Domestic banks are inelastic providers of marginal funding to repo markets

While many types of entities are active in U.S. repo markets, the marginal supplier of liquidity to repo markets to meet unmet demand for leveraged financing differs based on how plentiful liquidity is overall and, by extension, rates of return for lenders. The time of day that lenders know how much excess liquidity they have on-hand varies by institution type, which makes some more able to elastically meet demand than others.

Repo markets clear very early in the liquidity day, which is significant for the elasticity of marginal bank lending into repo, defined here as the sensitivity of unplanned additional lending to changes in rates. As of 2021, 64 percent of cleared repo volume traded by 8:30 a.m. each day and about three quarters of tri-party repo volume had traded by 9 a.m., after which trading slowed. Anecdotally, activity has continued to shift earlier since then, with a larger share of volume occurring by 9 a.m. This timing is driven by borrowers’ liquidity needs and structural factors, particularly a desire to avoid daylight overdraft charges. Because this repo market timing would drain their reserve balances in advance of other intraday liquidity and payment demands on their reserve balances, banks are not well-suited to be marginal lenders in repo.

Domestic banks are not the first marginal liquidity supplier as reserves decline

As reserves fall and money market rates rise, the first marginal source of liquidity is money market funds that would otherwise lend into the New York Fed’s overnight reverse repo operation (ON RRP). As non-bank financial institutions, money funds do not have master accounts at the Federal Reserve, so they do not earn interest on reserves, but they have access to the ON RRP as an alternative investment option. The ON RRP offering rate is currently set 15 basis points below interest on reserves (IORB) within the Fed’s target range, making money funds the first marginal liquidity supplier as rates increase.

- Bottom of the fed funds target range: Overnight reverse repo.

- 15 basis points above the bottom of the target range: Interest on reserves.

- Top of the target range: Standing repo operations and discount window.

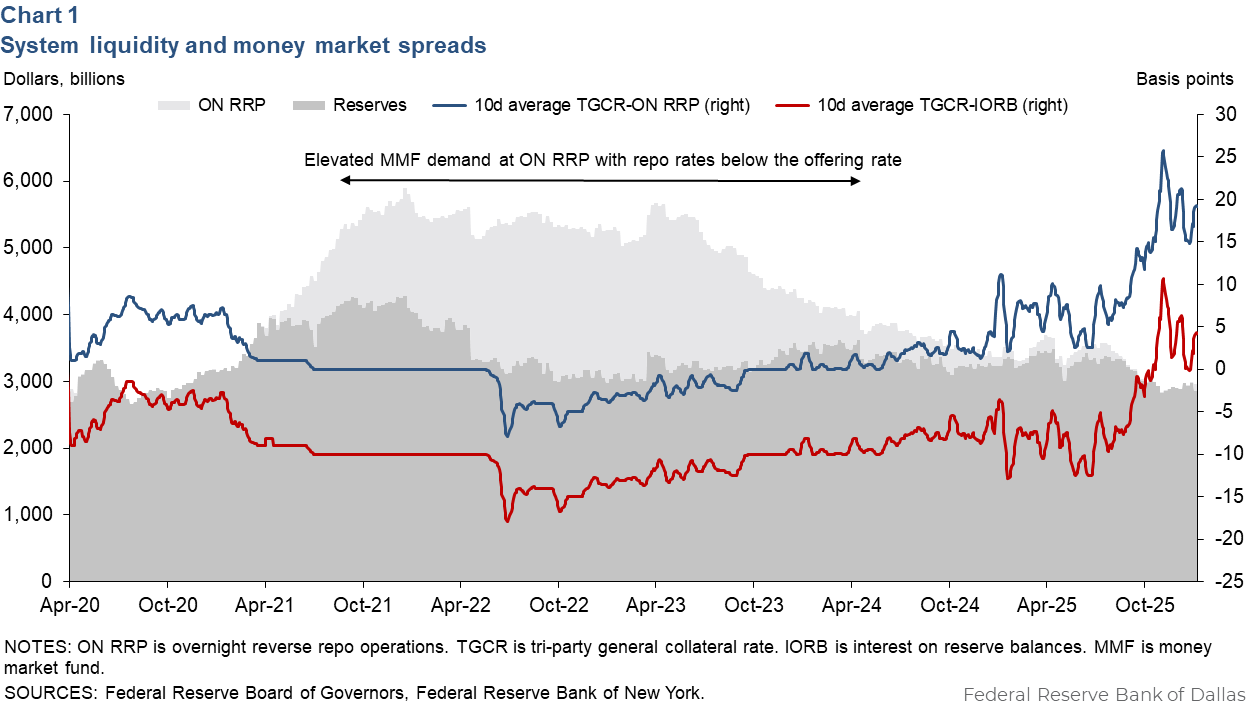

When general collateral repo rates are at or below the ON RRP rate, the value of relationships with dealers causes money funds to offer them first right of refusal to funding and park any excess at the ON RRP (Chart 1). This drove a rapid increase in ON RRP participation in 2021 as repo rates were pinned at the operation’s offering rate. Unlike other money market participants, money funds’ liquidity needs are relatively predictable and are generally known by around 11 a.m. ET. This, along with the relationship component, makes money funds a very elastic source of liquidity; money fund repo lending is highly sensitive to changes in repo rates as they move from one side of the ON RRP offering rate to the other.

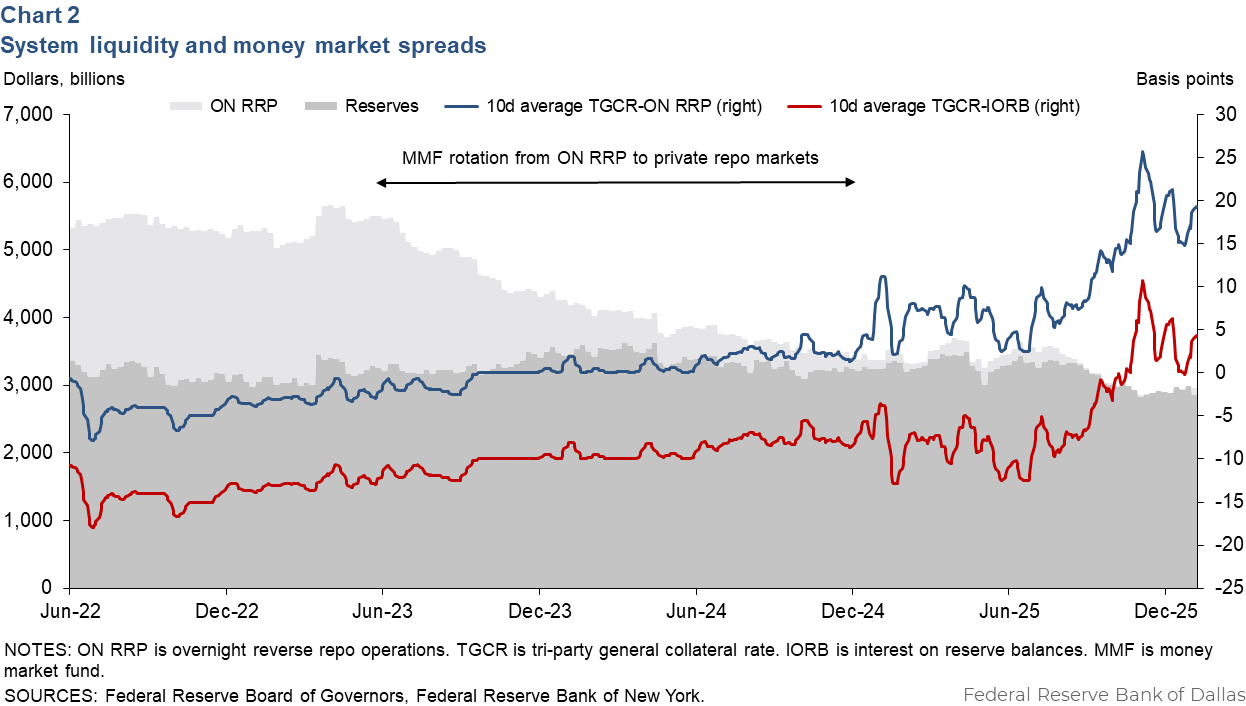

As money market conditions shift amid declining liquidity, a dealer that offers a money fund a rate at least equal to the ON RRP offering rate during the morning session will be successful in drawing marginal liquidity away from the ON RRP into private repo markets (Chart 2). Money funds that have excess cash can lend into repo through the majority of the trading session if rates are attractive, then place any excess cash with the Fed at the ON RRP, which takes place from 12:45 p.m. to 1:15 p.m. ET. Participation in the ON RRP began to decline in 2023 as repo rates moved higher.

As reserves continue to decline, the next marginal provider of liquidity is FHLBs, which would otherwise lend in federal funds, typically to foreign banking organizations (FBOs) that are engaging in IORB arbitrage. Unlike money funds, FHLBs have liquidity needs that span beyond a morning redemption window. As a result, they generally need to hold some amount of liquidity that is demandable or early return, and that portion is invested in fed funds or interest-bearing deposit accounts. The rest is not expected to be needed on a given day and thus can be lent into repo early if prices are relatively attractive or into fed funds if they’re not.

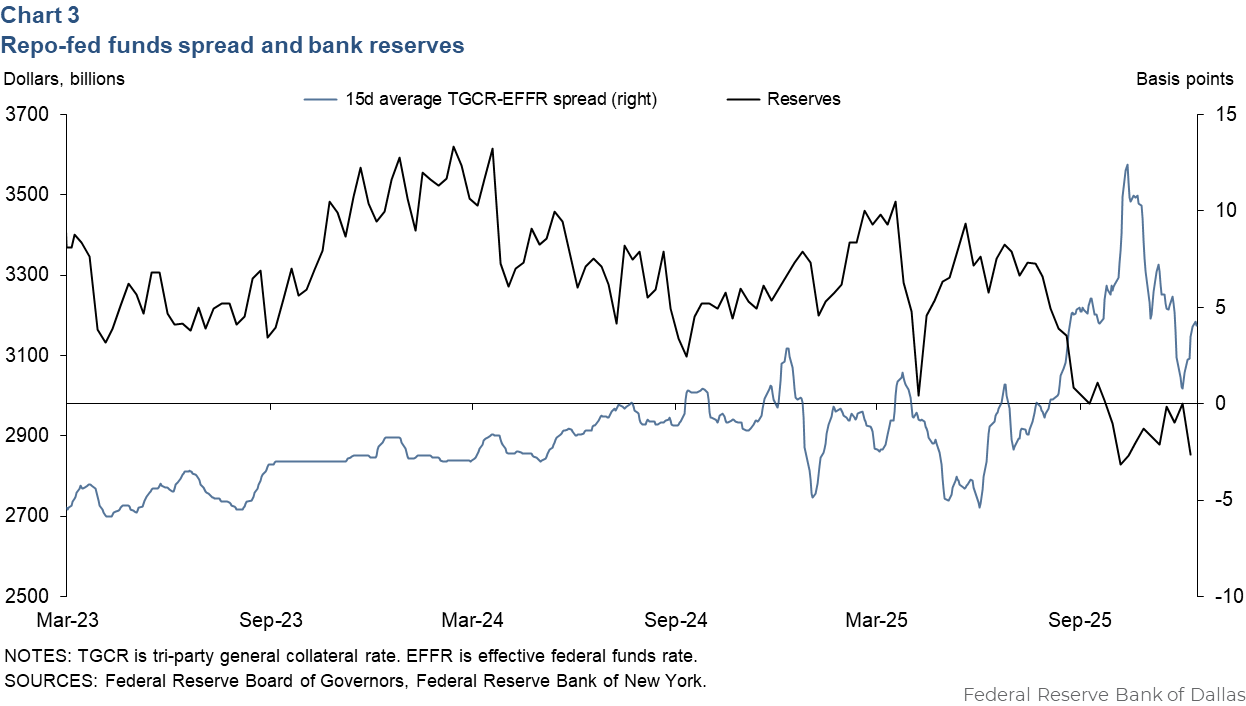

This substitution by FHLBs between lending to FBOs in federal funds and lending into repo becomes another marginal source of liquidity to repo markets when money market rates rise persistently above the ON RRP rate but remain below the rate of interest on reserves (Chart 3). When liquidity is abundant, repo rates tend to remain below federal funds. As money market rates begin to rise toward IORB, repo rates move first. When repo rates equal and exceed the federal funds rate, FHLBs shift from lending in federal funds to lending in tri-party repo. This pressures federal funds rates higher, causing IORB arbitrage by FBOs to decline as it becomes less profitable. Chart 3 shows this shift; the tri-party repo rate spread to the federal funds rate rises above zero and causes a decline in reserve holdings due to FBOs exiting IORB arbitrage.

Once this transition is complete, while FHLBs may still engage in repo lending, they no longer act as marginal suppliers by substituting between these markets. Given the much smaller size of the available portion of FHLB liquidity pools in comparison to money funds, this process can occur rapidly.

Repo lending reduces banks’ liquidity before their needs are known

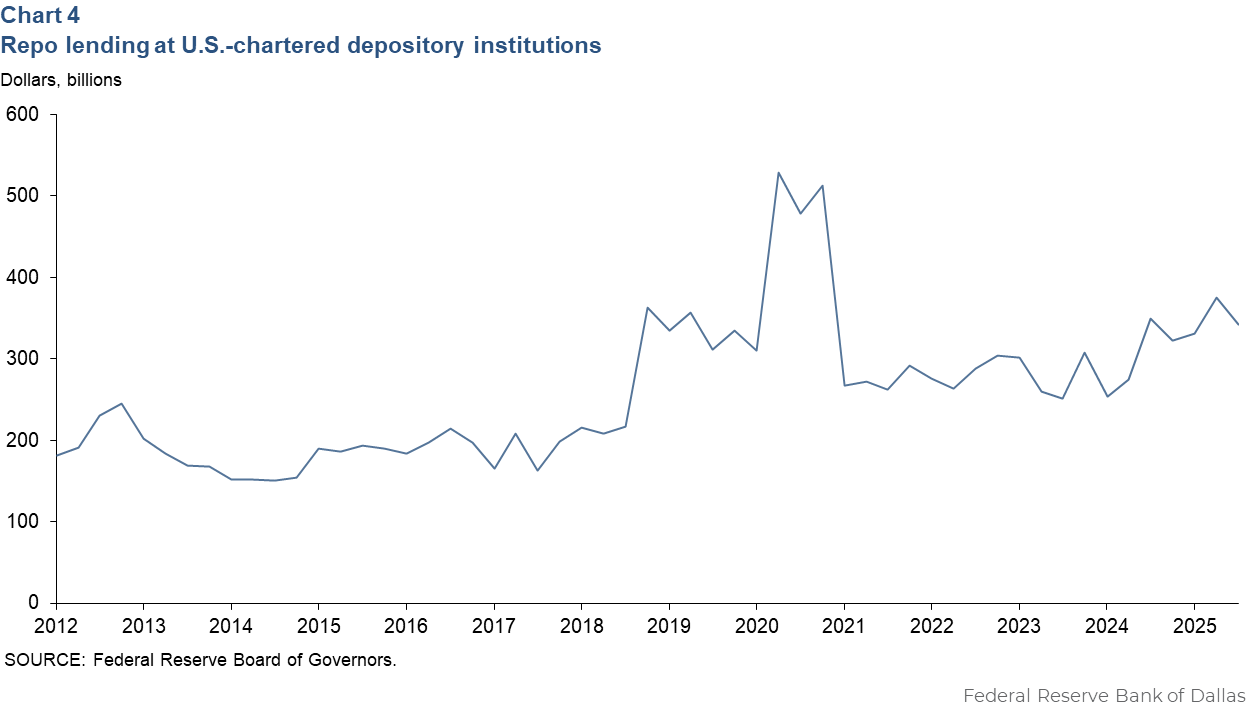

The final pool of marginal liquidity is domestic banks deploying excess reserves, which occurs when repo rates rise to or above IORB. This is a much less elastic pool of liquidity than money funds or FHLBs because, while banks often engage in significant quantities of planned repo lending (Chart 4), marginal additional repo lending in response to high rates is likely to draw on reserves that were intended for other higher-priority needs.

Reserves serve two overlapping purposes. They are simultaneously one of the highest-quality safe assets, one that bears interest, and reserves are also a unique means of settlement. Bank reserve holdings are predominantly a function of regulatory liquidity requirements, intraday payment and settlement needs, and near-term projected outflows. These factors are intertwined and incentivize prioritizing a robust intraday liquidity position.

Delays in intraday payments have been shown to increase when reserves become less ample as banks are highly incentivized to conserve their intraday liquidity. A bank’s view on what portion of their reserves is excess and available for lending could be very different between 7 a.m., when the bulk of repo market trading is occurring, and 4 p.m., when the primary sources of intraday liquidity demands on banks have passed and banks are highly certain as to their reserve needs.

Overnight internal liquidity stress tests (ILSTs) motivate banks to keep sufficient intraday liquidity to avoid incurring daylight overdraft borrowing in a stress event. While modifying ILST requirements may have other benefits, including allowing a more efficient central bank balance sheet through lower steady-state reserve supply, it would not necessarily increase the elasticity of banks’ marginal repo lending over the long run. Banks would likely reduce their steady-state liquidity holdings to their new lower needs, rather than hold an excess that could be lent into repo as money market conditions warrant.

Although repos are interest-bearing safe assets, they cannot be directly used for settlement, unlike reserves. If a bank exchanges reserve holdings for repos, it receives any additional interest income over interest on reserves in exchange for a loss in intraday liquidity. As a result, repo lending, like lending into the foreign exchange (FX) swap market, is a form of reserve draining intermediation. While reserves are conserved in the aggregate, lending into FX swap or repo markets reduces the reserves on hand for an individual institution engaging in those activities.

When money market rates are above the rate of interest on reserves, the opportunity cost of holding reserves is high, incentivizing banks not to hold any more reserves than necessary to meet their own expected liquidity needs, conservatively estimated. Planned and generally stable repo lending volumes are considered in these needs, but generally banks cannot be expected to earn a negative spread to hold extra cash for potential lending into the broad market. As a result, in the precise regime in which banks are the marginal lenders, they are inelastic suppliers of liquidity to repo during morning hours when most trading occurs.

Additionally, given the short tenor of repo transactions, the return is generally not sufficient to persuade a bank to materially lower its reserve holdings. Over the past five years, the largest one-day spike of SOFR over IORB was 32 basis points, which occurred on Oct. 31, 2025. A large repo trade of $100 million dollars, assuming a bank receives a return equal to SOFR, would on this anomalous day yield a return over IORB of 0.32 percent times 1/360 times $100 million, or about $89 thousand—a paltry sum to a global bank.

Statement date volatility highlights the role of day-of liquidity provision

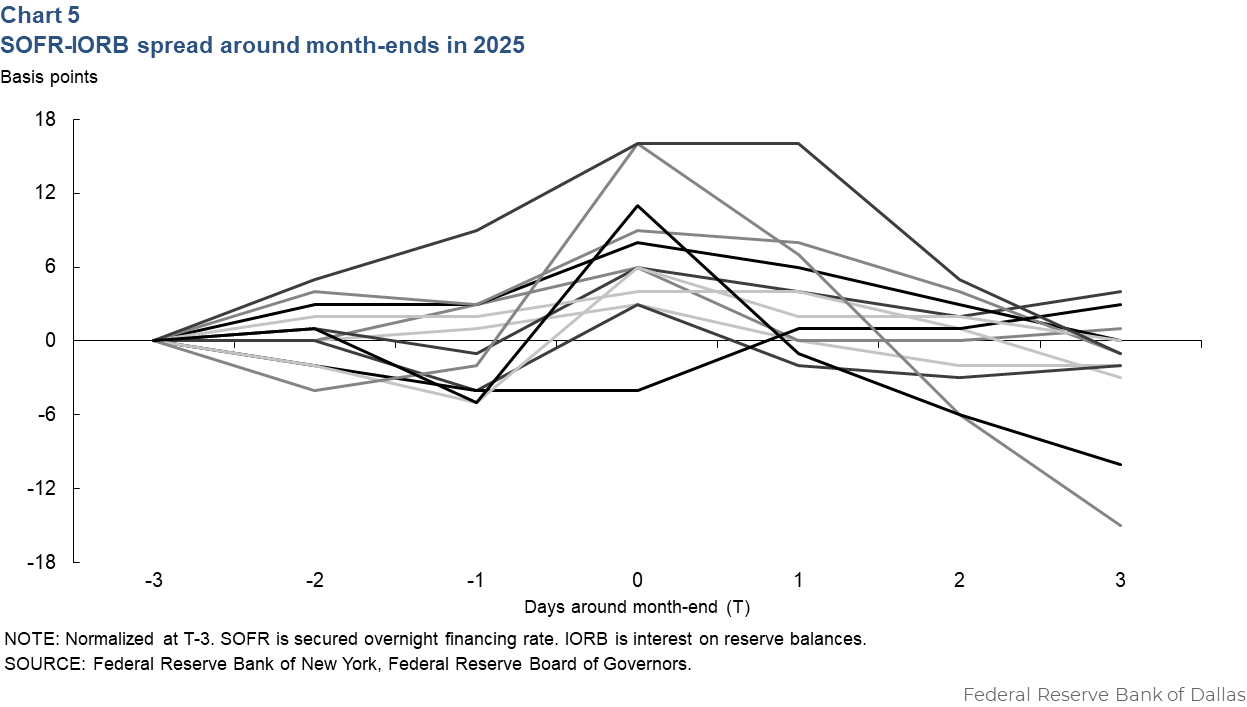

Month-ends, especially quarter-ends and October month-end, which is the Canadian fiscal year-end, often see notable volatility in repo rates (Chart 5). While the well-documented volatility on these statement dates is often treated as idiosyncratic, due to the unusual balance sheet pressures that they involve, they are good illustrations of the limited day-of liquidity provision available from domestic banks.

The increased volatility on statement dates occurs when FBOs pull back from repo intermediation, effectively making domestic banks marginal suppliers of liquidity to repo markets even when marginal liquidity on typical days is provided by other sources. Rates above IORB on statement dates should draw lending from domestic banks, but timing constraints, the importance of reserves for liquidity needs and the meager return limit their appetite.

Market participants have long observed that statement dates following especially volatile episodes in repo tend to exhibit lower volatility. This is attributed to repo borrowers in the levered community securing committed balance sheet from dealers in advance of the statement date, often in the form of term funding covering the period-end turn. When this occurs, the repo lending becomes an asset for a bank, and it is incorporated into the bank’s liquidity planning, sidestepping the constraints that limit day-of lending.

Though observations are largely anecdotal, this phenomenon illustrates how the interaction between unanticipated day-of variations in funding needs and domestic banks’ liquidity constraints drives repo market volatility and can decouple rates in broader funding markets from solely interbank markets.

Intraday timing of repo markets does not encourage flexible bank lending

While domestic banks engage in a substantial amount of aggregate repo lending, they are highly inelastic sources of unplanned day-of liquidity provision to repo markets. Banks are incentivized to prioritize robust intraday liquidity management, which is at odds with the concentration of repo trading in the early morning. The minimal return from overnight repo, even on statement dates, is not a strong motivator for banks to deviate from this approach.

About the authors