Policy impact of unexpected Fed rate movements blurred by key information cues

Unexpected Federal Reserve monetary policy moves can profoundly affect market participants, investors and the economy. The impact of policy stems not only from its direct effects—the traditional focus for economists—but also from the new information revealed about the Fed’s economic outlook.

The direction and magnitude of the effect of monetary policy depends on identifying these two channels, the pure policy shock and the information shock, and assessing their relative strengths.

After parsing out the information shock portion of Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) interest rate surprises, we find that pure policy shocks are more prominent than the overall effect of any policy surprise, which includes the information shock.

The consequences of greater-than-expected interest rates due to a pure policy shock are contractionary and include lower inflation, economic activity and stock prices and higher bond risk premia. By comparison, a positive interest rate surprise that is perceived as an information shock signals better-than-anticipated data about the economy, leading to higher prices, economic activity and stock prices and lower bond risk premia.

Exploring new information about policy, central bank outlook

To illustrate the importance of parsing new information about the economic outlook from the Fed’s actions, suppose that policymakers surprisingly loosen interest rates. The first effect is a market expectation adjustment regarding future interest rates—a lower cost of borrowing encourages economic activity. This is the pure policy channel.

The second effect is an inference of worsening economic conditions, as the Fed generally lowers interest rates in times of economic stagnation. The Fed’s private information that leads to the policy decision causes the unanticipated decision to function as a market signal—the Fed information effect and associated information shock.

Disentangling the policy and information channels is important to consumers, investors, academics and policymakers who are interested in the effect of monetary policy on the economy and financial markets. The direction and magnitude of the resulting impact depend on the relative strength of these two channels. This task is challenging because common measures of the economy’s reaction to interest rate surprises is a synthesis of both channels.

Some researchers impose the restriction on their econometric models that positive policy rate surprises attributable to the Fed information effect—positive information shocks—increase stock prices. Such an assumption seems plausible on the surface because positive information shocks signal a better state of the economy.

However, the net effect of a rate increase revealing good economic news could be positive or negative for stock prices. Higher expected corporate cash flows increase the value of stocks. Nevertheless, investors also must consider the value of future corporate cash flows. The interest rate increase implies a higher cost of capital, which suggests a company must earn more in the future to achieve the same value in terms of today’s dollars, creating a negative impact on stock values.

To address this challenge, our research isolates the pure policy shock from the information shock in monetary policy (interest rate) surprises. We draw upon interest rate changes on macroeconomic-data release days to separate information shock effects from the pure policy shock impacts.

While interest rate movements following the Fed’s policy actions can reflect surprises about the Fed’s policy stance and its information signals, the interest rate movements on macroeconomic-data release days are driven solely by the revelation of new economic information. These movements can, therefore, help us parse out the information shock component of Fed policy.

Selecting indicators to assess shocks

We study the impact of pure policy and information shocks on the one-year Treasury yield, the logarithm of the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index and the industrial production index, the excess bond premium and the logarithm of cumulative returns on the S&P 500 Index.

Taking the logarithms of variables allows us to capture their rate of change. The excess bond premium is the component of corporate bond credit spreads that represents investors’ attitude toward risk, after parsing out the probability of corporate default. The excess bond premium, along with the logarithm of cumulative returns on the S&P 500, indicate overall financial conditions in the economy.

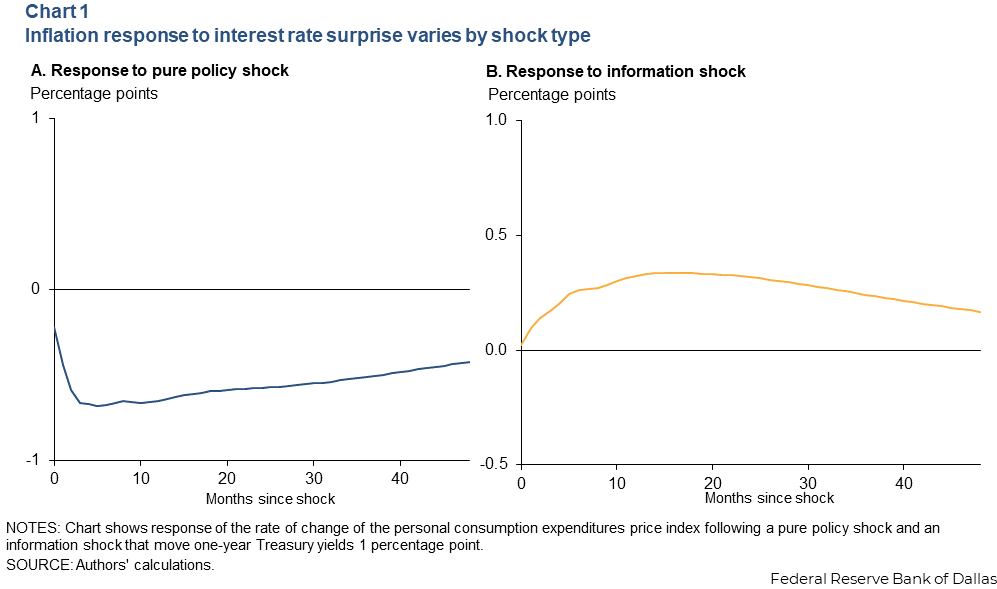

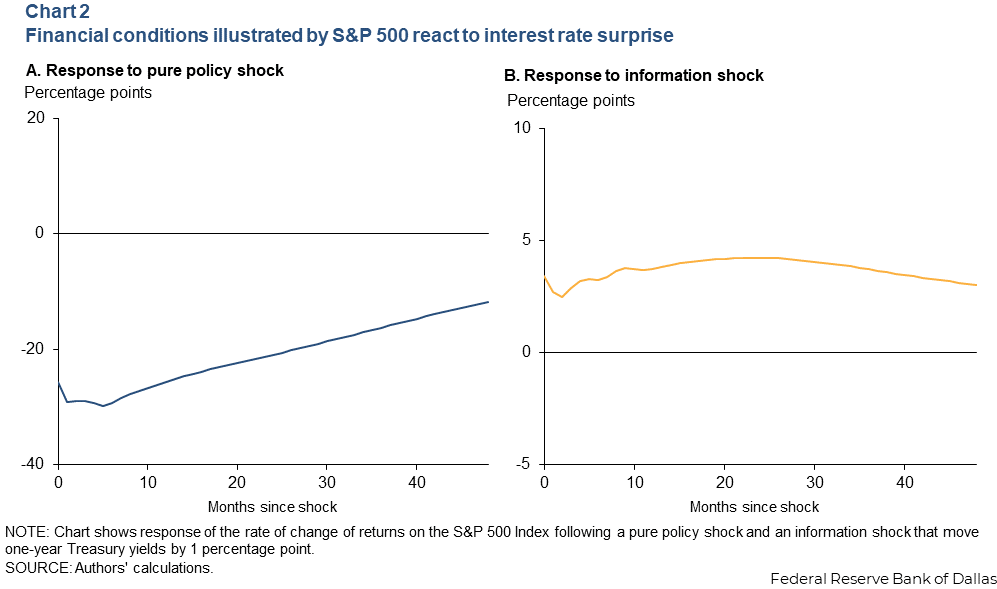

Chart 1 depicts the impact on the PCE price index of a pure policy shock and an information shock that increases the one-year Treasury yield by 1 percentage point. Chart 2 depicts the impact of the same shocks on the S&P 500.

We see that the two channels have qualitatively opposite effects on price and stock indexes, although both have the same effect on the interest rates. In particular, the pure policy shock depresses both the price level and stock values. This result is consistent with the notion that contractionary monetary policy lowers inflation and economic activity.

In contrast, the information shock increases both the price level and stock values. This result is consistent with the notion that an information shock associated with a rate increase signals better-than-expected economic activity. In the case of stock values, this result also implies that markets expect higher future cash flows due to good news about the economy, which overshadows the negative effect of higher discount rates.

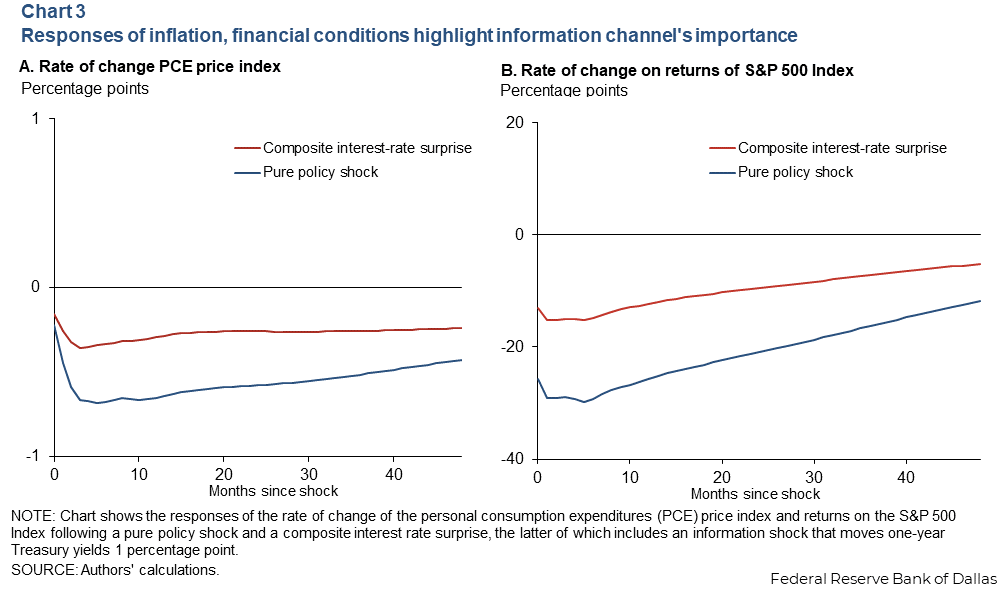

Next, we compare the responses to the pure policy shock with the responses to the policy surprise without parsing out the responses to new information.

Chart 3 illustrates the pure policy shock effects and the composite interest-rate surprise effects on the PCE price index and S&P 500. We see that the impact of the pure policy surprise is more prominent than the effect of the composite interest-rate surprise.

These findings validate recent literature that emphasizes the importance of the information-channel effect. If it were not pronounced, the variables in Chart 3 would exhibit similar, if not identical, impacts. However, the pure policy shock effects are more than twice as large as the composite interest-rate surprise.

Pure policy shock predominates

Our research suggests that the pure policy shock—cleaned of any information shock effects—more strongly affects the economy than interest rate surprises that include both shocks.

We find positive interest-rate surprises due to pure policy shocks have a contractionary impact on the economy, while such interest rate surprises due to information shocks reveal better news about the economy and, therefore, have an expansionary impact. The negative effect of higher discount rates is offset by the higher expected future cash flows from the stronger economic news.

About the authors

The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.