Commodity financing markets shaken by Russia invasion; monitoring for U.S. financial stress

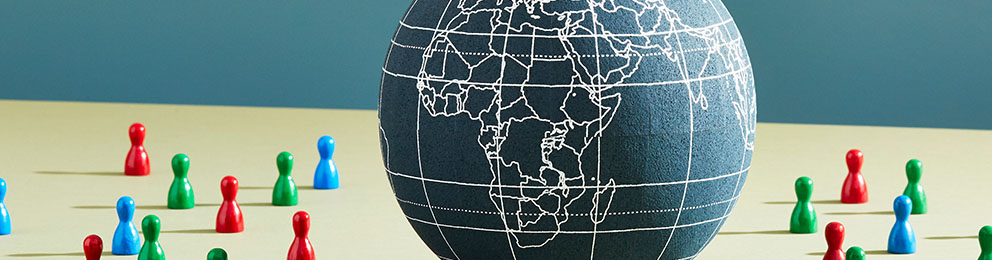

Since Russia invaded Ukraine Feb. 24, the prices of a range of commodities, including energy, foods and metals, have experienced some of the largest increases since the 1970s. These price movements have been exceptional in both their size and speed.

The movements have also been notable for the breadth of the shock across different commodities. While volatility in commodity markets is not unusual, rapid and correlated price increases across many different types of commodities at once is much rarer.

In addition to the Ukraine invasion, these movements coincide with international sanctions on Russia and have placed pressure on financial sector intermediation in global commodity markets.

Recent evidence of risk management weaknesses at the London Metals Exchange—the lack of monitoring of large positions, suspension of trading and the reported strains on multiple clearing members in nickel trading—is another concern.

Ongoing developments in commodities should be monitored for potential impacts on financial conditions broadly.

Commodity prices and intermediation: potential for a negative feedback loop?

Key participants in commodities markets include producers, commodity trading firms and banks. Some entities play more than one role—for example, Glencore PLC, the world’s largest commodity trading firm, is also a major producer of several commodities.

While high commodity prices generally boost profitability for commodity producers and trading firms, when prices abruptly increase, firms that rely on bank credit must seek more in order to finance the commodities that they store, ship, trade and/or process.

Additionally, entities involved in trading and producing commodities often hedge their exposures using derivatives markets—mostly with futures and options—to protect themselves against unexpected or extreme price swings. Traders and producers are typically required to do so by covenants in their bank loans to reduce default risk.

Derivative hedges for firms that are long the underlying commodities are typically known as offsetting “short” positions—that is, the derivative position protects against a commodity price decline. These hedges, however, have liquidity implications for firms using them.

Specifically, while the two positions net out in an economic sense, the cash flows aren’t offsetting. For example, a commodity trading firm may buy a physical commodity and then also expend cash on a derivative hedge against falling prices. However, if commodity prices rise, the derivative position taken to guard against a price decline loses money. Margin calls from the derivative counterparty may follow, requiring that the trader/producer provide additional funding of the hedge and further draining cash.

More broadly, the financing needs for global commodities increase significantly as prices surge. When prices of commodities rise quickly, not only do the prices of goods rise, but also the associated price volatility increases the size of margin calls (Chart 1). The rapid price increases across a range of commodities means that trading firms need additional credit to finance not only the goods they purchase, but also the margin they must post.

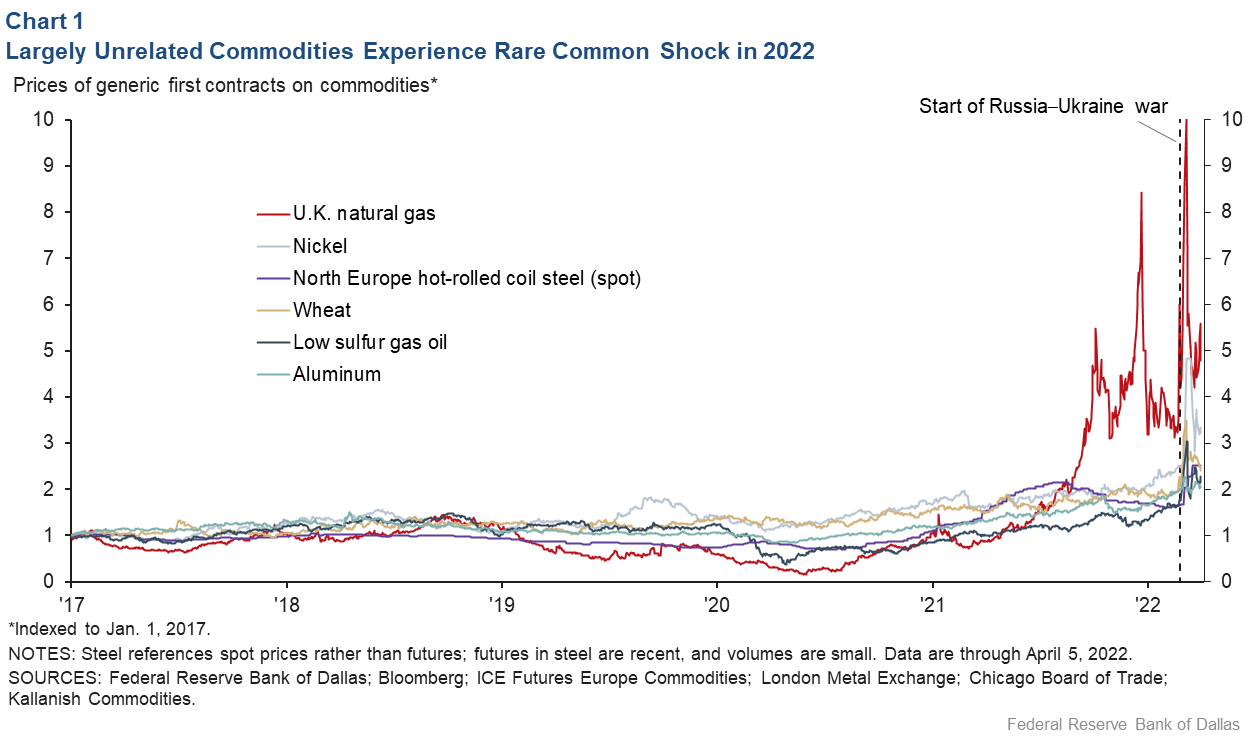

The liquidity strains associated with margin calls for hedges can incentivize firms to trade further in derivatives. To protect against further commodity price surges, firms may buy commodities options with higher strike prices—the price at which an option can be exercised—to generate cash inflows that offset margin calls on their short commodity futures positions.

For example, while some of the growth in out-of-the-money options on oil may reflect market views about the future path of prices, some of this activity may also come from firms seeking to minimize the liquidity strains associated with other derivative positions (Chart 2). In essence, the firm that normally seeks to position itself against a loss also takes the opposite position (to limit gains) in order to reduce potential cash flow strains associated with its hedging activity.

In this environment of growing commodity financing needs, banks are the main source of credit to commodity trading firms. There are some reports of banks paring back and being unwilling to increase their exposures to these firms. While so far, commodity trading firms appear to have obtained the credit necessary to continue their intermediation activities, the recent situation highlights some vulnerabilities.

A pullback in credit to a few commodity trading firms could leave remaining ones unable to meet demand for commodity intermediation, potentially creating a negative feedback loop that causes commodity prices to rise further.

How international sanctions on Russia affect global commodity financing

International sanctions on Russian entities complicate global commodity market financing markets in two ways. First, banks may be reluctant to provide financing to commodity trading firms involved in acquiring, storing or distributing Russian commodities. This may be due to the extensive sanctions, the potential for sanctions to expand because of reported atrocities against civilians or a further escalation in Russia’s war against Ukraine and the reputational risk associated with this intermediation. Commodity firms may also decide to self-sanction their activities involving Russian commodities

To be clear, the intent of international sanctions is to negatively affect intermediation to the Russian economy and, in turn, stop the conflict in Ukraine.

Second, there is the risk international sanctions could expand to include foreign subsidiaries of Russian state-owned commodity producers (such as Gazprom’s U.K. domiciled trading subsidiary or integrated oil company Rosneft’s subsidiaries), which are active in selling, trading or distributing commodities outside of Russia.

Like commodity trading firms, these companies can be active in both physical and derivative commodity markets. Their inability (or even unwillingness) to meet physical delivery or derivative obligations could leave non-Russian counterparties, including European utilities and refineries, with losses.

Such a situation could manifest in the European utility sector in ways akin to what happened to some electricity producers during the February 2021 freeze in Texas. Some Texas electricity providers were forced to make expensive purchases in the spot market for natural gas used in power generation or were unable to produce and deliver electricity that they had sold forward in the derivatives market. (These risks may provide some context for a recent German government decision to take control of a local Gazprom subsidiary.)

U.S. monitoring of global commodity market intermediation

Monitoring developments in the intermediation of commodity markets is key for at least three reasons:

- First, price or counterparty shocks could trigger a negative feedback loop that causes commodity prices to rise further. Additional commodity price increases exacerbated by financial stresses could result in demand destruction while elevating realized and expected inflation.

- Second, a further sharp rise in global commodity prices due to intermediation challenges could weigh heavily on risk assets and increase volatility, leading to an abrupt and significant tightening in financial conditions.

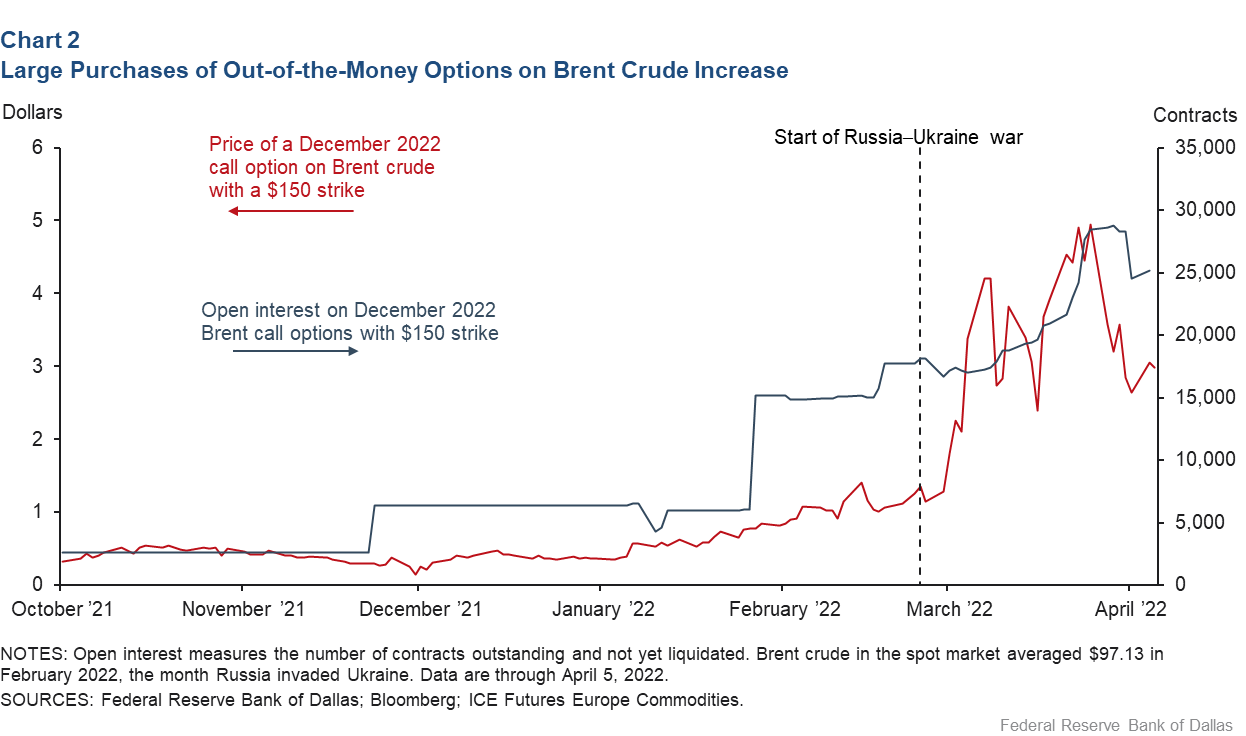

- Finally, because commodities are largely settled in U.S. dollars, firms are dependent on U.S. and foreign banks for dollar-financing to fund both their physical purchases of commodities and the associated derivative hedge positions. Since foreign banks’ commodity financing is often U.S. dollar-denominated, disruptions in commodity financing can weigh on offshore dollar liquidity (Chart 3).

In response to stresses to date, a European energy trade group has called for European central bank-backed facilities that could provide emergency liquidity to energy markets. Should a further commodity price shock occur, correlations between commodity prices and offshore dollar funding costs could once again increase. That said, the threshold for central bank intervention in unregulated markets is high; it would be prudent for firms active in commodities markets to proactively assess and further strengthen their liquidity profiles.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.