Evolving leveraged loan covenants may pose novel transmission risk

An evolving change affecting the expanding, highly leveraged corporate loan sector may impact how the economy responds to adverse shocks.

The U.S. leveraged (high-yield) loan market has more than doubled in size since the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, growing to nearly $1.2 trillion in outstanding debt by 2019, according to S&P’s Leveraged Commentary and Data. That expansion has been accompanied by concerns about shocks and the impact of leveraged loan defaults on the broader economy.

Leveraged loans are typically found on the balance sheets of heavily indebted firms. Major changes to financial covenants have accompanied the wider use of leveraged loans, with incurrence covenants (as opposed to maintenance covenants) rapidly gaining prominence. While both types of covenants stipulate borrowers meet specified financial metrics, the consequence of not meeting them differs.

The longstanding maintenance covenants require transfer of control to lenders, while incurrence covenants only restrict certain predetermined actions by corporate managers, such as dividend payments or new debt issuance. Thus, incurrence covenants are viewed as providing less protection for creditors and posing greater systemic risk. As a result, leveraged loans with incurrence covenants have acquired the cov-lite nickname.

The recent paper “High-yield debt covenants and their real effect” explores the relationship between violation of incurrence covenants (latent violations) and subsequent borrower behavior. The paper finds that failure to meet financial metrics that underlie incurrence covenants leads to outcomes similar to violating maintenance covenants. Both are characterized by a significant and sudden decline in the borrower’s investment activity.

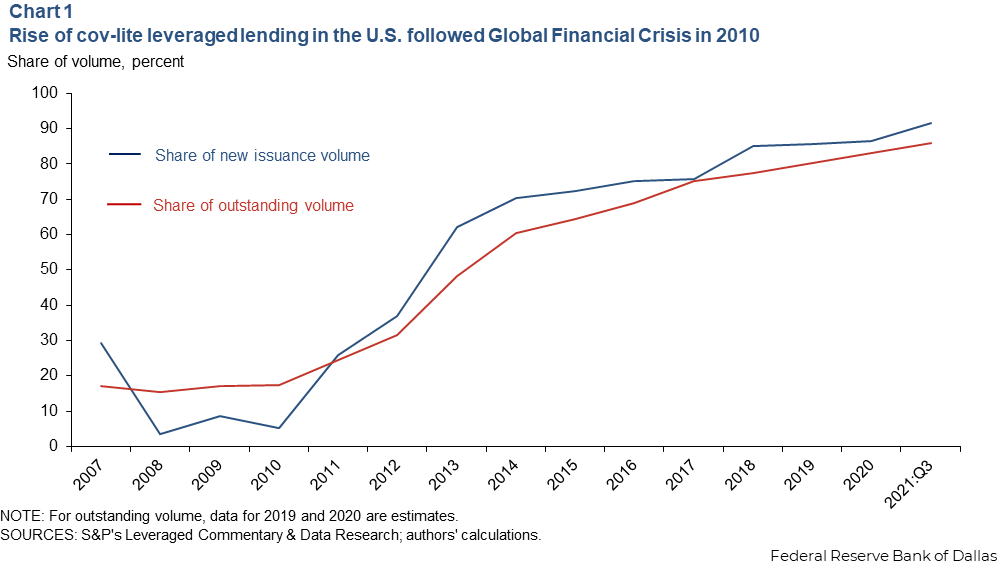

Cov-lite loans have increased from about one-fifth of total leveraged loans in 2007 to more than 86 percent of outstanding volume in 2021 (Chart 1). More than 90 percent of new issuance carried incurrence covenants in 2021.

U.S. policymakers and legislators have taken note of the emergence of cov-lite lending. In 2019, former Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen expressed concern about the “deterioration in lending standards” in the U.S. leveraged loan market. More broadly, inadequate creditor protection and risky borrower behavior could amplify the impact of negative economic shocks.

The paper’s findings, however, suggest protections provided by incurrence covenants are not significantly less effective than maintenance covenants. Nevertheless, since the impact of incurrence covenants kicks in before a borrower’s bankruptcy or default, the covenants provide a novel transmission mechanism for economic shocks.

Lending practices change after 2008

The increasing prevalence of incurrence covenants after 2008 is intertwined with the growth of the U.S. leveraged-loan market. Typically, firms with relatively low credit ratings use leveraged loans as an alternative to high-yield bonds (also known as junk bonds). These loans are also used as bridge financing for merger and acquisition activity.

To lower risk to lenders, leveraged loans are widely syndicated to institutional investors, with 315 different institutional investors participating in the segment as of 2019. Dozens to hundreds of individual participants may invest in a leveraged loan.

Incurrence covenants were traditionally a feature of conventional corporate bonds because a transfer of control under a maintenance covenant is difficult to coordinate among larger groups of bondholders. The number of creditors involved in the leveraged-loan market creates a similar coordination issue, which prompted the broader shift from maintenance covenants to incurrence covenants.Borrowers reduce investment after covenant violations

Loan contract information from Standard & Poor’s Leveraged Commentary & Data database and from individual loan agreements filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission offer a view of the behavior of borrowers following both incurrence and maintenance covenant violations in the leveraged loan market.

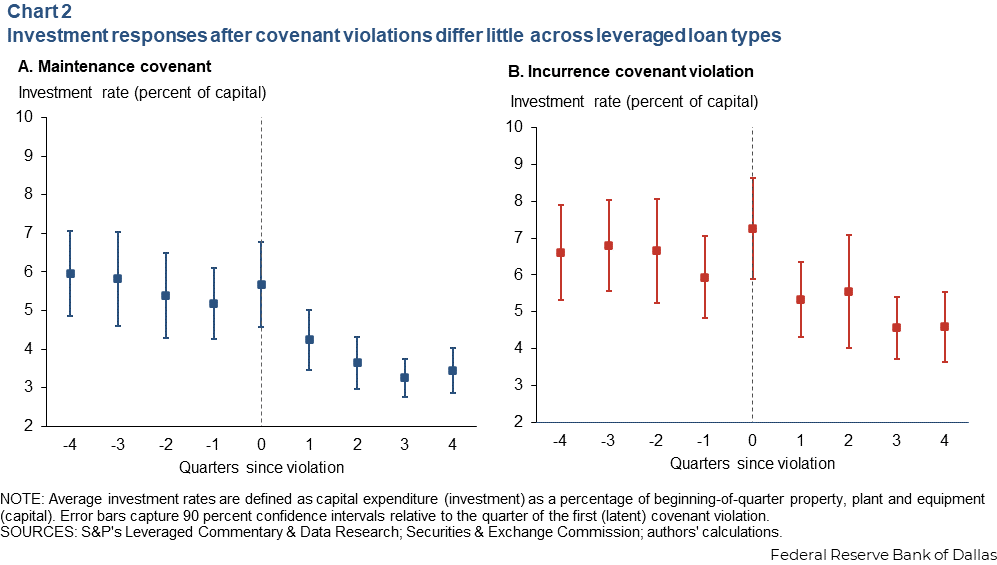

An economically significant decline in investment occurs immediately following both maintenance and incurrence covenant violations (Chart 2). This challenges the assumption that incurrence covenants are weaker than maintenance covenants.

Investment rates are calculated by measuring capital expenditures as a percent of total capital and are tracked quarterly in the year prior to and following each type of covenant violation.

Borrowing firms’ investment activity follows a similar pattern on the financial margins of a covenant violation of either type. On average, a borrowing firm’s investment rate decreases by 0.9 percent following a maintenance covenant violation compared with about a 1.8 percent decline after an incurrence covenant breach, once we control for various borrower-level characteristics.

In addition to slowing their investment activity, borrowing firms significantly reduce their debt burden after breaching either a maintenance or an incurrence covenant. A borrower’s debt-to-asset ratio decreases about 1.6 percent after a maintenance covenant violation; after the triggering of an incurrence covenant violation, the decline is roughly 2.7 percent.

The timing and magnitude of the response following either type of covenant violation are similar.

Incurrence covenants strongly affect firms’ investment activities

After incurrence or maintenance covenants are triggered, borrowing firms swiftly and significantly decrease their investment activities and reduce their leverage. This consistent behavior change contradicts the common perception that incurrence covenants are less protective of creditors.

The relationship points to a novel mechanism for the propagation of adverse economic shocks, with contractual constraints playing an important role in transmitting shocks to the highly leveraged corporate sector, even prior to bankruptcy or default.

Given the growing size of the leveraged loan market, this mechanism could be an important factor in the economy's response to adverse shocks.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.