More workers find their wages falling even further behind inflation

A rising real wage allows workers to improve their standard of living. However, the Wall Street Journal recently reported that “… vast numbers of Americans find their cost of living is rising faster than the income they’re bringing home.”

How prevalent is this situation and how much is the shortfall? We find that a majority of employed workers’ real (inflation-adjusted) wages have failed to keep up with inflation in the past year. For these workers, the median decline in real wages is a little more than 8.5 percent. Taken together, these outcomes appear to be the most severe faced by employed workers over the past 25 years.

Economic recovery and rising inflation

Inflation picked up dramatically over the past year as the economy continued to recover from COVID-19’s initial impact in first quarter 2020. At the same time, tight labor markets are generating stronger wage growth for many workers. An important question is whether stronger wage growth is keeping up with higher inflation. The answer will determine how many workers are experiencing rising or falling real wages.

We examine the behavior of real wages using Current Population Survey data to measure individual wage growth over 12 months. However, we cannot follow individuals who change residence over the period. In addition, we cannot follow individuals for periods longer than a year, so the mix of people surveyed constantly changes.

Individuals who work by the hour report their wages, while for salaried workers, we impute wages from their reported earnings and hours. The most recent data allow us to calculate individual wage growth from second quarter 2021 to second quarter 2022.

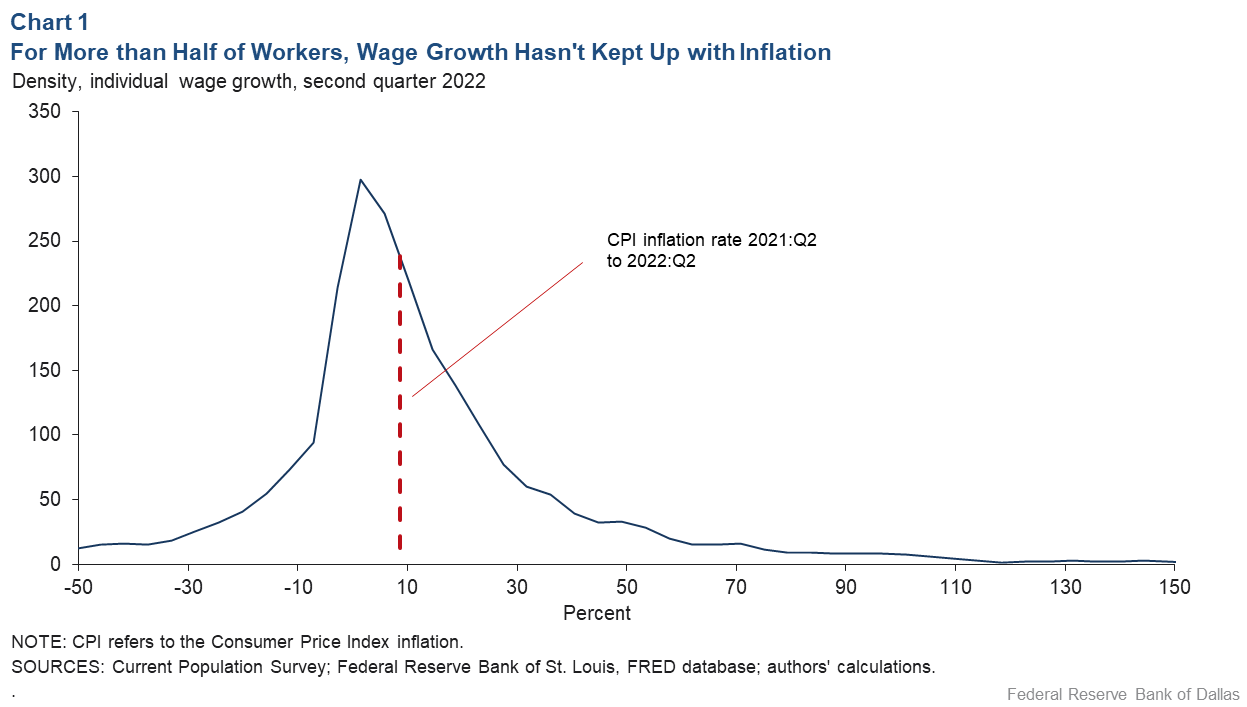

Chart 1 shows the distribution of wage growth for this period. The first thing to note is the wide range of wage movements. Over the 12-month period, some workers more than doubled their wages, while others suffered wage cuts.

The dashed vertical line indicates the CPI inflation rate of 8.6 percent during the period (based on CPI-U, all urban consumers). All individuals to the left of the dashed line experienced wage growth that was less than the CPI inflation rate, although we recognize that an individual’s personal inflation rate is the appropriate comparison point. Consequently, these people―53.4 percent of all workers―experienced real wage declines.

How frequently do workers experience real wage declines?

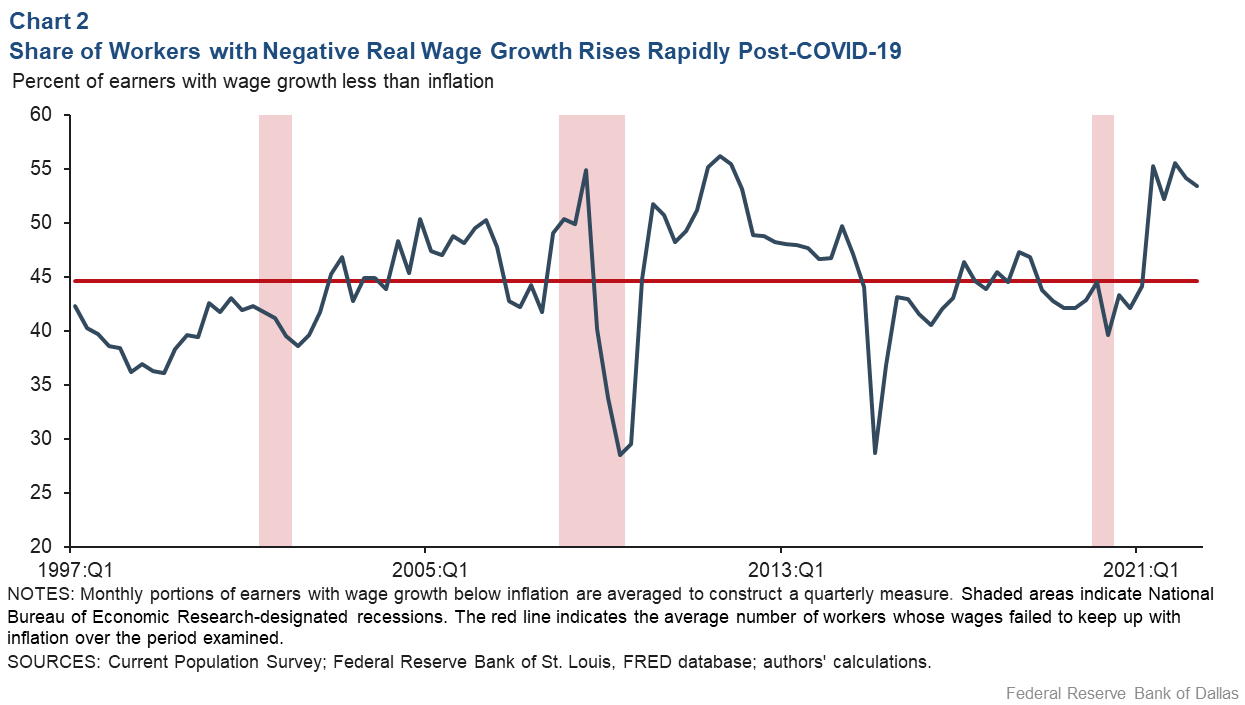

How typical is it for a majority of workers to experience falling real wages? To answer this, we repeat our exercise going back to the mid-1990s. Chart 2 shows the fraction of workers whose nominal wage growth was less than the inflation rate over the preceding 12 months.

Because we cannot follow individuals for longer than a year, our analysis does not allow us to say anything about the nature of real wage growth over workers’ careers. Over the past 25 years, on average, 44.6 percent of surveyed workers experienced negative real wage growth over the prior 12 months.

There is, however, variation in the inability of wage growth to keep pace with inflation, with the fraction of workers experiencing real wage declines typically in the range of 42 to 48 percent.

In the post-COVID-19 recovery, the share of individuals with negative real wage growth rose sharply and reached 55.5 percent before falling back to the current 53.4 percent. The last time the percentage was this high was in 2011.

The chart also shows two downward spikes in the incidence of negative real wage growth during the Great Recession and in 2015. The spikes were a consequence of inflation briefly turning negative during those periods. Specifically, the most frequent response for individual wage growth from Current Population Survey data is zero percent. When inflation turns negative, this large group of individuals switches from displaying negative to positive real wage growth, decreasing the incidence of real wage declines.

Gauging the severity of failing to keep up

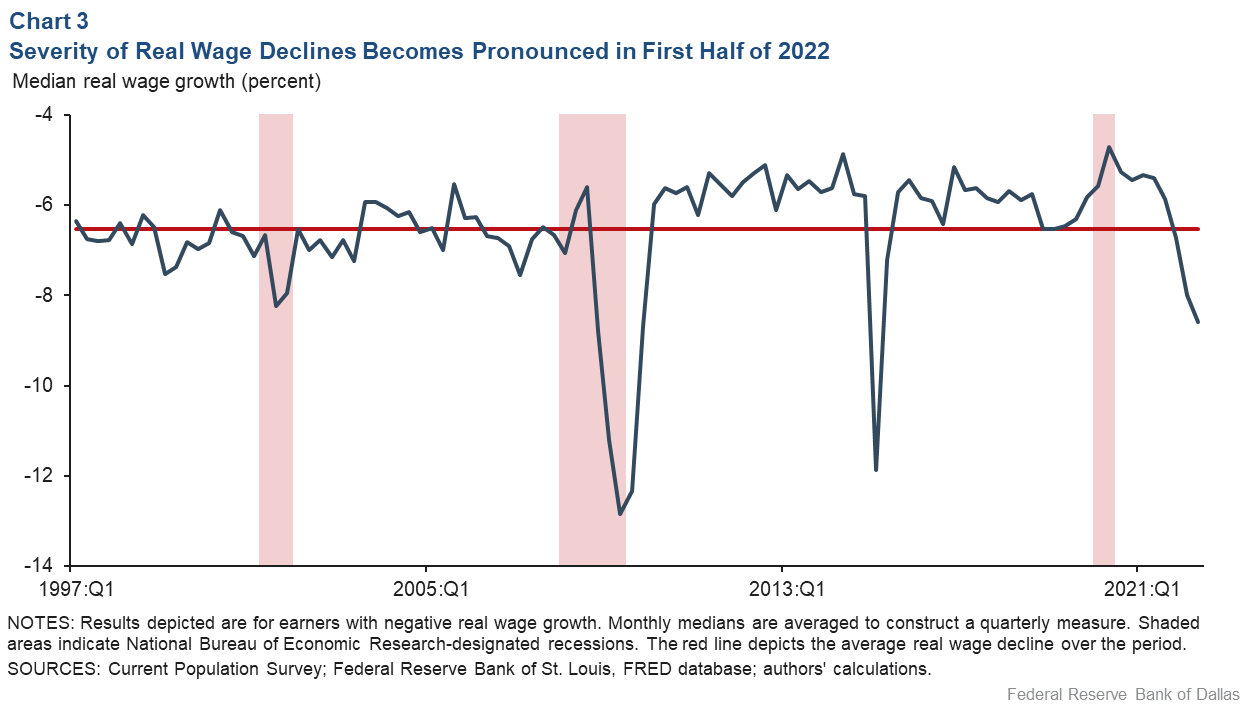

How severe are the losses for workers experiencing negative real wage growth? For the 53.4 percent of such workers in second quarter 2022, the median decline (that is, half of the declines were larger and half smaller) in real wage growth was 8.6 percent.

How does the severity of the real wage decline in second quarter 2022 compare with the declines over the last 25 years? The average median decline over the last 25 years is 6.5 percent, with real wage declines typically falling in the range of 5.7 to 6.8 percent (Chart 3).

While the chart shows two declines that are more severe than in second quarter 2022, these spikes occurred during the Great Recession and in 2015 and, again, result from inflation turning briefly negative.

Technically, negative inflation readings move the large number of individuals with zero nominal wage growth out of the negative real-wage-growth category, which raises the conditional severity. However, these two episodes contrast with the current period in which the increase in the incidence and severity of negative real wage growth is associated with elevated inflation.Unparalleled period of declining real wages

Despite the stronger wage growth due to the tightness of the labor market, a majority of workers are finding their wages falling even further behind inflation. For workers who experienced a decline in their real wage in second quarter 2022, the median decline was 8.6 percent.

While the past 25 years have witnessed episodes that show either a greater incidence or larger magnitude of real wage declines, the current time period is unparalleled in terms of the challenge employed workers face.

About the Authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.