Russia counters sanctions’ impact with currency controls, averts crisis (for now)

The U.S. and its allies imposed unprecedented trade and financial sanctions on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine. The Russian central bank responded with strict capital controls that have stabilized the value of its currency—the ruble—and prevented a currency or financial crisis.

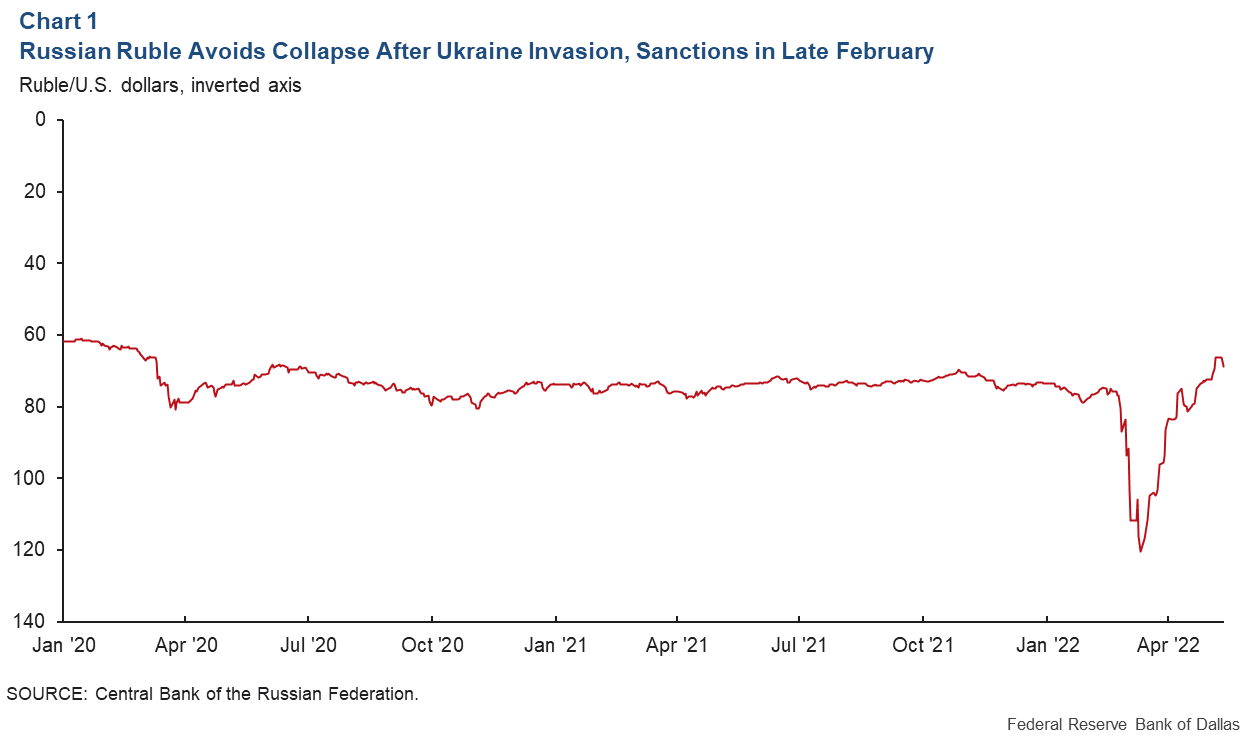

The Russian ruble/U.S. dollar exchange rate was stable through 2020 and 2021 apart from a depreciation at the height of the COVID-19 crisis in March 2020. However, within two weeks following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022, the ruble depreciated sharply from 80 rubles/dollar to 120 rubles/dollar.

The U.S., the European Union and their allies imposed unprecedented economic and financial sanctions on Russia within days of the conflict’s start.

Their aim was to cut Russia off from world financial markets and make it impossible to finance the war. The sanctions prevented western banks from transacting with key Russian counterparts and sidelined several Russian banks from the world interbank payment system. The sanctions also froze the accounts of the Russian central bank denominated in allied currencies—effectively rendering half of the central bank’s foreign exchange reserves unusable.

Russia’s central bank responded by sharply increasing interest rates and imposing strict capital controls that appear to have prevented capital flight and stabilized the ruble. Less than two months after economic and financial sanctions, the ruble and financial system avoided collapse, and the currency regained its preinvasion level (Chart 1).

Russia’s balance of payments crisis in 2014

To understand the central bank’s actions and the ruble’s dramatic fall and subsequent rebound, we step back to look at the 2014 Russian balance-of-payments crisis. It, too, was driven by western sanctions in response to actions in Ukraine, most notably the annexation of Crimea. Those sanctions were not nearly as harsh as the ones imposed in 2022, though the previous curbs were meant to reduce capital inflows into Russia.

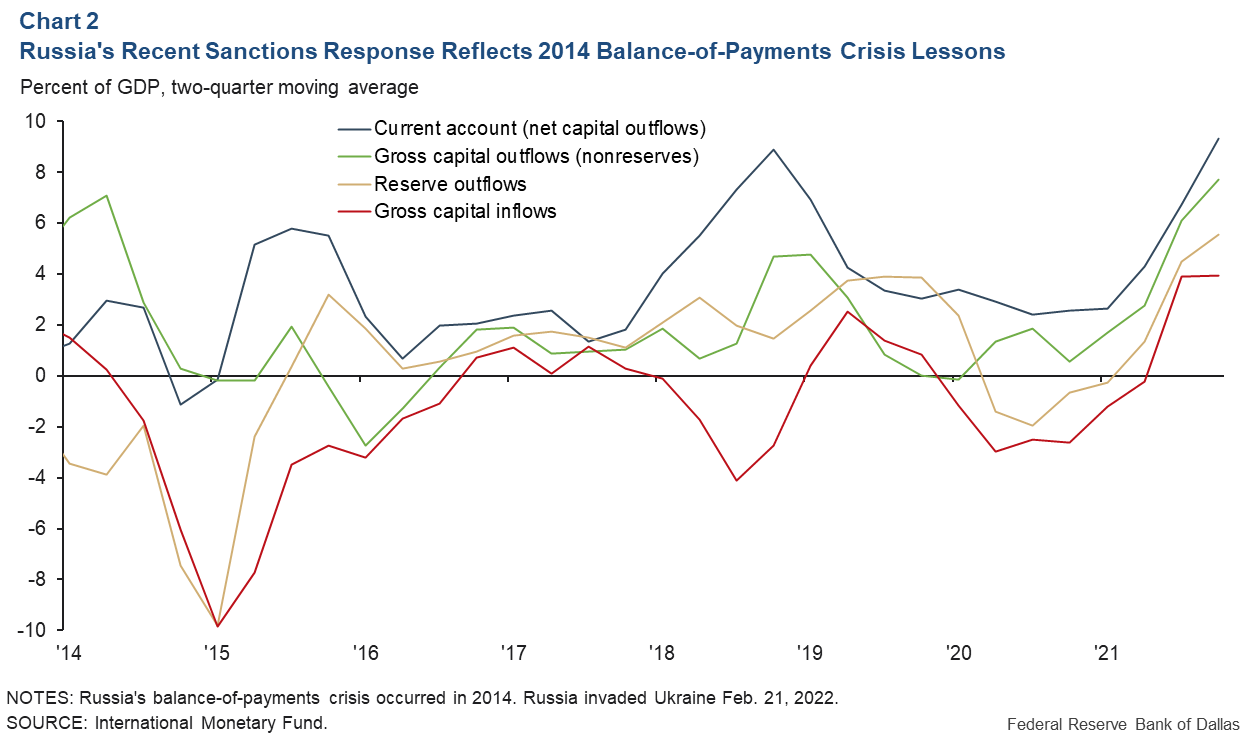

Chart 2 plots Russian balance of payments going back to 2014: gross capital inflows (net purchases of Russian assets by foreign residents), gross capital outflows, nonreserves (net purchases of foreign assets by Russian residents, not including central bank foreign exchange reserves), reserve outflows (the purchase of foreign exchange reserve assets by the central bank) and the current account (net capital outflows, gross outflows plus reserve outflows minus gross inflows).

The chart begins with the onset of the balance-of-payments crisis—gross inflows fell sharply between first quarter 2014 and first quarter 2015. Gross inflows as a share of GDP fell by more than 11 percentage points. This is a two-standard-deviation fall in gross inflows, meeting the definition of a “sudden stop” in capital inflows.

As in many cases of sudden stops, such a sharp drop in foreign capital inflows precipitates a currency or financial crisis—Russian companies and individuals struggled to obtain the foreign financing necessary to roll over existing debt and finance imports.

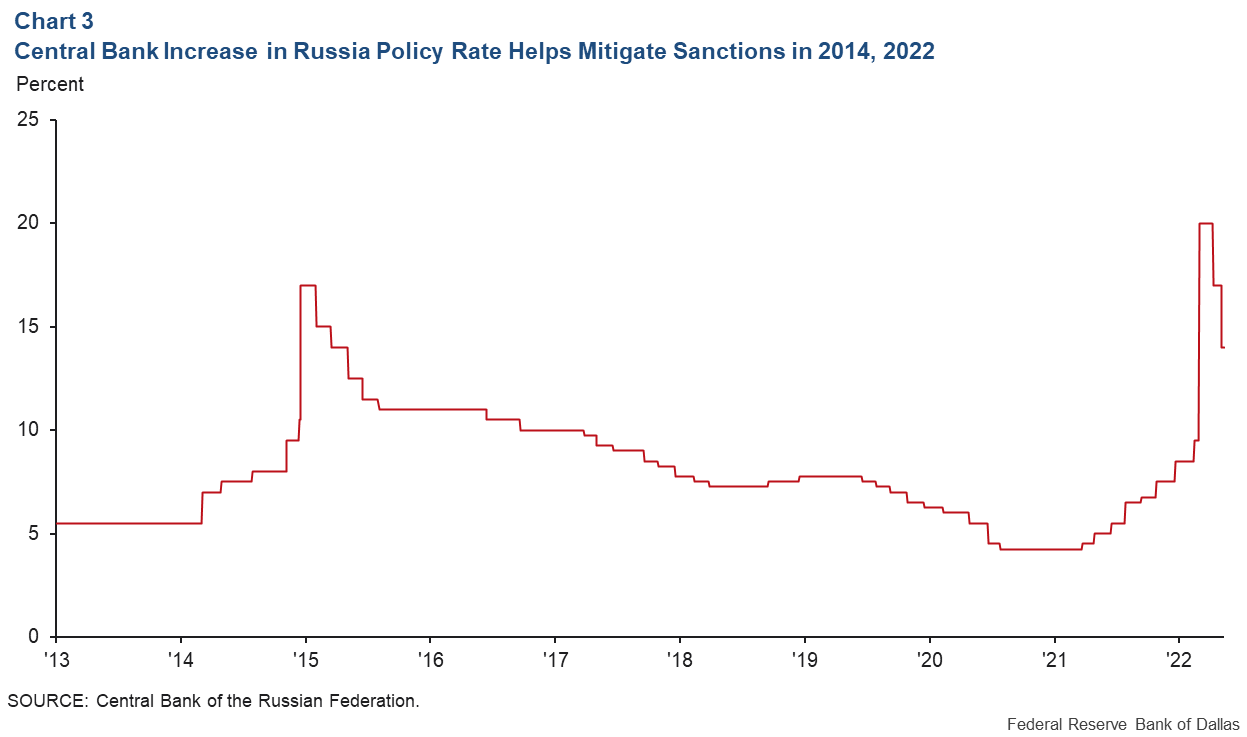

The Russian central bank responded with two policy actions. The first (as shown in Chart 2) was a massive sale of foreign-exchange reserves. The second was a sharp increase in domestic interest rates (Chart 3).

The central bank raised its policy interest rate by a total of 1,150 basis points (11.5 percentage points) in 2014. The first of these interest rate moves took place in an unscheduled meeting in the days after the annexation of Crimea in late February, and the most dramatic of these interest rate moves was a 650-basis-point increase at an unscheduled meeting in December.

The sale of foreign exchange reserves reduced total gross capital outflows. Likewise, raising the domestic interest rate would incentivize Russian residents to hold domestic assets instead of foreign ones, again reducing gross outflows. Between first quarter 2014 and first quarter 2015, gross outflows as a share of GDP (both nonreserve outflows and central bank reserve flows) fell by more than 12 percentage points, a “retrenchment” in gross outflows that offset the sudden stop in gross inflows.

Responding to sanctions during 2022 crisis

Eight years later, and Russia was again faced with sanctions over actions in Ukraine that will lead to a sudden stop in gross capital inflows into Russia.

The sanctions are tougher and include a freeze on the accounts of the Russian central bank, effectively removing foreign exchange intervention as a tool of the central bank to offset the fall in gross inflows. If successful, these sanctions would bring about a currency collapse—a global dumping of rubles and de facto devaluation—making it impossible for Russia to finance its war in Ukraine.

Russia’s central bank raised the domestic interest rate by 1,050 basis points in an unscheduled meeting three days after the Ukraine invasion in late February. Because the sanctions prevent foreign exchange reserve sales, the central bank responded with strict capital outflow controls. Russian residents are forbidden from moving foreign currency abroad and face a strict limit on the amount of foreign currency they can withdraw from Russian banks over the next six months. Russian companies that earn revenue in foreign currency must exchange 80 percent of that foreign currency with the central bank for rubles.

In a recent article, we showed that theoretically, central bank foreign exchange intervention is equivalent to capital controls—the two instruments are substitutes for preventing a balance of payments crisis. In 2014, the central bank sold foreign exchange reserves to reduce total gross capital outflows. In 2022, the central bank uses capital controls to directly suppress nonreserve capital outflows.

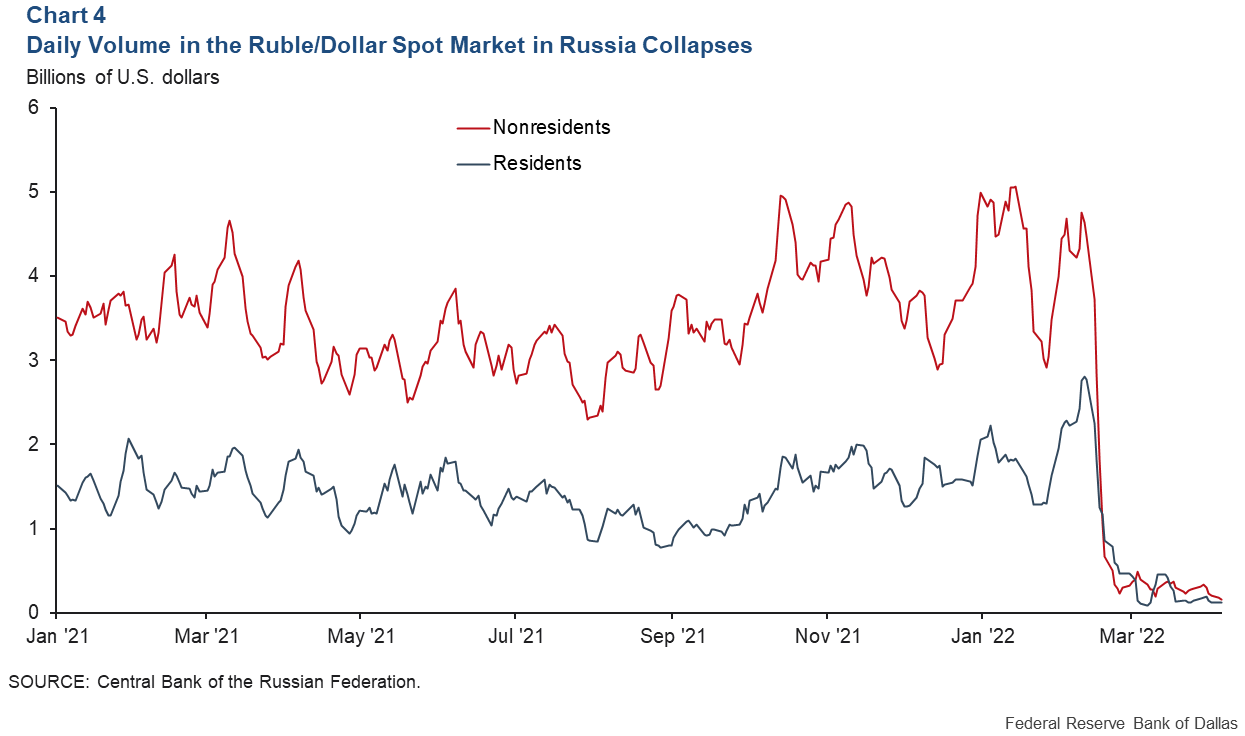

The daily turnover in the Russian ruble–U.S. dollar spot market at Russian banks and at the Moscow Exchange illustrates how access to foreign exchange dollars has been limited (Chart 4). This daily turnover collapsed to near zero in late February/early March. This is the impact of sanctions (preventing ruble asset purchases by nonresidents) and capital controls (preventing dollar asset purchases by residents).

War cost may determine sanctions’ currency, financial system impacts

Capital controls seem to have prevented capital outflows and stabilized the value of the ruble in the short run. Whether the capital controls continue to hold in the future is uncertain, but if they do, the Russian balance of payments will have found a stable equilibrium with financial autarky.

At the end of 2021, Russia ran a large current account surplus. This is foreign capital flowing into Russia through its trade surplus. Before the war, Russian exports—such as oil and natural gas—were more than enough to finance Russian imports and keep the currency and financial system stable.

A big unknown is the cost of the war. If the cost is high, then Russia could not finance the war with export earnings alone. But if the cost of waging the war is smaller, then the Russian currency and balance of payments will remain stable despite the severe foreign financial sanctions.

About the authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.