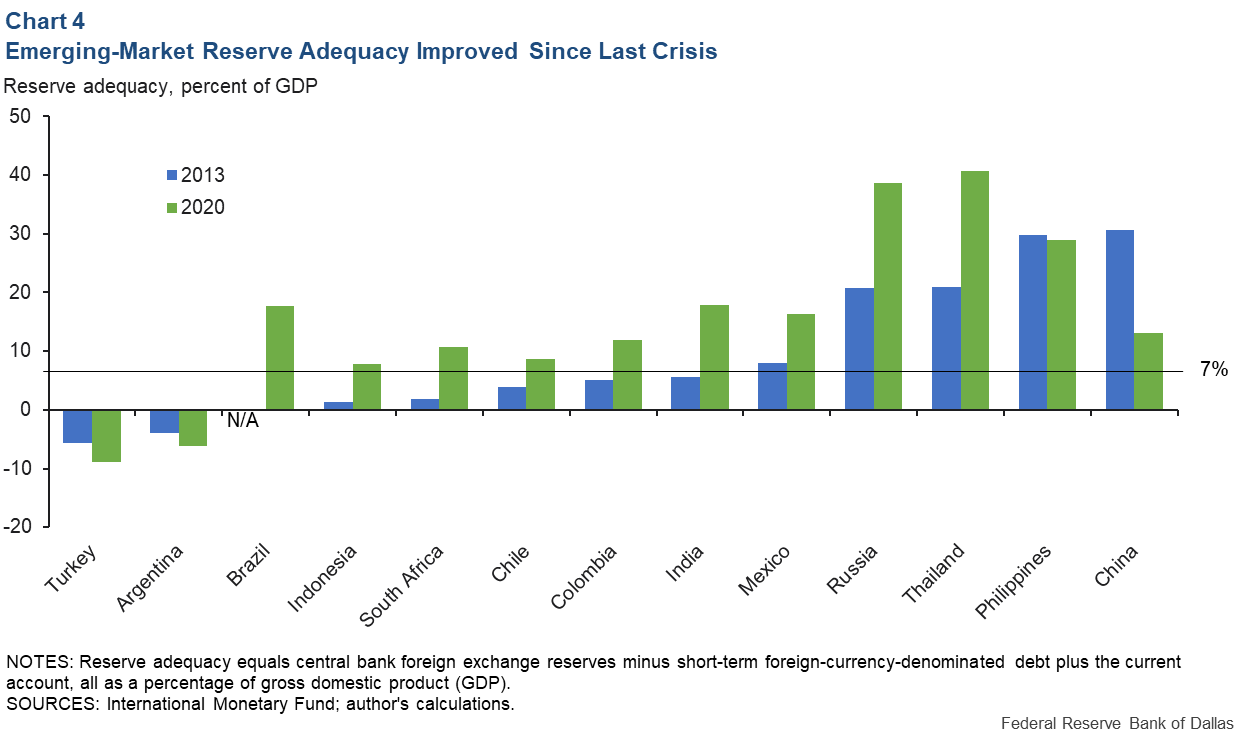

Allowing a breakpoint in the regression, we find that a critical value for a country’s reserve adequacy is 7 percent. When reserve adequacy is less than that, the sensitivity of a country’s CEMBI spread to changes in the fed funds futures is proportional to a country’s reserve adequacy. Reserve adequacy above 7 percent doesn’t much affect CEMBI spread sensitivity to the expectations of U.S. monetary policy.

Chart 4 presents the level of reserve adequacy in each of 13 major emerging markets, both in the second quarter of 2013 and in the latest data release—fourth quarter 2020. The chart also depicts the 7 percent cutoff. At the time of the taper tantrum in 2013, at least seven of these 13 major emerging markets’ reserve adequacy missed this cutoff. Among them were particularly volatile economies that during the taper tantrum were grouped as the “Fragile Five”—Brazil, India, Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa.

The red line in Charts 1, 2 and 3 presents the average across all 13 countries with reserve adequacy below 7 percent in 2013; the blue line presents the average across the countries with reserve adequacy above 7 percent. Between May and September 2013 there was 2 percent currency depreciation in the countries with high reserve adequacy but nearly 15 percent depreciation in countries with low reserve adequacy.

Over the same period, the CEMBI spread rose by 40 basis points in countries with high reserve adequacy but by 120 basis points in countries with low reserve adequacy. After the first mention of tapering in May, central banks in countries with high reserve adequacy did not raise their policy interest rate, but central banks in countries with low reserve adequacy raised rates by more than 100 basis points by the end of 2013.

Lessons from 2013 applied today

Just two countries, Turkey and Argentina, are in the low reserve adequacy category today; both were at the bottom in 2013. Four of the members of the original Fragile Five were above the 7 percent threshold as of year-end 2020. These emerging markets have higher central bank reserves, lower foreign-currency debt and smaller current account deficits.

This suggests that emerging-market balance sheets are in much better shape now than they were during the taper tantrum of 2013.

About the Author

J. Scott Davis

Davis is a senior research economist and advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.