Texas natives likeliest to ‘stick’ around, pointing to state’s economic health

How well does each state keep its native residents? Based on a calculation measuring the share of people born in each state who still live there, Texas is the nation’s “stickiest” state. The natives aren’t leaving.

Since the pandemic, shifts in population—from states like California and New York to destinations such as Texas and Florida—have been well documented. These numbers measured everyone leaving a state—whether they were born there or not. But which states are best at retaining their native residents—in other words, the stickiest? And why does it matter?Economic health key to state stickiness

The share of people born in a state and who stay there can provide an important measure of its attractiveness to workers. The stickiness of native residents is also key to maintaining a stable (or growing) population and workforce, which is vital to economic growth.

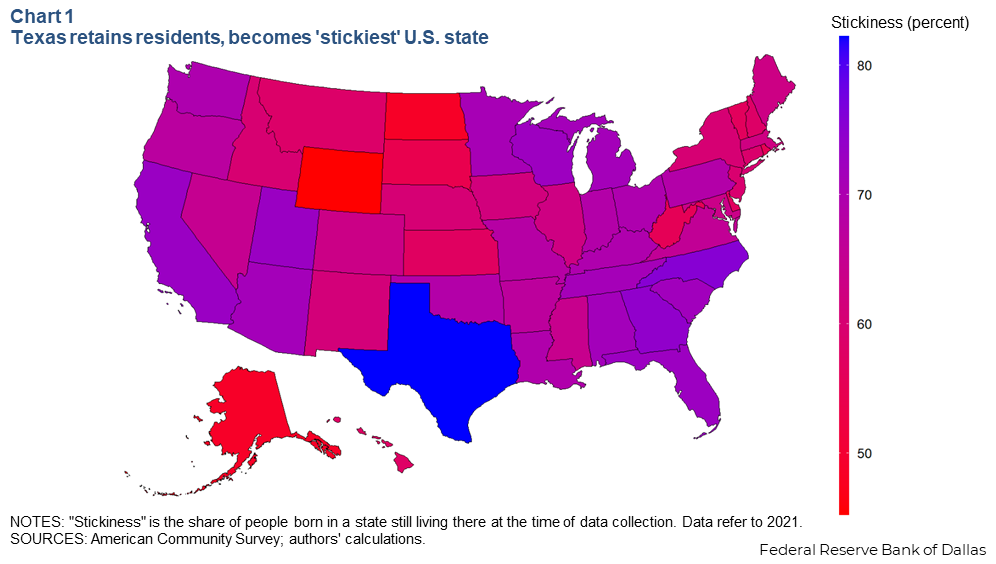

To figure out which states are best at retaining their native residents, we calculated the stickiness of each state. Using American Community Survey (ACS) data, we estimated the share of people born in each state who still lived in that state as of the 2021 survey (Chart 1).

Texas is the stickiest state in the country by far, with approximately 82 percent of native Texans still living here in 2021. Other sticky states include North Carolina (75.5 percent), Georgia (74.2 percent), California (73.0 percent) and Utah (72.9 percent).

At the other end of the spectrum, Wyoming is the least-sticky state, with only 45.2 percent of natives remaining there. North Dakota and Alaska were the only other states with less than half their native population staying there (48.6 percent and 48.7 percent, respectively). Rhode Island (55.2 percent) and South Dakota (54.2 percent) round out the bottom five.

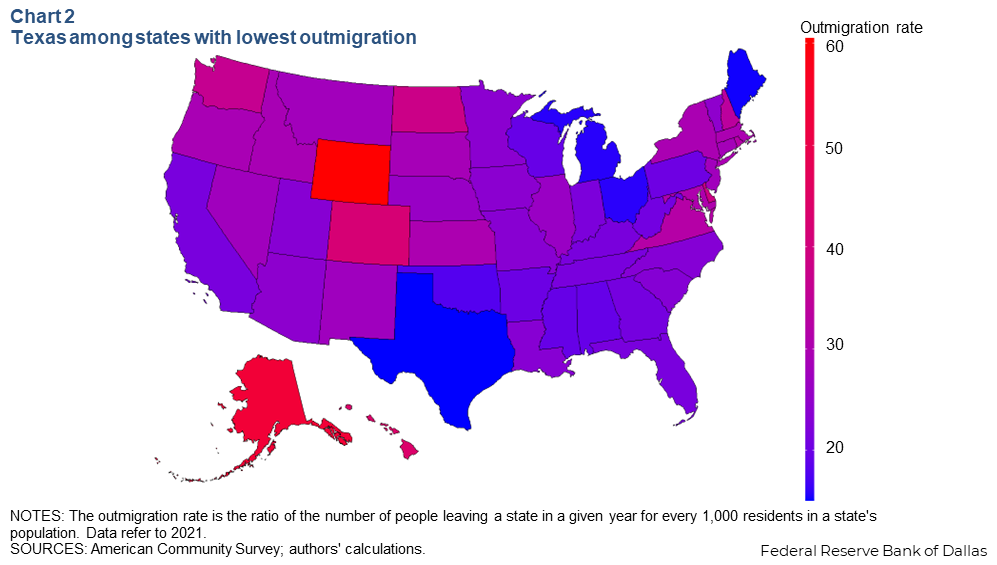

Notably, the least-sticky states tend to see high levels of outmigration of everyone—not just their native residents (Chart 2).

Overall outmigration numbers track everyone moving from one state to another state, including both people born there and those who moved there before leaving, making them a better indicator of population flows.

In addition to being the stickiest state, Texas had the lowest outmigration rate in 2021, followed by Maine and Michigan. Wyoming, Alaska and Hawaii experienced the highest outmigration rates.

What makes a state sticky?

Sticky states, where the weather is often warmer, tend to offer better economic conditions than nonsticky states. These conditions can be in the form of better and more varied job opportunities or less burdensome tax policies. Without sufficient employment opportunities, native residents may be pushed to other states to seek good jobs.

The five stickiest states each recorded above-average job growth between 2010 and 2019, meaning there was less pressure for residents to leave to find work. Four of the five stickiest states also have below average state and local tax burdens. Residents born in low-tax states may be hesitant to move to high-tax states, as the additional obligation will reduce take-home pay and may lower their standard of living.

States with multiple cities are at an advantage for stickiness because they can provide native residents with a wider variety of in-state job opportunities and relatively higher wages compared with smaller or less-populous states with fewer urban areas.

Altogether, the five stickiest states have 15 metropolitan statistical areas with populations exceeding 1 million; among the five least-sticky states, there is only one such metro (Providence, Rhode Island). Even when including smaller cities, those top stickiest states have 28 metros with 500,000 or more residents versus still just one among the bottom five.

State size, as in the case of Texas, also has the potential to burden would-be movers with longer distance and, thus, higher relocation costs. Residents can more readily leave a small state for a nearby one while remaining close to existing social and professional networks. They can also live in one state and work in another, like residents of New Jersey who work in New York.

To leave a geographically larger state, residents must move physically farther away, often incurring higher financial and social costs.

Housing costs play important role

High housing costs also have the potential to prompt people to leave a state, both younger and older people. Young people may leave states where they cannot afford to buy a house in favor of more affordable areas, while older people may cash out their housing value to retire somewhere cheaper. Both have the effect of driving people out of their home state.

This trend could help explain low stickiness rates in the Northeast, where the median home price was almost double that of the nation’s in second quarter 2023. That said, California is a notable exception, with high stickiness and high housing costs.

Interestingly, the pandemic didn’t affect stickiness scores much. We find no state’s stickiness score changed by more than 3 percentage points between 2017 and 2021. Even as more people moved during the pandemic, states overall remained just as sticky as they were before.

UPDATE 9/8/2023: Chart 2 corrected to show that the outmigration rate is depicted.

About the authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.