Has the opioid crisis peaked in Texas and the U.S.?

The modern U.S. opioid crisis began in the 1990s with the rising abuse of prescription opiates such as OxyContin, or oxycodone as it’s generically known. A crackdown on legal opiates in the 2010s led to increased use of illegally sourced opiates, especially fentanyl. Deaths rose sharply across the nation, peaking in 2022 at 112,109, a rate of 33.6 deaths per 100,000 people compared with a rate of 22.7 per 100,000 in 2019 before the pandemic.

Unlike chronic diseases that typically impact the elderly, the opioid crisis disproportionately affects young adults and working-age people, exacting high social and economic costs. Nationally, estimates of the annual cost of the opioid crisis exceed $1 trillion per year. While state figures vary, one study estimated Texas’ yearly costs exceeded $100 billion, which includes medical expenditures, public safety spending, and lost earnings and productivity.

Despite that expense, the magnitude of overdoses in Texas hasn’t been as high as elsewhere. Among the possible reasons are an economy that offers opportunities that make drug use less appealing; demographics, including a large Hispanic population that historically has appeared less inclined to opioid overdosing, and comparatively less use of the powerful synthetic narcotic fentanyl.

After years of mounting deaths and costs from opioid addition, recent declines in both Texas and the nation suggest the worst may have passed.

Overdose rates vary across the nation

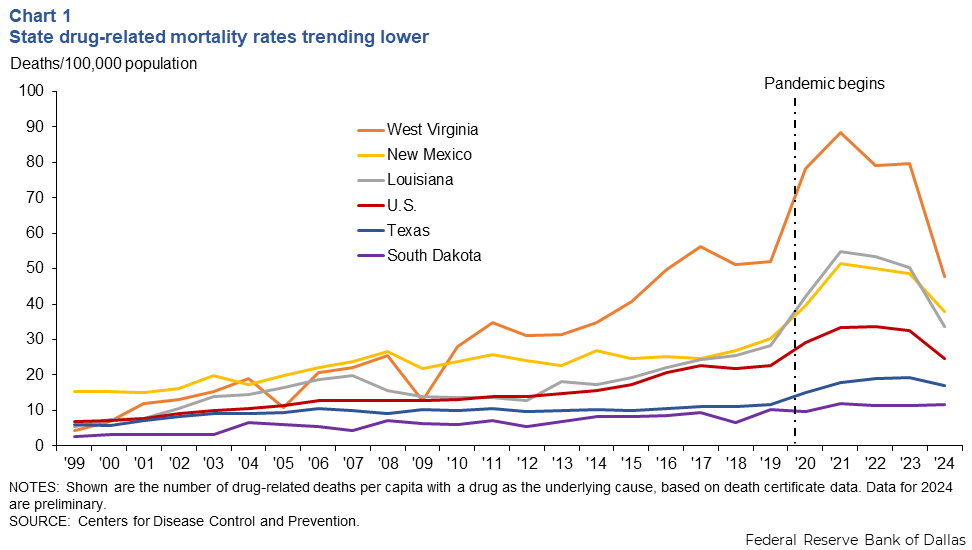

Although the opioid crisis has been researched extensively, researchers still do not understand the reasons for the regional variation in its intensity. Some states, such as West Virginia, have been hit hard, while others, such as South Dakota, have remained relatively less affected (Chart 1).

Texas had an average drug-related mortality rate less than one-third that of West Virginia from 1999–2023. This difference was even more pronounced during the height of the opioid crisis in 2022. Texas averaged 11 deaths per 100,000 over the period (19 in 2022), while West Virginia averaged 36 deaths per 100,000 (79 in 2022). Louisiana and New Mexico have higher mortality rates than Texas, but lower than West Virginia. The median state rate was 33 deaths per 100,000 at the peak in 2022.

At least three factors may help explain Texas’ lower overdose rate. Lower uptake of fentanyl is one. It is the leading cause of drug deaths. Yet, despite Texas’ proximity to the southern border, a main source of illegal fentanyl, only 34 percent of Texas overdoses between 2019 and 2023 involved fentanyl. The state rate is nearly half the U.S. rate, 62 percent. New Mexico and Louisiana also trail the national percent of overdoses from fentanyl.

A larger Hispanic population appears to be another factor. Hispanics, making up 40 percent of Texas’ population, experience a significantly lower drug overdose mortality rate than other groups. In 2022, non-Hispanic Texans died at a rate of 23 per 100,000, while Hispanics died at a rate of 13 per 100,000. Notably, the Hispanic overdose death rate has been rising rapidly.

Finally, favorable economic factors may play a role. Plentiful economic opportunity, rising wages and low unemployment could help explain Texas’ lower death rate from drugs. A lack of jobs and chronic poverty correlate with higher drug mortality.

U.S. opioid abuse has long history

Opioid abuse is not just a 21st century phenomenon. After the Civil War, many Americans injected morphine or ingested opioids in medicines. In the 1960s and ’70s, heroin abuse emerged, notably in Vietnam, where studies found 20 percent of U.S. enlisted personnel were afflicted.

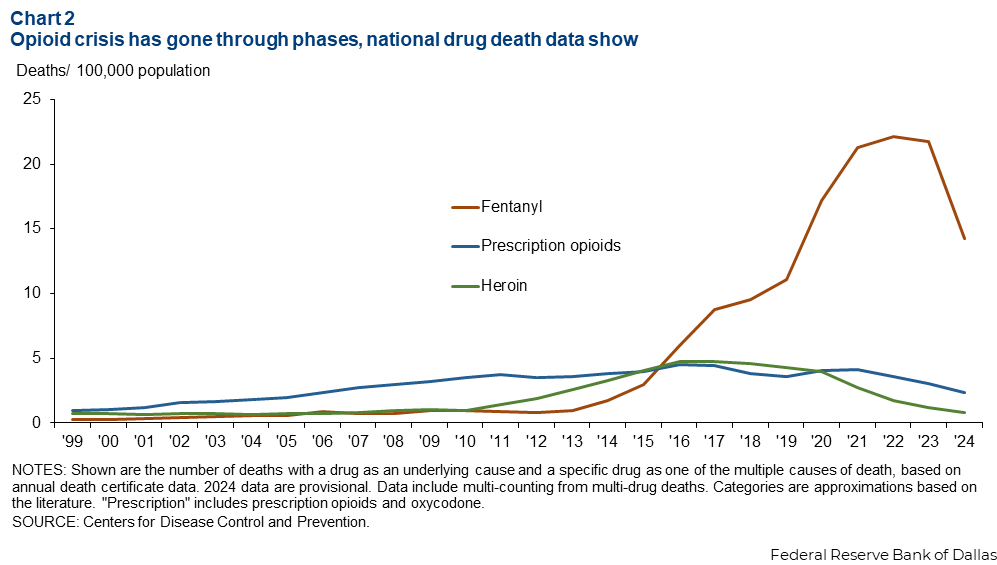

The modern opioid crisis is characterized by phases. Prescription opioids dominated early on, followed by the rise of heroin and the surge of fentanyl. Death certificate data by type of opioid causing death illustrate the evolution (Chart 2).

Aggressive marketing and overprescription of long-release OxyContin and short-release opioids, such as Vicodin and Percocet, prevailed in the mid-1990s. After OxyContin was reformulated to make it harder to abuse and many states increased oversight over prescription opioids in the mid-2010s, research suggests some users switched to heroin.

Increasing prescription drug abuse preceded the widespread use of fentanyl, a potent, fully synthetic opioid. While there have been past outbreaks of fentanyl use, the current one is significantly larger.

Fentanyl-based overdoses dominate the ongoing phase of the opioid crisis, particularly affecting states east of the Mississippi River. Most recently, deaths have increased from polydrug use, typically fentanyl and a stimulant.

Non-fatal overdoses are the unseen side of the opioid crisis, with 8.4 non-fatal overdoses for every fatal overdose in 2019.

Texas established the Opioid Abatement Fund Council in 2021 to spend $1.6 billion the state is to receive over an 18-year period from a multi-state lawsuit settlement with 13 pharmaceutical companies that the states had alleged caused the opioid crisis.

Supply of opioids evolves

Availability and cost are key to the origin of the opioid crisis. It started with legal prescriptions—hospitals, pharmacies, outpatient facilities and pill-mill pain clinics—before shifting to illegal sources.

More than 40 percent of those misusing painkillers in 2024 obtained them from friends or family, according to the 2024 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health. (Drugs obtained legally but used illegally count as misuse.)

By 2024, 82 percent of those who abused fentanyl used illegally-made fentanyl, up from 69 percent in 2022. About 70 percent of fentanyl pills seized in the U.S. in 2019 are believed to have been manufactured in Mexico, likely using precursor chemicals sourced from China. The federal government has increased enforcement at the border with Mexico to thwart fentanyl trafficking.

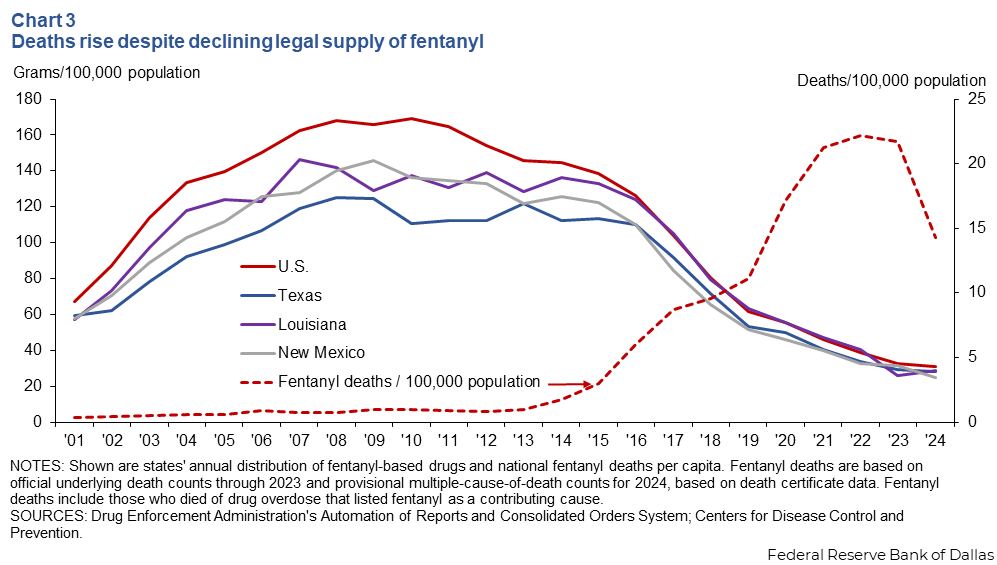

While the legal supply of fentanyl peaked in 2010, fentanyl deaths continued rising until 2022 (Chart 3). The data also highlight the regional variation in legal fentanyl supply. Texas, New Mexico and Louisiana are below the national average of per capita distribution of legal fentanyl.

Demand for opioids appears to decline

In 2024, 3.0 percent of Americans misused opiates (8.6 million), down from 3.6 percent in 2021. This includes the misuse of prescription opioids and the use of heroin and illegally made fentanyl. (Please see box below.) For context, only 0.3 percent of European Union adults misused opioids (860,000) in 2023, the latest date for which data are available.

Researchers first noticed the opioid crisis among low-educated, middle-age non-Hispanic white males. Opioids were considered a contributing factor to a rise in mortality among this group beginning in the late 1990s and are part of the trend economists term “deaths of despair.” Though most people who die from drug use are non-Hispanic whites, the drug crisis affects non-Hispanic blacks, whites and Native Americans at similar rates.

The highest drug-related death rate in most states is among working-age adults (ages 25 to 64). The overdose rate among men is about twice that of women. The gender gap has increased with the prevalence of fentanyl. Education plays a role as well. The mortality rate from drug overdoses for men with high-school education or less is 25 times that of women with bachelor’s degrees or higher.

The type of opioids consumed during different stages comes with a demographic shift in fatalities. From 1999 to 2010, when prescription opioids dominated, the share of deaths involving young adults (ages 20 to 39) and males declined. After 2010, when the fentanyl phase began, those shares rose.

In some areas with disproportionate concentrations of strenuous physical occupations—manufacturing, mining and agriculture—opiates got an early hold due to the prevalence of on-the-job injuries. Because of this, some research has used mining sites as a proxy for the demand for opioids for pain relief.

Research tends to find more evidence of correlation than causation when investigating the link between adverse economic conditions and opioid use and deaths. Identifying causality is difficult, as the relationship works both ways: job loss may trigger opioid overdoses, but opioid use also affects the likelihood of participating in the labor force.

One study found that counties experiencing relative economic decline experienced greater increases in drug mortality than those with more robust growth. However, the relationship was weak and mostly explained by confounding factors. The study concluded that changes in economic conditions accounted for less than one-tenth of the rise in drug and opioid-involved mortality rates.

State and federal attempts to address the crisis have focused on limiting the legal and illicit supply.

Prescription drug monitoring programs curtail the phenomenon known as doctor shopping. Similar regulations target pill mills operating as clinics. A Johns Hopkins University study found that opioid prescriptions fell 23 percent in the year following Texas’ implementation of a 2009 law restricting pill mills. In 2020, Texas also mandated that doctors check an online database of prescriptions.

Some research suggests such laws drive the trade underground. Restricting legal prescriptions resulted in users resorting to illegal sources, which proved deadlier.

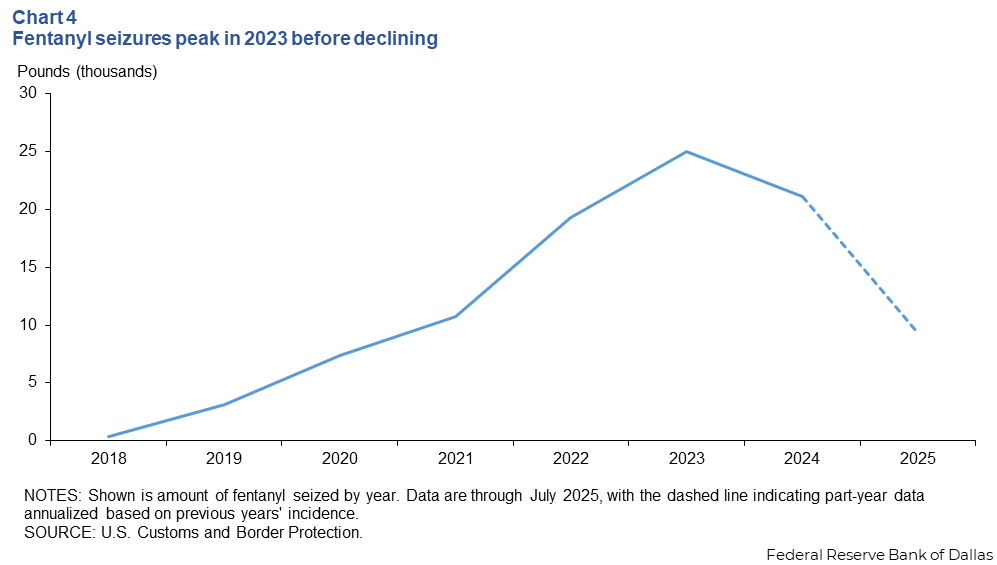

Targeting illegally manufactured fentanyl coming across the nation’s borders, especially Texas’ southern border, is another tactic. Fentanyl seizures dramatically increased and then fell over the past five years, according to Customs and Border Patrol data (Chart 4).

If seizures restrict the fentanyl supply, then fentanyl prices should rise and deter users. However, despite increased enforcement, the price of illegally manufactured fentanyl fell 17 percent annually from 2016 to 2021.

Curiously, some policies to regulate opioids are associated with a decrease in overdoses, while others are associated with an increase. Recent research shows that a critical factor in the success of opioid regulation is the difference between the prices of illegal and legal opioids. If authorities regulate legal opioids when illegal opioids are relatively cheap, users are incentivized to substitute one for the other.

Another option is refocusing enforcement on reducing lethality by specifically targeting dealers who sell drugs laced with fentanyl and distributing test strips to users.

Demand-side strategies target deterrence

Demand-side mitigation strategies typically focus on deterrence and harm reduction.

Increasing criminal penalties for illegal drug use or sale is one example. Drug dealers in Texas and Louisiana can be charged with murder in fatal fentanyl overdoses. Additionally, Texas and Louisiana allow involuntary commitment for those with substance use disorder, while New Mexico does not.

However, punitive deterrence measures alone may fall short of addressing the root causes of drug use and addiction.

Harm reduction is another option. It can involve rescue drugs that reverse drug overdoses and prevent death. For example, New Mexico was the first state to pass a law allowing residents to obtain and administer the drug naloxone (Narcan). New Mexico was also the first state to pass a Good Samaritan Law, granting immunity from prosecution to drug users who seek medical care. Texas implemented naloxone access in 2015 and passed its Good Samaritan Law in 2021.

Research suggests that while Good Samaritan Laws have no statistically significant impact on mortality, states with Narcan access laws experienced a 9 to 10 percent decline in opioid mortality after implementation.

Harm-reduction efforts can also involve long-term medical treatment for substance use disorder, including with methadone and buprenorphine. Methadone and buprenorphine bind to the same receptors in the brain as opiates, reducing withdrawal symptoms and cravings. Users treated with them have less than one-third the overdose risk of those who aren’t. Expanding provider capacity and treatment duration could also lead to a significant decline in opioid overdoses.

States vary in the degree to which they pursue medicine-assisted treatment for substance abuse disorder. The extent of buprenorphine distribution (measured in grams per drug death) shows that some states, including Nevada and Texas, distribute relatively small amounts of recovery drugs. Others, such as Montana, Kentucky and Vermont, distribute relatively large amounts.

One factor in states’ distribution of medicine-assisted treatment is federal funding under the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid. Cuts to these programs could diminish efforts to expand harm mitigation for opioid use disorder.

Drug deaths remain elevated despite gains

Drug overdose deaths fell 27 percent nationwide in 2024 from prior levels and are at or below prepandemic levels nationally. Texas drug deaths fell 12 percent in 2024 after peaking in 2023. They remain above prepandemic levels.

The recent decline in drug overdose deaths, the majority of which are fentanyl-related, has a few possible explanations. One theory is that most of those who were especially susceptible to drug overdoses have succumbed, while surviving users have adapted to the risks. More users now smoke fentanyl, an ingestion method associated with fewer overdoses than injection.

Increased policing, penalties and fentanyl seizures have brought attention to the opioid crisis, although research on the impact of these measures suggests the effect on overdose deaths may be limited. The more widely-held view is that a successful public health response—the availability of Narcan—has meaningfully reduced deaths.

With the most recent phase of the opioid crisis waning, a new wave is probable. States must remain vigilant for new and emerging drugs. Nitazenes, a family of drugs far stronger than fentanyl, are circulating in Europe and give cause to authorities to stand ready with targeted supply-side policies, demand reduction and harm mitigation.

|

What opioids are, and how officials track drug-related mortality

|

About the authors