Federal aid helps border keep pace with Texas economy during pandemic turmoil

Communities along the Texas–U.S. border suffered a series of economic blows beginning with the arrival of COVID-19 in March 2020. The challenges included elevated infection and fatality rates, a shutdown of ports of entry and a trade collapse.

However, subsequent U.S. pandemic relief policies boosted the border economy, helping it keep pace with state growth. The restoration of trade with Mexico and a surprise migration surge also supported more-recent border economic activity.

A Heavy Toll on Activity

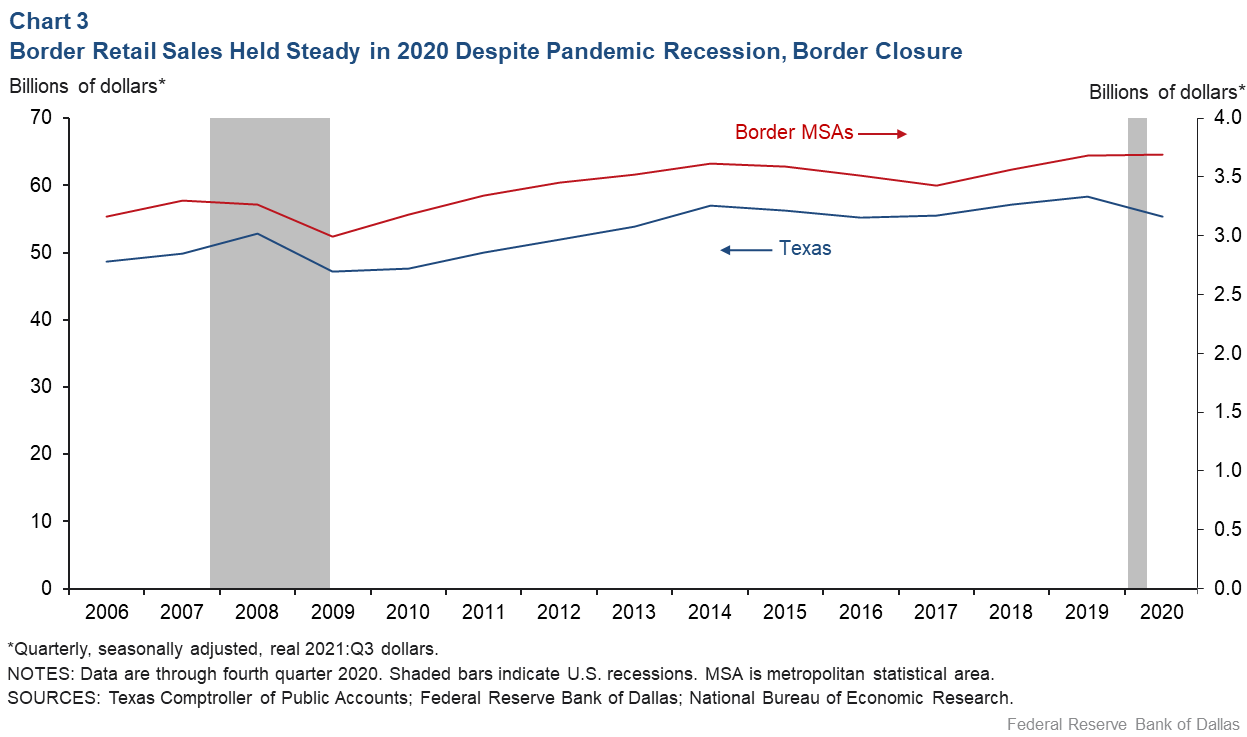

The Texas border economy heavily depends on processing international trade with Mexico—valued at about $350 billion per year—as well as on Mexican citizens crossing daily to shop and work in the U.S. In a typical year, about 30 percent of border retail sales are to Mexican shoppers. Once the pandemic struck and COVID-19 spread to the area, the border was closed to nonessential traffic and trade, and tourism plummeted.

During the initial COVID-19 waves in Texas through fall 2020, the border infection rate was about twice that of the state. Hospitalization and death rates also exceeded state levels.

Given these challenges, it would not have been surprising to see the border economy grind to a halt. Beside navigating trade and border-crossing disruptions, the border confronted the pandemic’s negative impact on its outsized service sector and the difficulty of shifting to a work-from-home regimen as many professional and office workers elsewhere had done.

Nevertheless, the border economy has emerged from the difficult days and is doing well almost two years after the arrival of COVID-19.

Federal COVID-19 Aid Cushions Economic Impact

The main reason behind the border economy’s surprisingly good performance has been an array of federal relief programs, notably the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act; the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021; and the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

Texas received almost $322 billion from federal sources through January 2022, second to California at $555 billion, according to Peter G. Peterson Foundation calculations. The amount of the aid per recipient—notably, stimulus payments and supplemental federal unemployment benefits—didn’t vary by location. This meant that families in low-income areas, such as the Texas–Mexico border, received much higher transfers as a percentage of their income.

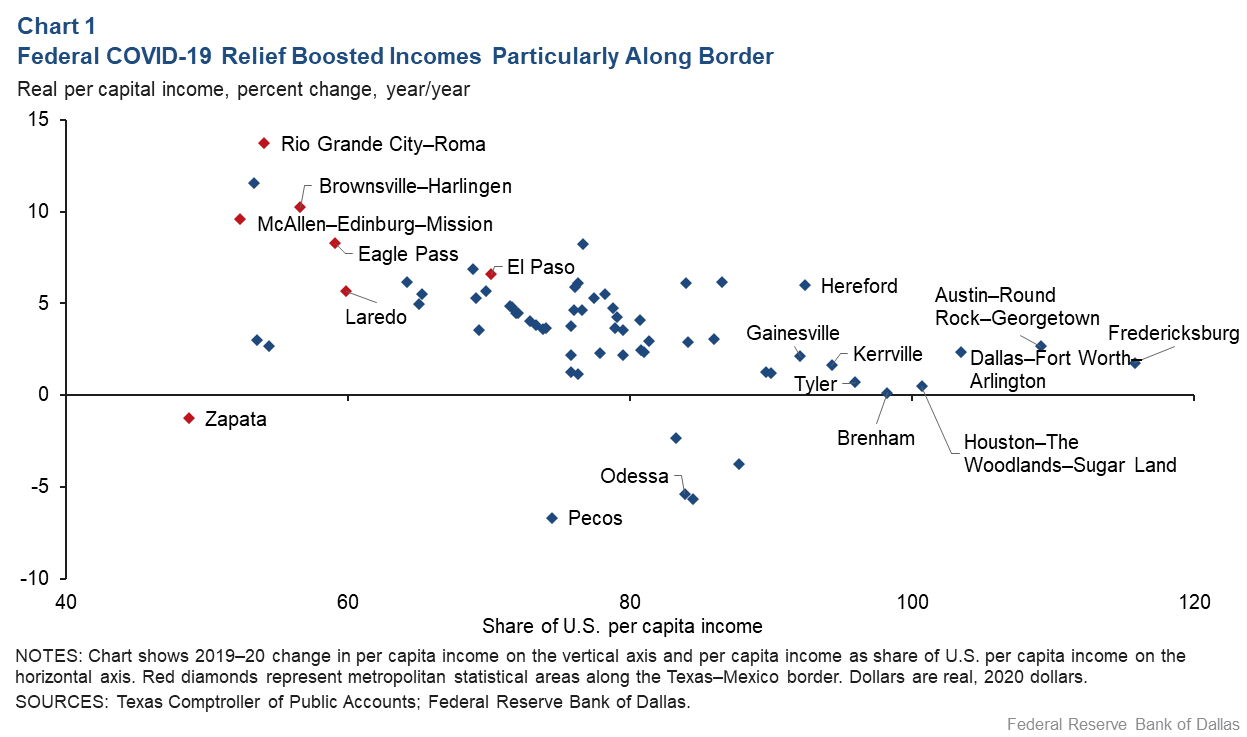

Chart 1 depicts Texas metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) by the change in inflation-adjusted per capita income from 2019 to 2020 (vertical axis) and MSA per capita income as a share of the U.S. national average (horizontal axis). The 10 poorest MSAs—of which six are on the border—have per capita income that averages 56 percent of the national level. During 2019–20, their average inflation-adjusted per capita income increased 6.9 percent.

In the top 10 MSAs—where per capita income is well above the national average—per capita income increased just 0.8 percent. By comparison, income declined mostly in MSAs with large exposure to oil and gas production such as Midland and Odessa in the Permian Basin, a sector that suffered greatly at the beginning of the pandemic.

Along the border, the supplemental federal unemployment benefit of $600 per week had a significantly larger impact than in Texas overall. Unemployment benefits vary from state to state, averaging $385 per week nationwide in January 2020. Adding the $600 supplement included in the CARES Act brought average weekly unemployment benefits to $985.

The border average weekly wage was $609 in 2019, so expanded unemployment benefits represented a 62 percent raise above typical border wages. Statewide was not as favorable to workers; the average weekly wage was $1,150, which exceeded the expanded unemployment benefit by 17 percent.

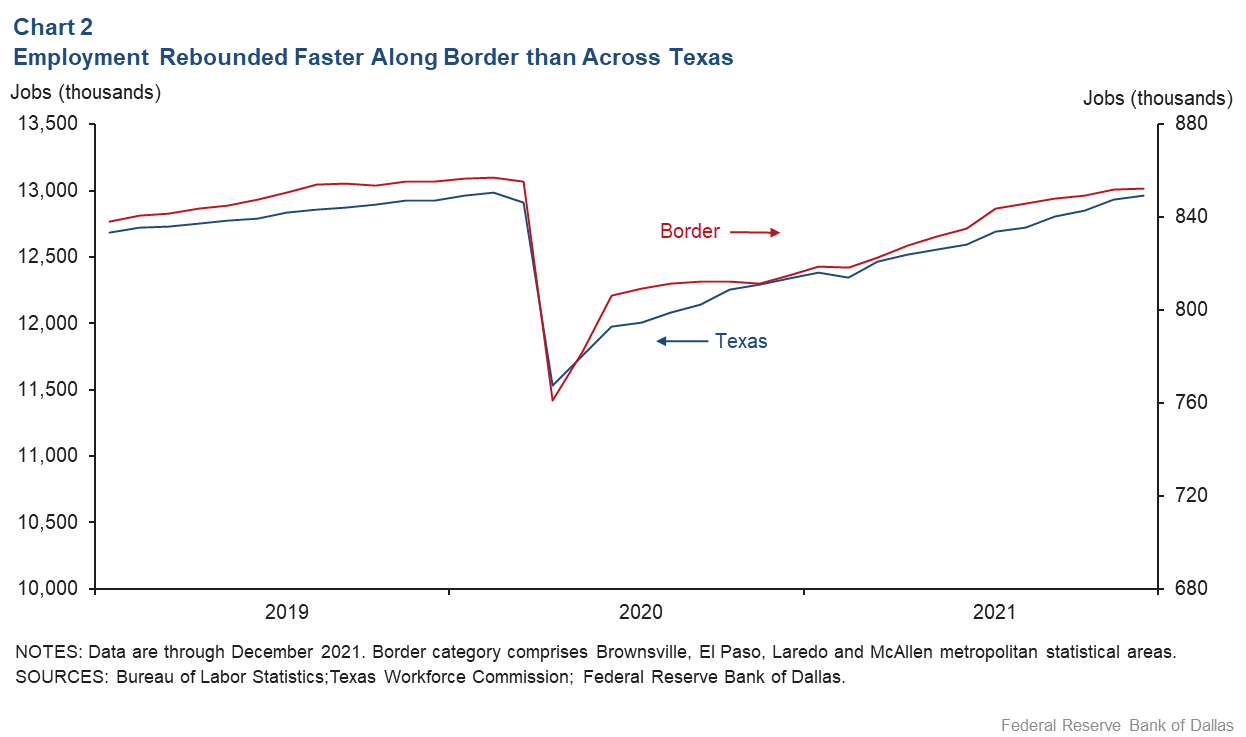

Fiscal stimulus helped the border region overcome the initial pandemic-induced decline in economic activity and employment rebound faster than statewide (Chart 2).

Fiscal stimulus supported local demand and propped up retail sales that otherwise would have plummeted given the loss of cross-border shoppers. Instead, combined inflation-adjusted retail sales for the four major Texas border MSAs were little changed in 2020 (Chart 3).

Border is Ground Zero for U.S.–Mexico Trade

A quick recovery in U.S.–Mexico trade also contributed to the border economy’s timely recovery. Total trade between the two countries fell 43 percent in April 2020 and another 10 percent in May. However, it bounced back in June, growing 64 percent, and in July, rising 14 percent. Trade returned to pre-COVID–19 levels by October 2020.

U.S.–Mexico trade and manufacturing processes have become increasingly integrated through cross-border production linkages since the North American Free Trade Agreement took effect in January 1994 and during the subsequent United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement. While U.S. manufacturers rely on Mexican supply chains, Texas border cities benefit from servicing the trade flows between the two countries. A Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas study in 2013 suggested a 10 percent increase in manufacturing on the Mexican side of the border boosts employment 2.2 percent in Brownsville, 2.8 percent in El Paso, 4.6 percent in Laredo and 6.6 percent in McAllen.

Surging Migration Creates Ripple Effects

After two decades of declining unauthorized border crossings, they surged anew in fiscal year 2021 to a record-high 1.7 million. This supported the border economy because of the concentration of enforcement infrastructure and manpower.

The Border Patrol and other federal agencies initially deployed resources in response to a flood of asylum seekers in 2019 and then to address rising illicit border crossings in 2020 and 2021. Construction and support activity poured into the border—including for more border barriers and detention centers—providing additional fiscal stimulus that boosted local economies.

Overall Texas Economic Growth Includes Border

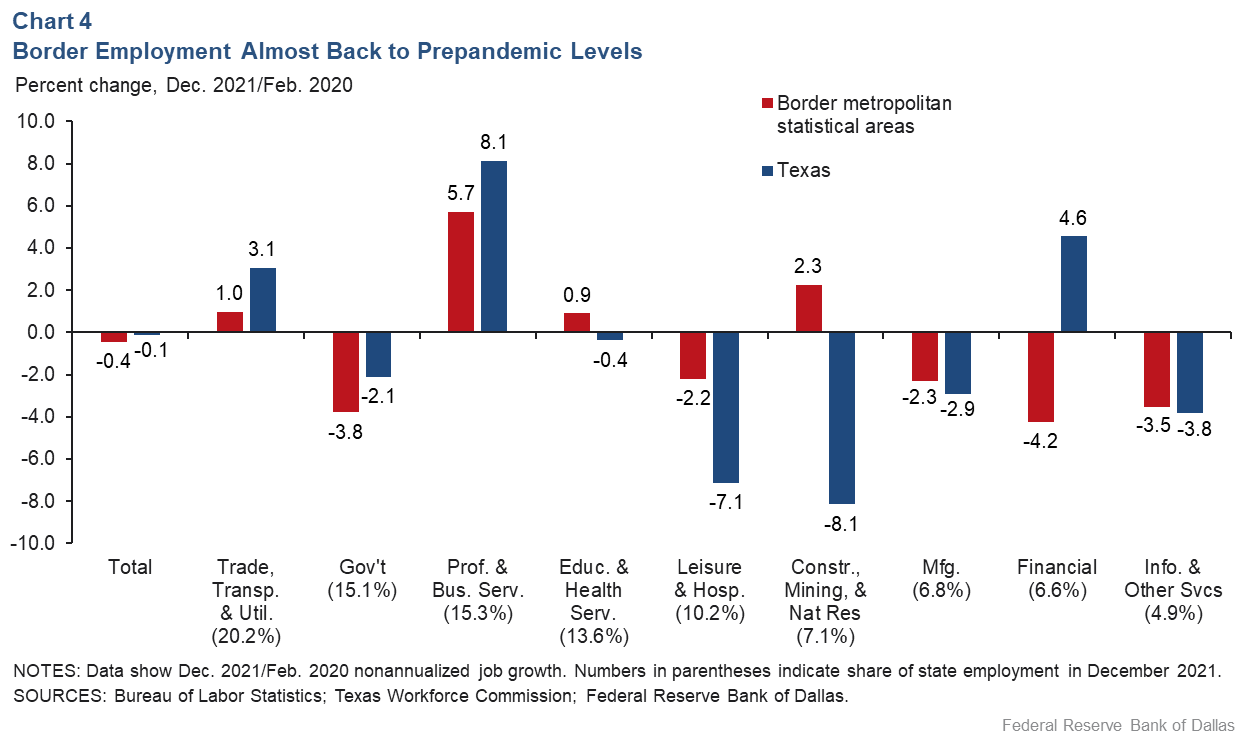

Job losses along the border and statewide have been about the same since the pandemic began. While border employment is 0.4 percent below prepandemic levels, Texas employment is down 0.1 percent (Chart 4).

The border has outperformed Texas in construction and mining, education and health services, manufacturing, information and other services, and leisure and hospitality. Border employment grew nearly 4.6 percent in the year ended December 2021, compared with the state’s increase of 5.1 percent during the period.

Border to Grow Though Challenges Remain

Despite a series of economic challenges since the onset of the pandemic, the border economy has done nearly as well as Texas overall.

Economic growth along the border may slow this year as federal stimulus payments have largely ended and supply-chain bottlenecks continue. However, investment interest in the region most likely will increase, as global manufacturing companies turn their attention to the border to boost supply-chain resilience in a postpandemic world. The reopening of normal border crossing in November 2021 will further support commercial activity.