Utility-scale solar shines in Texas despite tariffs, federal policy changes

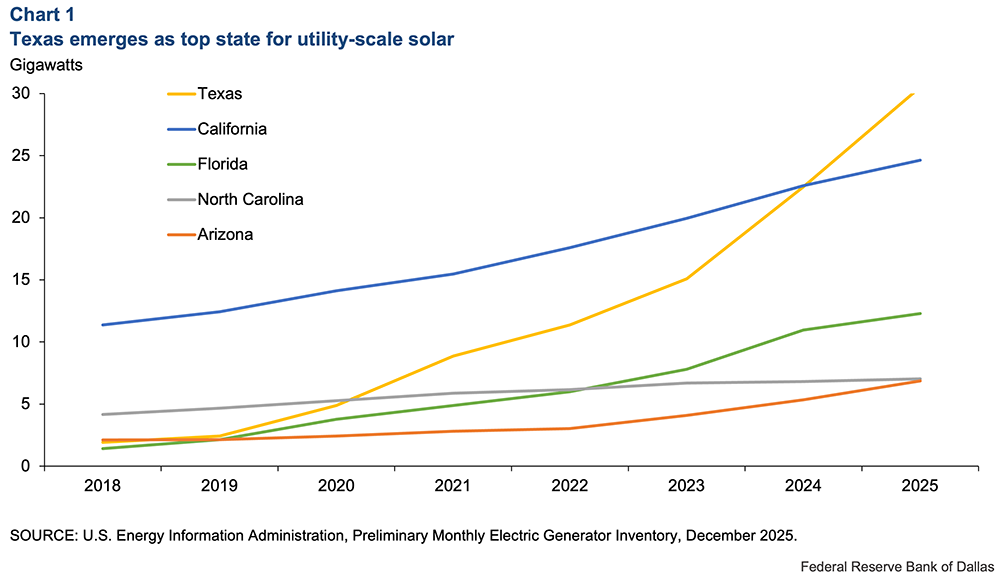

Texas is now the top state for utility-scale solar power generation capacity. However, developers of new solar projects face a changing operating environment, one lacking strong federal policy support but also featuring cost-boosting tariffs on imported solar cells and modules.

Despite these challenges, Texas managed to add just as much solar capacity in 2025 as it did in 2024, although many other states experienced a slowdown (Chart 1).

Looking forward, Texas will likely experience strong growth in power demand, with an increasing number of power-hungry data centers and other sources of new demand. A persistent slowdown in new solar capacity could make satisfying that growth more difficult.

Economics, tax incentives boost solar adoption

The economics of installing solar generation significantly improved in the 2010s, driven by larger module size, greater efficiency and economies of scale reducing the cost of modules on a dollar-per-watt basis. This increased investor interest in solar relative to other forms of generating capacity, such as coal, nuclear and natural gas.

Texas, relative to other regions, benefits from factors that improve solar power’s economics, notably many hours of clear, sunny skies bringing high levels of solar irradiance.

Solar adoption also benefited from federal tax credits. A 10 percent investment tax credit was enacted in 1978. The credit expanded to 30 percent under the Energy Policy Act of 2005. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act extended this credit through 2032. (A production tax credit is also available, although solar project developers generally favor the investment tax credit).

Solar operating environment shifts dramatically in 2025

Against this backdrop, solar developers nationwide encountered a variety of challenges in 2025. These include a much less supportive federal policy environment, heightened trade uncertainty and substantial tariffs on important components used in solar systems.

New projects coming online after 2027 will no longer qualify for Inflation Reduction Act tax credits under terms of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act signed into law in July. While there are some exceptions, that change will largely make utility-scale solar development less economical.

Permitting has become more challenging on federal lands for renewable projects. And starting in 2026, new projects must also satisfy certain sourcing requirements for equipment and materials to qualify for tax credits.

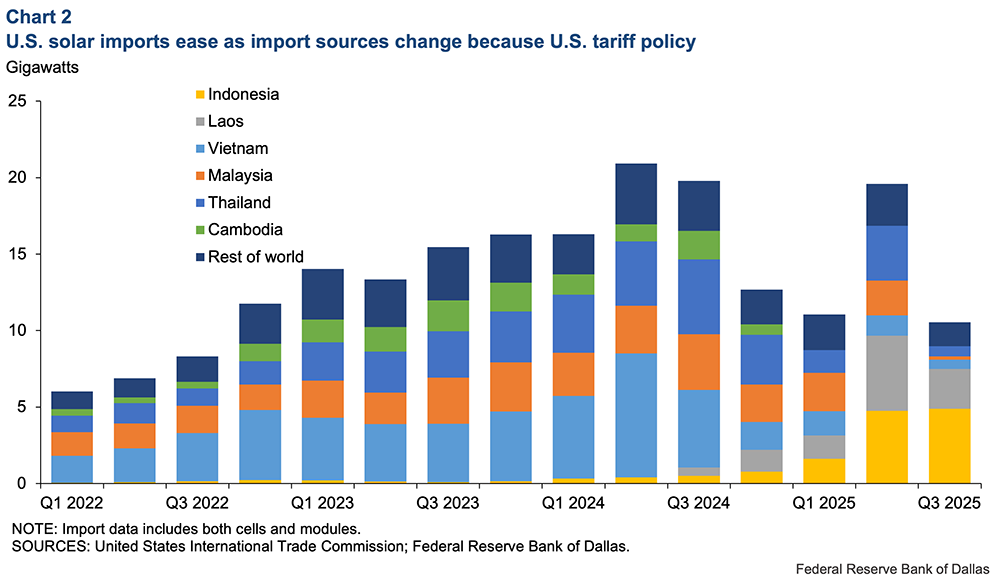

Additionally, many solar projects use imported solar panels, typically from Asia. Solar panels from China have been subject since 2018 to Section 201 tariffs (designed to blunt a danger to domestic U.S. industry) and Section 301 tariffs (involving unfair technology transfer). The measures led to an import shift toward Southeast Asia countries.

Relief was short-lived, as Southeast Asia panels became subject not only to tariffs but also to antidumping and countervailing duties in 2024. Companies have attempted to mitigate those impacts by stockpiling panels in advance of the trade cost increases and shifting imports to non-tariffed countries.

Imports fell sharply in fourth quarter 2024 and have only partially recovered, according to U.S. International Trade Commission data (Chart 2). Recently, imports have shifted from Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia (now impacted by solar-specific tariffs) to Indonesia and Laos (generally unaffected by solar-specific tariffs). However, the U.S. International Trade Commission is now probing business practices of companies that export solar panel from Indonesia and Laos, leading to uncertainty about their future status.

Solar additions to continue in Texas despite weaker economics

The new operating environment means weaker economics for solar projects nationwide. Many market analysts have lowered their expectations for how much solar power will be added in the U.S. in the future.

Despite this diminished outlook, utility-scale solar will remain an important source of new capacity in Texas. Demand for power is expected to increase over the next five years (and perhaps beyond) because of demand from data centers, cryptomining, oil field electrification and new industrial customers.

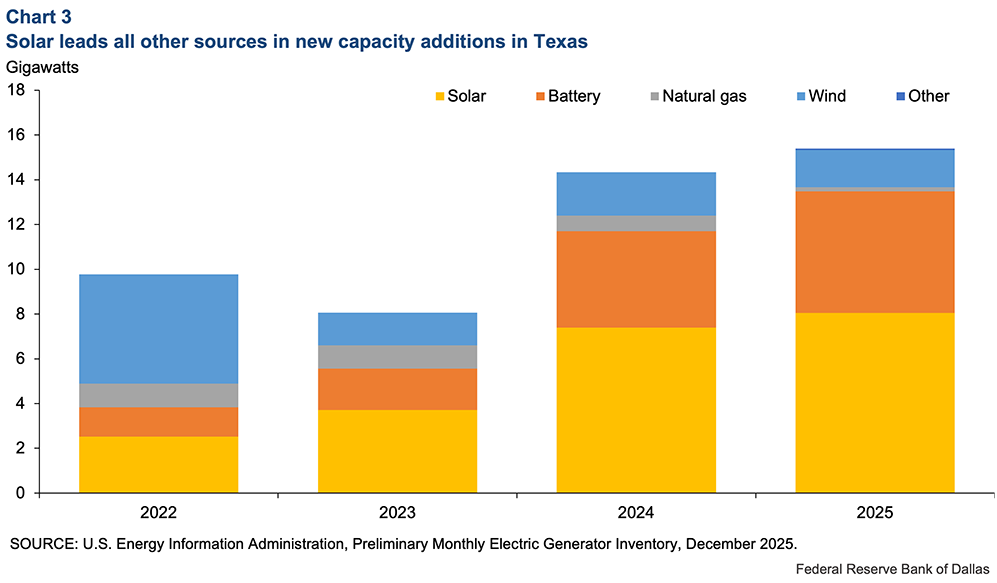

Many alternatives to solar power face their own challenges and constraints, especially in the near future. For example, recent shifts in federal tax incentives have also negatively affected wind power, which in recent years was eclipsed in terms of capacity additions by solar (Chart 3). Nuclear power is experiencing a revival of interest but requires long lead times to bring new capacity online.

Natural gas, abundant in the region, can provide reliable all-day baseload power, unlike solar power. However, the price of new natural gas turbines for power plants has increased considerably in recent years. Orders are also backlogged, limiting how much capacity can be added in the aggregate in the near term.

Reflecting this environment, Texas is anticipated to add substantially more solar capacity than other forms of power in 2026, based on data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s monthly survey of generation capacity.

Power-hungry data centers interested in solar

Private companies are not passive actors and may influence how much solar gets added. Hyperscalers behind some of the largest data centers have already shown a willingness to pay for power via power purchase agreements. Under these long-term contracts, a customer agrees to pay a specified price for power from a particular generator.

This is known as a bring-your-own-capacity setup, which offers the potential of speeding up regulatory approval. Although in many cases a power customer does not actually source its power directly from the generator with whom it has the power purchase agreement, the contract provides clarity about future revenue for the power provider, helping many projects get financing and reach completion.

In recent years, the majority of power purchase agreements signed by hyperscalers have been for solar power. Hyperscalers use them to meet sustainability targets, which remain important for many of these companies. Future power purchase agreement prices may increase, reflecting diminishing federal tax credits and mounting tariff costs.

Alternatively, if generation capacity additions fail to keep up with demand, and data centers are unable to interconnect, they may choose to locate some facilities outside of Texas. The state is generally considered the No. 2 destination for data centers behind Virginia. However, other states such as Ohio and Georgia are emerging hotspots.

Relatively flexible interconnection standards, ease of doing business and geographical advantages combined with solar energy project economics will help maintain solar as part of the energy mix and an important driver of data center development in Texas.