Existing low-rate mortgages blunt impact of recent rate surge

Mortgage rates reversed sharply in 2022 as the Federal Reserve aggressively raised interest rates to curb inflation. The rate on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage averaged 6.9 percent in October, the highest since May 2002, according to Freddie Mac.

This rate, however, represents the market rate on new mortgages that only account for a small fraction of the overall mortgage stock; it isn’t the rate the typical borrower pays.

A large difference exists between the market rate and the average outstanding mortgage rate, based on residential mortgage servicing data. As of September 2022, most mortgage borrowers had locked in ultra-low rates, suggesting that recent rate hikes have had a limited effect on a typical borrower’s debt service expenditures.

From a policymaker’s perspective, the prevalence of low-rate mortgages suggests that future policy rate cuts may not as effectively stimulate household spending through mortgage refinancing as during past recessions.

Tracing pandemic-era average outstanding mortgage rates

How has the average outstanding mortgage rate evolved since the pandemic? To address this question, I use the McDash dataset provided by Black Knight, a financial services and data analytics provider. This dataset consists of the portfolios of the largest U.S. mortgage servicers, covering two-thirds of loans in the residential servicing market (approximately 34 million loan-level records per month).

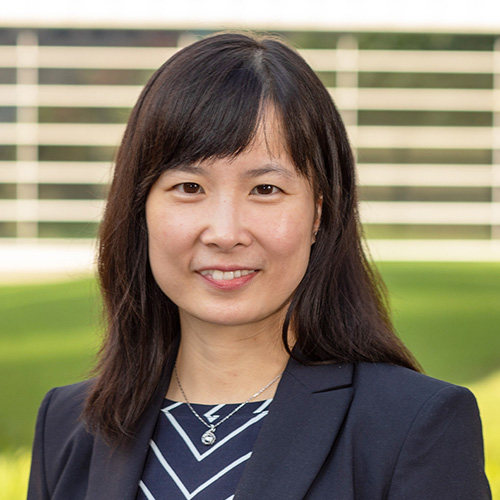

My analysis is restricted to first-lien owner-occupied mortgages. For comparison, the average rate on new mortgages implied by the McDash data moves fairly closely with the commonly cited Freddie Mac 30-year mortgage rate with a one-month lag (Chart 1). Both fell sharply in 2020 and stayed near 3 percent for most of 2021 before surging above 5 percent in mid-2022.

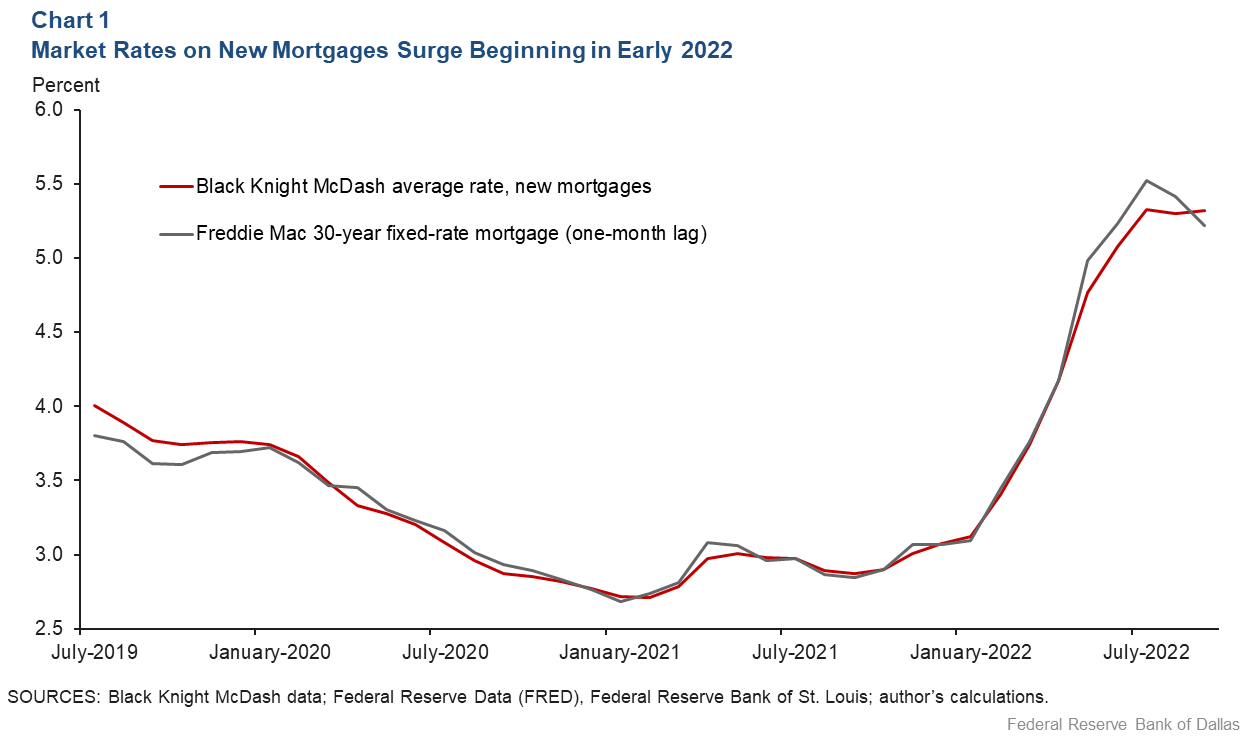

In contrast, the evolution of the average rate on all outstanding mortgages is much smoother (Chart 2). This rate declined steadily from 4.4 percent in July 2019 to 3.7 percent in March 2022. While rising slightly in recent months, it remained below 3.8 percent in September, suggesting that the average borrower is paying a very low mortgage rate.

The notable difference between the two mortgage-rate measures in Chart 2 arises because long-term fixed-rate mortgages (accounting for 96 percent of the mortgage stock) dominate the U.S. residential mortgage market. This institutional feature slows pass-through of the market rate to the average outstanding rate.

The average outstanding rate approaches the market rate as buyers finance home purchases with new mortgages, or borrowers refinance loans at the market rate. During periods of rising interest rates, demand for refinancing tends to fall, further slowing the pass-through of the market rate to the average mortgage borrower.

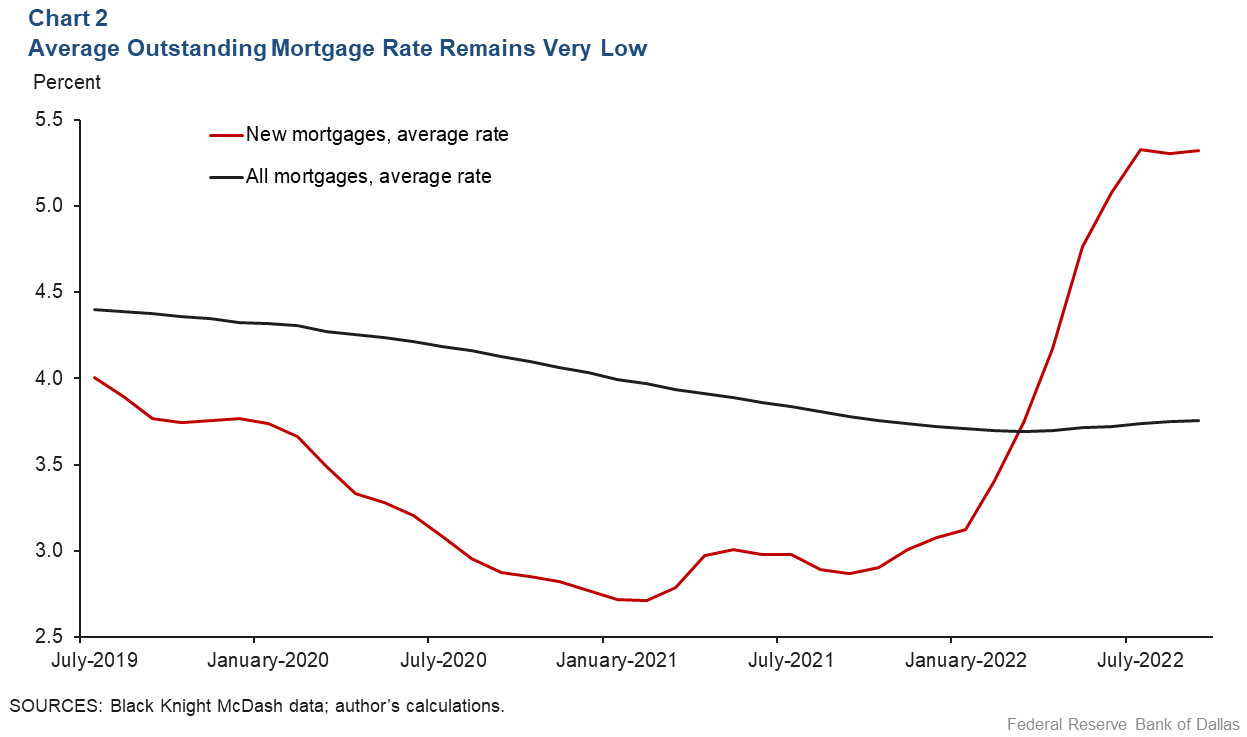

Chart 3, which illustrates how the mix of mortgages has evolved, plots the proportion of outstanding mortgages with rates exceeding 4 percent. The proportion fell substantially from 56 percent in July 2019 to 28 percent in March 2022. In September 2022, just 31 percent of outstanding mortgages had a rate exceeding 4 percent.

Refinancing dries up, slowing market-rate pass-through

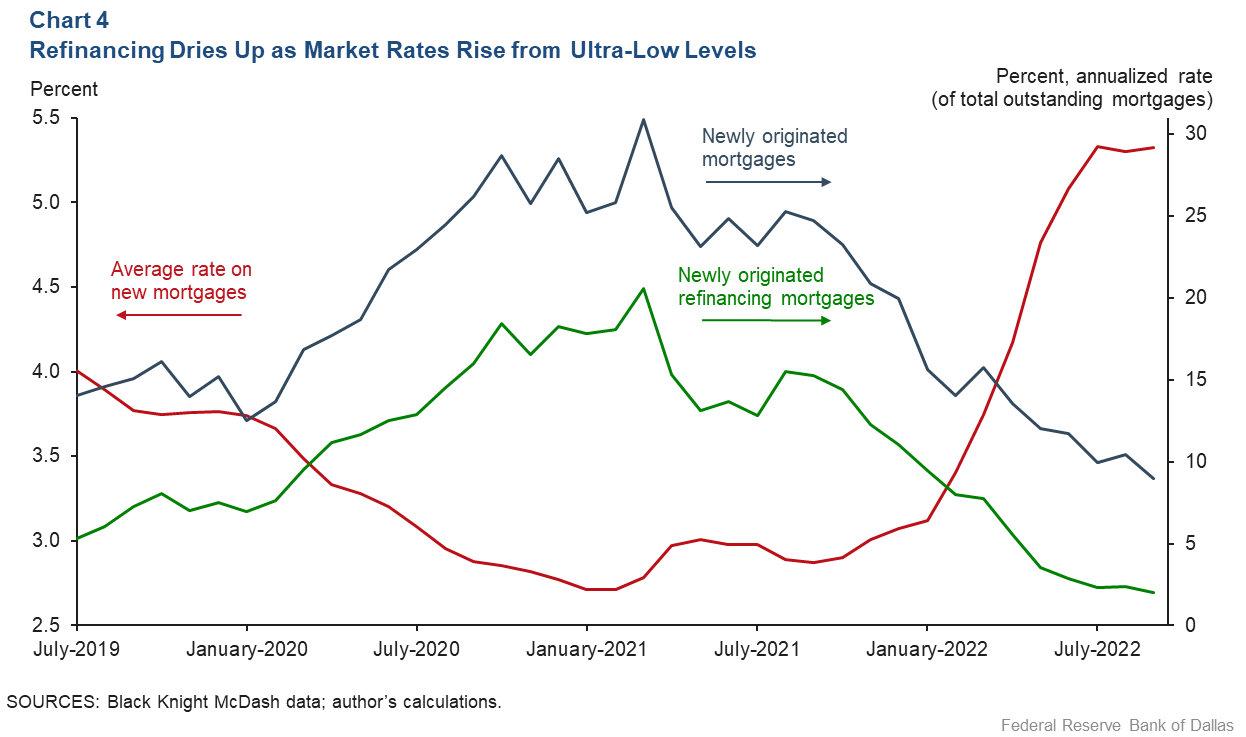

Refinancing activity cooled at a rapid race during the 2022 rate-hike cycle. Refinance applications dropped to their lowest level since October 2000, down 84 percent in September 2022 from the year-prior level, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. Looking ahead, refinancing activity is likely to remain subdued given elevated market rates and the Federal Open Market Committee participants’ assessment that the target policy rate will stay above its long-run level for several years.

Moreover, many borrowers have locked in ultra-low rates in the past two years, further making a new wave of refinancing unlikely. The proportion of outstanding mortgages that are newly originated increased from 14 percent (at annualized rates) before the pandemic to 31 percent in early 2021 and remained higher than the prepandemic level throughout 2021 (Chart 4). This pattern was mainly driven by a refinancing boom over this period.

The typical U.S. homeowner spends 13 years in their home, according to Redfin, a residential real estate brokerage. This implies that, as refinancing activity dries up, it will take at least several years for the average mortgage borrower to experience a meaningful increase in the borrowing rate as a result of the recent rate increases.

Weighing the impact of future rate cuts on refinancing, consumption

Due to the prevalence of long-term fixed-rate mortgages prepayable without penalties, one might expect that when the Federal Reserve eventually cuts interest rates, it would spur refinancing and, hence, consumption among mortgage borrowers.

Studies show that this happened during previous recessions. Historically, a 1-percentage-point decline in the market mortgage rate has led to an aggregate consumption increase of 0.5–1.5 percent.

The same monetary policy action, however, may have different impacts, depending on the mortgage rate paid by the typical borrower. For example, unlike the current situation, in November 2008 (when the Fed’s first quantitative easing was announced), the average outstanding mortgage rate was 6.2 percent, and the prevailing market rate was 6.1 percent.If the Federal Reserve lowers the policy rate at a time when most borrowers still have ultra-low mortgage rates, they will not benefit from mortgage refinancing, and the effect of the policy stimulus on these borrowers’ consumption will be muted. This is the path-dependent feature of monetary policy emphasized in recent academic studies.

The efficacy of a monetary stimulus depends on the distribution of potential refinancing benefits. This distribution, however, reflects past monetary policy actions.

About the Author

Xiaoqing Zhou

Zhou is a senior research economist and advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.