Texas economic activity sharply falls in wake of COVID-19

Economic distress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has sent the Texas economy into a tailspin. Virus containment measures have prompted unprecedented declines in demand and triggered mass layoffs, shaking business and consumer confidence.

Activity in the service sector has been more severely affected than in manufacturing, precipitating downward pressures on wages and prices. The state’s oil and gas sector has been decimated. The housing market has slowed, too, as sellers and buyers take a wait-and-see approach.

Consumer confidence in Texas plunged in April to its lowest level in seven years, according to data from the Conference Board. In March, the Texas Leading Index registered its steepest one-month decline since the series’ inception in January 1981.

Economic activity will remain weak in the near term. It is likely that Texas will underperform the U.S. in job and output growth this year due to the state’s outsized share of vulnerable industries—such as food services and air transportation—as well as prolonged weakness in the oil and gas sector. According to the Dallas Fed estimates, employment will contract sharply through midyear, rebound in the second half of 2020 and end the year down 7.6 percent on a December-over-December basis.

Texas payrolls fall prior to surge in layoffs

Employment contracted at an annualized 4.7 percent (52,120 jobs) in March—the largest drop since April 2009, during the financial crisis. Declines spanned most industries, pushing up unemployment to 4.7 percent from a near-historical low of 3.5 percent in February. The March jobs report did not fully reflect the economic damage the virus caused because the reference period fell in mid-March, just as stay-at-home orders were implemented across the state.

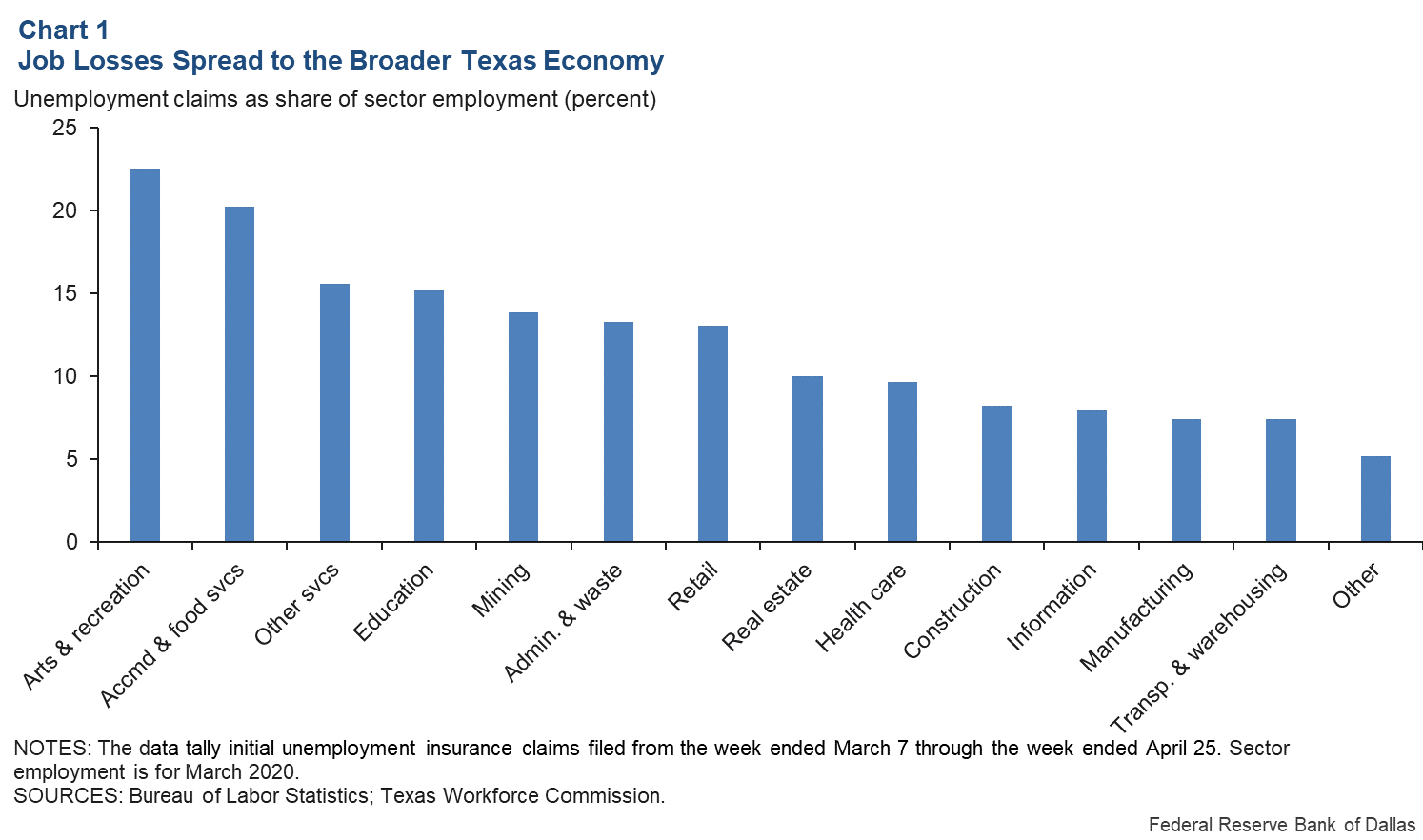

Initial jobless claims are timelier than employment data. They indicate 1.6 million Texans filed for unemployment insurance from mid-March through late April. Layoffs have been widespread across sectors, including health care, where revenues have been hit hard due to declines in routine care visits and cancellations of elective procedures (Chart 1). Layoffs have been particularly notable in arts and recreation as well as accommodation and food services. Job losses in retail, other services, education and mining have been steep as well.

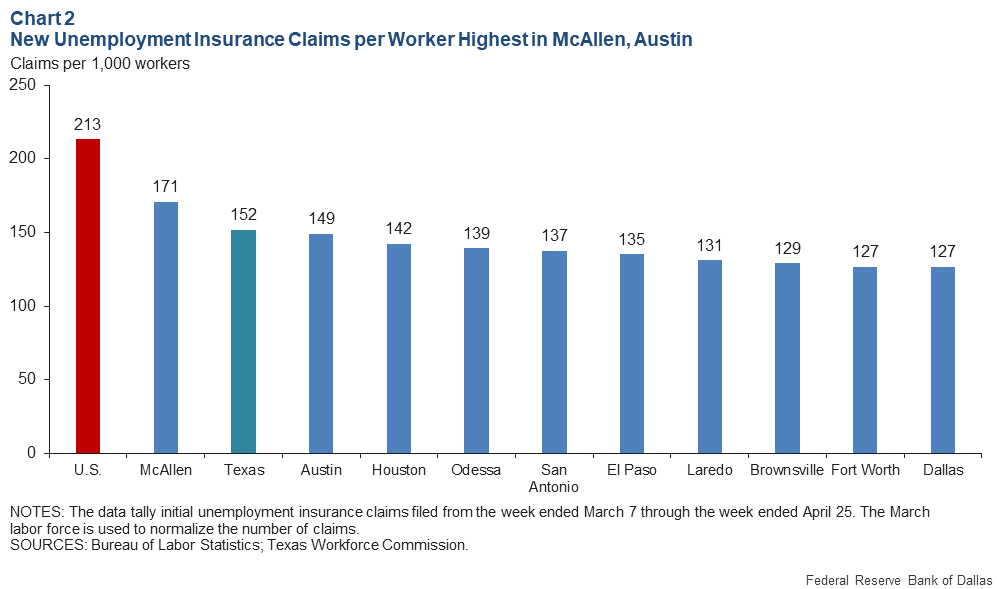

Among the metros, McAllen and Austin have had the highest number of jobless claims per worker (Chart 2). McAllen’s higher concentration of workers in retail and home health services has made it vulnerable. Surprisingly, Austin, which boasts a larger share of workers with a remote working option than other major Texas metros, experienced a wave of layoffs. This is likely due to a large tourism sector that was gearing up for the annual South by Southwest conference in mid-March, which was canceled, as well as start-up firms that saw needed funding from angel investors and venture capital virtually dry up.

Jobless claims per worker in Houston, Midland and Odessa were below the state average but may accelerate as energy-related layoffs intensify.

Overall, total initial jobless claims per worker in Texas lag the U.S. likely due to significant processing delays, suggesting that while initial claims appear to have peaked, they will likely remain elevated until the claims backlog recedes.

Output and revenue plummet, depressing wages and prices

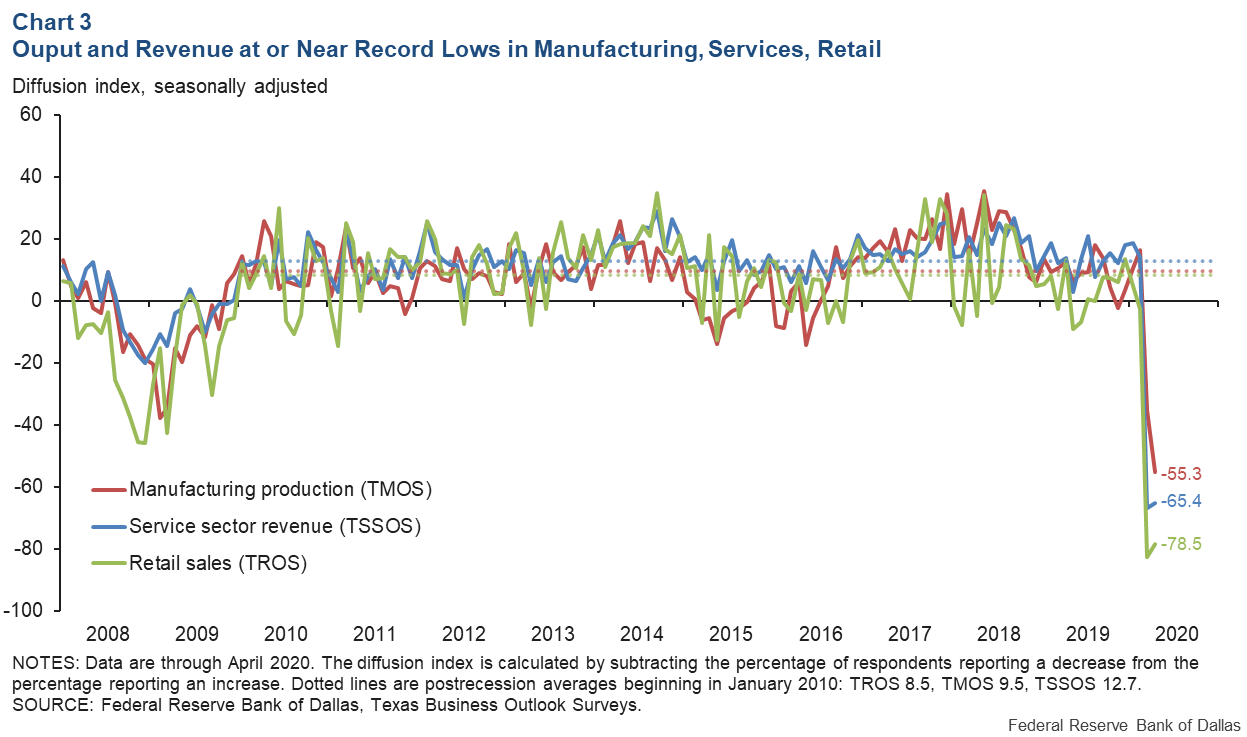

Another timely indicator of Texas growth is data from the April Texas Business Outlook Surveys (TBOS), which show record or near-record declines in most indicators, including the headline indexes (Chart 3). Contraction in the service sector has been more acute than in manufacturing.

Record-high shares of respondents reported depressed activity in April: 74 percent of service firms noted falling revenues, and 65 percent of manufacturers indicated falling output. A historically high share of responding service firms (30 percent) and retail firms (40 percent) said they reduced pay, possibly to conserve cash amid dwindling revenues, sending wage and benefit indexes to new lows. Prices plummeted broadly, responding to weak demand.

This is the first time since mid-2009 that wages and prices in the manufacturing and service sectors simultaneously decreased. Outlooks among respondents were overwhelmingly negative.

Service firms expect leaner payrolls

In a set of special questions posed to TBOS respondents about the impact of COVID-19, the share of firms noting a negative impact on output, demand, hours worked, employment and capital spending increased notably from March to April.

Among those seeing falling demand in April, the average decline was a steep 46 percent. Of those noting layoffs, 75 percent said the reductions were temporary. Among those reducing head count temporarily, only 42 percent expect to rehire all furloughed employees and 43 percent anticipate a more long-lasting reduction. Responses from service firms were even more pessimistic; 36 percent expect to fully rehire laid-off workers and 51 percent expect reduced long-term staffing levels.Residential real estate activity weakens

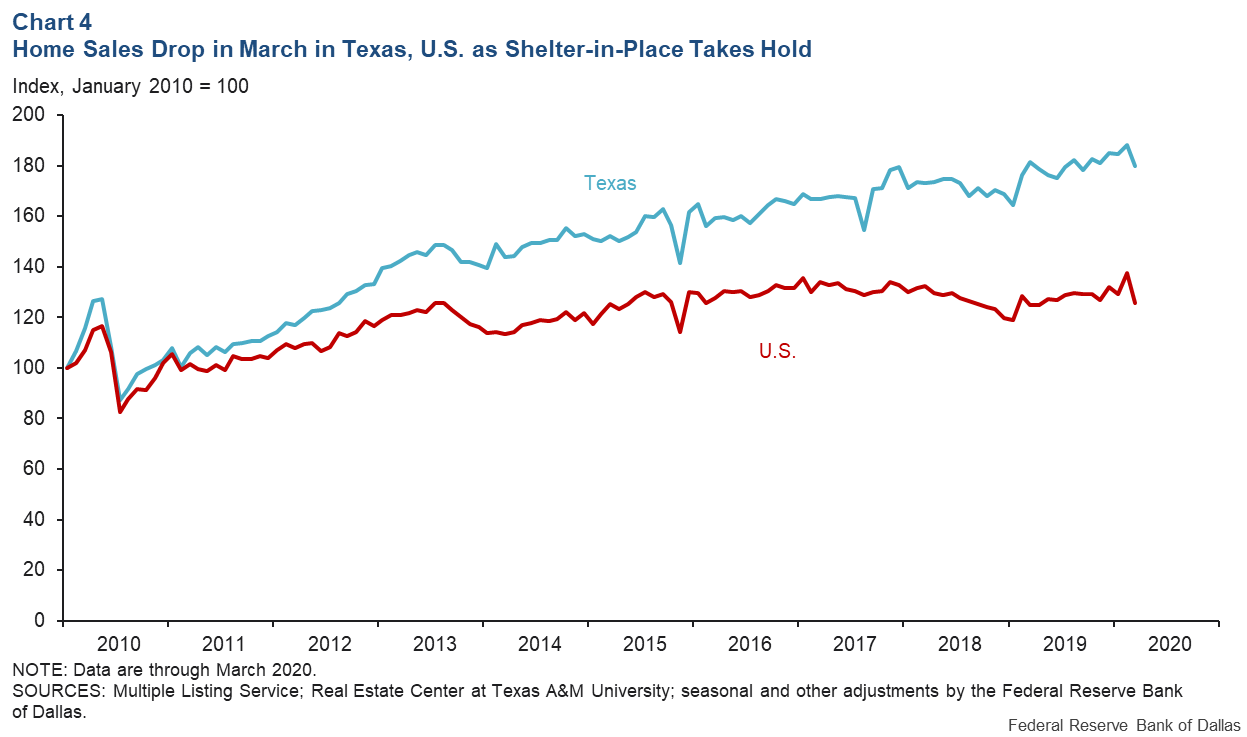

The impact of COVID-19 is beginning to weigh on construction and real estate activity. Texas existing-home sales fell 4.5 percent in March, the biggest drop since January 2018, though less-pronounced than the 8.5 percent U.S. decline (Chart 4). The difference was likely due to the timing of shelter-in-place mandates, issued later in Texas than in several other large states.

Pending home sales—a forward-looking measure of properties under contract but not yet closed—dipped relative to February and year-ago levels. Listings dropped sharply year-over-year in March as sellers either took their homes off the market or preferred to wait to list their homes until conditions improve.

Home listings typically rise in early spring, which marks the beginning of the homebuying season. Anecdotal reports suggest that new-home sales were beginning to gradually improve in mid- to late-April from low levels, but overall, sales are expected to remain weak in the near term despite historically low mortgage rates. The 30-year fixed mortgage rate dipped to an all-time low of 3.23 percent (average) for the week ended April 30, according to a Freddie Mac series that dates back to 1971. In mid-March, the comparable mortgage rate was 3.65 percent.

Texas apartment markets appear to be faring slightly better than those elsewhere in the U.S. April rent collections in all major Texas metros exceeded the national figure as of April 26, according to data from the National Multifamily Housing Council and RealPage, a property management software firm.

New leasing activity appeared to be slowly picking up and was higher relative to last year during the week ended April 25. The exception was Austin, probably due its large student-tenant population. Overall demand this summer will likely be subdued relative to last year. Given recent mass layoffs and moratoriums on evictions, there is trepidation about the prospects for rent collections in May.

Weakening commercial space outlook

Texas construction contract values plunged 13.9 percent in March, similar to the U.S. decline (16.3 percent). Construction activity remained elevated in March, but contacts reported that projects were being canceled or temporarily halted during April.

Office demand softened in Dallas–Fort Worth and Houston in the first quarter, with the pandemic likely affecting leasing activity in the latter part of the quarter. Vacancy rates rose in Austin and San Antonio along with DFW and Houston. Office activity is expected to be restrained, particularly in Houston, where energy companies account for a considerable share of occupied office space. Conditions in Houston’s office market were weak prior to COVID-19, a hangover from the 2015–16 energy bust.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.